Orphan Train Movement

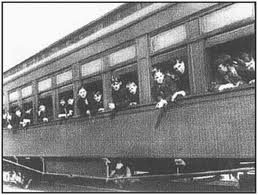

The Orphan Train Movement was a supervised welfare program that transported children from crowded Eastern cities of the United States to foster homes located largely in rural areas of the Midwest. The orphan trains operated between 1854 and 1929, relocating about 200,000 children.[1] The co-founders of the Orphan Train movement claimed that these children were orphaned, abandoned, abused, or homeless, but this was not always true. They were mostly the children of new immigrants and the children of the poor and destitute families living in these cities.[citation needed] Criticisms of the program include ineffective screening of caretakers, insufficient follow-ups on placements, and that many children were used as strictly slave farm labor.[citation needed]

Three charitable institutions, Children’s Village (founded 1851 by 24 philanthropists),[2] the Children’s Aid Society (established 1853 by Charles Loring Brace) and later, New York Foundling Hospital, endeavored to help these children. The institutions were supported by wealthy donors and operated by professional staff. The three institutions developed a program that placed homeless, orphaned, and abandoned city children, who numbered an estimated 30,000 in New York City alone in the 1850s, in foster homes throughout the country. The children were transported to their new homes on trains that were labeled “orphan trains” or “baby trains”. This relocation of children ended in 1930 due to decreased need for farm labor in the Midwest.[3]

Background

The first orphanage in the United States was reportedly established in 1729 in Natchez, MS,[1] but institutional orphanages were uncommon before the early 19th century. Relatives or neighbors usually raised children who had lost their parents. Arrangements were informal and rarely involved courts.[1]

Around 1830, the number of homeless children in large Eastern cities such as New York City exploded. In 1850, there were an estimated 10,000 to 30,000 homeless children in New York City. At the time, New York City’s population was only 500,000.[1] Some children were orphaned when their parents died in epidemics of typhoid, yellow fever or the flu.[1] Others were abandoned due to poverty, illness, or addiction.[1] Many children sold matches, rags, or newspapers to survive.[4] For protection against street violence, they banded together and formed gangs.[4]

In 1853, a young minister named Charles Loring Brace became concerned with the plight of street children (often known as “street Arabs”).[4] He founded the Children’s Aid Society.[4] During its first year the Children’s Aid Society primarily offered boys religious guidance and vocational and academic instruction. Eventually, the society established the nation’s first runaway shelter, the Newsboys’ Lodging House, where vagrant boys received inexpensive room and board and basic education. Brace and his colleagues attempted to find jobs and homes for individual children, but they soon became overwhelmed by the numbers needing placement. Brace hit on the idea of sending groups of children to rural areas for adoption.[5]

Brace believed that street children would have better lives if they left the poverty and debauchery of their lives in New York City and were instead raised by morally upright farm families.[6] Recognizing the need for labor in the expanding farm country, Brace believed that farmers would welcome homeless children, take them into their homes and treat them as their own. His program would turn out to be a forerunner of modern foster care.[4]

After a year of dispatching children individually to farms in nearby Connecticut, Pennsylvania and rural New York, the Children’s Aid Society mounted its first large-scale expedition to the Midwest in September 1854.[7]

The term “Orphan Train”

The phrase “orphan train” was first used in 1854 to describe the transportation of children from their home area via the railroad.[8] However, the term “Orphan Train” was not widely used until long after the Orphan Train program had ended.[5]

The Children’s Aid Society referred to its relevant division first as the Emigration Department, then as the Home-Finding Department, and finally, as the Department of Foster Care.[5] Later, the New York Foundling Hospital sent out what it called “baby” or “mercy” trains.[5]

Organizations and families generally used the terms “family placement” or “out-placement” (“out” to distinguish it from the placement of children “in” orphanages or asylums) to refer to orphan train passengers.[5]

Widespread use of the term “orphan train” may date to 1978, when CBS aired a fictional miniseries entitled The Orphan Trains. One reason the term was not used by placement agencies was that less than half of the children who rode the trains were in fact orphans, and as many as 25 percent had two living parents. Children with both parents living ended up on the trains — or in orphanages — because their families did not have the money or desire to raise them or because they had been abused or abandoned or had run away. And many teenage boys and girls went to orphan train sponsoring organizations simply in search of work or a free ticket out of the city.[5]

The term “orphan trains” is also misleading because a substantial number of the placed-out children didn’t take the railroad to their new homes and some didn’t even travel very far. The state that received the greatest number of children (nearly one-third of the total) was New York. Connecticut, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania also received substantial numbers of children. For most of the orphan train era, the Children’s Aid Society bureaucracy made no distinction between local placements and even its most distant ones. They were all written up in the same record books and, on the whole, managed by the same people. Also, the same child might be placed one time in the West and the next time — if the first home did not work out — in New York City. The decision about where to place a child was made almost entirely on the basis of which alternative was most readily available at the moment the child needed help.[5]

The first Orphan Train

The first group of 45 children arrived in Dowagiac, Michigan, on October 1, 1854.[5] The children had traveled for days in uncomfortable conditions. They were accompanied by E. P. Smith of the Children’s Aid Society.[5] Smith himself had let two different passengers on the riverboat from Manhattan adopt boys without checking their references.[9] Smith added a boy he met in the Albany railroad yard — a boy whose claim to orphanhood Smith never bothered to verify.[5] At a meeting in Dowagiac, Smith played on his audience’s sympathy while pointing out that the boys were handy and the girls could be used for all types of housework.[5]

In an account of the trip published by the Children’s Aid Society, Smith said that in order to get a child, applicants had to have recommendations from their pastor and a justice of the peace, but it is unlikely that this requirement was strictly enforced.[5] By the end of that first day, fifteen boys and girls had been placed with local families. Five days later, twenty-two more children had been adopted. Smith and the remaining eight children traveled to Chicago where Smith put them on a train to Iowa City by themselves where a Reverend C. C. Townsend, who ran a local orphanage, took them in and attempted to find them foster families.[5] This first expedition was considered such a success that in January 1855 the society sent out two more parties of homeless children to Pennsylvania.[5]

Logistics of Orphan Trains

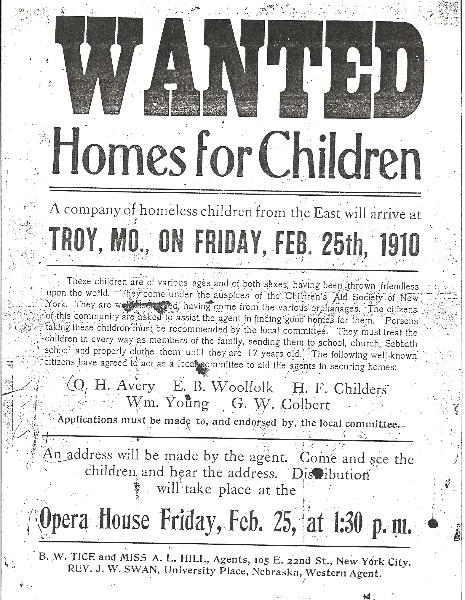

Committees of prominent local citizens were organized in the towns where orphan trains stopped. These committees were responsible for arranging a site for the adoptions, publicizing the event, and arranging lodging for the orphan train group. These committees were also required to consult with the Children’s Aid Society on the suitability of local families interested in adopting children.[9]

Brace’s system put its faith in the kindness of strangers.[10] Orphan train children were placed in homes for free and were expected to serve as an extra pair of hands to help with chores around the farm.[6] Families expected to raise them as they would their natural-born children, providing them with decent food and clothing, a “common” education, and $100 when they turned twenty-one.[5] Older children placed by The Children’s Aid Society were supposed to be paid for their labors.[6] Legal adoption was not required.[10]

According to the Children’s Aid Society’s “Terms on Which Boys are Placed in Homes,” boys under twelve were to be “treated by the applicants as one of their own children in matters of schooling, clothing, and training,” and boys twelve to fifteen were to be “sent to a school a part of each year.”[11] Representatives from the society were supposed to visit each family once a year to check conditions, and children were expected to write letters back to the society twice a year.[11] There were only a handful of agents to monitor thousands of placements.[10]

Before they boarded the train, children were dressed in new clothing, given a Bible, and placed in the care of Children’s Aid Society agents who accompanied them west.[1] Few children understood what was happening. Once they did, their reactions ranged from delight at finding a new family to anger and resentment at being ” placed out” when they had relatives ”back home.”[1]

Most children on the trains were white. An attempt was made to place non-English speakers with people who spoke their language.[1] German-speaking Bill Landkamer rode an orphan train several times as a preschooler in the 1920s before being accepted by a German family in Nebraska.[1]

Babies were easiest to place, but finding homes for children older than 14 was always difficult because of concern that they were too set in their ways or might have bad habits.[1] Children who were physically or mentally disabled or sickly were difficult to find homes for.[1] Although many siblings were sent out together on orphan trains, prospective parents could choose to take a single child, separating siblings.[12]

Many orphan train children went to live with families that placed orders specifying age, gender, and hair and eye color.[13] Others were paraded from the depot into a local playhouse, where they were put up on stage, thus the origin of the term “up for adoption.”[11] According to an exhibit panel from the National Orphan Train Complex, the children “took turns giving their names, singing a little ditty, or ‘saying a piece.”[11] According to Sara Jane Richter, professor of history at Oklahoma Panhandle State University, the children often had unpleasant experiences. “People came along and prodded them, and looked, and felt, and saw how many teeth they had.”[11]

Press accounts convey the spectacle, and sometimes auction-like atmosphere, attending the arrival of a new group of children. ”Some ordered boys, others girls, some preferred light babies, others dark, and the orders were filled out properly and every new parent was delighted,” reported The Daily Independent of Grand Island, NE in May 1912. ”They were very healthy tots and as pretty as anyone ever laid eyes on.”[1]

Brace raised money for the program through his writings and speeches. Wealthy people occasionally sponsored trainloads of children.[1] Charlotte Augusta Gibbs, wife of John Jacob Astor III, had sent 1,113 children west on the trains by 1884.[8] Railroads gave discount fares to the children and the agents who cared for them.[1]

Scope of the Orphan Train movement

The Children’s Aid Society’s sent an average of 3,000 children via train each year from 1855 to 1875.[1] Orphan trains were sent to 45 states, as well as Canada and Mexico. During the early years, Indiana received the largest number of children.[6] At the beginning of the Children’s Aid Society orphan train program, children were not sent to the southern states, as Brace was an ardent abolitionist.[12]

By the 1870s, the New York Foundling Hospital and the New England Home for Little Wanderers in Boston all had orphan train programs of their own.[9]

New York Foundling Hospital “Mercy Trains”

Main article: New York Foundling

The New York Foundling Hospital was established in 1869 by Sister Mary Irene Fitzgibbon of the Sisters of Charity of New York as a shelter for abandoned infants. The Sisters worked in conjunction with Priests throughout the Midwest and South in an effort to place these children in Catholic families. The Foundling Hospital sent infants and toddlers to prearranged Roman Catholic homes from 1875 to 1914.[1] Parishioners in the destination regions were asked to accept children, and parish priests provided applications to approved families. This practice was first known as the “Baby Train,” then later the “Mercy Train.” By the 1910s, 1,000 children a year were placed with new families.[14]

Criticisms

Linda McCaffery, a professor at Barton County Community College, explained the range of Orphan Train experiences: “Many were used as strictly slave farm labor, but there are stories, wonderful stories of children ending up in fine families that loved them, cherished them, [and] educated them.”[11]

Orphan train children faced obstacles ranging from the prejudice of classmates because they were ”train children” to feeling like outsiders in their families all their lives.[1] Many rural people viewed the orphan train children with suspicion, as incorrigible offspring of drunkards and prostitutes.[10]

Criticisms of the orphan train movement focused on concerns that initial placements were made hastily, without proper investigation, and that there was an insufficient follow-up on placements. (the more things change…these sick fuckers are too much).

Charities were also criticized (as they should be) for not keeping track of children placed while under their care.[8] In 1883, Brace consented to an independent investigation. It found the local committees were ineffective at screening foster parents. The supervision was lax. Many older boys had run away. But its overall conclusion was positive. The majority of children under fourteen were leading satisfactory lives.[10]

Applicants for children were supposed to be screened by committees of local businessmen, ministers, or physicians, but the screening was rarely very thorough.[5] Small-town ministers, judges, and other local leaders were often reluctant to reject a potential foster parent as unfit if he were also a friend or customer.[7]

Many children lost their identity through forced name changes and repeated moves.[15] In 1996, Alice Ayler said, “I was one of the luckier ones because I know my heritage. They took away the identity of the younger riders by not allowing contact with the past.”[16]

Many children placed out west had survived on the streets of New York, Boston or other large Eastern cities and generally they were not the obedient children many families expected.[8] In 1880, a Mr. Coffin of Indiana editorialized, “Children so thrown out from the cities are a source of much corruption in the country places where they are thrown… Very few such children are useful.”[17]

Some placement locations charged that orphan trains were dumping undesirable children from the East on Western communities.[8] In 1874, the National Prison Reform Congress charged that these practices resulted in increased correctional expenses in the West.[8]

Older boys wanted to be paid for their labor, sometimes asking for additional pay or leaving a placement to find a higher paying placement. It is estimated that young men initiated 80% of the placement changes.[8]

One of the many children who rode the train was Lee Nailing. Lee’s mother died of sickness; after her death, Lee’s father could not afford to keep his children.[citation needed] Another orphan train child was named Alice Ayler. Alice rode the train because her single mother could not provide for her children; before the journey, they lived off of “berries” and “green water.”[citation needed]

Catholic clergy maintained that some charities were deliberately placing Catholic children in Protestant homes to change their religious practices.[8] The Society for the Protection of Destitute Roman Catholic Children in the City of New York (known as the Protectory) was founded in 1863. The Protectory ran orphanages and place out programs for Catholic youth in response to Brace’s Protestant-centered program.[17] Similar charges of conversion via adoption were made concerning the placement of Jewish children.[8]

Not all orphan train children were true orphans, but were made into orphans by forced removal from their biological families to be placed out in other states.[8] Some claimed this was a deliberate pattern intended to break up immigrant Catholic families.[8] Some abolitionists opposed placements of children with Western families, viewing indentureship as a form of slavery.[8]

Orphan trains were the target of lawsuits, generally filed by parents seeking to reclaim their children.[8] Suits were occasionally filed by a receiving parent or family member claiming to have lost money or been harmed as the result of the placement.[8]

The Minnesota State Board of Corrections and Charities reviewed Minnesota orphan train placements between 1880 and 1883. The Board found that while children were placed hastily and without proper investigation into their placements, only a few children were “depraved” or abused. The review criticized local committee members who were swayed by pressure from wealthy and important individuals in their community. The Board also pointed out that older children were frequently placed with farmers who expected to profit from their labor. The Board recommended that paid agents replace or supplement local committees in investigating and reviewing all applications and placements.[8]

A complicated lawsuit arose from a 1904 Arizona Territory orphan train placement in which the New York Foundling Hospital sent 40 white children between the ages of 18 months and 5 years to be indentured to Catholic families in an Arizona Territory parish. The families approved by the local priest for placement were identified in the subsequent litigation as “Mexican Indian.” Nuns escorting these children were unaware of the racial tension between local Anglo and Mexican groups and placed white children with Mexican Indian families. A group of white men, described as “just short of a lynch mob,” forcibly took the children from the Mexican Indian homes and placed most of them with Anglo families. Some of the children were returned to the Foundling Hospital, but 19 remained with the Anglo Arizona Territory families. The Foundling Hospital filed a writ of habeas corpus seeking the return of these children. The Arizona Supreme Court held that the best interests of the children required that they remain in their new Arizona homes. On appeal, the U.S. Supreme Court found that a writ of habeas corpus seeking the return of a child constituted an improper use of the writ. Habeas corpus writs should be used “solely in cases of arrest and forcible imprisonment under color or claim of warrant of law,” and should not be used to obtain or transfer custody of children. These events were well-publicized at the time with newspaper stories titled “Babies Sold Like Sheep,” telling readers that the New York Foundling Hospital “has for years been shipping children in car-loads all over the country, and they are given away and sold like cattle.”[8]

End of the Orphan Train movement

As the West was settled, the demand for adoptable children declined.[8] Additionally, Midwestern cities such as Chicago, Cleveland, and St. Louis began to experience the neglected children problems that New York, Boston, and Philadelphia had experienced in the mid-1800s. These cities began to seek ways to care for their own orphan populations.[8]

In 1895, Michigan passed a statute prohibiting out-of-state children from local placement without payment of a bond guaranteeing that children placed in Michigan would not become a public charge in the State.[8] Similar laws were passed by Indiana, Illinois, Kansas, Minnesota, Missouri, and Nebraska.[8] Negotiated agreements between one or more New York charities and several western states allowed the continued placement of children in these states. Such agreements included large bonds as a security for placed children. In 1929, however, these agreements expired and were not renewed as charities changed their child care support strategies.[8]

Lastly, the need for the orphan train movement decreased as legislation was passed providing in-home family support. Charities began developing programs to support destitute and needy families limiting the need for intervention to place out children.[8]

Legacy of the program

Between 1854 and 1929, an estimated 200,000 American children traveled west by rail in search of new homes.[1]

The Children’s Aid Society rated its transplanted wards successful if they grew into “creditable members of society,” and frequent reports documented the success stories. A 1910 survey concluded that 87 percent of the children sent to country homes had “done well,” while 8 percent had returned to New York and the other 5 percent had either died, disappeared, or gotten arrested.[7]

Brace’s notion that children are better cared for by families than in institutions is the most basic tenet of present-day foster care.[5]

Organizations

The Orphan Train Heritage Society of America, Inc. founded in 1986 in Springdale, AR preserves the history of the orphan train era.[18] The National Orphan Train Complex in Concordia, KS is a museum and research center dedicated to the Orphan Train Movement, the various institutions that participated, and the children and agents who rode the trains.[19] The museum is located at the restored Union Pacific Railroad Depot in Concordia which is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The Complex maintains an archive of riders’ stories and houses a research facility. Services offered by the museum include rider research, educational material, and a collection of photos and other memorabilia.

The Louisiana Orphan Train Museum was founded in 2009[20] in a restored Union Pacific freight depot housed within Le Vieux Village Heritage Park in Opelousas, Louisiana.[21] The museum has a collection of original documents, clothing, and photographs of orphan train riders as both children and adults.[22] It focuses particularly on how the riders assimilated into the South Louisiana community, as the majority were legally adopted into their foster families.[23] The museum is also the seat for the Louisiana Orphan Train Society. Founded in 1990[20] and chartered in 2003, this society staffs the volunteer-run museum, conducts historical outreach, researches the stories of riders, and hosts a large annual event akin to a family reunion.[23]

Forwarding institutions

Some of the children who took the trains came from the following institutions: (partial list)[24]

- Angel Guardian Home

- Association for Befriending Children & Young Girls

- Association for Benefit of Colored Orphans

- Baby Fold

- Baptist Children’s Home of Long Island

- Bedford Maternity, Inc.

- Bellevue Hospital

- Bensonhurst Maternity

- Berachah Orphanage

- Berkshire Farm for boys

- Berwind Maternity Clinic

- Beth Israel Hospital

- Bethany Samaritan Society

- Bethlehem Lutheran Children’s Home

- Booth Memorial Hospital

- Borough Park Maternity Hospital

- Brace Memorial Newsboys House

- Bronx Maternity Hospital

- Brooklyn Benevolent Society

- Brooklyn Hebrew Orphan Asylum

- Brooklyn Home for Children

- Brooklyn Hospital

- Brooklyn Industrial school

- Brooklyn Maternity Hospital

- Brooklyn Nursery & Infants Hospital

- Brookwood Child Care

- Catholic Child Care Society

- Catholic Committee for Refugees

- Catholic Guardian Society

- Catholic Home Bureau

- Child Welfare League of America

- Children’s Aid Society

- Children’s Haven

- Children’s Village, Inc.

- Church Mission of Help

- Colored Orphan Asylum

- Convent of Mercy

- Dana House

- Door of Hope

- Duval College for Infant Children

- Edenwald School for Boys

- Erlanger Home

- Euphrasian Residence

- Family Reception Center

- Fellowship House for boys

- Ferguson House

- Five Points House of Industry

- Florence Crittendon League

- Goodhue Home

- Grace Hospital

- Graham Windham Services

- Greer-Woodycrest Children’s Services

- Guardian Angel Home

- Guild of the Infant Savior

- Hale House for Infants, Inc.

- Half-Orphan Asylum

- Harman Home for Children

- Heartsease Home

- Hebrew Orphan Asylum

- Hebrew Sheltering Guardian Society

- Holy Angels’ School

- Home for Destitute Children

- Home for Destitute Children of Seamen

- Home for Friendless Women and Children

- Hopewell Society of Brooklyn

- House of the Good Shepherd

- House of Mercy

- House of Refuge

- Howard Mission & Home for Little Wanderers

- Infant Asylum

- Infants’ Home of Brooklyn

- Institution of Mercy

- Jewish Board of Guardians

- Jewish Protector & Aid Society

- Kallman Home for Children

- Little Flower Children’s Services

- Maternity Center Association

- McCloskey School & Home

- McMahon Memorial Shelter

- Mercy Orphanage

- Messiah Home for Children

- Methodist Child Welfare Society

- Misericordia Hospital

- Mission of the Immaculate Virgin

- Morrisania City Hospital

- Mother Theodore’s Memorial Girls’ Home

- Mothers & Babies Hospital

- Mount Siani Hospital

- New York Foundling Hospital

- New York Home for Friendless Boys

- New York House of Refuge

- New York Juvenile Asylum (Children’s Village)[2]

- New York Society for Prevention of Cruelty to Children

- Ninth St. Day Nursery & Orphans’ Home

- Orphan Asylum Society of the City of Brooklyn

- Orphan House

- Ottilie Home for Children

In popular media

- Big Brother by Annie Fellow-Johnson, an 1893 children’s fiction book.

- Extra! Extra! The Orphan Trains and Newsboys of New York by Renée Wendinger, an unabridged nonfiction resource book and pictorial history about the orphan trains. ISBN 978-0-615-29755-2

- Good Boy (Little Orphan at the Train), a Norman Rockwell painting

- “Eddie Rode The Orphan Train”, a song by Jim Roll and covered by Jason Ringenberg

- Last Train Home: An Orphan Train Story, a 2014 historical novella by Renée Wendinger ISBN 978-0-9913603-1-4

- Orphan Train, a 1979 television film directed by William A. Graham.

- “Rider on an Orphan Train”, a song by David Massengill from his 1995 album The Return

- Orphan Train, a 2013 novel by Christina Baker Kline

- Placing Out, a 2007 documentary sponsored by the Kansas Humanities Council

- Toy Story 3, a 2010 Pixar animated film in which “Orphan Train” is referenced briefly at 00:02:04 – 00:02:07. Foster relationships are a reoccurring theme throughout the series.

- “Orphan Train”, a song by U. Utah Phillips[25][circular reference] released on disc 3 of the 4-CD compilation Starlight on the Rails: A Songbook in 2005

- Swamplandia!, a novel by Karen Russell, in which a character, Louis Thanksgiving, had been taken from New York to the MidWest on an Orphan Train by The New York Foundling Society after his unwed immigrant mother died in childbirth.

- Lost Children Archive, a novel by Valeria Luiselli, where the main character researches the forced movement of several demographics throughout the Americas’ history, including the Orphan Trains.

- The Copper Children, a play by Karen Zacarías premiered in 2020 at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival.[26]

- My Heart Remembers, a 2008 novel by Kim Vogel Sawyer, where the main character and her siblings were separated at a young age as orphans on the orphan train.

- “Orphan Train Series” by Jody Hedlund, a series about three orphaned sisters in the 1850s, the New York Children’s Aid Society, and the resettling of orphans from New York to the Midwest[27]

- 0.5 An Awakened Heart (2017)

- 1. With You Always (2017)

- 2. Together Forever (2018)

- 3. Searching for You (2018)

- ’’ Orphan Train, episode 16, season 2 of Dr. Quinn, Medicine Woman

Orphan Train children

- Eden Ahbez songwriter Nature Boy[28]

- Joe Aillet[29]

- John Green Brady[4]

- Andrew H. Burke[4]

- Henry L. Jost[30]

- Marion Parnell Costello Perry

- Frank Raymond Elliott

See also

- Home Children – similar program in the UK

Notes

- Warren, Andrea. “The Orphan Train”, The Washington Post, 1998

- “OUR CITY CHARITIES–NO. II.; The New-York Juvenile Asylum”. New York Times. January 31, 1860. Retrieved November 21, 2015.

- a “…from the most careful inquiry, they regard suited to have the charge of such children. Six years of experience have increased their caution and watchfulness in this matter, and they now require such guarantees on the part of the masters as will, in their judgment, most conduce to the good of their wards. Regular reports are required both from the children and their masters, and the agent of the asylum visits the greater part of the children when making his trips to locate new companies. In this way, very few are lost sight of, and the results thus far, in the case of those indentured within two years past, are very gratifying.” — ¶ 13

- b “On the 30th of June, 1851, the act of incorporation was passed. The corporators named in the act were Robert B. Minturn, Myndert Van Schaick, Robert M. Stratton, Solomon Jenner, Albert Gilbert, Stewart Brown, Francis R. Tillou, David S. Kennedy, Joseph B. Collins, Benjamin F. Butler, Isaac T. Hopper, Charles Partridge, Luther Bradish, Christopher Y. Wemple, Charles O’Conor, John D. Russ, John Duer, Peter Cooper, Apollos R. Wetmore, Frederick S. Winston, James Kelly, Silas C. Herring, Rensselaer N. Havens, and John W. Edmonds” — ¶ 7

- “Do Orphanages Still Exist in America? The Truth About “Adopting an Orphan””. American Adoptions. Retrieved 18 June 2022.

- “American Experience . The Orphan Trains | PBS”. www.pbs.org. Retrieved 2016-11-28.

- “Orphan Trains”. www.nytimes.com. Retrieved 2016-11-28.

- “History”, Children’s Aid Society

- “Trains Ferried Waifs To New Lives On The Prairie”. tribunedigital-sunsentinel. Retrieved 2016-11-28.

- S., Trammell, Rebecca (2009-01-01). “Orphan Train Myths and Legal Reality”. The Modern American. 5 (2).

- O’Connor, Stephen (2004-03-01). Orphan Trains: The Story of Charles Loring Brace and the Children He Saved and Failed. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226616674.

- “American Experience. The Orphan Trains | PBS”. www.pbs.org. Retrieved 2016-11-28.

- Scheuerman, Dan. “Lost Children: Riders on the Orphan Train”, Humanities, November/December 2007 | Volume 28, Number 6

- Writer, Patricia Middleton Staff. “Orphan trains focus of upcoming program”. McPhersonSentinel. Retrieved 2016-11-28.

- “They survived Minnesota’s orphan trains to celebrate life – Twin Cities”. 30 September 2015. Retrieved 2016-11-28.

- Dianne Creagh, “The Baby Trains: Catholic Foster Care and Western Migration, 1873–1929,” Journal of Social History (2012) 46#1 pp 197–218 online

- “Orphan Train”. www.americanbar.org. Retrieved 2016-11-28.

- “Students Learn About Orphan Train”. NewsOK.com. 1996-06-12. Retrieved 2016-11-28.

- Nelson, Claudia (2003-05-13). Little Strangers: Portrayals of Adoption and Foster Care in America, 1850-1929. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0253109809.

- “Orphan Train Heritage Society of America, Inc. (OTHSA) – Encyclopedia of Arkansas”. www.encyclopediaofarkansas.net. Retrieved 2016-11-28.

- inc., designed by: logicmaze. “The 8 Wonders of Kansas History – A Kansas Sampler Foundation Project”. www.kansassampler.org. Retrieved 2016-11-28.

- Raghavan, Nalini (2013-07-02). “The Louisiana Orphan Train Museum”. Country Roads Magazine. Retrieved 2021-05-15.

- “Louisiana Orphan Train Museum”. St. Landry Parish Tourist Commission. Retrieved 2021-05-15.

- “Louisiana Orphan Train Museum – City of Opelousas”. Retrieved 2021-05-15.

- Johnson, William. “Louisiana loses last Orphan Train rider”. The Daily Advertiser. Retrieved 2021-05-15.

- DiPasquale, Connie. “Orphans Trains of Kansas”, The Kansas Collection

- “Utah Phillips”. Wikipedia.

- “O!”.

- Orphan Train Series

- “Rewriting Love Underneath the Hollywood Sign”. Vogue. 2016-02-08. Retrieved 2021-09-19.

- “Home”.

- Johnson, Kristin F. (2011-01-01). The Orphan Trains. ABDO. ISBN 978-1-61478-449-4.

Further reading

- Clarke, Herman D. (2007). Kidder, Clark (ed.). Orphan Trains and Their Precious Cargo: The Life’s Work of Rev. H. D. Clarke. Westminster, Md.: Heritage Books. ISBN 978-0788417559.

- Creagh, Dianne. “The Baby Trains: Catholic Foster Care and Western Migration, 1873–1929”, Journal of Social History (2012) 46(1): 197–218.

- Holt, Marilyn Irvin. The Orphan Trains: Placing Out in America. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1992. ISBN 0-8032-7265-0

- Johnson, Mary Ellen, ed. Orphan Train Riders: Their Own Stories. (2 vol. 1992),[ISBN missing]

- Magnuson, James and Dorothea G. Petrie. Orphan Train. New York: Dial Press, 1978. ISBN 0-8037-7375-7

- O’Connor, Stephen. Orphan Trains: The Story of Charles Loring Brace and the Children He Saved and Failed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2001. ISBN 0-3958-4173-9

- Patrick, Michael, and Evelyn Trickel. Orphan Trains to Missouri. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1997.[ISBN missing]

- Patrick, Michael, Evelyn Sheets, and Evelyn Trickel. We Are Part of History: The Story of the Orphan Trains. Santa Fe, NM: The Lightning Tree, 1990.[ISBN missing]

- Riley, Tom. The Orphan Trains. New York: LGT Press, 2004. ISBN 0-7884-3169-2

- Donna Nordmark Aviles. “Orphan Train To Kansas – A True Story”. Wasteland Press 2018. ISBN 978-1-68111-219-0

- Renee Wendinger. “Extra! Extra! The Orphan Trains and Newsboys of New York”. Legendary Publications 2009. ISBN 978-0-615-29755-2

- Clark Kidder. “Emily’s Story – The Brave Journey of an Orphan Train Rider”. 2007. ISBN 978-0-615-15313-1

External links

- West by Orphan Train – A documentary film by Colleen Bradford Krantz and Clark Kidder, 2014

- DiPasquale, Connie. “Orphan Trains of Kansas”

- “He rode the ‘Orphan Train’ across the country” – CNN

- “Orphan train riders, offspring seek answers about heritage” – USA Today

- “The Orphan Train”– CBS

- “98-Year-Old Woman Recounts Experience As ‘Orphan Train’ Rider”– CBS

- The Cawker City Public Record, 8 April 1886

- “Placing Out” Department form

- “The Orphan Trains”, American Experience, PBS

- National Orphan Train Complex

Leave a Reply