USS Nepenthe (SP-112), a luxury yacht belonging to James Deering

Nepenthe was built as a civilian yacht, of a type designated “houseboat” at the time to describe the relative focus on livability in comparison with the usual powerboats, in 1917 by the Mathis Yacht Building Company at Camden, New Jersey with completion in December 1916. The yacht was built for industrialist James Deering of Chicago, New York and Miami, Florida and was docked adjacent to his Miami estate Vizcaya.

The U.S. Navy acquired Nepenthe from her owner on 7 June 1917 for use during World War I. She was commissioned as USS Nepenthe (SP-112). Assigned to the 7th Naval District, Nepenthe served in Florida waters. However, she proved unsuitable for Navy service, and was returned to her owner on 5 October 1917.

James Deering was an American executive in the management of his family’s Deering Harvester Company and later International Harvester, as well as a socialite and an antiquities collector. His older half-brother was the arts patron Charles Deering. He built his landmark Vizcaya estate, where he was an early 20th-century resident on Biscayne Bay in the present day Coconut Grove district of Miami, Florida. Begun in 1910, with architecture and gardens in a Mediterranean Revival style, Vizcaya was his passionate endeavor with artist Paul Chalfin, and his winter home from 1916 to his death in 1925.

His father, who had inherited the family woolen mill and owned large tracts of land in the Northeast, invested in a farm-equipment manufacturing company that he renamed the Deering Harvester Company. In 1873, he moved the family to Chicago, Illinois. The Deering Harvester Company’s reaper machinery enabled farmers in the US Midwest to harvest an acre of grain per hour, an increase in productivity sufficient to enhance the profitability of Midwest agriculture significantly. The Deering Harvester Company grew in value, so that by the end of the 19th century the Deerings had become one of America’s wealthiest families.

In 1902, J.P. Morgan and Company purchased Deering Harvester and McCormick Reaper Company and merged them to form the International Harvester Corporation, the largest producer of agricultural machinery in the U.S. James Deering became vice-president of the new corporation, responsible for the three Illinois manufacturing plants. In 1909, he was phased out of daily company affairs by J.P. Morgan interests.

By the turn of the century, Deering owned homes on Lake Shore Drive in Chicago, in the countryside near Evanston, Illinois, in New York City, and in Paris. His name appeared in social columns as an arts connoisseur, socialite, international traveler, and cultural ambassador. He hosted events for French dignitaries at his New York and Chicago residences. In 1906, for Deering’s work in promoting agricultural technology development in France, he was awarded the Légion d’honneur (“National Order of the Legion of Honour”).

Construction of Vizcaya began in 1912, and Deering officially began his occupancy on Christmas Day 1916, when he arrived aboard Nepenthe. The yacht was kept constantly ready for use and equipped with the same china, monogrammed French linens, and fine accessories as the mansion. From Christmas 1916 until his death in 1925 Deering typically resided at Vizcaya from the end of November to the middle of April entertaining guest that included Lillian Gish, President Warren Harding, Marion Davies, William Jennings Bryan, Thomas Edison and John Singer Sargent. In April 1917, Sargent was invited to cruise the Florida Keys aboard Nepenthe with James and Charles Deering. He joined the cruise “reluctantly”, doing some watercolor sketches (including Derelicts, 1917), as he wanted to stay at the mansion for its “mine of sketching.”

Deering was happiest aboard a boat, preferring seven- to ten-day cruises aboard Nepenthe. The yacht was sunk, a year after Deering’s death aboard the SS City of Paris (1920), in the 1926 Miami hurricane. Nepenthe was salvaged and sold.

- Colton, Tim (June 6, 2018). “Mathis Yacht Building, Camden and Gloucester City NJ”. ShipbuildingHistory. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- Construction & Repair Bureau (Navy) (November 1, 1918). Ships’ Data U.S. Naval Vessels. Washington D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 315. Retrieved 8 September 2018.

- “Born Again”. MotorBoating. August 1999. p. 90. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- 1918-1919 Philadelphia Year Book. Philadelphia, Pa.: Philadelphia Chamber of Commerce. 1919. p. A44. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- Lammers (Historian), Jonathan (July 20, 2010). “National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, Renown“ (PDF). p. Sec. 8, p. 2. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- “Lost Spaces and Stories of Vizcaya — Boating and Leisure (Boat Landing, Nepenthe Yacht and Psyche Cruiser, and Boat House)” (PDF). Vizcaya Museum & Gardens. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- “James Deering, the Patron”. Vizcaya Museum & Gardens. 2018. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- “Life at Vizcaya”. Vizcaya Museum & Gardens. 2018.

- Bartle, Annette (1989). “Vizcaya retains touch of the Renaissance”. Doylestown Intelligencer (April 02, 1989). Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- “Deering/McCormick: The Dynasties Second Merger”. Classic Chicago Magazine. March 19, 2017. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- Madsen, Annelise K.; Ormond, Richard; Broadway, Mary (2018). John Singer Sargent & Chicago’s Gilded Age. Chicago, Illinois: The Art Institute of Chicago. p. 112. ISBN 9780300232974. LCCN 2017056054. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- WPBT2 PBS (2009). “Life at Vizcaya”. Community Foundation of South Florida, Inc. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- Naval History And Heritage Command. “Nepenthe (S. P. 112)”. Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Naval History And Heritage Command. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- Sandler, Nathaniel; Wouters (Curator), Gina (2016). “Maritime Vizcaya – Boats and Boating Culture at the Estate (December 2016)”. Vizcaya Museum & Gardens. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- NavSource Online: Section Patrol Craft Photo Archive: Nepenthe (SP 112)

- Derelicts, John Singer Sargent, sketched while cruising aboard Nepenthe

- Griswold, Mac and Weller, Eleanor. “The Golden Age of American Gardens, proud owners-private estates 1890 – 1940”. Harry N. Abrams. N.Y. 1991. ISBN 0-8109-2737-3. pp. 174–76

- “James Deering”. Farmton Tree Farm. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- Griswold, Mac and Weller, Eleanor. “The Golden Age of American Gardens, proud owners-private estates 1890 – 1940”. Harry N. Abrams. N.Y. 1991. ISBN 0-8109-2737-3. p. 174

- “Untitled Document”. Archived from the original on 2010-04-12. Retrieved 2010-04-17. accessed 4/11/2010

- “Untitled Document”. Archived from the original on 2010-09-27. Retrieved 2010-04-17.

- “Life at Vizcaya”. Vizcaya Museum & Gardens. 2018. Archived from the original on 2019-08-12.

- Bartle, Annette (1989). “Vizcaya retains touch of the Renaissance”. Doylestown Intelligencer (April 02, 1989). Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- Wadman, Rex W. (January 1917). “Winter Racing in Florida — The Third Annual Regatta at Miami This Month Promises to Be the Most Pretentious Affair of the Kind Ever Held in This Country”. Motor Boating. Vol. 19, no. 1. pp. 11–12. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- Capó Jr., Julian (2017). Welcome to Fairyland: Queer Miami before 1940. University of North Carolina Press. p. 102. ISBN 9781469635217. Retrieved January 5, 2021.

- “Timeline”. vizcaya.org. Archived from the original on 2015-08-23. Retrieved 21 June 2021.

1908 James Deering retires from International Harvester.

- “James Deering, the Patron”. vizcaya.org. Archived from the original on 2015-08-22. Retrieved 21 June 2021.

James Deering James Deering James Deering (1859–1925) was a retired millionaire and a bachelor in his early fifties when he undertook the challenge to build an elaborate estate in South Florida. He was afflicted with pernicious anemia, a condition for which doctors recommended sunshine and a warm climate: Vizcaya became the place where he hoped to restore his health….Deering’s health began to fail even before Vizcaya was completed.

- Official Vizcaya Museum and Gardens website

- Architecture portal

- Witold Rybczynski and Laurie Olin, authors, Steven Brooke, photographer. Vizcaya: An American Villa and Its Makers (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006).

- Laurie Ossman (text) and Bill Sumner (photographs). Visions of Vizcaya (Miami: Vizcaya Museum and Gardens/Miami-Dade County, 2006).

- Kathryn C. Harwood. Lives of Vizcaya Miami: Banyan Books, 1985.

- Griswold, Mac and Weller, Eleanor. “The Golden Age of American Gardens, proud owners-private estates 1890 – 1940”. Harry N. Abrams. N.Y. 1991. ISBN 0-8109-2737-3.

Nepenthe Productions, the production company of Martin Rosen

Martin Gerald Rosen is an American filmmaker and theater producer. He directed the animated film adaptations of Watership Down (1978) and The Plague Dogs (1982), both from the Richard Adams novels. Rosen was originally the producer of Watership Down but took over as director after John Hubley, the original director, left after disagreements with Rosen. He also wrote the screenplay for it. This was the first of two novels by Richard Adams he adapted.

Watership Down has developed a reputation as a distressing children’s text, with Ed Power of The Independent describing the film in a 40th anniversary retrospective as a “classic” but which “arguably traumatised an entire generation”. More recently, film critics and scholars have defended Watership Down‘s potential value for child audiences. Children’s media scholar Catherine Lester argues that the violence is “never without a specific narrative or moral purpose” and that discussions of the film’s effect upon children require “greater nuance” that acknowledges the complexity and variety of children as viewers and how they respond to films.

In 1982 he also produced, directed and wrote the screenplay for another animated feature based on an Adams novel, The Plague Dogs (1982). The Plague Dogs is the first non-family-oriented MGM animated film, and marks their first adult animated feature by the studio. The film’s story is centered on two dogs named Rowf and Snitter, who escape from a research laboratory in Great Britain. In the process of telling the story, the film highlights the cruelty of performing vivisection and animal research for its own sake (though Rosen said that this was not an anti-vivisection film, but an adventure), an idea that had only recently come to public attention during the 1960s–70s.

Rosen produced Smooth Talk (1986), which won the Sundance Grand Prize. His last film as director was Stacking (1987). His last project as producer was the animated Watership Down TV series in 1999.

- Lui, John (October 14, 2015). “Straitstimes.com”. The Straits Times. Retrieved March 18, 2016.

- “Richard Adams’ Estate Wins Back Rights to ‘Watership Down’ in English High Court Case”, by Andreas Wiseman, Deadline.com

- Case Detail – WATERSHIP DOWN ENTERPRISES, LLC v. SIROCCO PRODUCTIONS, INC Et Al

- “Martin Rosen – Rotten Tomatoes”. Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved March 11, 2016.

- “Martin Rosen – IMDb”. IMDb. Retrieved March 11, 2016.

- Nepenthe Productions

- Power, Ed (20 October 2018). “How Watership Down terrified an entire generation”. The Independent. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- Denham, Jess (30 March 2016). “Channel 5 criticised for airing ‘traumatic’ Watership Down at Easter”. The Independent. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- “Bunny bloodbath on Easter Sunday sparks outrage as Channel 5 air Watership Down”. Daily Record. 16 April 2017. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- BBFC Examiner’s Report, 15 February 1978

- “From the Archive.. viewing a ‘repressive rabbit regime'”. British Board of Film Classification. Archived from the original on 9 April 2012. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- “Watership Down”. British Board of Film Classification. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

- Whitehead, Ted (21 October 1978). “Sententious”. The Spectator. p. 30.

- Lester, Catherine (13 December 2018). “Watership Down: family-friendly BBC version risks losing the power of epic original”. The Conversation. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

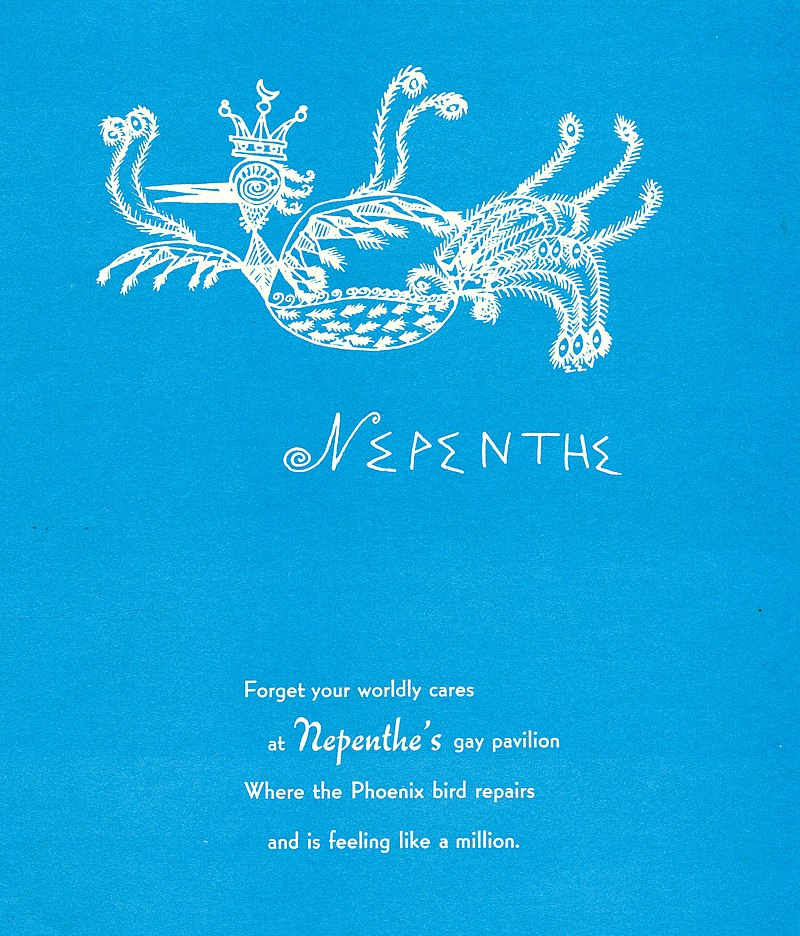

Nepenthe (restaurant), a restaurant in Big Sur, California

Nepenthe is a restaurant in Big Sur, California, built by Bill and Madelaine “Lolly” Fassett and first opened in 1949. It was built around a cabin first constructed in 1925. It is known for the miles-long panoramic view of the south coast of Big Sur from the outdoor terrace and its California/Greek Mediterranean menu featuring locally and California-grown food.

Orson Welles and his wife Rita Hayworth bought the cabin around which the restaurant is built from the Trail Club of Jolon on a whim as a romantic getaway. The couple measured the windows for curtains, but never returned. The Fassetts bought the cabin and surrounding land from Welles and Hayworth in 1947 for $22,000. They named the restaurant after a potion used by the ancient gods to induce forgetfulness from pain or sorrow.

The restaurant is located 29 miles (47 km) south of Carmel, California and about 800 feet (240 m) above the coast. The business has had to endure multiple closures of Highway 1 since its founding due to fire, floods, and mudslides. The restaurant became a favorite of Henry Miller. He later lived on Partington Ridge but returned often to the restaurant and became close friends with owner Bill Fassett. The restaurant became a social hub for artists, poets, actors and other creative individuals on the coast, attracting people like artists Man Ray, Harry Dick Ross, and Janko Varda; author Anais Nin; writer Ernest Hemingway and Hunter S. Thompson; poet Eric Barker; actor Clint Eastwood; and scientist Giles Healey.

In 1964, Lolly Fassett added the Phoenix Shop featuring gifts and local artist’s wares, and in 1992, they opened the walk-up, casual Café Kevah. The owners donate 10 percent of the restaurant’s net profit to community activities and organizations, including the Big Sur Health Center and the Big Sur Volunteer Fire Brigade.

The terrace was formerly dominated by a large coastal live oak that died in the 1970s. After it died, sculptor Edmund Kara resurrected the trunk of the tree with a sculpture of the rising Phoenix, a standard symbol for Nepenthe. The bird is one piece with legs made of bronze.

A dance scene from the 1965 film The Sandpiper starring Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton featured a set replicating the restaurant’s terrace. The nightclub scene from the 1997 thriller Kiss the Girls was filmed in the restaurant

- Big Sur: Exploring California’s Tourist Hot Spot Turned Ghost Town

- “Nepenthe Big Sur Stories and Folktales”. 2005-02-26. Archived from the original on February 26, 2005. Retrieved 2017-12-19.

- “California Bucket List”. Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Archived from the original on 2017-12-24. Retrieved 2017-12-24.

- Anderson, Mark C. “Nepenthe still swinging as it turns 60”. Monterey County Weekly. Retrieved 2017-12-19.

- “The Nepenthe cabin where it all began 60 years ago”. The Mercury News. 24 April 2009. Archived from the original on 22 December 2017. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- “Nepenthe Restaurant – Big Sur, California – Gil’s Thrilling (And Filling) Blog”. Gil’s Thrilling (And Filling) Blog. 2012-07-18. Archived from the original on 2017-12-22. Retrieved 2017-12-19.

- “Granddaughter writes history of Nepenthe”. San Francisco Chronicle. November 13, 2009. Archived from the original on 14 August 2016. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- “Rita and Orson”. Archived from the original on 2017-12-24. Retrieved 2017-12-19.

- Norman, Jeff (2004). Big Sur. Big Sur Historical Society. Charleston, S.C.: Arcadia Pub. ISBN 9780738529134. OCLC 58788953.

- Romney., Steele (2009). My Nepenthe: Bohemian Tales of Food, Family, and Big Sur. Kansas City, MO: Andrews McMeel Pub. p. 33. ISBN 9780740779145. OCLC 316831962. Archived from the original on 2018-01-08.

- Chambers, Andrea; Powell, Lee (November 13, 1989). “A Candid New Biography Tells of the Shocking Childhood That Destroyed Rita Hayworth”. PEOPLE.com. Archived from the original on April 20, 2017. Retrieved 2017-12-24.

- “Granddaughter writes history of Nepenthe”. SFGate. 2009-11-13. Archived from the original on 14 August 2016. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- “The Nepenthe cabin where it all began 60 years ago”. The Mercury News. 2009-04-24. Archived from the original on 2017-12-22. Retrieved 2017-12-19.

- “Tales from Nepenthe: Ping Pong with Henry Miller”. 2005-02-26. Archived from the original on February 26, 2005. Retrieved 2017-12-20.

- Thurman, Chuck. “Nepenthe celebrates its 50th anniversary as a cultural landmark”. Monterey County Weekly. Retrieved 2017-12-20.

- When The Going Gets Weird the twisted life and times of Hunter S. Thompson, Peter O. Whitmer, Hyperion, 1993

- “Nepenthe cares for the community”. 2013-07-27. Archived from the original on August 17, 2016. Retrieved 2017-12-20.

- “The Phoenix Bird”. Nepenthe. Archived from the original on 2017-12-24. Retrieved 2017-12-24.

- Wright, Tommy (February 22, 2017). “Highway 1: Pfeiffer Canyon Bridge condemned”. The Mercury News. Archived from the original on 26 February 2017. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- “Isolated Big Sur Businesses Stay Open with Helicopter Access and ‘Island’ Luaus”. Eater SF. Archived from the original on 2017-12-22. Retrieved 2017-12-20.

- “A Celebration of Elizabeth Taylor: Her Big Sur Film “The Sandpiper””. The Central Coast Traveler. 2012-03-24. Archived from the original on 2017-12-22. Retrieved 2017-12-20.

- “Kiss the Girls (1997) – IMDb”

Nepenthes (sculpture), a series of four sculptures by artist Dan Corson

Nepenthes is a series of four sculptures by artist Dan Corson, installed in 2013 along Northwest Davis Street in the Old Town Chinatown neighborhood of Portland, Oregon, in the United States. The work was inspired by the genus of carnivorous plants of the same name, known as tropical pitcher plants. The sculptures are 17 feet (5.2 m) tall and glow in the dark due to photovoltaics. According to Corson and the Regional Arts & Culture Council (RACC), which maintains the sculpture series, the work and genus are named after the “magical Greek potion that eliminates sorrow and suffering”. The agency said that Nepenthes “insert[s] a quirky expression of nature into an urban environment” and celebrates the “unique and diverse community” of Portland’s Old Town Chinatown neighborhood.

Nepenthes received a mixed reception. RACC has reportedly received mixed reviews from “folks who felt that [the sculptures] sort of appeared out of nowhere and were a little random in their placement.” One spokesperson for the agency said people directly involved with the project were happy with the final product. Willamette Week‘s Richard Spear called the work an “atrocity”, “garish and cheap-looking.” He wrote that the pieces were more appropriate for an outlet mall in Kissimmee, Florida, “come across as dumbed-down knockoffs of Chihuly glass”, and “could be used as props in a high-school staging of The Little Mermaid“. Following installation, the owner of a gallery located next to one of the sculptures compared them to lava lamps and expressed hope that they would be run over by a truck.

On the other hand, the American media company PSFK called the designs “startling”, noting that as street lamps, “they are far from your typical metal and light bulb structures.” John Metcalfe of CityLab writes, “Portland residents have had the unexpected pleasure of walking through an alien greenhouse of huge, bizarrely colored carnivorous plants.” Art and Architecture refers to them as “amazing structures”. The online trend community blog Trend Hunter calls the work “incredibly vibrant” and “visually striking”, and says it “gives ‘urban jungle’ a completely new meaning”. The architecture and design weblog Inhabitat calls them “beautiful, quirky and exotically colorful.”

The daily web magazine Designboom says of the statues, “each fiberglass sculpture glows from within at night creating an intriguing and dramatic street presence”, “curvaceous shadows animate the sidewalk on sunny days”, and the sculptures are “touchable: many people are drawn to the form or surfaces and feel compelled to stroke them as they walk by”. Kristi in Arts, a Portland public art blog, noting that, “The goal is for the sculptures to create an inviting pathway leading people from the Pearl District into Old Town” comments, “I wish they had installed about 10 more leading further into Northwest,” and then adds, “Not only do they look fantastic, but they are powered by solar and run LED lights. Nice work, Portland.”

- Speer, Richard (July 3, 2013). “Nepenthes and Inversion: +/–: New public art pieces inspire, infuriate”. Willamette Week. Portland, Oregon. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved October 13, 2013.

- “Installation of Dan Corson’s “Nepenthes” now underway”. Regional Arts & Culture Council. May 9, 2013. Archived from the original on October 17, 2013. Retrieved October 13, 2013.

- Hottman, Sara (May 22, 2013). “New sculptures on Northwest Davis Street part of revitalization project”. The Oregonian. Portland, Oregon. Archived from the original on October 17, 2013. Retrieved October 13, 2013.

- Paisley open for business Archived 2015-06-17 at the Wayback Machine Edmonton Sun, July 8, 2014

- Gonzalez, Lea (July 2, 2013). “Carnivorous Plant Solar Lamps Glow in City Streets”. PSFK. Archived from the original on February 23, 2022. Retrieved June 7, 2015.

- Metcalfe, John (July 5, 2013). “A Closer Look at Portland’s Giant, Carnivorous Street Lights”. CityLab. Archived from the original on June 8, 2015. Retrieved June 8, 2015.

- Art and Architecture: Nepenthes in Portland, Oregon, by Dan Corson Archived 2015-06-17 at the Wayback Machine Oct 20, 2014

- Nepenthes by Dan Corson Turns Portland into an Eco Jungle Archived 2022-02-23 at the Wayback Machine by Meghan Young, Trend Hunter, Jul 4, 2013

- “Dan Corson’s Solar-Powered Sculptures in Portland, Oregon are Inspired by Quirky Tropical Plants, by Lidija Grozdanic, 07/04/13”. Archived from the original on 2015-07-06. Retrieved 2015-06-15.

- energy-creating nephenthes plant sculptures by dan corson Archived 2016-02-24 at the Wayback Machine designboom, Jun 29, 2013

- Nepenthes: Solar-Powered Sculptures Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine Kristi in Arts, Public Art, June 18, 2013

- Official website

“Nepenthe” (Star Trek: Picard), an episode of Star Trek: Picard

The first season of the American television series Star Trek: Picard features the character Jean-Luc Picard after he retired from Starfleet following the destruction of the planet Romulus. Living on his family’s vineyard in 2399, Picard is drawn into a new adventure when he is visited by the daughter of android lieutenant commander Data. The season was produced by CBS Television Studios in association with Secret Hideout, Weed Road Pictures, Escapist Fare, and Roddenberry Entertainment, with Michael Chabon serving as showrunner.

Patrick Stewart stars as Picard, reprising his role from the series Star Trek: The Next Generation as well as other Star Trek media. Alison Pill, Isa Briones, Harry Treadaway, Michelle Hurd, Santiago Cabrera, and Evan Evagora also star. Stewart announced the series in August 2018, after being convinced to return to the role by creators Akiva Goldsman, Chabon, Kirsten Beyer, and Alex Kurtzman. Chabon was named sole showrunner ahead of filming, which took place from April to September 2019 in California. The producers focused on differentiating the season from previous franchise installments and rehabilitating the Romulan and Borg species. The story and setting take inspiration from the political landscape of Brexit and Donald Trump, as well as the Syrian refugee crisis. The season features special guest stars reprising their roles from The Next Generation and other Star Trek media.

The season premiered on the streaming service CBS All Access on January 23, 2020, and ran for 10 episodes through March 26. It was released to new viewership records for the service and generally positive reviews from critics who highlighted Stewart’s performance and the focus on character over action. However, they criticized the season’s slow pace and complex story, and its darker tone than previous Star Trek series was controversial with critics and franchise fans alike. The season won a Primetime Emmy Award for its Prosthetic Makeup, and received several other awards and nominations.

Episode 7, “Nepenthe” written by Doug Aarniokoski and directed by Samantha Humphrey and Michael Chabon aired March 5, 2020 is described below.

When Jurati was approached by Oh, the latter used a Vulcan mind meld to reveal the horrifying potential consequences of allowing synthetic life like Soji to exist. Jurati agreed to help destroy her, and ingested a tracking device. Narek now uses that to track La Sirena until a guilt-ridden Jurati takes an injection that places her in a coma and stops the tracking. Elnor’s attempts to protect Hugh on the Artifact are unsuccessful when Narissa fatally wounds Hugh. Before dying, Hugh gives Elnor a device to signal Seven of Nine’s vigilante group, the Fenris Rangers. On Nepenthe, Picard reunites with his old friends and colleagues William Riker and Deanna Troi, whose son Thad died after the medical procedure he required was banned as part of the synthetic ban. Riker, Troi, and their daughter Kestra give shelter to Picard and Soji until La Sirena arrives. Troi and Riker can see Soji’s pain following Narek’s betrayal, and help Picard begin to earn her trust. The family also try to help Soji come to terms with being an android, and are able to help identify the location from her dream.

Chabon saw the seventh episode as a pause or respite for the characters since all the seasons elements were well set by that point, and Picard had finally crossed paths with Soji. This led to the introduction of Riker and Troi, with their backstory tied into the idea that they brought their family to the planet for their son’s attempted recovery. The scenes at Riker and Troi’s cabin were filmed at the Universal backlot in a cabin first used by The Great Outdoors (1988). The seventh episode also includes Del Arco’s final scenes as Hugh in which he watches fellow former-Borg drones being executed before dying himself.

- Goldberg, Lesley (January 12, 2020). “‘Star Trek: Picard’ Renewed for Season 2 at CBS All Access”. The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on January 13, 2020. Retrieved January 20, 2020.

- Pirrello, Phil (March 6, 2020). “”It Was a Devastating Day:” How ‘Star Trek’ Actor Crafted Surprising Scene”. The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on March 8, 2020. Retrieved March 8, 2020.

- Patten, Dominic (March 5, 2020). Star Trek: Picard Podcast: Reunion With Riker & Building The Borg. Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved March 8, 2020.

- Patten, Dominic (March 12, 2020). Star Trek: Picard Podcast: Picking Up The ‘Broken Pieces’ & Shaking The Etch A Sketch. Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved March 26, 2020.

- TrekCore.com [@TrekCore] (March 5, 2020). “The Troi-Riker residence is a log cabin built on the Universal backlot, first used in the 1988 John Candy/Dan Ackroyd comedy “The Great Outdoors.”” (Tweet). Archived from the original on March 6, 2020. Retrieved March 8, 2020 – via Twitter.

- Pirrello, Phil (March 26, 2020). “Patrick Stewart Breaks Down ‘Star Trek: Picard’ Finale Shocker”. The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on March 26, 2020. Retrieved March 28, 2020.

Nepenthe, the setting of Norman Douglas’ 1917 novel South Wind

South Wind is a 1917 novel by British author Norman Douglas. It is Douglas’s most famous book and his only success as a novelist. It is set on an imaginary island called Nepenthe, located off the coast of Italy in the Tyrrhenian Sea, a thinly fictionalized description of Capri‘s residents and visitors. The narrative concerns twelve days during which Thomas Heard, a bishop returning to England from his diocese in Africa, yields his moral vigour to various influences. Philosophical hedonism pervades much of Douglas’s writing, and the novel’s discussion of moral and sexual issues caused considerable debate.

The South Wind of the title is the Sirocco, which wreaks havoc with the islanders’ sense of decency and morality. Much of the natural detail in the book is provided by Capri and other Mediterranean locations that Douglas knew well. The island’s name Nepenthe denotes a drug of Egyptian origin (mentioned in the Odyssey) which was capable of banishing grief or trouble from the mind. The novel was written in Capri and in London, and after its publication in June 1917 it went through seven editions rapidly, achieving startling large-scale success. Critics at the time complained about the lack of a well-constructed plot. The book was adapted for the stage in London in 1923 by Isabel C. Tippett, and Graham Greene considered the possibility of writing a film script based on it.

In Dorothy Sayers‘s 1926 detective novel Clouds of Witness, Lord Peter Wimsey goes through the possessions of a murdered man – a young British man living in Paris, whose morality had been put in question. Finding a copy of South Wind Wimsey remarks “Our young friend works out very true to type”. In Robert McAlmon‘s Being Geniuses Together, he mentions meeting Norman Douglas in Venice in 1924, by which time he says South Wind was a minor classic. Apparently when sales continued for years afterwards, Douglas, to whom only a small amount was paid to begin with, received no further payments.

- Ousby, Ian (1996). Cambridge Paperback Guide to Literature in English. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-43627-3.

- Stringer, Jenny (1996). The Oxford Companion to Twentieth-century Literature in English. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780192122711.

- Orel, Harold (1992). Popular Fiction in England, 1914-1918. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 9780813117898.

- Rennison, Nick (2009). London Blue Plaque Guide (4th ed.). The History Press. ISBN 9780752499963.

- South Wind at Project Gutenberg.

- South Wind, Literary Encyclopedia.

- Norman Douglas, Encyclopædia Britannica.

- McAlmon, Robert, Being Geniuses Together 1920-1930 (revised edition with additional chapters by Kay Boyle), North Point Press, San Francisco, 1984, p. 134

Nepenthe is a fictional medicine for sorrow.

Nepenthe (nēpenthés) is a fictional[dubious – discuss] medicine for sorrow – a “drug of forgetfulness” mentioned in ancient Greek literature and Greek mythology, depicted as originating in Egypt. The carnivorous plant genus Nepenthes is named after the drug nepenthe.

The word nepenthe first appears in the fourth book of Homer‘s Odyssey:

| ἔνθ᾽ αὖτ᾽ ἄλλ᾽ ἐνόησ᾽ Ἑλένη Διὸς ἐκγεγαυῖα: αὐτίκ᾽ ἄρ᾽ εἰς οἶνον βάλε φάρμακον, ἔνθεν ἔπινον, νηπενθές τ᾽ ἄχολόν τε, κακῶν ἐπίληθον ἁπάντων. | Then Helen, daughter of Zeus, took other counsel. Straightway she cast into the wine of which they were drinking a drug to quiet all pain and strife, and bring forgetfulness of every ill. |

| —Odyssey, Book 4, v. 219–221 |

Figuratively, nepenthe means “that which chases away sorrow”. Literally it means ‘not-sorrow’ or ‘anti-sorrow’: νη-, nē-, i.e. “not” (privative prefix), and πενθές, from πένθος, pénthos, i.e. “grief, sorrow, or mourning”. In the Odyssey, νηπενθές φάρμακον : nēpenthés phármakon (i.e. an anti-sorrow drug) is a magical potion given to Helen by Polydamna, the wife of the noble Egyptian Thon; it quells all sorrows with forgetfulness.

Pliny the Elder and Dioscorides believed nepenthe to be the medicinal herb borage.[citation needed] In modern times prior to the 20th century it was accepted that Indian hemp was the nepenthe. Quoting the passage cited above in his 2015 novel Boussole (Compass), French writer Mathias Énard identifies nepenthe with opium. Likewise, in Forbidden Drugs, Philip Robson writes: “What else could Helen of Troy’s nepenthe have been but opium?” The problem with identifying the drug as opium, however, is that by the time of Homer, it already had a long history of use by the Greeks, whereas nepenthe was something unknown to them.[citation needed]

- νηπενθές. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- Homer (1919). “4.219-221”. Odyssey. Translated by Murray, A.T.; from Homer. Odyssey (in Greek) – via Perseus Project.

- νη-. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project

- πένθος. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- Ripley, George; Dana, Charles A., eds. (1879). “The American cyclopaedia: a popular dictionary of general knowledge”. Internet Archive. New York: D. Appleton. Retrieved 2020-08-10.

- Compass, trans. Charlotte Mandell (NY: New Directions, 2017), pp. 73–74.

- Philip Robson (1999). Forbidden Drugs. Oxford University Press. p. 161. ISBN 978-0-19-262955-5.