JOSEPH PRIESTLEY

1733-1804

English chemist, natural philosopher, separatist theologian, grammarian, multi-subject educator, globetrotter, liberal political theorist and discoverer of oxygen

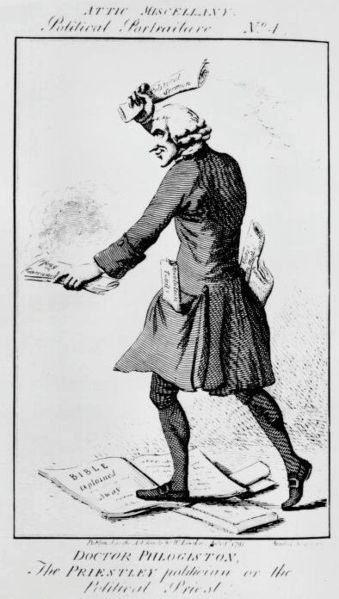

Priestley is credited with the independent discovery of oxygen by the thermal decomposition of mercuric oxide, having isolated it in 1774. During his lifetime, Priestley's considerable scientific reputation rested on his invention of carbonated water, his writings on electricity, and his discovery of several "airs" (gases), the most famous being what Priestley dubbed "dephlogisticated air" (oxygen). Priestley's determination to defend phlogiston theory and to reject what would become the chemical revolution eventually left him isolated within the scientific community.

Priestley's science was integral to his theology, and he consistently tried to fuse Enlightenment rationalism with Christian theism. In his metaphysical texts, Priestley attempted to combine theism, materialism, and determinism, a project that has been called "audacious and original". He believed that a proper understanding of the natural world would promote human progress and eventually bring about the Christian millennium. Priestley, who strongly believed in the free and open exchange of ideas, advocated toleration and equal rights for religious Dissenters, which also led him to help found Unitarianism in England. The controversial nature of Priestley's publications, combined with his outspoken support of the American Revolution and later the French Revolution, aroused public and governmental contempt; eventually forcing him to flee in 1791, first to London and then to the United States, after a mob burned down his Birmingham home and church. He spent his last ten years in Northumberland County, Pennsylvania.

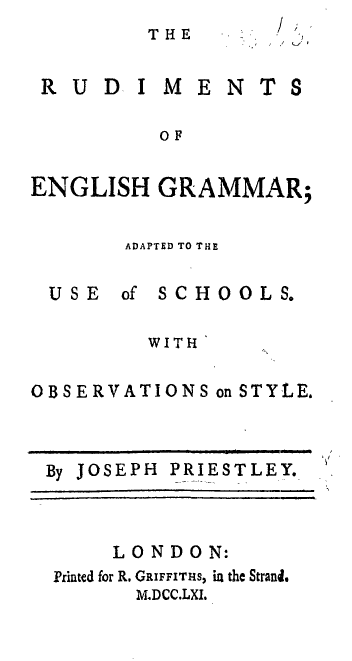

A scholar and teacher throughout his life, Priestley made significant contributions to pedagogy, including the publication of a seminal work on English grammar and books on history; he prepared some of the most influential early timelines. The educational writings were among Priestley's most popular works. Arguably his metaphysical works, however, had the most lasting influence, as now considered primary sources for utilitarianism by philosophers such as Jeremy Bentham, John Stuart Mill, and Herbert Spencer.

- “List of Fellows of the Royal Society 1660 – 2007, K – Z”. royalsociety.org. The Royal Society. Archived from the original on 12 December 2007. Retrieved 1 August 2019.

- “Copley archive winners 1799–1731”. royalsociety.org. The Royal Society. Archived from the original on 11 January 2008. Retrieved 1 August 2019.

- “Priestley” Archived 30 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine: Collins English Dictionary – Complete & Unabridged 2012 Digital Edition.

- Gray & Harrison: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, pp. 351-352

- Isaacson, 2004, pp. 140–141, 289

- Schofield, 1997, p. 142

- H. I. Schlesinger (1950). General Chemistry (4th ed.). p. 134.

- Although Swedish chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele also has strong claims to the discovery, Priestley published his findings first. Scheele discovered it by heating potassium nitrate, mercuric oxide, and many other substances in about 1772.

- “Joseph Priestley, Discoverer of Oxygen National Historic Chemical Landmark”. American Chemical Society. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- Tapper, 10.

- Tapper, 314.

- Van Doren, p. 420

- Schofield, 1997, p. 274

- Gibbs, F. W. Joseph Priestley: Adventurer in Science and Champion of Truth. London: Thomas Nelson and Sons, 1965.

- Graham, Jenny. Revolutionary in Exile: The Emigration of Joseph Priestley to America, 1794–1804. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 85 (1995). ISBN 0-87169-852-8.

- Holt, Anne (1970) [1931]. A life of Joseph Priestley. Westport, Conn., Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-8371-4240-1.

- Jackson, Joe. A World on Fire: A Heretic, an Aristocrat and the Race to Discover Oxygen. New York: Viking, 2005. ISBN 0-670-03434-7.

- Isaacson, Walter (2004). Benjamin Franklin : an American life. New York : Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-6848-07614.

- Johnson, Steven. The Invention of Air: A Story of Science, Faith, Revolution, and the Birth of America. New York: Riverhead, 2008. ISBN 1-59448-852-5.

- Kramnick, Isaac (January 1986). “Eighteenth-Century Science and Radical Social Theory: The Case of Joseph Priestley’s Scientific Liberalism”. Journal of British Studies. Cambridge University Press on behalf of The North American Conference on British Studies. 25 (1): 1–30. doi:10.1086/385852. JSTOR 175609. S2CID 197667044.

- Schofield, Robert E. (1997). The enlightenment of Joseph Priestley : a study of his life and work from 1733 to 1773. University Park, Pa. : Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-0-2710-1662-7.

- Schofield, Robert E. (2004). The Enlightened Joseph Priestley: A Study of His Life and Work from 1773 to 1804. Penn State Press. ISBN 978-0-2710-3246-7.

- Smith, Edgar F. Priestley in America, 1794–1804. Philadelphia: P. Blakiston’s Son and Co., 1920.

- Tapper, Alan. “Joseph Priestley”. Dictionary of Literary Biography 252: British Philosophers 1500–1799. Eds. Philip B. Dematteis and Peter S. Fosl. Detroit: Gale Group, 2002.

- Thorpe, T. E. Joseph Priestley. London: J. M. Dent, 1906.

- Uglow, Jenny. The Lunar Men: Five Friends Whose Curiosity Changed the World. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2002. ISBN 0-374-19440-8.

- Van Doren, Carl (1938). Benjamin Franklin. New York, Garden City Publishing Company.

- Anderson, R. G. W. and Christopher Lawrence. Science, Medicine and Dissent: Joseph Priestley (1733–1804). London: Wellcome Trust, 1987. ISBN 0-901805-28-9.

- Bowers, J. D. Joseph Priestley and English Unitarianism in America. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2007. ISBN 0-271-02951-X.

- Braithwaite, Helen. Romanticism, Publishing and Dissent: Joseph Johnson and the Cause of Liberty. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003. ISBN 0-333-98394-7.

- Conant, J. B., ed. “The Overthrow of the Phlogiston Theory: The Chemical Revolution of 1775–1789”. Harvard Case Histories in Experimental Science. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1950.

- Crook, R. E. A Bibliography of Joseph Priestley. London: Library Association, 1966.

- Crossland, Maurice. “The Image of Science as a Threat: Burke versus Priestley and the ‘Philosophic Revolution'”. British Journal for the History of Science 20 (1987): 277–307.

- Donovan, Arthur. Antoine Lavoisier: Science, Administration and Revolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996. ISBN 0-521-56218-X

- Eshet, Dan. “Rereading Priestley”. History of Science 39.2 (2001): 127–59.

- Fitzpatrick, Martin. “Joseph Priestley and the Cause of Universal Toleration”. The Price-Priestley Newsletter 1 (1977): 3–30.

- Garrett, Clarke. “Joseph Priestley, the Millennium, and the French Revolution”. Journal of the History of Ideas 34.1 (1973): 51–66.

- Fruton, Joseph S. Methods and Styles in the Development of Chemistry. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 2002. ISBN 0-87169-245-7.

- Gray, Henry Colin; Harrison, Brian Howard (2004). Joseph Priestly. Vol. XLV. Oxford; New York : Oxford University Press: Oxford dictionary of national biography. pp. 351–359–.

- Kramnick, Isaac. “Eighteenth-Century Science and Radical Social Theory: The Case of Joseph Priestley’s Scientific Liberalism”. Journal of British Studies 25 (1986): 1–30.

- Kuhn, Thomas. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. 3rd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996. ISBN 0-226-45808-3.

- Haakonssen, Knud, ed. Enlightenment and Religion: Rational Dissent in Eighteenth-Century Britain. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996. ISBN 0-521-56060-8.

- McCann, H. Chemistry Transformed: The Paradigmatic Shift from Phlogiston to Oxygen. Norwood: Alex Publishing, 1978. ISBN 0-89391-004-X.

- McEvoy, John G. “Joseph Priestley, ‘Aerial Philosopher’: Metaphysics and Methodology in Priestley’s Chemical Thought, from 1762 to 1781”. Ambix 25 (1978): 1–55, 93–116, 153–75; 26 (1979): 16–30.

- McEvoy, John G. “Enlightenment and Dissent in Science: Joseph Priestley and the Limits of Theoretical Reasoning”. Enlightenment and Dissent 2 (1983): 47–68.

- McEvoy, John G. “Priestley Responds to Lavoisier’s Nomenclature: Language, Liberty, and Chemistry in the English Enlightenment”. Lavoisier in European Context: Negotiating a New Language for Chemistry. Eds. Bernadette Bensaude-Vincent and Ferdinando Abbri. Canton, MA: Science History Publications, 1995. ISBN 0-88135-189-X.

- McEvoy, John G. and J.E. McGuire. “God and Nature: Priestley’s Way of Rational Dissent”. Historical Studies in the Physical Sciences 6 (1975): 325–404.

- McLachlan, John. Joseph Priestley Man of Science 1733–1804: An Iconography of a Great Yorkshireman. Braunton and Devon: Merlin Books, 1983. ISBN 0-86303-052-1.

- McLachlan, John. “Joseph Priestley and the Study of History”. Transactions of the Unitarian Historical Society 19 (1987–90): 252–63.

- Philip, Mark. “Rational Religion and Political Radicalism”. Enlightenment and Dissent 4 (1985): 35–46.

- Rose, R. B. “The Priestley Riots of 1791”. Past and Present 18 (1960): 68–88.

- Rosenberg, Daniel. Joseph Priestley and the Graphic Invention of Modern Time. Studies in Eighteenth Century Culture 36(1) (2007): pp. 55–103.

- Rutherford, Donald. Leibniz and the Rational Order of Nature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995. ISBN 0-521-46155-3.

- Schaffer, Simon. “Priestley Questions: An Historiographic Survey”. History of Science 22.2 (1984): 151–83.

- Sheps, Arthur. “Joseph Priestley’s Time Charts: The Use and Teaching of History by Rational Dissent in late Eighteenth-Century England”. Lumen 18 (1999): 135–54.

- Watts, R. “Joseph Priestley and Education”. Enlightenment and Dissent 2 (1983): 83–100.

- Lindsay, Jack, ed. Autobiography of Joseph Priestley. Teaneck: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1970. ISBN 0-8386-7831-9.

- Miller, Peter N., ed. Priestley: Political Writings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993. ISBN 0-521-42561-1.

- Passmore, John A., ed. Priestley’s Writings on Philosophy, Science and Politics. New York: Collier Books, 1964.

- Rutt, John T., ed. Collected Theological and Miscellaneous Works of Joseph Priestley. Two vols. London: George Smallfield, 1832.

- Rutt, John T., ed. Life and Correspondence of Joseph Priestley. Two vols. London: George Smallfield, 1831.

- Schofield, Robert E., ed. A Scientific Autobiography of Joseph Priestley (1733–1804): Selected Scientific Correspondence. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1966.

- Links to Priestley’s works online

- “Joseph Priestley”. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- The Joseph Priestley Society

- Joseph Priestley Online Archived 13 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine: Comprehensive site with bibliography, links to related sites, images, information on manuscript collections, and other helpful information.

- Radio 4 program on the discovery of oxygen by the BBC

- Collection of Priestley images Archived 23 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine at the Schoenberg Center for Electronic Text and Image

- Works by Joseph Priestley at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Joseph Priestley at Internet Archive

- Works by Joseph Priestley at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- “Joseph Priestley: Discoverer of Oxygen” at the American Chemical Society

- Joseph Priestley at the Woodrow Wilson National Fellowship Foundation

- Joseph Priestley from the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). “Priestley, Joseph” . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- “Priestley, Joseph” . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- ExplorePAHistory.com

- Poliakoff, Martyn. “Joseph Priestley”. The Periodic Table of Videos. University of Nottingham.

early life

1733–1755

-

Daventry Academy

-

Needham Market and Nantwich (1755–1761)

Warrington Academy (1761–1767)

- Educator and historian

History of electricity

-

Minister of Mill Hill Chapel

-

Religious controversialist

-

Defender of Dissenters and political philosopher

-

Natural philosopher: electricity, Optics, and carbonated water

-

Materialist philosopher

-

Founder of British Unitarianism

-

Experiments and Observations on Different Kinds of Air

-

Discovery of oxygen

-

Chemical Revolution

-

Defender of English Dissenters and French revolutionaries

-

Birmingham riots of 1791

OCCUPATIONS

KNOWN FOR

- Discovery of oxygen and nine other gases including

- Discovery of the carbon cycle

AWARDS

- Fellow of the Royal Society (1766)

- Copley Medal (1772)

Priestley was born in Birstall (near Batley) in the West Riding of Yorkshire, to an established English Dissenting family who did not conform to the Church of England. He was the oldest of six children born to Mary Swift and Jonas Priestley, a finisher of cloth.

Priestley was sent to live with his grandfather around the age of one. He returned home five years later, after his mother died. When his father remarried in 1741, Priestley went to live with his aunt and uncle, the wealthy and childless Sarah (d. 1764) and John Keighley, 3 miles (4.8 km) from Fieldhead.

Priestley was a precocious child – at the age of four, he could flawlessly recite all 107 questions and answers of the Westminster Shorter Catechism – and his aunt sought the best education for him, intending him to enter ministry.

During his youth, Priestley attended local schools, where he learned Greek, Latin, and Hebrew.

Around 1749, Priestley became seriously ill and believed he was dying. Raised as a devout Calvinist, he believed a conversion experience was necessary for salvation, but doubted he had had one. This emotional distress eventually led him to question his theological upbringing, causing him to reject election and to accept universal salvation. As a result, the elders of his home church, the Independent Upper Chapel of Heckmondwike, near Leeds, refused him admission as a full member.

Priestley's illness left him with a permanent stutter and he gave up any thoughts of entering the ministry at that time.

In preparation for joining a relative in trade in Lisbon, he studied French, Italian, and German in addition to Aramaic, and Arabic. He was tutored by the Reverend George Haggerstone, who first introduced him to higher mathematics, natural philosophy, logic, and metaphysics through the works of Isaac Watts, Willem's Gravesande, and John Locke.

DAVENTRY ACADEMY

Priestley eventually decided to return to his theological studies and, in 1752, matriculated at Daventry, a Dissenting academy. Because he was already widely read, Priestley was allowed to omit the first two years of coursework. He continued his intense study; this, together with the liberal atmosphere of the school, shifted his theology further leftward and he became a Rational Dissenter. Abhorring dogma and religious mysticism, Rational Dissenters emphasised rational analysis of the natural world and the Bible.

Priestley later wrote that the book that influenced him the most, save the Bible, was David Hartley's Observations on Man (1749). Hartley's psychological, philosophical, and theological treatise postulated a material theory of mind. Hartley aimed to construct a Christian philosophy in which both religious and moral "facts" could be scientifically proven, a goal that would occupy Priestley for his entire life.

In his third year at Daventry, Priestley committed himself to the ministry, which he described as "the noblest of all professions."

- Gray & Harrison: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, pp. 351-352

- Schofield (1997), 2–12; Uglow, 72; Jackson, 19–25; Gibbs, 1–4; Thorpe, 1–11; Holt, 1–6.

- Schofield (1997), 1, 7–8; Jackson, 25–30; Gibbs, 4; Priestley, Autobiography, 71–73, 123.

- Schofield (1997), 14, 28–29; Uglow, 72; Gibbs, 5; Thorpe, 11–12; Holt, 7–9.

- Schofield (1997), 28–29; Jackson, 30; Gibbs, 5.

- McEvoy (1983), 48–49.

- Qtd. in Jackson, 33. See Schofield (1997), 40–57; Uglow, 73–74; Jackson, 30–34; Gibbs, 5–10; Thorpe, 17–22; Tapper, 314; Holt, 11–14; Garrett, 54.

Bibliography

The most exhaustive biography of Priestley is Robert Schofield’s two-volume work; several older one-volume treatments exist: those of Gibbs, Holt and Thorpe. Graham and Smith focus on Priestley’s life in America and Uglow and Jackson both discuss Priestley’s life in the context of other developments in science.

- Gibbs, F. W. Joseph Priestley: Adventurer in Science and Champion of Truth. London: Thomas Nelson and Sons, 1965.

- Graham, Jenny. Revolutionary in Exile: The Emigration of Joseph Priestley to America, 1794–1804. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 85 (1995). ISBN 0-87169-852-8.

- Holt, Anne (1970) [1931]. A life of Joseph Priestley. Westport, Conn., Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-8371-4240-1.

- Jackson, Joe. A World on Fire: A Heretic, an Aristocrat and the Race to Discover Oxygen. New York: Viking, 2005. ISBN 0-670-03434-7.

- Isaacson, Walter (2004). Benjamin Franklin : an American life. New York : Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-6848-07614.

- Johnson, Steven. The Invention of Air: A Story of Science, Faith, Revolution, and the Birth of America. New York: Riverhead, 2008. ISBN 1-59448-852-5.

- Kramnick, Isaac (January 1986). “Eighteenth-Century Science and Radical Social Theory: The Case of Joseph Priestley’s Scientific Liberalism”. Journal of British Studies. Cambridge University Press on behalf of The North American Conference on British Studies. 25 (1): 1–30. doi:10.1086/385852. JSTOR 175609. S2CID 197667044.

- Schofield, Robert E. (1997). The enlightenment of Joseph Priestley : a study of his life and work from 1733 to 1773. University Park, Pa. : Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-0-2710-1662-7.

- Schofield, Robert E. (2004). The Enlightened Joseph Priestley: A Study of His Life and Work from 1773 to 1804. Penn State Press. ISBN 978-0-2710-3246-7.

- Smith, Edgar F. Priestley in America, 1794–1804. Philadelphia: P. Blakiston’s Son and Co., 1920.

- Tapper, Alan. “Joseph Priestley”. Dictionary of Literary Biography 252: British Philosophers 1500–1799. Eds. Philip B. Dematteis and Peter S. Fosl. Detroit: Gale Group, 2002.

- Thorpe, T. E. Joseph Priestley. London: J. M. Dent, 1906.

- Uglow, Jenny. The Lunar Men: Five Friends Whose Curiosity Changed the World. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2002. ISBN 0-374-19440-8.

- Van Doren, Carl (1938). Benjamin Franklin. New York, Garden City Publishing Company.

Secondary materials

- Anderson, R. G. W. and Christopher Lawrence. Science, Medicine and Dissent: Joseph Priestley (1733–1804). London: Wellcome Trust, 1987. ISBN 0-901805-28-9.

- Bowers, J. D. Joseph Priestley and English Unitarianism in America. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2007. ISBN 0-271-02951-X.

- Braithwaite, Helen. Romanticism, Publishing and Dissent: Joseph Johnson and the Cause of Liberty. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003. ISBN 0-333-98394-7.

- Conant, J. B., ed. “The Overthrow of the Phlogiston Theory: The Chemical Revolution of 1775–1789”. Harvard Case Histories in Experimental Science. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1950.

- Crook, R. E. A Bibliography of Joseph Priestley. London: Library Association, 1966.

- Crossland, Maurice. “The Image of Science as a Threat: Burke versus Priestley and the ‘Philosophic Revolution'”. British Journal for the History of Science 20 (1987): 277–307.

- Donovan, Arthur. Antoine Lavoisier: Science, Administration and Revolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996. ISBN 0-521-56218-X

- Eshet, Dan. “Rereading Priestley”. History of Science 39.2 (2001): 127–59.

- Fitzpatrick, Martin. “Joseph Priestley and the Cause of Universal Toleration”. The Price-Priestley Newsletter 1 (1977): 3–30.

- Garrett, Clarke. “Joseph Priestley, the Millennium, and the French Revolution”. Journal of the History of Ideas 34.1 (1973): 51–66.

- Fruton, Joseph S. Methods and Styles in the Development of Chemistry. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 2002. ISBN 0-87169-245-7.

- Gray, Henry Colin; Harrison, Brian Howard (2004). Joseph Priestly. Vol. XLV. Oxford; New York : Oxford University Press: Oxford dictionary of national biography. pp. 351–359–.

- Kramnick, Isaac. “Eighteenth-Century Science and Radical Social Theory: The Case of Joseph Priestley’s Scientific Liberalism”. Journal of British Studies 25 (1986): 1–30.

- Kuhn, Thomas. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. 3rd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996. ISBN 0-226-45808-3.

- Haakonssen, Knud, ed. Enlightenment and Religion: Rational Dissent in Eighteenth-Century Britain. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996. ISBN 0-521-56060-8.

- McCann, H. Chemistry Transformed: The Paradigmatic Shift from Phlogiston to Oxygen. Norwood: Alex Publishing, 1978. ISBN 0-89391-004-X.

- McEvoy, John G. “Joseph Priestley, ‘Aerial Philosopher’: Metaphysics and Methodology in Priestley’s Chemical Thought, from 1762 to 1781”. Ambix 25 (1978): 1–55, 93–116, 153–75; 26 (1979): 16–30.

- McEvoy, John G. “Enlightenment and Dissent in Science: Joseph Priestley and the Limits of Theoretical Reasoning”. Enlightenment and Dissent 2 (1983): 47–68.

- McEvoy, John G. “Priestley Responds to Lavoisier’s Nomenclature: Language, Liberty, and Chemistry in the English Enlightenment”. Lavoisier in European Context: Negotiating a New Language for Chemistry. Eds. Bernadette Bensaude-Vincent and Ferdinando Abbri. Canton, MA: Science History Publications, 1995. ISBN 0-88135-189-X.

- McEvoy, John G. and J.E. McGuire. “God and Nature: Priestley’s Way of Rational Dissent”. Historical Studies in the Physical Sciences 6 (1975): 325–404.

- McLachlan, John. Joseph Priestley Man of Science 1733–1804: An Iconography of a Great Yorkshireman. Braunton and Devon: Merlin Books, 1983. ISBN 0-86303-052-1.

- McLachlan, John. “Joseph Priestley and the Study of History”. Transactions of the Unitarian Historical Society 19 (1987–90): 252–63.

- Philip, Mark. “Rational Religion and Political Radicalism”. Enlightenment and Dissent 4 (1985): 35–46.

- Rose, R. B. “The Priestley Riots of 1791”. Past and Present 18 (1960): 68–88.

- Rosenberg, Daniel. Joseph Priestley and the Graphic Invention of Modern Time. Studies in Eighteenth Century Culture 36(1) (2007): pp. 55–103.

- Rutherford, Donald. Leibniz and the Rational Order of Nature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995. ISBN 0-521-46155-3.

- Schaffer, Simon. “Priestley Questions: An Historiographic Survey”. History of Science 22.2 (1984): 151–83.

- Sheps, Arthur. “Joseph Priestley’s Time Charts: The Use and Teaching of History by Rational Dissent in late Eighteenth-Century England”. Lumen 18 (1999): 135–54.

- Watts, R. “Joseph Priestley and Education”. Enlightenment and Dissent 2 (1983): 83–100.

Primary materials

- Lindsay, Jack, ed. Autobiography of Joseph Priestley. Teaneck: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1970. ISBN 0-8386-7831-9.

- Miller, Peter N., ed. Priestley: Political Writings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993. ISBN 0-521-42561-1.

- Passmore, John A., ed. Priestley’s Writings on Philosophy, Science and Politics. New York: Collier Books, 1964.

- Rutt, John T., ed. Collected Theological and Miscellaneous Works of Joseph Priestley. Two vols. London: George Smallfield, 1832.

- Rutt, John T., ed. Life and Correspondence of Joseph Priestley. Two vols. London: George Smallfield, 1831.

- Schofield, Robert E., ed. A Scientific Autobiography of Joseph Priestley (1733–1804): Selected Scientific Correspondence. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1966.

External links

- Links to Priestley’s works online

- “Joseph Priestley”. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- The Joseph Priestley Society

- Joseph Priestley Online Archived 13 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine: Comprehensive site with bibliography, links to related sites, images, information on manuscript collections, and other helpful information.

- Radio 4 program on the discovery of oxygen by the BBC

- Collection of Priestley images Archived 23 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine at the Schoenberg Center for Electronic Text and Image

- Works by Joseph Priestley at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Joseph Priestley at Internet Archive

- Works by Joseph Priestley at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

Short online biographies

- “Joseph Priestley: Discoverer of Oxygen” at the American Chemical Society

- Joseph Priestley at the Woodrow Wilson National Fellowship Foundation

- Joseph Priestley from the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). “Priestley, Joseph” . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- “Priestley, Joseph” . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- ExplorePAHistory.com

- Poliakoff, Martyn. “Joseph Priestley”. The Periodic Table of Videos. University of Nottingham.

Needham Market and Nantwich

1755 – 1761

-

Daventry Academy

-

Needham Market and Nantwich (1755–1761)

Warrington Academy (1761–1767)

- Educator and historian

History of electricity

-

Minister of Mill Hill Chapel

-

Religious controversialist

-

Defender of Dissenters and political philosopher

-

Natural philosopher: electricity, Optics, and carbonated water

-

Materialist philosopher

-

Founder of British Unitarianism

-

Experiments and Observations on Different Kinds of Air

-

Discovery of oxygen

-

Chemical Revolution

-

Defender of English Dissenters and French revolutionaries

-

Birmingham riots of 1791

BIOGRAPHICAL

Robert Schofield, Priestley's major modern biographer, describes his first "call" in 1755 to the Dissenting parish in Needham Market, Suffolk, as a "mistake" for both Priestley and the congregation. Priestley yearned for urban life and theological debate, whereas Needham Market was a small, rural town with a congregation wedded to tradition. Attendance and donations dropped sharply when they discovered the extent of his heterodoxy. Although Priestley's aunt had promised her support if he became a minister, she refused any further assistance when she realised he was no longer a Calvinist. To earn extra money, Priestley proposed opening a school, but local families informed him that they would refuse to send their children. He also presented a series of scientific lectures titled "Use of the Globes" that was more successful.

Priestley's Daventry friends helped him obtain another position and in 1758 he moved to Nantwich, Cheshire, living at Sweetbriar Hall in the town's Hospital Street; his time there was happier. The congregation cared less about Priestley's heterodoxy and he successfully established a school. Unlike many schoolmasters of the time, Priestley taught his students natural philosophy and even bought scientific instruments for them. Appalled at the quality of the available English grammar books, Priestley wrote his own: The Rudiments of English Grammar (1761). His innovations in the description of English grammar, particularly his efforts to dissociate it from Latin grammar, led 20th-century scholars to describe him as "one of the great grammarians of his time". After the publication of Rudiments and the success of Priestley's school, Warrington Academy offered him a teaching position in 1761.

- Schofield (1997), 62–69.

- Schofield (1997), 62–69; Jackson, 44–47; Gibbs, 10–11; Thorpe, 22–29; Holt, 15–19.

- Priestley, Joseph. The Rudiments of English Grammar; adapted to the use of schools. With observations on style. London: Printed for R. Griffiths, 1761.

- Qtd. in Schofield (1997), 79.

- Schofield (1997), 77–79, 83–85; Uglow, 72; Jackson 49–52; Gibbs, 13–16; Thorpe, 30–32; Holt, 19–23.

- Gibbs, F. W. Joseph Priestley: Adventurer in Science and Champion of Truth. London: Thomas Nelson and Sons, 1965.

- Graham, Jenny. Revolutionary in Exile: The Emigration of Joseph Priestley to America, 1794–1804. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 85 (1995). ISBN 0-87169-852-8.

- Holt, Anne (1970) [1931]. A life of Joseph Priestley. Westport, Conn., Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-8371-4240-1.

- Jackson, Joe. A World on Fire: A Heretic, an Aristocrat and the Race to Discover Oxygen. New York: Viking, 2005. ISBN 0-670-03434-7.

- Isaacson, Walter (2004). Benjamin Franklin : an American life. New York : Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-6848-07614.

- Johnson, Steven. The Invention of Air: A Story of Science, Faith, Revolution, and the Birth of America. New York: Riverhead, 2008. ISBN 1-59448-852-5.

- Kramnick, Isaac (January 1986). “Eighteenth-Century Science and Radical Social Theory: The Case of Joseph Priestley’s Scientific Liberalism”. Journal of British Studies. Cambridge University Press on behalf of The North American Conference on British Studies. 25 (1): 1–30. doi:10.1086/385852. JSTOR 175609. S2CID 197667044.

- Schofield, Robert E. (1997). The enlightenment of Joseph Priestley : a study of his life and work from 1733 to 1773. University Park, Pa. : Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-0-2710-1662-7.

- Schofield, Robert E. (2004). The Enlightened Joseph Priestley: A Study of His Life and Work from 1773 to 1804. Penn State Press. ISBN 978-0-2710-3246-7.

- Smith, Edgar F. Priestley in America, 1794–1804. Philadelphia: P. Blakiston’s Son and Co., 1920.

- Tapper, Alan. “Joseph Priestley”. Dictionary of Literary Biography 252: British Philosophers 1500–1799. Eds. Philip B. Dematteis and Peter S. Fosl. Detroit: Gale Group, 2002.

- Thorpe, T. E. Joseph Priestley. London: J. M. Dent, 1906.

- Uglow, Jenny. The Lunar Men: Five Friends Whose Curiosity Changed the World. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2002. ISBN 0-374-19440-8.

- Van Doren, Carl (1938). Benjamin Franklin. New York, Garden City Publishing Company.

- Anderson, R. G. W. and Christopher Lawrence. Science, Medicine and Dissent: Joseph Priestley (1733–1804). London: Wellcome Trust, 1987. ISBN 0-901805-28-9.

- Bowers, J. D. Joseph Priestley and English Unitarianism in America. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2007. ISBN 0-271-02951-X.

- Braithwaite, Helen. Romanticism, Publishing and Dissent: Joseph Johnson and the Cause of Liberty. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003. ISBN 0-333-98394-7.

- Conant, J. B., ed. “The Overthrow of the Phlogiston Theory: The Chemical Revolution of 1775–1789”. Harvard Case Histories in Experimental Science. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1950.

- Crook, R. E. A Bibliography of Joseph Priestley. London: Library Association, 1966.

- Crossland, Maurice. “The Image of Science as a Threat: Burke versus Priestley and the ‘Philosophic Revolution'”. British Journal for the History of Science 20 (1987): 277–307.

- Donovan, Arthur. Antoine Lavoisier: Science, Administration and Revolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996. ISBN 0-521-56218-X

- Eshet, Dan. “Rereading Priestley”. History of Science 39.2 (2001): 127–59.

- Fitzpatrick, Martin. “Joseph Priestley and the Cause of Universal Toleration”. The Price-Priestley Newsletter 1 (1977): 3–30.

- Garrett, Clarke. “Joseph Priestley, the Millennium, and the French Revolution”. Journal of the History of Ideas 34.1 (1973): 51–66.

- Fruton, Joseph S. Methods and Styles in the Development of Chemistry. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 2002. ISBN 0-87169-245-7.

- Gray, Henry Colin; Harrison, Brian Howard (2004). Joseph Priestly. Vol. XLV. Oxford; New York : Oxford University Press: Oxford dictionary of national biography. pp. 351–359–.

- Kramnick, Isaac. “Eighteenth-Century Science and Radical Social Theory: The Case of Joseph Priestley’s Scientific Liberalism”. Journal of British Studies 25 (1986): 1–30.

- Kuhn, Thomas. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. 3rd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996. ISBN 0-226-45808-3.

- Haakonssen, Knud, ed. Enlightenment and Religion: Rational Dissent in Eighteenth-Century Britain. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996. ISBN 0-521-56060-8.

- McCann, H. Chemistry Transformed: The Paradigmatic Shift from Phlogiston to Oxygen. Norwood: Alex Publishing, 1978. ISBN 0-89391-004-X.

- McEvoy, John G. “Joseph Priestley, ‘Aerial Philosopher’: Metaphysics and Methodology in Priestley’s Chemical Thought, from 1762 to 1781”. Ambix 25 (1978): 1–55, 93–116, 153–75; 26 (1979): 16–30.

- McEvoy, John G. “Enlightenment and Dissent in Science: Joseph Priestley and the Limits of Theoretical Reasoning”. Enlightenment and Dissent 2 (1983): 47–68.

- McEvoy, John G. “Priestley Responds to Lavoisier’s Nomenclature: Language, Liberty, and Chemistry in the English Enlightenment”. Lavoisier in European Context: Negotiating a New Language for Chemistry. Eds. Bernadette Bensaude-Vincent and Ferdinando Abbri. Canton, MA: Science History Publications, 1995. ISBN 0-88135-189-X.

- McEvoy, John G. and J.E. McGuire. “God and Nature: Priestley’s Way of Rational Dissent”. Historical Studies in the Physical Sciences 6 (1975): 325–404.

- McLachlan, John. Joseph Priestley Man of Science 1733–1804: An Iconography of a Great Yorkshireman. Braunton and Devon: Merlin Books, 1983. ISBN 0-86303-052-1.

- McLachlan, John. “Joseph Priestley and the Study of History”. Transactions of the Unitarian Historical Society 19 (1987–90): 252–63.

- Philip, Mark. “Rational Religion and Political Radicalism”. Enlightenment and Dissent 4 (1985): 35–46.

- Rose, R. B. “The Priestley Riots of 1791”. Past and Present 18 (1960): 68–88.

- Rosenberg, Daniel. Joseph Priestley and the Graphic Invention of Modern Time. Studies in Eighteenth Century Culture 36(1) (2007): pp. 55–103.

- Rutherford, Donald. Leibniz and the Rational Order of Nature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995. ISBN 0-521-46155-3.

- Schaffer, Simon. “Priestley Questions: An Historiographic Survey”. History of Science 22.2 (1984): 151–83.

- Sheps, Arthur. “Joseph Priestley’s Time Charts: The Use and Teaching of History by Rational Dissent in late Eighteenth-Century England”. Lumen 18 (1999): 135–54.

- Watts, R. “Joseph Priestley and Education”. Enlightenment and Dissent 2 (1983): 83–100.

- Lindsay, Jack, ed. Autobiography of Joseph Priestley. Teaneck: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1970. ISBN 0-8386-7831-9.

- Miller, Peter N., ed. Priestley: Political Writings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993. ISBN 0-521-42561-1.

- Passmore, John A., ed. Priestley’s Writings on Philosophy, Science and Politics. New York: Collier Books, 1964.

- Rutt, John T., ed. Collected Theological and Miscellaneous Works of Joseph Priestley. Two vols. London: George Smallfield, 1832.

- Rutt, John T., ed. Life and Correspondence of Joseph Priestley. Two vols. London: George Smallfield, 1831.

- Schofield, Robert E., ed. A Scientific Autobiography of Joseph Priestley (1733–1804): Selected Scientific Correspondence. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1966.

- Links to Priestley’s works online

- “Joseph Priestley”. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- The Joseph Priestley Society

- Joseph Priestley Online Archived 13 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine: Comprehensive site with bibliography, links to related sites, images, information on manuscript collections, and other helpful information.

- Radio 4 program on the discovery of oxygen by the BBC

- Collection of Priestley images Archived 23 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine at the Schoenberg Center for Electronic Text and Image

- Works by Joseph Priestley at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Joseph Priestley at Internet Archive

- Works by Joseph Priestley at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- “Joseph Priestley: Discoverer of Oxygen” at the American Chemical Society

- Joseph Priestley at the Woodrow Wilson National Fellowship Foundation

- Joseph Priestley from the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). “Priestley, Joseph” . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- “Priestley, Joseph” . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- ExplorePAHistory.com

- Poliakoff, Martyn. “Joseph Priestley”. The Periodic Table of Videos. University of Nottingham.

warrington academy

1761 – 1767

-

Daventry Academy

-

Needham Market and Nantwich (1755–1761)

Warrington Academy (1761–1767)

- Educator and historian

History of electricity

-

Minister of Mill Hill Chapel

-

Religious controversialist

-

Defender of Dissenters and political philosopher

-

Natural philosopher: electricity, Optics, and carbonated water

-

Materialist philosopher

-

Founder of British Unitarianism

-

Experiments and Observations on Different Kinds of Air

-

Discovery of oxygen

-

Chemical Revolution

-

Defender of English Dissenters and French revolutionaries

-

Birmingham riots of 1791

In 1761, Priestley moved to Warrington in Cheshire and assumed the post of tutor of modern languages and rhetoric at the town's Dissenting academy although he would have preferred to teach mathematics and natural philosophy. He fit in well at Warrington and made friends quickly. These included the doctor and writer John Aikin, his sister the children's author Anna Laetitia Aikin, and the potter and businessman Josiah Wedgwood. Wedgwood met Priestley in 1762, after a fall from his horse. Wedgwood and Priestley met rarely, but exchanged letters, advice on chemistry, and laboratory equipment. Wedgwood eventually created a medallion of Priestley in cream-on-blue jasperware.

On 23 June 1762, Priestley married Mary Wilkinson of Wrexham. Of his marriage, Priestley wrote:

This proved a very suitable and happy connexion, my wife being a woman of an excellent understanding, much improved by reading, of great fortitude and strength of mind, and of a temper in the highest degree affectionate and generous; feeling strongly for others, and little for herself. Also, greatly excelling in every thing relating to household affairs, she entirely relieved me of all concern of that kind, which allowed me to give all my time to the prosecution of my studies, and the other duties of my station.

On 17 April 1763, they had a daughter, whom they named Sarah after Priestley's aunt.

educator and historian

All of the books Priestley published while at Warrington emphasised the study of history; Priestley considered it essential for worldly success as well as religious growth. He wrote histories of science and Christianity in an effort to reveal the progress of humanity and, paradoxically, the loss of a pure, "primitive Christianity"

In his Essay on a Course of Liberal Education for Civil and Active Life (1765), Lectures on History and General Policy (1788), and other works, Priestley argued that the education of the young should anticipate their future practical needs. This principle of utility guided his unconventional curricular choices for Warrington's aspiring middle-class students. He recommended modern languages instead of classical languages and modern rather than ancient history. Priestley's lectures on history were particularly revolutionary; he narrated a providentialist and naturalist account of history, arguing that the study of history furthered the comprehension of God's natural laws. Furthermore, his millennial perspective was closely tied to his optimism regarding scientific progress and the improvement of humanity. He believed that each age would improve upon the previous and that the study of history allowed people to perceive and to advance this progress. Since the study of history was a moral imperative for Priestley, he also promoted the education of middle-class women, which was unusual at the time. Some scholars of education have described Priestley as the most important English writer on education between the 17th-century John Locke and the 19th-century Herbert Spencer. Lectures on History was well received and was employed by many educational institutions, such as New College at Hackney, Brown, Princeton, Yale, and Cambridge. Priestley designed two Charts to serve as visual study aids for his Lectures. These charts are in fact timelines; they have been described as the most influential timelines published in the 18th century. Both were popular for decades, and the trustees of Warrington were so impressed with Priestley's lectures and charts that they arranged for the University of Edinburgh to grant him a Doctor of Law degree in 1764. During this period Priestley also regularly delivered lectures on rhetoric that were later published in 1777 as A Course of Lectures on Oratory and Criticism.

history of electricity

The intellectually stimulating atmosphere of Warrington, often called the "Athens of the North" (of England) during the 18th century, encouraged Priestley's growing interest in natural philosophy. He gave lectures on anatomy and performed experiments regarding temperature with another tutor at Warrington, his friend John Seddon. Despite Priestley's busy teaching schedule, he decided to write a history of electricity. Friends introduced him to the major experimenters in the field in Britain—John Canton, William Watson, Timothy Lane, and the visiting Benjamin Franklin who encouraged Priestley to perform the experiments he wanted to include in his history. Priestley also consulted with Franklin during the latter's kite experiments. In the process of replicating others' experiments, Priestley became intrigued by unanswered questions and was prompted to undertake experiments of his own design. (Impressed with his Charts and the manuscript of his history of electricity, Canton, Franklin, Watson, and Richard Price nominated Priestley for a fellowship in the Royal Society; he was accepted in 1766.)

In 1767, the 700-page The History and Present State of Electricity was published to positive reviews. The first half of the text is a history of the study of electricity to 1766; the second and more influential half is a description of contemporary theories about electricity and suggestions for future research. The volume also contains extensive comments on Priestley's views that scientific inquiries be presented with all reasoning in one's discovery path, including false leads and mistakes. He contrasted his narrative approach with Newton's analytical proof-like approach which did not facilitate future researchers to continue the inquiry. Priestley reported some of his own discoveries in the second section, such as the conductivity of charcoal and other substances and the continuum between conductors and non-conductors. This discovery overturned what he described as "one of the earliest and universally received maxims of electricity", that only water and metals could conduct electricity. This and other experiments on the electrical properties of materials and on the electrical effects of chemical transformations demonstrated Priestley's early and ongoing interest in the relationship between chemical substances and electricity. Based on experiments with charged spheres, Priestley was among the first to propose that electrical force followed an inverse-square law, similar to Newton's law of universal gravitation. He did not generalise or elaborate on this, and the general law was enunciated by French physicist Charles-Augustin de Coulomb in the 1780s.

Priestley's strength as a natural philosopher was qualitative rather than quantitative and his observation of "a current of real air" between two electrified points would later interest Michael Faraday and James Clerk Maxwell as they investigated electromagnetism. Priestley's text became the standard history of electricity for over a century; Alessandro Volta (who later invented the battery), William Herschel (who discovered infrared radiation), and Henry Cavendish (who discovered hydrogen) all relied upon it. Priestley wrote a popular version of the History of Electricity for the general public titled A Familiar Introduction to the Study of Electricity (1768). He marketed the book with his brother Timothy, but unsuccessfully.

- McLachlan, Iconography, 24–26.

- Schofield, Robert E. (2009). Enlightened joseph priestley : a study of his life and work from 1773 to 1804. University Park: Penn State Univ Press. ISBN 978-0-271-03625-0. Retrieved 26 June 2018.

- Meyer, Michal (2018). “Old Friends”. Distillations. 4 (1): 6–9. Retrieved 26 June 2018.

- Bowden, Mary Ellen; Rosner, Lisa, eds. (2005). Joseph Priestley, radical thinker : a catalogue to accompany the exhibit at the Chemical Heritage Foundation commemorating the 200th anniversary of the death of Joseph Priestley, 23 August 2004 to 29 July 2005. Philadelphia, Penns.: Chemical Heritage Foundation. p. 26. ISBN 978-0941901383. Archived from the original on 2 June 2016. Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- Priestley, Autobiography, 87.

- See Thorpe, 33–44 for a description of life at Warrington; Schofield (1997), 89–90, 93–94; Jackson, 54–58; Uglow, 73–75; Thorpe, 47–50; Holt, 27–28.

- Sheps, 135, 149; Holt, 29–30.

- Qtd. in Sheps, 146.

- Priestley, Joseph. Essay on a Course of Liberal Education for Civil and Active Life. London: Printed for C. Henderson under the Royal Exchange; T. Becket and De Hondt in the Strand; and by J. Johnson and Davenport, in Pater-Noster-Row, 1765.

- Thorpe, 52–54; Schofield (1997), 124–25; Watts, 89, 95–97; Sheps, 136.

- Schofield (1997), 121; see also Watts, 92.

- Schofield (2004), 254–59; McLachlan (1987–90), 255–58; Sheps, 138, 141; Kramnick, 12; Holt, 29–33.

- Priestley, Joseph. A Chart of Biography. London: J. Johnson, St. Paul’s Church Yard, 1765 and Joseph Priestley, A Description of a Chart of Biography. Warrington: Printed by William Eyres, 1765 and Joseph Priestley, A New Chart of History. London: Engraved and published for J. Johnson, 1769; A Description of a New Chart of History. London: Printed for J. Johnson, 1770.

- Rosenberg, 57–65 and ff.

- Gibbs, 37; Schofield (1997), 118–19.

- J. Priestley. A Course of Lectures on Oratory and Criticism. London, 1777. Ed. V. M. Bevilacqua & R. Murphy. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1965.

- Schofield (1997), 136–37; Jackson, 57–61.

- Isaacson, 2004, pp. 140–141, 182

- Van Doren, pp. 164–165

- Schofield (1997), 141–42, 152; Jackson, 64; Uglow 75–77; Thorpe, 61–65.

- Schofield (1997), 143–44; Jackson, 65–66; see Schofield (1997), 152 and 231–32 for an analysis of the different editions.

- Priestley, Joseph. The History and Present State of Electricity, with original experiments. London: Printed for J. Dodsley, J. Johnson and T. Cadell, 1767.

- Schofield (1997), 144–56.

- Schofield (1997), 156–57; Gibbs 28–31; see also Thorpe, 64.

- Other early investigators who suspected that the electrical force diminished with distance as the gravitational force did (i.e., as the inverse square of the distance) included Daniel Bernoulli (see: Abel Socin (1760) Acta Helvetia, vol. 4, pp. 224–25.) and Alessandro Volta, both of whom measured the force between plates of a capacitor, and Aepinus. See: J.L. Heilbron, Electricity in the 17th and 18th Centuries: A Study of Early Modern Physics (Los Angeles, California: University of California Press, 1979), pp. 460–62, 464 Archived 14 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine (including footnote 44).

Joseph Priestley, The History and Present State of Electricity, with Original Experiments (London, England: 1767), p. 732 Archived 28 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine: “May we not infer from this experiment, that the attraction of electricity is subject to the same laws with that of gravitation, and is therefore according to the squares of the distances; since it is easily demonstrated, that were the earth in the form of a shell, a body in the inside of it would not be attracted to one side more than another?”

- Coulomb (1785) “Premier mémoire sur l’électricité et le magnétisme,” Histoire de l’Académie Royale des Sciences, pp. 569–577

- Priestley, Joseph. A Familiar Introduction to the Study of Electricity. London: Printed for J. Dodsley; T. Cadell; and J. Johnson, 1768.

- Schofield (1997), 228–30.

Bibliography

The most exhaustive biography of Priestley is Robert Schofield’s two-volume work; several older one-volume treatments exist: those of Gibbs, Holt and Thorpe. Graham and Smith focus on Priestley’s life in America and Uglow and Jackson both discuss Priestley’s life in the context of other developments in science.

- Gibbs, F. W. Joseph Priestley: Adventurer in Science and Champion of Truth. London: Thomas Nelson and Sons, 1965.

- Graham, Jenny. Revolutionary in Exile: The Emigration of Joseph Priestley to America, 1794–1804. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 85 (1995). ISBN 0-87169-852-8.

- Holt, Anne (1970) [1931]. A life of Joseph Priestley. Westport, Conn., Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-8371-4240-1.

- Jackson, Joe. A World on Fire: A Heretic, an Aristocrat and the Race to Discover Oxygen. New York: Viking, 2005. ISBN 0-670-03434-7.

- Isaacson, Walter (2004). Benjamin Franklin : an American life. New York : Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-6848-07614.

- Johnson, Steven. The Invention of Air: A Story of Science, Faith, Revolution, and the Birth of America. New York: Riverhead, 2008. ISBN 1-59448-852-5.

- Kramnick, Isaac (January 1986). “Eighteenth-Century Science and Radical Social Theory: The Case of Joseph Priestley’s Scientific Liberalism”. Journal of British Studies. Cambridge University Press on behalf of The North American Conference on British Studies. 25 (1): 1–30. doi:10.1086/385852. JSTOR 175609. S2CID 197667044.

- Schofield, Robert E. (1997). The enlightenment of Joseph Priestley : a study of his life and work from 1733 to 1773. University Park, Pa. : Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-0-2710-1662-7.

- Schofield, Robert E. (2004). The Enlightened Joseph Priestley: A Study of His Life and Work from 1773 to 1804. Penn State Press. ISBN 978-0-2710-3246-7.

- Smith, Edgar F. Priestley in America, 1794–1804. Philadelphia: P. Blakiston’s Son and Co., 1920.

- Tapper, Alan. “Joseph Priestley”. Dictionary of Literary Biography 252: British Philosophers 1500–1799. Eds. Philip B. Dematteis and Peter S. Fosl. Detroit: Gale Group, 2002.

- Thorpe, T. E. Joseph Priestley. London: J. M. Dent, 1906.

- Uglow, Jenny. The Lunar Men: Five Friends Whose Curiosity Changed the World. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2002. ISBN 0-374-19440-8.

- Van Doren, Carl (1938). Benjamin Franklin. New York, Garden City Publishing Company.

Secondary materials

- Anderson, R. G. W. and Christopher Lawrence. Science, Medicine and Dissent: Joseph Priestley (1733–1804). London: Wellcome Trust, 1987. ISBN 0-901805-28-9.

- Bowers, J. D. Joseph Priestley and English Unitarianism in America. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2007. ISBN 0-271-02951-X.

- Braithwaite, Helen. Romanticism, Publishing and Dissent: Joseph Johnson and the Cause of Liberty. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003. ISBN 0-333-98394-7.

- Conant, J. B., ed. “The Overthrow of the Phlogiston Theory: The Chemical Revolution of 1775–1789”. Harvard Case Histories in Experimental Science. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1950.

- Crook, R. E. A Bibliography of Joseph Priestley. London: Library Association, 1966.

- Crossland, Maurice. “The Image of Science as a Threat: Burke versus Priestley and the ‘Philosophic Revolution'”. British Journal for the History of Science 20 (1987): 277–307.

- Donovan, Arthur. Antoine Lavoisier: Science, Administration and Revolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996. ISBN 0-521-56218-X

- Eshet, Dan. “Rereading Priestley”. History of Science 39.2 (2001): 127–59.

- Fitzpatrick, Martin. “Joseph Priestley and the Cause of Universal Toleration”. The Price-Priestley Newsletter 1 (1977): 3–30.

- Garrett, Clarke. “Joseph Priestley, the Millennium, and the French Revolution”. Journal of the History of Ideas 34.1 (1973): 51–66.

- Fruton, Joseph S. Methods and Styles in the Development of Chemistry. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 2002. ISBN 0-87169-245-7.

- Gray, Henry Colin; Harrison, Brian Howard (2004). Joseph Priestly. Vol. XLV. Oxford; New York : Oxford University Press: Oxford dictionary of national biography. pp. 351–359–.

- Kramnick, Isaac. “Eighteenth-Century Science and Radical Social Theory: The Case of Joseph Priestley’s Scientific Liberalism”. Journal of British Studies 25 (1986): 1–30.

- Kuhn, Thomas. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. 3rd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996. ISBN 0-226-45808-3.

- Haakonssen, Knud, ed. Enlightenment and Religion: Rational Dissent in Eighteenth-Century Britain. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996. ISBN 0-521-56060-8.

- McCann, H. Chemistry Transformed: The Paradigmatic Shift from Phlogiston to Oxygen. Norwood: Alex Publishing, 1978. ISBN 0-89391-004-X.

- McEvoy, John G. “Joseph Priestley, ‘Aerial Philosopher’: Metaphysics and Methodology in Priestley’s Chemical Thought, from 1762 to 1781”. Ambix 25 (1978): 1–55, 93–116, 153–75; 26 (1979): 16–30.

- McEvoy, John G. “Enlightenment and Dissent in Science: Joseph Priestley and the Limits of Theoretical Reasoning”. Enlightenment and Dissent 2 (1983): 47–68.

- McEvoy, John G. “Priestley Responds to Lavoisier’s Nomenclature: Language, Liberty, and Chemistry in the English Enlightenment”. Lavoisier in European Context: Negotiating a New Language for Chemistry. Eds. Bernadette Bensaude-Vincent and Ferdinando Abbri. Canton, MA: Science History Publications, 1995. ISBN 0-88135-189-X.

- McEvoy, John G. and J.E. McGuire. “God and Nature: Priestley’s Way of Rational Dissent”. Historical Studies in the Physical Sciences 6 (1975): 325–404.

- McLachlan, John. Joseph Priestley Man of Science 1733–1804: An Iconography of a Great Yorkshireman. Braunton and Devon: Merlin Books, 1983. ISBN 0-86303-052-1.

- McLachlan, John. “Joseph Priestley and the Study of History”. Transactions of the Unitarian Historical Society 19 (1987–90): 252–63.

- Philip, Mark. “Rational Religion and Political Radicalism”. Enlightenment and Dissent 4 (1985): 35–46.

- Rose, R. B. “The Priestley Riots of 1791”. Past and Present 18 (1960): 68–88.

- Rosenberg, Daniel. Joseph Priestley and the Graphic Invention of Modern Time. Studies in Eighteenth Century Culture 36(1) (2007): pp. 55–103.

- Rutherford, Donald. Leibniz and the Rational Order of Nature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995. ISBN 0-521-46155-3.

- Schaffer, Simon. “Priestley Questions: An Historiographic Survey”. History of Science 22.2 (1984): 151–83.

- Sheps, Arthur. “Joseph Priestley’s Time Charts: The Use and Teaching of History by Rational Dissent in late Eighteenth-Century England”. Lumen 18 (1999): 135–54.

- Watts, R. “Joseph Priestley and Education”. Enlightenment and Dissent 2 (1983): 83–100.

Primary materials

- Lindsay, Jack, ed. Autobiography of Joseph Priestley. Teaneck: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1970. ISBN 0-8386-7831-9.

- Miller, Peter N., ed. Priestley: Political Writings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993. ISBN 0-521-42561-1.

- Passmore, John A., ed. Priestley’s Writings on Philosophy, Science and Politics. New York: Collier Books, 1964.

- Rutt, John T., ed. Collected Theological and Miscellaneous Works of Joseph Priestley. Two vols. London: George Smallfield, 1832.

- Rutt, John T., ed. Life and Correspondence of Joseph Priestley. Two vols. London: George Smallfield, 1831.

- Schofield, Robert E., ed. A Scientific Autobiography of Joseph Priestley (1733–1804): Selected Scientific Correspondence. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1966.

External links

- Links to Priestley’s works online

- “Joseph Priestley”. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- The Joseph Priestley Society

- Joseph Priestley Online Archived 13 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine: Comprehensive site with bibliography, links to related sites, images, information on manuscript collections, and other helpful information.

- Radio 4 program on the discovery of oxygen by the BBC

- Collection of Priestley images Archived 23 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine at the Schoenberg Center for Electronic Text and Image

- Works by Joseph Priestley at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Joseph Priestley at Internet Archive

- Works by Joseph Priestley at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

Short online biographies

- “Joseph Priestley: Discoverer of Oxygen” at the American Chemical Society

- Joseph Priestley at the Woodrow Wilson National Fellowship Foundation

- Joseph Priestley from the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). “Priestley, Joseph” . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- “Priestley, Joseph” . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- ExplorePAHistory.com

- Poliakoff, Martyn. “Joseph Priestley”. The Periodic Table of Videos. University of Nottingham.

leeds

1767 – 1773

"father of the soft drink" and a copley medal

-

Daventry Academy

-

Needham Market and Nantwich (1755–1761)

Warrington Academy (1761–1767)

- Educator and historian

History of electricity

-

Minister of Mill Hill Chapel

-

Religious controversialist

-

Defender of Dissenters and political philosopher

-

Natural philosopher: electricity, Optics, and carbonated water

-

Materialist philosopher

-

Founder of British Unitarianism

-

Experiments and Observations on Different Kinds of Air

-

Discovery of oxygen

-

Chemical Revolution

-

Defender of English Dissenters and French revolutionaries

-

Birmingham riots of 1791

Perhaps prompted by Mary Priestley's ill health, or financial problems, or a desire to prove himself to the community that had rejected him in his childhood, Priestley moved with his family from Warrington to Leeds in 1767, and he became Mill Hill Chapel's minister. Two sons were born to the Priestleys in Leeds: Joseph junior on 24 July 1768 and William three years later. Theophilus Lindsey, a rector at Catterick, Yorkshire, became one of Priestley's few friends in Leeds, of whom he wrote: "I never chose to publish any thing of moment relating to theology, without consulting him." Although Priestley had extended family living around Leeds, it does not appear that they communicated. Schofield conjectures that they considered him a heretic. Each year Priestley travelled to London to consult with his close friend and publisher, Joseph Johnson, and to attend meetings of the Royal Society.

Minister of Mill Hill Chapel

When Priestley became its minister, Mill Hill Chapel was one of the oldest and most respected Dissenting congregations in England; however, during the early 18th century the congregation had fractured along doctrinal lines, and was losing members to the charismatic Methodist movement. Priestley believed that by educating the young, he could strengthen the bonds of the congregation.

In his three-volume Institutes of Natural and Revealed Religion (1772–74), Priestley outlined his theories of religious instruction. More importantly, he laid out his belief in Socinianism. The doctrines he explicated would become the standards for Unitarians in Britain. This work marked a change in Priestley's theological thinking that is critical to understanding his later writings—it paved the way for his materialism and necessitarianism (the belief that a divine being acts in accordance with necessary metaphysical laws).

Priestley's major argument in the Institutes was that the only revealed religious truths that could be accepted were those that matched one's experience of the natural world. Because his views of religion were deeply tied to his understanding of nature, the text's theism rested on the argument from design. The Institutes shocked and appalled many readers, primarily because it challenged basic Christian orthodoxies, such as the divinity of Christ and the miracle of the Virgin Birth. Methodists in Leeds penned a hymn asking God to "the Unitarian fiend expel / And chase his doctrine back to Hell." Priestley wanted to return Christianity to its "primitive" or "pure" form by eliminating the "corruptions" which had accumulated over the centuries. The fourth part of the Institutes, An History of the Corruptions of Christianity, became so long that he was forced to issue it separately in 1782. Priestley believed that the Corruptions was "the most valuable" work he ever published. In demanding that his readers apply the logic of the emerging sciences and comparative history to the Bible and Christianity, he alienated religious and scientific readers alike—scientific readers did not appreciate seeing science used in the defence of religion and religious readers dismissed the application of science to religion.

religious controversialist

Priestley engaged in numerous political and religious pamphlet wars. According to Schofield, "he entered each controversy with a cheerful conviction that he was right, while most of his opponents were convinced, from the outset, that he was willfully and maliciously wrong. He was able, then, to contrast his sweet reasonableness to their personal rancor", but as Schofield points out Priestley rarely altered his opinion as a result of these debates. While at Leeds he wrote controversial pamphlets on the Lord's Supper and on Calvinist doctrine; thousands of copies were published, making them some of Priestley's most widely read works.

Priestley founded the Theological Repository in 1768, a journal committed to the open and rational inquiry of theological questions. Although he promised to print any contribution, only like-minded authors submitted articles. He was therefore obliged to provide much of the journal's content himself (this material became the basis for many of his later theological and metaphysical works). After only a few years, due to a lack of funds, he was forced to cease publishing the journal. He revived it in 1784 with similar results.

Defender of Dissenters and political philosopher

Many of Priestley's political writings supported the repeal of the Test and Corporation Acts, which restricted the rights of Dissenters. They could not hold political office, serve in the armed forces, or attend Oxford and Cambridge unless they subscribed to the Thirty-nine Articles of the Church of England. Dissenters repeatedly petitioned Parliament to repeal the Acts, arguing that they were being treated as second-class citizens.

Priestley's friends, particularly other Rational Dissenters, urged him to publish a work on the injustices experienced by Dissenters; the result was his Essay on the First Principles of Government (1768). An early work of modern liberal political theory and Priestley's most thorough treatment of the subject, it—unusually for the time—distinguished political rights from civil rights with precision and argued for expansive civil rights. Priestley identified separate private and public spheres, contending that the government should have control only over the public sphere. Education and religion, in particular, he maintained, were matters of private conscience and should not be administered by the state. Priestley's later radicalism emerged from his belief that the British government was infringing upon these individual freedoms.

Priestley also defended the rights of Dissenters against the attacks of William Blackstone, an eminent legal theorist, whose Commentaries on the Laws of England (1765–69) had become the standard legal guide. Blackstone's book stated that dissent from the Church of England was a crime and that Dissenters could not be loyal subjects. Furious, Priestley lashed out with his Remarks on Dr. Blackstone's Commentaries (1769), correcting Blackstone's interpretation of the law, his grammar (a highly politicised subject at the time), and history. Blackstone, chastened, altered subsequent editions of his Commentaries: he rephrased the offending passages and removed the sections claiming that Dissenters could not be loyal subjects, but he retained his description of Dissent as a crime.

Natural philosopher: electricity, Optics, and carbonated water

Although Priestley claimed that natural philosophy was only a hobby, he took it seriously. In his History of Electricity, he described the scientist as promoting the "security and happiness of mankind". Priestley's science was eminently practical and he rarely concerned himself with theoretical questions; his model was his close friend, Benjamin Franklin. When he moved to Leeds, Priestley continued his electrical and chemical experiments (the latter aided by a steady supply of carbon dioxide from a neighbouring brewery). Between 1767 and 1770, he presented five papers to the Royal Society from these initial experiments; the first four papers explored coronal discharges and other phenomena related to electrical discharge, while the fifth reported on the conductivity of charcoals from different sources. His subsequent experimental work focused on chemistry and pneumatics.

Priestley published the first volume of his projected history of experimental philosophy, The History and Present State of Discoveries Relating to Vision, Light and Colours (referred to as his Optics), in 1772. He paid careful attention to the history of optics and presented excellent explanations of early optics experiments, but his mathematical deficiencies caused him to dismiss several important contemporary theories. He followed the (corpuscular) particle theory of light, influenced by the works of Reverend John Rowning and others. Furthermore, he did not include any of the practical sections that had made his History of Electricity so useful to practising natural philosophers. Unlike his History of Electricity, it was not popular and had only one edition, although it was the only English book on the topic for 150 years. The hastily written text sold poorly; the cost of researching, writing, and publishing the Optics convinced Priestley to abandon his history of experimental philosophy.

Priestley was considered for the position of astronomer on James Cook's second voyage to the South Seas, but was not chosen. Still, he contributed in a small way to the voyage: he provided the crew with a method for making carbonated water, which he erroneously speculated might be a cure for scurvy. He then published a pamphlet with Directions for Impregnating Water with Fixed Air (1772). Priestley did not exploit the commercial potential of carbonated water, but others such as J. J. Schweppe made fortunes from it. For his discovery of carbonated water Priestley has been labelled "the father of the soft drink", with the beverage company Schweppes regarding him as "the father of our industry". In 1773, the Royal Society recognised Priestley's achievements in natural philosophy by awarding him the Copley Medal.

Priestley's friends wanted to find him a more financially secure position. In 1772, prompted by Richard Price and Benjamin Franklin, Lord Shelburne wrote to Priestley asking him to direct the education of his children and to act as his general assistant. Although Priestley was reluctant to sacrifice his ministry, he accepted the position, resigning from Mill Hill Chapel on 20 December 1772, and preaching his last sermon on 16 May 1773.

- Schofield (1997), 162–64.

- Priestley, Autobiography, 98; see also Schofield (1997), 163.

- Schofield (1997), 162, note 7.

- Schofield, (1997), 158, 164; Gibbs, 37; Uglow, 170.

- Schofield (1997), 165–69; Holt, 42–43.

- Schofield (1997), 170–71; Gibbs, 37; Watts, 93–94; Holt, 44.

- Priestley. Institutes of Natural and Revealed Religion. London: Printed for J. Johnson, Vol. I, 1772, Vol. II, 1773, Vol. III, 1774.

- Miller, xvi; Schofield (1997), 172.

- Schofield (1997), 174; Uglow, 169; Tapper, 315; Holt, 44.

- Qtd. in Jackson, 102.

- McLachlan (1987–90), 261; Gibbs, 38; Jackson, 102; Uglow, 169.

- Schofield (1997), 181.

- See Schofield (1997), 181–88 for analysis of these two controversies.

- See Schofield (1997), 193–201 for an analysis of the journal; Uglow, 169; Holt, 53–55.

- See Schofield (2004), 202–7 for an analysis of Priestley’s contributions.

- Schofield (1997), 207.

- Schofield (1997), 202–05; Holt, 56–64.

- Priestley, Joseph. Essay on the First Principles of Government; and on the nature of political, civil, and religious liberty. London: Printed for J. Dodsley; T. Cadell; and J. Johnson, 1768.

- Gibbs, 39–43; Uglow, 169; Garrett, 17; Tapper, 315; Holt, 34–37; Philip (1985); Miller, xiv.

- Priestley, Joseph. Remarks on some paragraphs in the fourth volume of Dr. Blackstone’s Commentaries on the laws of England, relating to the Dissenters. London: Printed for J. Johnson and J. Payne, 1769.

- Schofield (1997), 214–16; Gibbs, 43; Holt, 48–49.

- Qtd. in Kramnick, 8.

- Kramnick, 1981, p. 10

- Schofield (1997), 227, 232–38; see also Gibbs, 47; Kramnick, 9–10.

- Priestley, Joseph. Proposals for printing by subscription, The history and present state of discoveries relating to vision, light, and colours. Leeds: n.p., 1771.

- Moura, Breno (2018). “Newtonian Optics and the Historiography of Light in the 18th Century: A critical Analysis of Joseph Priestley’s The History of Optics”. Transversal: International Journal for the Historiography of Science (5). doi:10.24117/2526-2270.2018.i5.12. ISSN 2526-2270. S2CID 239593348.

- Schofield (1997), 240–49; Gibbs, 50–55; Uglow, 134.

- Priestley, Joseph. Directions for impregnating water with fixed air; in order to communicate to it the peculiar spirit and virtues of Pyrmont water, and other mineral waters of a similar nature. London: Printed for J. Johnson, 1772.

- Schofield (1997), 256–57; Gibbs, 57–59; Thorpe, 76–79; Uglow, 134–36; 232–34.

- Schils, René (2011). How James Watt Invented the Copier: Forgotten Inventions of Our Great Scientists. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 36.

- LaMoreaux, Philip E. (2012). Springs and Bottled Waters of the World: Ancient History, Source, Occurrence, Quality and Use. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 135.

- Schofield (1997), 251–55; see Holt, 64; Gibbs, 55–56; and Thorpe, 80–81, for the traditional account of this story.

- Schofield (1997), 270–71; Jackson, 120–22; Gibbs, 84–86: Uglow, 239–40; Holt, 64–65.

Bibliography

The most exhaustive biography of Priestley is Robert Schofield’s two-volume work; several older one-volume treatments exist: those of Gibbs, Holt and Thorpe. Graham and Smith focus on Priestley’s life in America and Uglow and Jackson both discuss Priestley’s life in the context of other developments in science.

- Gibbs, F. W. Joseph Priestley: Adventurer in Science and Champion of Truth. London: Thomas Nelson and Sons, 1965.

- Graham, Jenny. Revolutionary in Exile: The Emigration of Joseph Priestley to America, 1794–1804. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 85 (1995). ISBN 0-87169-852-8.

- Holt, Anne (1970) [1931]. A life of Joseph Priestley. Westport, Conn., Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-8371-4240-1.

- Jackson, Joe. A World on Fire: A Heretic, an Aristocrat and the Race to Discover Oxygen. New York: Viking, 2005. ISBN 0-670-03434-7.

- Isaacson, Walter (2004). Benjamin Franklin : an American life. New York : Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-6848-07614.

- Johnson, Steven. The Invention of Air: A Story of Science, Faith, Revolution, and the Birth of America. New York: Riverhead, 2008. ISBN 1-59448-852-5.

- Kramnick, Isaac (January 1986). “Eighteenth-Century Science and Radical Social Theory: The Case of Joseph Priestley’s Scientific Liberalism”. Journal of British Studies. Cambridge University Press on behalf of The North American Conference on British Studies. 25 (1): 1–30. doi:10.1086/385852. JSTOR 175609. S2CID 197667044.

- Schofield, Robert E. (1997). The enlightenment of Joseph Priestley : a study of his life and work from 1733 to 1773. University Park, Pa. : Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-0-2710-1662-7.

- Schofield, Robert E. (2004). The Enlightened Joseph Priestley: A Study of His Life and Work from 1773 to 1804. Penn State Press. ISBN 978-0-2710-3246-7.

- Smith, Edgar F. Priestley in America, 1794–1804. Philadelphia: P. Blakiston’s Son and Co., 1920.

- Tapper, Alan. “Joseph Priestley”. Dictionary of Literary Biography 252: British Philosophers 1500–1799. Eds. Philip B. Dematteis and Peter S. Fosl. Detroit: Gale Group, 2002.

- Thorpe, T. E. Joseph Priestley. London: J. M. Dent, 1906.

- Uglow, Jenny. The Lunar Men: Five Friends Whose Curiosity Changed the World. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2002. ISBN 0-374-19440-8.

- Van Doren, Carl (1938). Benjamin Franklin. New York, Garden City Publishing Company.

Secondary materials

- Anderson, R. G. W. and Christopher Lawrence. Science, Medicine and Dissent: Joseph Priestley (1733–1804). London: Wellcome Trust, 1987. ISBN 0-901805-28-9.

- Bowers, J. D. Joseph Priestley and English Unitarianism in America. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2007. ISBN 0-271-02951-X.

- Braithwaite, Helen. Romanticism, Publishing and Dissent: Joseph Johnson and the Cause of Liberty. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003. ISBN 0-333-98394-7.

- Conant, J. B., ed. “The Overthrow of the Phlogiston Theory: The Chemical Revolution of 1775–1789”. Harvard Case Histories in Experimental Science. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1950.

- Crook, R. E. A Bibliography of Joseph Priestley. London: Library Association, 1966.

- Crossland, Maurice. “The Image of Science as a Threat: Burke versus Priestley and the ‘Philosophic Revolution'”. British Journal for the History of Science 20 (1987): 277–307.

- Donovan, Arthur. Antoine Lavoisier: Science, Administration and Revolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996. ISBN 0-521-56218-X

- Eshet, Dan. “Rereading Priestley”. History of Science 39.2 (2001): 127–59.

- Fitzpatrick, Martin. “Joseph Priestley and the Cause of Universal Toleration”. The Price-Priestley Newsletter 1 (1977): 3–30.

- Garrett, Clarke. “Joseph Priestley, the Millennium, and the French Revolution”. Journal of the History of Ideas 34.1 (1973): 51–66.

- Fruton, Joseph S. Methods and Styles in the Development of Chemistry. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 2002. ISBN 0-87169-245-7.

- Gray, Henry Colin; Harrison, Brian Howard (2004). Joseph Priestly. Vol. XLV. Oxford; New York : Oxford University Press: Oxford dictionary of national biography. pp. 351–359–.

- Kramnick, Isaac. “Eighteenth-Century Science and Radical Social Theory: The Case of Joseph Priestley’s Scientific Liberalism”. Journal of British Studies 25 (1986): 1–30.

- Kuhn, Thomas. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. 3rd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996. ISBN 0-226-45808-3.

- Haakonssen, Knud, ed. Enlightenment and Religion: Rational Dissent in Eighteenth-Century Britain. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996. ISBN 0-521-56060-8.

- McCann, H. Chemistry Transformed: The Paradigmatic Shift from Phlogiston to Oxygen. Norwood: Alex Publishing, 1978. ISBN 0-89391-004-X.

- McEvoy, John G. “Joseph Priestley, ‘Aerial Philosopher’: Metaphysics and Methodology in Priestley’s Chemical Thought, from 1762 to 1781”. Ambix 25 (1978): 1–55, 93–116, 153–75; 26 (1979): 16–30.

- McEvoy, John G. “Enlightenment and Dissent in Science: Joseph Priestley and the Limits of Theoretical Reasoning”. Enlightenment and Dissent 2 (1983): 47–68.

- McEvoy, John G. “Priestley Responds to Lavoisier’s Nomenclature: Language, Liberty, and Chemistry in the English Enlightenment”. Lavoisier in European Context: Negotiating a New Language for Chemistry. Eds. Bernadette Bensaude-Vincent and Ferdinando Abbri. Canton, MA: Science History Publications, 1995. ISBN 0-88135-189-X.

- McEvoy, John G. and J.E. McGuire. “God and Nature: Priestley’s Way of Rational Dissent”. Historical Studies in the Physical Sciences 6 (1975): 325–404.

- McLachlan, John. Joseph Priestley Man of Science 1733–1804: An Iconography of a Great Yorkshireman. Braunton and Devon: Merlin Books, 1983. ISBN 0-86303-052-1.

- McLachlan, John. “Joseph Priestley and the Study of History”. Transactions of the Unitarian Historical Society 19 (1987–90): 252–63.

- Philip, Mark. “Rational Religion and Political Radicalism”. Enlightenment and Dissent 4 (1985): 35–46.

- Rose, R. B. “The Priestley Riots of 1791”. Past and Present 18 (1960): 68–88.

- Rosenberg, Daniel. Joseph Priestley and the Graphic Invention of Modern Time. Studies in Eighteenth Century Culture 36(1) (2007): pp. 55–103.

- Rutherford, Donald. Leibniz and the Rational Order of Nature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995. ISBN 0-521-46155-3.

- Schaffer, Simon. “Priestley Questions: An Historiographic Survey”. History of Science 22.2 (1984): 151–83.

- Sheps, Arthur. “Joseph Priestley’s Time Charts: The Use and Teaching of History by Rational Dissent in late Eighteenth-Century England”. Lumen 18 (1999): 135–54.

- Watts, R. “Joseph Priestley and Education”. Enlightenment and Dissent 2 (1983): 83–100.

Primary materials

- Lindsay, Jack, ed. Autobiography of Joseph Priestley. Teaneck: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1970. ISBN 0-8386-7831-9.

- Miller, Peter N., ed. Priestley: Political Writings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993. ISBN 0-521-42561-1.