In the religion of ancient Rome, a haruspex (plural haruspices; also called aruspex) was a person trained to practise a form of divination called haruspicy (haruspicina), the inspection of the entrails (exta—hence also extispicy (extispicium)) of sacrificed animals, especially the livers of sacrificed sheep and poultry. The reading of omens specifically from the liver is also known by the Greek term hepatoscopy (also hepatomancy).

The Roman concept is directly derived from Etruscan religion, as one of the three branches of the disciplina Etrusca. Such methods continued to be used well into the Middle Ages, especially among Christian apostates and pagans.

The Latin terms haruspex and haruspicina are from an archaic word, hīra = “entrails, intestines” (cognate with hernia = “protruding viscera” and hira = “empty gut”; PIE *ǵʰer-) and from the root spec- = “to watch, observe”. The Greek ἡπατοσκοπία hēpatoskōpia is from hēpar = “liver” and skop- = “to examine”.

Ancient Near East

Further information: Bārûtu and Orientalizing period

The spread of hepatoscopy is one of the clearest examples of cultural contact in the orientalizing period. It must have been a case of East-West understanding on a relatively high, technical level. The mobility of migrant charismatics is the natural prerequisite for this diffusion, the international role of sought-after specialists, who were, as far as their art was concerned, nevertheless bound to their father-teachers. We cannot expect to find many archaeologically identifiable traces of such people, other than some exceptional instances.

— Walter Burkert, 1992. The Orientalizing Revolution: Near Eastern Influence on Greek Culture in the Early Archaic Age (Thames and Hudson), p. 51.

The Babylonians were famous for hepatoscopy. This practice is mentioned in the Book of Ezekiel 21:21:

For the king of Babylon standeth at the parting of the way, at the head of the two ways, to use divination; he shaketh the arrows to and fro, he inquireth of the teraphim, he looketh in the liver.

“Ezekiel 21”. Hebrew Bible in English. Mechon-Mamre. See also: Darshan, Guy, “The Meaning of bārēʾ (Ez 21,24) and the Prophecy Concerning Nebuchadnezzar at the Crossroads (Ez 21,23-29)”, ZAW 128 (2016), 83-95. A more modern translation, from the New English Bible, translates the verse as follows: “For the king of Babylon stood at the parting of the way, at the head of the two ways, to use divination: he made his arrows bright, he consulted with images, he looked in the liver.” New English Bible online

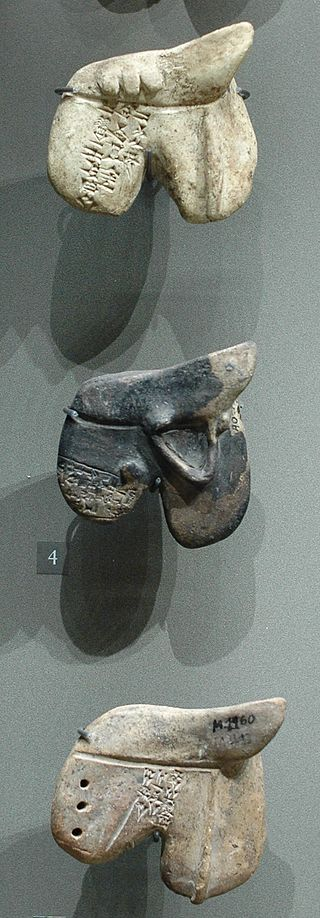

One Babylonian clay model of a sheep’s liver, dated between 1900 and 1600 BC, is conserved in the British Museum.

The Assyro-Babylonian tradition was also adopted in Hittite religion. At least thirty-six liver-models have been excavated at Hattusa. Of these, the majority are inscribed in Akkadian, but a few examples also have inscriptions in the native Hittite language, indicating the adoption of haruspicy as part of the native, vernacular cult.

- Four specimens are known to Güterbock (1987): CTH 547 II, KBo 9 67, KBo 25, KUB 4 72 (VAT 8320 in Vorderasiatisches Museum Berlin), for which see also George Sarton, Ancient Science Through the Golden Age of Greece (1952, 1970), p. 93, citing Alfred Boissier, Mantique babylonienne et mantique hittite (1935).

There is an interesting collection in the Museum of small bronzes of human figures, relative in most cases to the sphere of worship in the Etruscan and Italic environment. This statue portrays a haruspex, that is an Etruscan priest who interpreted the will of the gods by examining the liver of the animals sacrificed [cf. mirror with Calchas]. The clothing is characterized by the high headdress of skin or felt tied under the chin, because it was a bad omen if the hat of the priest fell during the ceremonies. From the right bank of the Tiber Fourth century B.C. Full cast bronze, height 17.7 cm Cat. 12040 Vatican Museums Online, Gregorian Etruscan Museum, Room III

A particularly representative class of Etruscan craft is that formed by bronze mirrors, decorated with engravings or, more rarely, in relief on the surface opposite to the reflecting part. Chronologically they are distributed between the sixth and third century B.C., with a particular development in the 4th cent. BC. This famous mirror shows an elderly haruspex intent on examining the liver of a sacrificed animal for drawing auspices from it. The Etruscan inscription describes him as Kalkhas, that is the mythical Greek soothsayer Calchas represented here in the Etruscan iconographic version with the attribute of wings, a clear characteristic that underlines his function of go-between between earthly and transcendent reality. The foot placed on a rock is to be noted. This is a fundamental action in the divining process by the haruspex who in doing this establishes contact with the earth as the site of the natural sphere and of the underworld. Vulci Late fifth century B.C. Cast bronze, height 18.5 cm; diam. 14.8 cm Cat. 12240 Vatican Museums Online, Gregorian Etruscan Museum, Room III. [This mirror is mentioned elsewhere including in a post.titled Adam Napat (and Nethuns)]

Haruspicy in Ancient Italy

Roman haruspicy was a form of communication with the gods. Rather than strictly predicting future events, this form of Roman divination allowed humans to discern the attitudes of the gods and react in a way that would maintain harmony between the human and divine worlds (pax deorum). Before taking important actions, especially in battle, Romans conducted animal sacrifices to discover the will of the gods according to the information gathered through reading the animals’ entrails. The entrails (most importantly the liver, but also the lungs and heart) contained a large number of signs that indicated the gods’ approval or disapproval. These signs could be interpreted according to the appearance of the organs, for example, if the liver was “smooth, shiny and full” or “rough and shrunken”. The Etruscans looked for the caput iocineris, or “head of the liver”. It was considered a bad omen if this part was missing from the animal’s liver. The haruspex would then study the flat visceral side of the liver after examining the caput iocineris.

- Driediger-Murphy, Lindsay G, and Eidinow, Esther. Ancient Divination and Experience. Oxford: Oxford University Press USA – OSO, 2019.

- Johnston, Sarah Iles. “Divination: Greek and Roman Divination”. In Encyclopedia of Religion, 2nd ed., edited by Lindsay Jones, 2375–2378. Vol. 4. Detroit, Michigan: Macmillan Reference USA, 2005. Gale eBooks.

- Stevens, Natalie L. C. “A New Reconstruction of the Etruscan Heaven.” American Journal of Archaeology, vol. 113, no. 2, Archaeological Institute of America, 2009

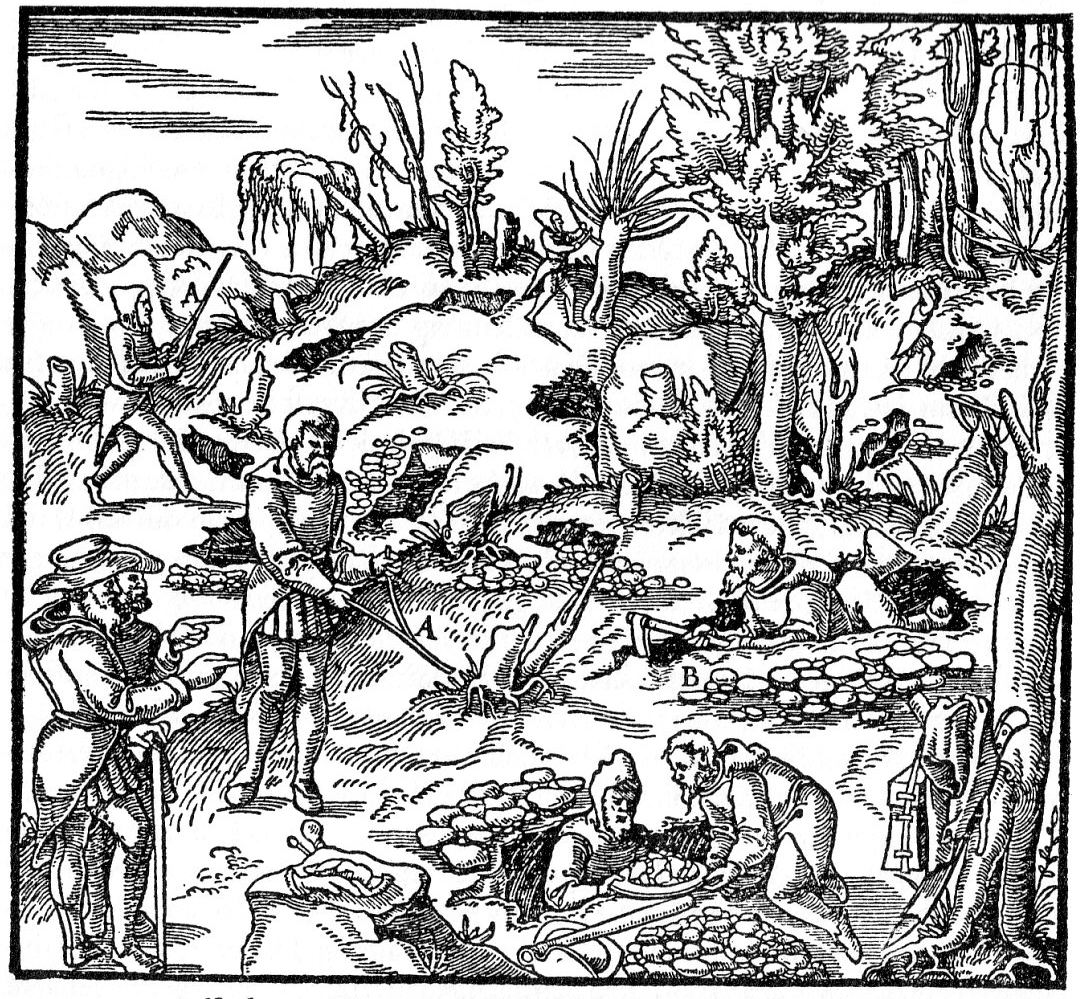

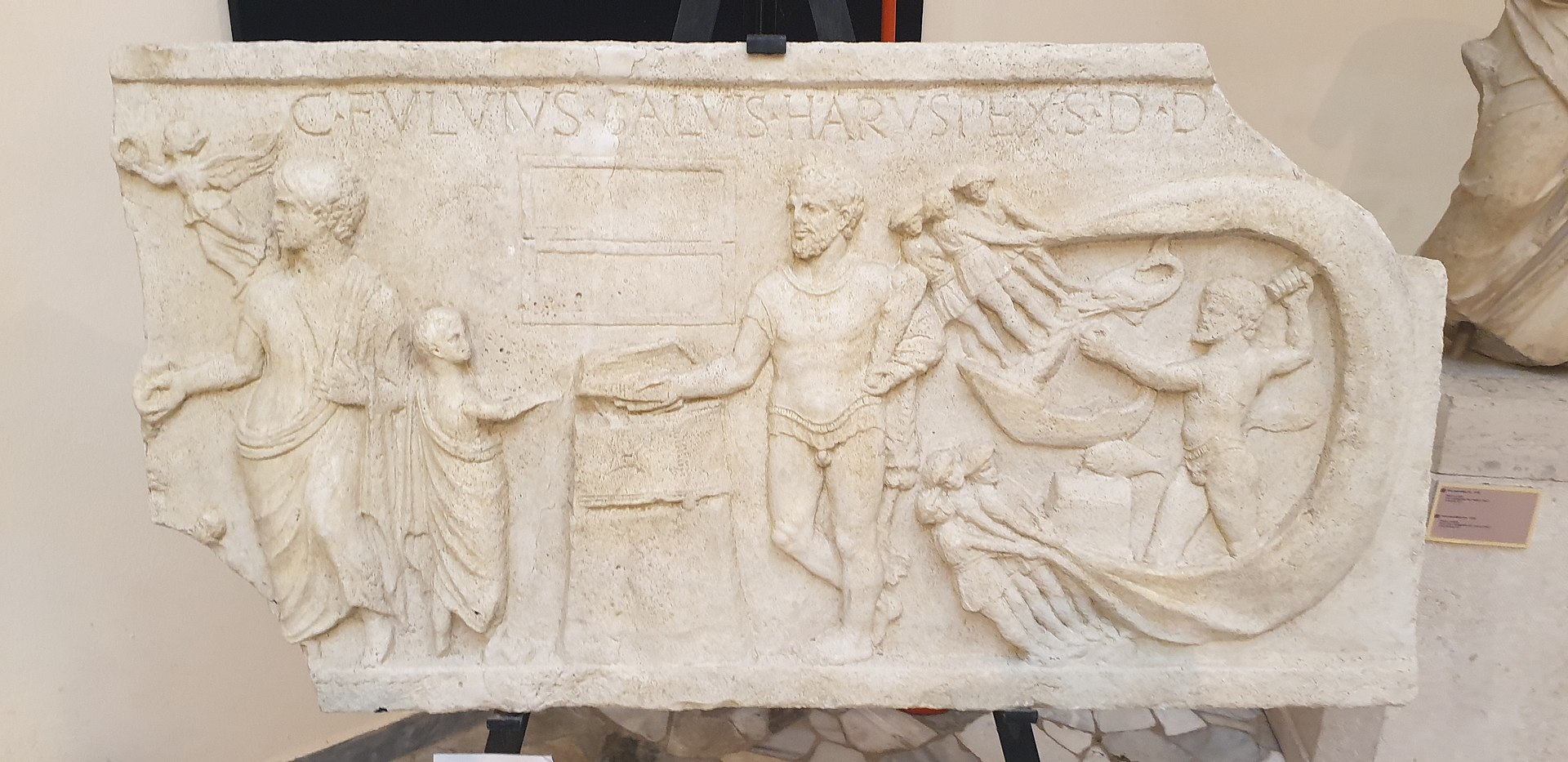

Haruspicy in Ancient Italy originated with the Etruscans. Textual evidence for Etruscan divination comes from an Etruscan inscription: the priest Laris Pulenas’ (250–200 BCE) epitaph mentions a book he wrote on haruspicy. A collection of sacred texts called the Etrusca disciplina, written in Etruscan, were essentially guides on different forms of divination, including haruspicy and augury. In addition, a number of archeological artifacts depict Etruscan haruspicy. These include a bronze mirror with an image of a haruspex dressed in Etruscan priest’s clothing, holding a liver while a crowd gathers near him. Another significant artifact relating to haruspicy in Ancient Italy is the Piacenza Liver. This bronze model of a sheep’s liver was found by chance by a farmer in 1877. Names of gods are etched into the surface and organized into different sections. Artifacts depicting haruspicy exist from the ancient Roman world as well, such as stone relief carvings located in Trajan’s Forum.

- Driediger-Murphy, Lindsay G, and Eidinow, Esther. Ancient Divination and Experience. Oxford: Oxford University Press USA – OSO, 2019.

- MacIntosh Turfa, Jean, and Tambe, Ashwini, eds. The Etruscan World. London: Taylor & Francis Group, 2013. ProQuest Ebook Central.

See also

Bibliography

- Walter Burkert, 1992. The Orientalizing Revolution: Near Eastern Influence on Greek Culture in the Early Archaic Age (Thames and Hudson), pp 46–51.

- Derek Collins, “Mapping the Entrails: The Practice of Greek Hepatoscopy” American Journal of Philology 129 [2008]: 319-345

- Marie-Laurence Haack, Les haruspices dans le monde romain (Bordeaux : Ausonius, 2003).

- Hans Gustav Güterbock, ‘Hittite liver models’ in: Language, Literature and History (FS Reiner) (1987), 147–153, reprinted in Hoffner (ed.) Selected Writings, Assyriological Studies no. 26 (1997).[1]

External links

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). “Haruspices” . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 13 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 37–38. This source suggests that Greek and Roman haruspices used the entrails of human corpses; the victim should be “without spot or blemish”.

- Haruspices, article in Smith’s Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities

- Figurine of Haruspex, 4th Cent. B.C. Vatican Museums Online, Gregorian Etruscan Museum, Room III

- l. Starr (1992). “Chapters 1 and 2 of the bārûtu”. State Archives of Assyria Bulletin. 6: 45–53.

| Etruscan-related topics |

|---|