0

0

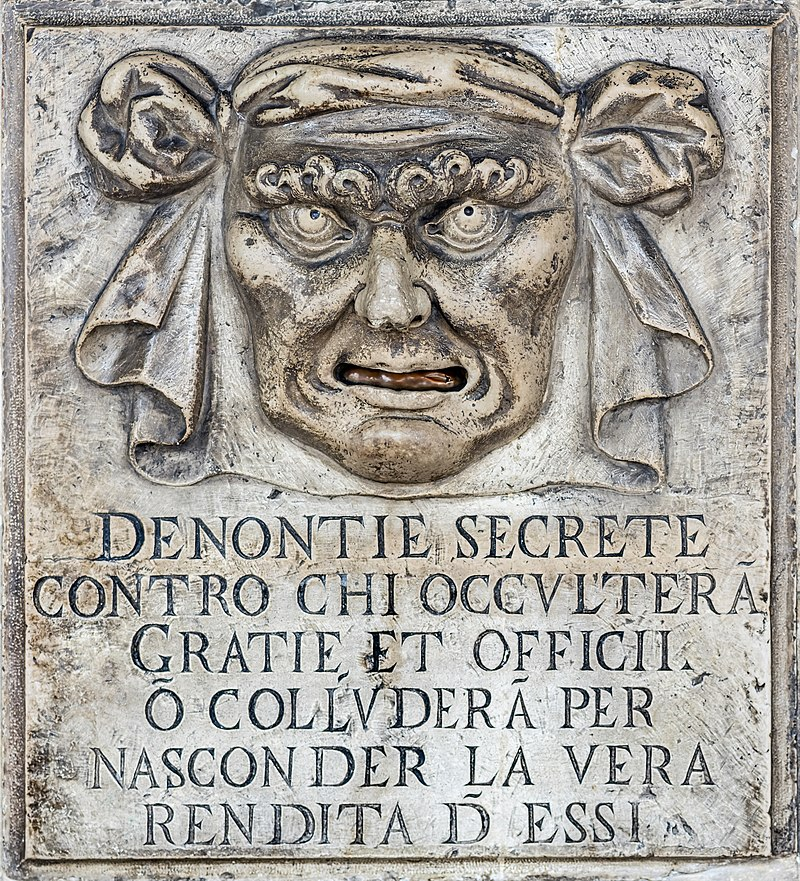

Mouth of the Lion

Denunciation (from Latin denuntiare, “to denounce”) is the act of publicly assigning to a person the blame for a perceived wrongdoing with the hope of bringing attention to it. Notably, centralized social control in authoritarian states requires some level of cooperation from the populace.

- “denounce”. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved July 20, 2018.

Denunciation boxes, or bocche di leone (lions’ mouths), were scattered throughout Venice, from the Doge’s Palace to the Dorsoduro district. Each stone receptacle resembled an intricately carved face, often that of a lion—the winged lion of St. Mark is the symbol of Venice. Alternative designs were of a “bad face” expression. In place of the mouth there was a hole or slot, to insert paper documents with the secret complaints. Behind these plaques inside the building, there was a small wooden box to securely collect all the complaints. The keys to these boxes were kept by the Magistrates and only the heads of each district (sestieri) could open them.

- Dietz, Kasia, Need to complain? Here’s how Renaissance-era Venetians did it “Trade disputes. Tax gripes. All manner of ancient accusations were dropped into the ‘bocche di leone,’ or lions’ mouths”. December 31, 2020, National Geographic website

- Ian Coulling FRPS, Mouths of the Lion “Mouths of the Lion, refers to the famous “Bocche dei Leone”, that the Venetian Republic used as a means of collecting complaints or denunciations; against other citizens, or the authorities. Essentially, they were an early form of “Post-box”, embedded into the wall of churches or certain state buildings; giving Venetian’s the means by which they could secretly and securely denounce another, if they were suspected of breaking the law.” Images of Venice website

The most dangerous secret denunciations were those who were presented with charges of treason and conspiracy against the State; in which case the sentence was the death penalty, exile, or relegation. In 1387, the Council of Ten ordered that anonymous allegations sent without signature of the accuser and without reliable witnesses for the prosecution on the circumstances reported were to be burned without taking account of. The Elders of the Ten (I Savi dei Dieci) and the Directors of the Ten (Consiglieri dei Dieci) accepted anonymous complaints if State safety was at stake and with the approval of a large majority of their votes. In 1542, it was decreed that acceptance of complaints were quoted only if at least three witnesses were present at the event.

- Ian Coulling FRPS, Mouths of the Lion “Mouths of the Lion, refers to the famous “Bocche dei Leone”, that the Venetian Republic used as a means of collecting complaints or denunciations; against other citizens, or the authorities. Essentially, they were an early form of “Post-box”, embedded into the wall of churches or certain state buildings; giving Venetian’s the means by which they could secretly and securely denounce another, if they were suspected of breaking the law.” Images of Venice website

There was a financial incentive for citizens to snitch on one another as those making a denunciation were rewarded for their efforts if their information proved correct. Accusers knew that they would be given the punishment of the crimes if they reported falsely.

- Lown, David, Venice: The Lion’s Mouth, Walks In Rome website Est. 2001

- Ian Coulling FRPS, Mouths of the Lion “Mouths of the Lion, refers to the famous “Bocche dei Leone”, that the Venetian Republic used as a means of collecting complaints or denunciations; against other citizens, or the authorities. Essentially, they were an early form of “Post-box”, embedded into the wall of churches or certain state buildings; giving Venetian’s the means by which they could secretly and securely denounce another, if they were suspected of breaking the law.” Images of Venice website

The procedure had such an evil reputation that when someone joked to Montesquieu that he was being watched by the Ten, he immediately packed his bags and left town.

- Dana Facaros & Michael Pauls, Bocche dei Leoni – ‘Mouths of Truth’ Venice Art & Culture app

Throughout the 17th century, Venice was known for having an effective, though strict, legal system—in part because of the boxes, also called bocche che parlano (mouths that speak). Each state department had its own box. And across the city, different boxes addressed different issues—such as taxes, market fraud, or trade disputes—depending on their location. This spoke to the system of government in place at the time, an oligarchic republic led by the doge and known locally as La Serenissima (Most Serene Republic of Venice). The box embedded in the wall of the church of Santa Maria della Visitazione in Dorsoduro, for example, was used to complain about garbage in the canals. It read “denunciations related to public health for the Sestiere of Dorsoduro.” Centuries later, this box remains, and so too does the pollution problem.

- Dietz, Kasia, Need to complain? Here’s how Renaissance-era Venetians did it “Trade disputes. Tax gripes. All manner of ancient accusations were dropped into the ‘bocche di leone,’ or lions’ mouths”. December 31, 2020, National Geographic website

It was a legal system known as inquisitorial. Inquiry would be started from a public accusation which often involved witnesses, or a secret denunciation. Venice wasn’t the only place that followed this kind of protocol. During the medieval and Renaissance periods, “many cities and countries had systems for anonymous denunciation of one kind or another—that’s part of how the legal system worked throughout Europe.

Filippo de Vivo, historian and author of Information and Communication in Venice: Rethinking Early Modern Politics.

Wikipedia says this is still the case for much of the world all of the time and for all of the world much of the time: An inquisitorial system is a legal system in which the court, or a part of the court, is actively involved in investigating the facts of the case.

After the fall of the Republic, Napoleon ordered the denunciation boxes taken down or destroyed, to prove that French law now prevailed but fortunately a few of these curiosities can still be seen today, around the city. Seek them out on the Palazzo Ducale (there are two), in the Torcello museum, San Martino, Santa Maria della Visitazione, and the gate of the Law School of the University of Venice (although this last one may be a copy).

- Ian Coulling FRPS, Mouths of the Lion “Mouths of the Lion, refers to the famous “Bocche dei Leone”, that the Venetian Republic used as a means of collecting complaints or denunciations; against other citizens, or the authorities. Essentially, they were an early form of “Post-box”, embedded into the wall of churches or certain state buildings; giving Venetian’s the means by which they could secretly and securely denounce another, if they were suspected of breaking the law.” Images of Venice website

- Dana Facaros & Michael Pauls, Bocche dei Leoni – ‘Mouths of Truth’ Venice Art & Culture app

“These were the terrible Lions’ Mouths. … these were the throats down which went the anonymous accusation thrust in secretly in the dead of night by an enemy, that doomed many an innocent man to walk the Bridge of Sighs and descend into the dungeon which none entered and hoped to see the sun again”.

Mark Twain, Innocents Abroad

There is a connection to snapdragons.

The first act of Amilcare Ponchielli ‘s opera La Gioconda is titled The Lion’s Mouth because one of the characters, Barnaba, during the monologue “O monument!”, inserts a denunciation into a lion’s mouth accusing the two lovers Enzo and Laura.

Lions’ Mouths are mentioned repeatedly in the bible. Daniel in the Lions’ Den, 2 Timothy 4:17, Hebrews 11:33, Psalm 22:21, Psalm 58:6, Revelation 13:2 etc.

Dunciation

The following two forms of cooperation occur: first, authorities actively use incentives to elicit denunciations from the populace, either through coercion or through the promise of rewards. Second, authorities passively gain access to political negative networks, as individuals denounce to harm others whom they dislike and to gain relative to them. Paradoxically, social control is most effective when authorities provide individuals maximum freedom to direct its coercive power.

- Bergemann, Patrick (2017). “Denunciation and Social Control”. American Sociological Review. 82 (2): 384–406. doi:10.1177/0003122417694456. S2CID 151547072.

Commonly, denunciation is justified by proponents because it allegedly leads to a better society by reducing or discouraging crime. The punishment of the denounced person is said to be justified because the convicted criminal is morally deserving of punishment. Yet, this reasoning does not present a compelling argument for society’s right to inflict punishment on a specific individual. Society may recognize a crime’s impact on law-abiding society, but traditional punishment theories do not even attempt to deal with punishment’s effect on law-abiding society. Just as punishment may impact potential lawbreakers, it may also impact those who abide by the law. To fully understand society’s right to inflict punishment, one must recognize punishment’s full impact on all segments of society, not just on potential lawbreakers.

- Rychlak, Ronald J. (1990): Society’s moral right to punish: A further exploration of the denunciation theory of punishment. Tulane Law Review, vol. 65, No. 2, 1990, online since 5 Jun 2013 – ” To fully understand society’s right to inflict punishment, one must recognize punishment’s full impact on all segments of society, not just the potential lawbreakers.”

Athenian democracy used the process of ostracism to allow popular anonymous denunciations. The term “ostracism” is derived from the pottery shards that were used as voting tokens, called ostraka in Greek. Broken pottery, abundant and virtually free, served as a kind of scrap paper (in contrast to papyrus, which was imported from Egypt as a high-quality writing surface, and too costly to be disposable).

- Burckhardt, Leonhard; Burckhardt, Leonhard Alexander; Ungern-Sternberg, Jürgen von (2000). Grosse Prozesse im antiken Athen (in German). C.H. Beck. pp. 68–77. ISBN 3-406-46613-3.

- “The Price of Papyrus in Greek Antiquity, Gustave Glotz 1929”. www.marxists.org. Retrieved 21 March 2023.

- Skeat, T.C. (1995). “Was papyrus regarded as « cheap » or « expensive » in the ancient world?”. Aegyptus. 75 (1/2): 75–93. ISSN 0001-9046.

Other cities are known to have set up forms of ostracism on the Athenian model, namely Megara, Miletos, Argos and Syracuse, Sicily. In the last of these it was referred to as petalismos, because the names were written on olive leaves. Petalism was first and exclusively recorded in Diodorus Siculus’ Bibliotheca historica. By 450 BCE, the practice had largely been abandoned by the Syracusan assembly before eventually being abolished altogether.

- “Perseus Under Philologic: Diod. Sic. 11.87”. artflsrv02.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 2020-11-04.

- Rhodes, Peter J. “Petalismos.” In Brill’s New Pauly. 4th ed. vol. 10. 15 vols. Boston, MA: Brill, 2002.

See also

- Denunciation (penology)

- Delator

- Stop Snitchin’

- Witch hunt

- Yiku sitian

- Ostracism

- McCarthyism

- Petalism

- Social control

- Sycophancy

- This list is almost endless and many of the related subjects have generated a lot more information than the original subject here which is the boxes

Further reading (denunciation)

- Bergemann, Patrick (2017), Denunciation and Social Control, American Sociological Review, vol. 82, issue 2, 2017, first online, February 1, 2017

- Kubátová, Hana (2018). “Accusing and Demanding: Denunciations in Wartime Slovakia”. In Skitolsky, Lissa; Glowacka, Dorota (eds.). New Approaches to an Integrated History of the Holocaust: Social History, Representation, Theory. Lessons and Legacies. Vol. XIII. Northwestern University Press. pp. 92–111. ISBN 978-0-8101-3768-4.

- Lucas, Colin (2017): The Theory and Practice of Denunciation in the French Revolution. The Journal of Modern History, vol. 68 (4), pp. 768-785, first online, December 4, 1996