Lili Elbe, Danish painter and trans woman who was castrated by one nazi (1930) and dead a short time later after a womb transplant performed by another nazi (1931)

Lili Ilse Elvenes (1882 – 1931), better known as Lili Elbe, was a Danish painter, trans woman and among the early recipients of gender-affirming surgery (sex reassignment surgery).

They say that about all of them…that they were the first or one of the first or some kind of pioneer. I suspect the truth is closer to ‘they have been castrating everything that moves since the beginning of time.’

- Hirschfeld, Magnus. Chirurgische Eingriffe bei Anomalien des Sexuallebens: Therapie der Gegenwart, pp. 67, 451–455

- Koymasky, Matt & Andrej (17 May 2003). “Famous GLTB: Lili Elbe”. HistoryVSHollywood.com. Archived from the original on 10 October 2007. Retrieved 2 February 2016. Based on Brown, Kay (1997); Aldrich R. & Wotherspoon G., Who’s Who in Gay and Lesbian History, from Antiquity to WWII, Routledge, London, 2001.[better source needed]

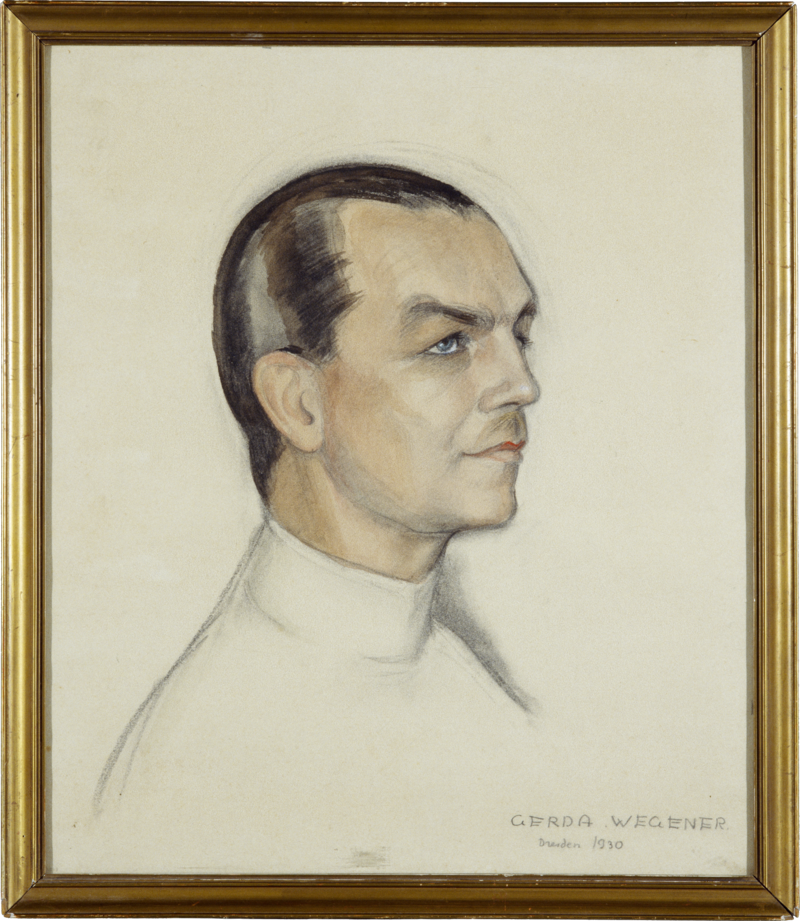

She was a painter under her birth name Einar Wegener. After transitioning in 1930, she changed her legal name to Lili Ilse Elvenes and stopped painting and later adopted the surname Elbe. She was the first known recipient of a uterus transplant in attempt to achieve pregnancy but died due to the subsequent complications.

- Meyer 2015, pp. 15, 310–313.

- Meyer 2015, pp. 311–314

- Goldberg, A.E.; Beemyn, G. (2021). The SAGE Encyclopedia of Trans Studies. SAGE Publications. p. 261. ISBN 978-1-5443-9382-7. Retrieved 12 January 2023.

- Kroløkke, C.; Petersen, T.S.; Herrmann, J.R.; Bach, A.S.; Adrian, S.W.; Klingenberg, R.; Petersen, M.N. (2019). The Cryopolitics of Reproduction on Ice: A New Scandinavian Ice Age. Emerald Studies in Reproduction, Culture and Society. Emerald Publishing Limited. p. 154. ISBN 978-1-83867-044-3. Retrieved 31 January 2023.

- “Lili Elbe Biography”. Biography.com. A&E Television Networks. Archived from the original on 6 January 2019. Retrieved 11 December 2015.

- “Lili Elbe: the transgender artist behind The Danish Girl”. This Week Magazine. 18 September 2015. Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 1 February 2016.

- “The Danish Girl (2015)”. HistoryVSHollywood.com. History vs Hollywood. Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 1 February 2016.[better source needed]

The surgeries

In 1930, Elbe went to Germany for sex reassignment surgery which was highly experimental at the time. While in Germany, Elbe stayed in the Hirschfeld Institute for Sexual Science. Prior to commencing any surgical procedures, Elbe’s psychological health was evaluated by German sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld through a series of tests. A series of four operations were then carried out over a period of two years.

The first surgery performed in Berlin was the removal of the testicles carried out by Erwin Gohrbant, a German surgeon, university teacher and decorated Nazi who also served as vice president of the Berlin regional association of the German Red Cross. Among other things, he participated in the development of human experiments, conducted on prisoners of the Dachau concentration camp, investigating the problems of mortality due to hypothermia.

Erwin Gohrbant biographical information (Wikipedia)

During the National Socialist period, Gohrbandt was a research assistant for surgical questions in the Social Office of the Reich Youth Leader. From August 1939, Gohrbandt was a consultant surgeon to the army and (from 1940?) the inspector of medical services in the Luftwaffe. With effect from October 1, 1940, he became Head of the Surgical Department at the Municipal Robert Koch Hospital and at the same time became Clinic Director of the Third Appointed Surgical University Clinic. Gohrbandt participated in the conference on medical questions in distress and winter death on October 26 and 27, 1942. From 1944 he was a member of the scientific advisory board of the General Commissioner for the Sanitation and Health Service Karl Brandt.

- Brandt joined the Nazi Party in 1932 and became Adolf Hitler‘s escort doctor in August 1934. A member of Hitler’s inner circle at the Berghof, he was selected by Philipp Bouhler, the head of Hitler’s Chancellery, to administer the Aktion T4 euthanasia program. Brandt was later appointed the Reich Commissioner of Sanitation and Health (Bevollmächtigter für das Sanitäts- und Gesundheitswesen). Accused of involvement in human experimentation and other war crimes, Brandt was indicted in late 1946 and faced trial before a U.S. military tribunal along with 22 others in United States of America v. Karl Brandt, et al. He was convicted, sentenced to death, and hanged on 2 June 1948.

In the post-war period, Gohrbandt was Ferdinand Sauerbruch‘s deputy in the office of the city council for health care in all of Berlin.

- In 1937, Ferdinand Sauerbruch became a member of the newly established Reich Research Council that supported “research projects” of the SS, including experiments on prisoners in the concentration camps. As head of the General Medicine Branch of the RRC, it was alleged that he personally approved the funds which financed August Hirt‘s experiments with mustard gas on prisoners at Natzweiler concentration camp from 1941 until 1944. However, he was one of the few university professors who publicly spoke out against the NS-Euthanasia program T4.[citation needed] In 1942, he became Surgeon General to the army. In mid-September 1943, Sauerbruch was awarded the Knight’s Cross of the War Merit Cross with Swords. On 12 October 1945, he was charged by the Allies for having contributed to the Nazi dictatorship, but acquitted for lack of evidence.

In 1950-51 Gohrbandt was chairman of the Berlin Surgical Society. He was commissioned by the Soviet military administration in Germany and the Berlin magistrate to ensure sanitation and to monitor hygiene regulations. He drove the reconstruction of the war-damaged Moabit Hospital and headed its surgical department until December 31, 1958. At the same time, he resumed his lectures at the newly founded Free University of Berlin and published the Central Journal for Surgery in 1946. Effective December 31, 1958, he retired. He ran an outpatient clinic in Berlin-Tiergarten until his death in 1965.

- Ernst Klee: Das Personenlexikon zum Dritten Reich, Frankfurt am Main 2007, S. 191f.

- Kösener Corpslisten 1930, 66/461

- Harald Rimmele: Biografie von Dorchen Richter. hirschfeld.in-berlin.de

- “A Trans Timeline”. Trans Media Watch. Archived from the original on 2018-12-26. Retrieved 2016-02-03.

- Woolf, Linda (2017), “Nazi Doctors & Other Perpetrators of Nazi Crimes”, Nazi Science: Human Experimentation vs. Human Rights, retrieved 2023-03-11

- The activities of surgeon Erwin Gohrbandt (1890-1965) on behalf of the Berlin University, the city’s municipal council and the Berlin Surgical Society. Z Arztl Fortbild (Jena). 1990;84(19):1005-8. German. PMID: 2270698.

- Walther Killy, Rudolf Vierhaus (Hrsg.): Deutsche Biographische Enzyklopädie. München 1995–1999

- Rolf Winau, Ekkehard Vaubel: Chirurgen in Berlin: 100 Porträts. Berlin 1983

- Karl Philipp Behrendt: Die Kriegschirurgie von 1939 – 1945 aus der Sicht der Beratenden Chirurgen des deutschen Heeres im Zweiten Weltkrieg. (PDF; 2,3 MB) Dissertation, Freiburg im Breisgau, 2003

- Zum Wirken des Chirurgen Erwin Gohrbandt (1890–1965) für die Berliner Universität, den Magistrat der Stadt und die Berliner Chirurgische Gesellschaft. In: Zeitschrift für ärztliche Fortbildung, 84, 1990, S. 1005–1008

- Ben-Amos, Batsheva. “Karl Brandt: The Nazi Doctor. Medicine and Power in the Third Reich (review)”. Retrieved 10 November 2014.

- Hamilton 1984, p. 138. Hamilton, Charles (1984). Leaders & Personalities of the Third Reich, Vol. 1. R. James Bender Publishing. ISBN 0-912138-27-0.

- Schmidt: Hitlers Arzt, Berlin 2009, ISBN 978-3-351-02671-4 Schmidt, Ulf. Karl Brandt: The Nazi Doctor: Medicine and Power in the Third Reich. London, Hambledon Continuum, 2007.

- Lifton, Robert Jay (1986). The Nazi Doctors: Medical Killing and the Psychology of Genocide. United States: Basic Books. p. 114. ISBN 0-465-04905-2. Retrieved 2013-03-23.

karl brandt surgeon.

- Joachimsthaler 1999, p. 296.Joachimsthaler, Anton (1999) [1995]. The Last Days of Hitler: The Legends, the Evidence, the Truth. Trans. Helmut Bögler. London: Brockhampton Press. ISBN 978-1-86019-902-8.

- Schmidt, U. (2007). Karl Brandt: The Nazi Doctor: Medicine and Power in the Third Reich. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-84725-031-5. Retrieved 2022-10-11.

- Pathways to Human Experimentation, 1933-1945: Germany, Japan, and the United States by Gerhard Baader, Susan E. Lederer, Morris Low, Florian Schmaltz and Alexander V. Schwerin, Osiris, 2nd Series, Vol. 20, Politics and Science in Wartime: Comparative International Perspectives on the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute (2005), p216

- “Ernst Ferdinand Sauerbruch”.

- Youngson RM (1997). “The demented surgeon is operating”. Medical Curiosities. New York: Carroll & Graf.

- Dubious Role Models:Study Reveals Many German Schools Still Named After Nazis Jan Friedmann 02/04/2009 Spiegel Online

Elbe’s subsequent surgeries

The remainder of her surgeries were carried out by Kurt Warnekros, a doctor at the Dresden Municipal Women’s Clinic who was a member of the NSDAP by 1933 (from 1921 onwards, the NSDAP party chairman was the later Reich Chancellor Adolf Hitler, under whom they ruled the so-called Third Reich from 1933 to 1945. After the end of the Second World War in 1945, it was classified as a criminal organization with all its subdivisions by the Allied Control Council Law No. 2 and was thus banned and dissolved.)

Kurt Warnekros biographical information

The English Wikpedia page says:

Kurt Warnekros (November 15, 1882–September 30, 1949) was a German gynaecologist and pioneer in sexual reassignment surgery. Kurt Warnekros was born on November 15, 1882 in the family of the professor of medicine Ludwig Warnekros at the University of Berlin. Warnekros himself studied medicine in Würzburg and Berlin from 1902 to 1907. He received his medical license in 1908 and worked at the Women’s Hospital of the University of Berlin from 1909. In 1918 Warnekros was appointed professor and in 1924 as head of the hospital. In addition to working as a gynecologist, Warnekros also worked scientifically in the field of X-rays, making x-rays of babies in the womb. In 1930, following a trip to Paris, Warnekros took Lili Elbe (née Wegener) as a patient. As a result, Warnekros arranged a series of operations serving as Elbe’s feminizing genitoplasty. This was following the operation performed at Magnus Hirschfeld‘s Institute for Sexual Research for the removal of Elbe’s testicles. A series of three operations was performed. Lili died after the last (as well as most ambitious) operation ventured, when her body rejected the transplanted womb.

- “First gender reassignment in history”. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- “Trans Media Watch”. www.transmediawatch.org. Archived from the original on 2013-05-07.

- Harrod, Horatia (25 April 2016). “The tragic true story behind the Danish Girl”. The Telegraph.

- “Lili Elbe Digital Archive”. lilielbe.org. Retrieved 2019-04-01.

- “The Danish Girl (2015)”. IMDb.

The German Wikipedia page roughly translates as:

As the son of the later professor of medicine Ludwig Warnekros at the University of Berlin , Warnekros studied medicine in Würzburg and Berlin from 1902 to 1907. In 1908 he received his license to practice medicine. From 1909 he worked at the women’s clinic of the University of Berlin, where he also habilitated in 1914. In 1918 Warnekros was appointed professor and in 1924 he took over the provisional management of the clinic. In addition to his work as a gynecologist and obstetrician, Warnekros also worked scientifically in the field of X-ray radiation together with his sister, a trained X-ray assistant. He published a well-regarded book with X-rays of babies in the womb. In 1925 he took over the management of the women’s clinic of the city hospital Dresden-Johannstadt. As a successful obstetrician, he soon had a large number of prominent patients including Princess Ileana of Romania, a daughter of King Ferdinand I of Romania , and the wife of Soviet Foreign Minister Maxim Litvinov. In 1930, Warnekros made headlines when he performed one of the first sex reassignment surgeries. Patient Lili Elbe was previously known as a landscape and architectural painter under the name Einar Wegener who was born with both male and female organs. After ovarian transplantation, uterine transplantation was performed in a fourth operation. A few months later in 1931 complications arose, probably due to transplant rejection, from which Lili Elbe died. It was only more than 80 years later that this operation was successfully performed for the first time worldwide. In 1933 Warnekros became a member of the NSDAP . Nevertheless, in 1936 investigations were launched against him as a “Jewish favourite” – before 1933 he had also treated Marie-Anne von Goldschmidt-Rothschild, daughter of the German industrialist Fritz von Friedlaender-Fuld and a member of the well-known Rothschild family, and he also continued to take Jewish patients. (Since he also treated the wife of the Saxon NSDAP Gauleiter Martin Mutschmann?) the investigations were soon discontinued. He continued to treat Jewish patients until 1944….Forced sterilizations were also carried out under Warnekros at the women’s clinic in Johannstadt. In 1944, Warnekros helped Eva Olbricht, the wife of Friedrich Olbricht, one of the co-conspirators in the July 20, 1944 assassination, on her escape from Nazi kinship imprisonment. The air raids on Dresden on February 13 and 14, 1945 also destroyed the women’s clinic, and many of Warnekros’ patients lost their lives. Warnekros arranged for the survivors to be transported to Kreischa, where the women’s clinic was evacuated. Warnekros remained in charge of the women’s clinic until 1948, but ultimately stopped operating himself due to illness. Shortly before his death he moved to Paris at the invitation of the Baroness von Goldschmidt-Rothschild. Warnekros was initially buried in the Cimetière du Père-Lachaise in 1949. In 1954 his urn was transferred to the family grave at the Grunewald Cemetery in the Halensee district of Berlin.

- A Man Changes His Sex: A Life Confession , edited from Papers Left Behind by Niels Hoyer . Translated from the Danish original Fra Mand til Kvinde by Ernst Harthern-Jacobson. Reissner, Dresden 1932, p. 15.

- Sabine Meyer, “How Lili became a real girl”, Transcript Verlag, 2015, pages 271-281

- Lili Elbe Biography. In: Biography.com. A&E Television Networks, accessed December 11, 2015 .

- Horatia Harrod: The tragic true story behind The Danish Girl . In: The Telegraph , 8 December 2015. Retrieved 11 December 2015.

- http://www.biography.com/people/lili-elbe-090815

- Criticism of this version see: Susanne Kailitz: The Experiment. In: The Time . January 12, 2012, accessed July 26, 2012.

- The world’s first womb transplant: Landmark surgery brings hope to millions of childless women – and it could be in Britain soon. May 25, 2012 .

- Albrecht Scholz, Birgit Töpolt: The practice of forced sterilization in Dresden. ( Memento des Originals from January 10, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. In: Medical Journal Saxony. Vol. 16 (2005), no. 4, pp. 164–167 (PDF file, 139 kB). Retrieved January 10, 2016.

- Klaus Knerger: The Grave of Kurt Warnekros. In: knerger.de. Retrieved 20 June 2022 .

- The Danish Girl (2015) – Full Cast & Crew , IMDb , accessed 8 January 2016.

Elbe’s second and third surgeries

The second operation was to implant an ovary onto her abdominal musculature, the third to remove the penis and the scrotum.

Elbe’s fourth surgery

In 1931, Elbe returned for her fourth surgery, to transplant a uterus and construct a vaginal canal. This made her one of the earliest transgender women to undergo a vaginoplasty surgery, a few weeks after Erwin Gohrbandt performed the experimental procedure on Dora Richter.

- “Lili Elbe Biography”. Biography.com. A&E Television Networks. Archived from the original on 6 January 2019. Retrieved 11 December 2015.

- “Lili Elbe: the transgender artist behind The Danish Girl“. This Week Magazine. 18 September 2015. Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 1 February 2016.

- “The Danish Girl (2015)”. HistoryVSHollywood.com. History vs Hollywood. Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 1 February 2016.[better source needed]

- “A Trans Timeline – Trans Media Watch”. Trans Media Watch. Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- Harrod, Horatia (8 December 2015). “The tragic true story behind The Danish Girl”. The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 21 April 2016. Retrieved 11 December 2015.

Death

Following Elbe’s fourth surgery, her immune system rejected the transplanted uterus. This ultimately caused an infection, which led to her death from cardiac arrest on 13 September 1931 in Dresden, Germany, three months after the surgery.

- “Lili Elbe Biography”. Biography.com. A&E Television Networks. Archived from the original on 6 January 2019. Retrieved 11 December 2015.

- “Lili Elbe: the transgender artist behind The Danish Girl“. This Week Magazine. 18 September 2015. Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 1 February 2016.

- “The Danish Girl (2015)”. HistoryVSHollywood.com. History vs Hollywood. Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 1 February 2016.[better source needed]

- Harrod, Horatia (8 December 2015). “The tragic true story behind The Danish Girl”. The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 21 April 2016. Retrieved 11 December 2015.

- “Lili Elbe (Einar Wegener) 1882–1931”. Danmarkshistorien.dk (in Danish). Danmarkshistorien.dk. 10 September 2013. Archived from the original on 5 April 2016. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- “Trans Media Watch”. Trans Media Watch. Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

All of Lili Elbe’s medical documents were ruined as a consequence of the Allied bombing raids that destroyed the clinic and archives. They say that all the time too. Sometimes they say that right alongside photographic evidence to the contrary. With or without medical records, I’m having some difficulty understanding why this is so celebrated. She died. They all died.

It is speculated that Elbe was intersex, although that has been disputed. Some reports and another page indicate that she already had rudimentary ovaries in her abdomen and/or both male and female organs and may have had Klinefelter syndrome. Klinefelter syndrome (KS), also known as 47,XXY, is an aneuploid genetic condition where a male has an additional copy of the X chromosome. The primary features are infertility and small, poorly functioning testicles. Usually, symptoms are subtle and subjects do not realize they are affected. In August 2022, a team of scientists published a study of a skeleton found at Torre Velha, Municipality of Bragança in north-eastern Portugal. The male was buried in a cut grave around 1,000CE, and found from DNA tests to be the earliest known person with this syndrome. Dear lord.

- Hoyer, Niels, ed. (2004). Man into woman: the first sex change, a portrait of Lili Elbe: the true and remarkable transformation of the painter Einar Wegener. London: Blue Boat Books. pp. vii, 26–27, 172. ISBN 978-0-9547072-0-0.

- “Lili Elbe’s autobiography, Man into Woman”. OII Australia – Intersex Australia. OII Australia. 16 April 2009. Archived from the original on 28 March 2015. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- Vacco, Patrick (29 April 2014). “Les Miserables Actor Eddie Redmayne to Star as Queer Artist Lili Elbe”. The Advocate. Archived from the original on 29 September 2015. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- Kaufmann, Jodi (January 2007). “Transfiguration: a narrative analysis of male‐to‐female transsexual”. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education. 20 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1080/09518390600923768. S2CID 144939698.

- Koymasky, Matt & Andrej (17 May 2003). “Famous GLTB: Lili Elbe”. HistoryVSHollywood.com. Archived from the original on 10 October 2007. Retrieved 2 February 2016. Based on Brown, Kay (1997); Aldrich R. & Wotherspoon G., Who’s Who in Gay and Lesbian History, from Antiquity to WWII, Routledge, London, 2001.[better source needed]

- “Lili Elbe Biography”. Biography.com. A&E Television Networks. Archived from the original on 6 January 2019. Retrieved 11 December 2015.

- A Man Changes His Sex: A Life Confession , edited from Papers Left Behind by Niels Hoyer . Translated from the Danish original Fra Mand til Kvinde by Ernst Harthern-Jacobson. Reissner, Dresden 1932, p. 15.

- “What are common symptoms of Klinefelter syndrome (KS)?”. Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. 2013-10-25. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- “Klinefelter Syndrome (KS): Overview”. nichd.nih.gov. Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. 2013-11-15. Archived from the original on 18 March 2015. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- Visootsak J, Graham JM (October 2006). “Klinefelter syndrome and other sex chromosomal aneuploidies”. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 1: 42. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-1-42. PMC 1634840. PMID 17062147.

- A 1000-year-old case of Klinefelter’s syndrome diagnosed by integrating morphology, osteology, and genetics, Xavier Roca-Rada et al, The Lancet, Volume 400, Issue 10353, 27 August 2022 – 2 September 2022, Pages 691-692

The UK and US versions of her semi-autobiographical narrative were published posthumously in 1933 under the title Man into Woman: An Authentic Record of a Change of Sex. A film inspired by her life, The Danish Girl, was released in 2015.

- Worthen, Meredith (n.d.). “Lili Elbe – Painter”. Biography.com. Archived from the original on 6 January 2019. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- Elbe, Lili (2020). Caughie, Pamela; Meyer, Sabine (eds.). Man Into Woman: A Comparative Scholarly Edition. Bloomsbury. pp. Introduction. ISBN 978-1-350-02149-5.

Early life

It is generally believed that Elbe was born in 1882, in Vejle, Denmark, the child of Ane Marie Thomsen and spice merchant Mogens Wilhelm Wegener according to the registry at St. Nicolai Church (Vejle). Her year of birth is sometimes stated as 1886, which appears to be from a book about her which has some facts changed to protect the identities of the persons involved. Facts about the life of her wife Gerda Gottlieb suggest that the 1882 date is correct because they married while at college in 1904, when Elbe would have been just eighteen if the 1886 date were correct.

- Meyer 2015, p. 340.

- “Kunstindeks Danmark & Weilbachs Kunstnerleksikon”. kulturarv.dk (in Danish). Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- She and She: The Marriage of Gerda and Einar Wegener. The Copenhagen Post. 3 July 2000

- “Ejner Mogens Wegener, 28-12-1882, Vejle Stillinger: Maler”. Politietsregisterblade.dk. Archived from the original on 3 August 2015. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

Marriage and modelling

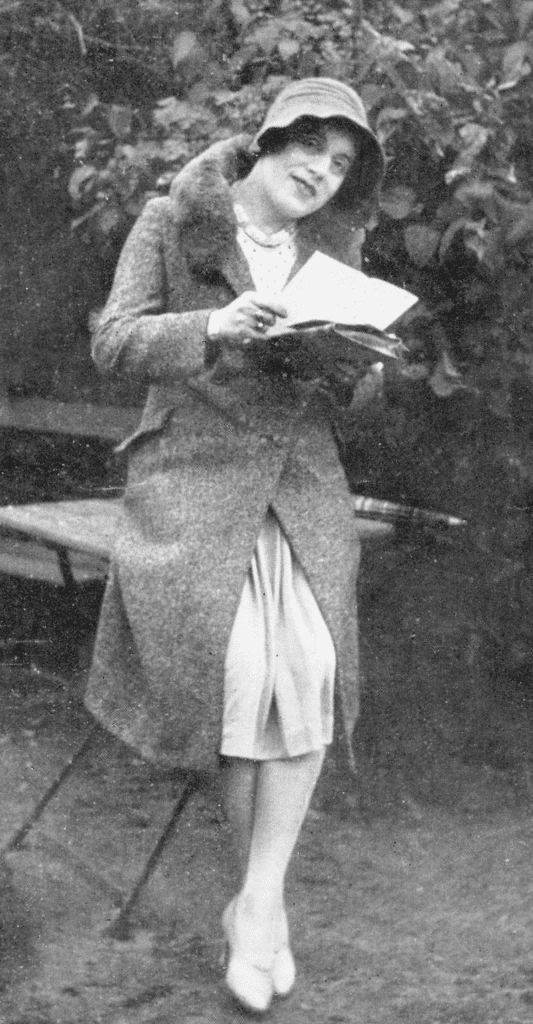

Elbe met Gerda Gottlieb while they were students at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen, and they married in 1904 when Gottlieb was 19 and Elbe was 22. Gerda came from a conservative family as her father was a vicar in the Lutheran church.

- “Conway’s Vintage Treasures”. Vintage-movie-poster.com. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 8 April 2014.

- “Biography of Gerda Wegener”. Biography.com. Archived from the original on 16 May 2019. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- “Wegener, Gerda (1886–1940) – Danish”.

They worked as illustrators, with Elbe specialising in landscape paintings while Gottlieb illustrated books and fashion magazines. They travelled through Italy and France before settling in 1912 in Paris, where Elbe could live more openly as a woman by posing as Gottlieb’s sister-in-law. Elbe received the Neuhausens prize [da] in 1907 and exhibited at Kunstnernes Efterårsudstilling (the Artists’ Fall Exhibition), at the Vejle Art Museum in Denmark, where she remains represented, and in the Saloon and Salon d’Automne in Paris.

- “Gerda Wegener: The Truth Behind The Canvas”. artefactmagazine.com. 7 March 2017. Archived from the original on 18 December 2019. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- The Arts and Transgender. renaissanceblackpool.org

Elbe started dressing in women’s clothes after she found she enjoyed the stockings and heels she wore to fill in for Gottlieb’s model, actress Anna Larssen [da], who on one occasion was late for a sitting. Larssen suggested the name Lili, and by the 1920s, Elbe regularly presented with that name as a woman, attending various festivities and entertaining guests in her house. Gottlieb became famous for her paintings of beautiful women with haunting, almond-shaped eyes, dressed in chic apparel. The model for these depictions of petites femmes fatales was Elbe. Elbe stopped painting after her transition.

- Gerda Wegener. get2net.dk

- “Lili Elbe (1886–1931)”. LGBT History Month. Archived from the original on 3 August 2015. Retrieved 8 April 2014.

- Meyer 2015, pp. 311–314

- Koymasky, Matt & Andrej (17 May 2003). “Famous GLTB: Lili Elbe”. HistoryVSHollywood.com. Archived from the original on 10 October 2007. Retrieved 2 February 2016. Based on Brown, Kay (1997); Aldrich R. & Wotherspoon G., Who’s Who in Gay and Lesbian History, from Antiquity to WWII, Routledge, London, 2001.[better source needed]

By this time, her case was a sensation in Danish and German newspapers. A Danish court annulled the couple’s marriage in October 1930, and Elbe was able to have her sex and name legally changed, including receiving a passport as Lili Ilse Elvenes. The pseudonym “Lili Elbe” was first used in a Danish newspaper article written by Copenhagen journalist Louise “Loulou” Lassen for Politiken in February 1931. Elbe returned to Dresden and began a relationship with French art dealer Claude Lejeune, whom she wanted to marry and with whom she wished to have children. Gerda was briefly married to an Italian man.

- “Lili Elbe (1886–1931)”. LGBT History Month. Archived from the original on 3 August 2015. Retrieved 8 April 2014.

- Vicente, Marta V (23 September 2021). “The Medicalization of the Transsexual: Patient-Physician Narratives in the First Half of the Twentieth Century”. Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences. 76 (4): 392–416. doi:10.1093/jhmas/jrab037. ISSN 0022-5045.

- “Lili Elbe Digital Archive”. www.lilielbe.org. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- Brown, Kay (1997) Lili Elbe. Transhistory.net.

- “A Trans Timeline – Trans Media Watch”. Trans Media Watch. Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- Meyer 2015, pp. 271–281

- Meyer 2015, pp. 308–311

- “Man Into Woman”. Archived from the original on 18 December 2019. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- Loulou Lassen (28 February 1931). “Lili Elbe Digital Archive – Contextual Material – Et Liv gennem to Tilværelser”. Politiken. Archived from the original on 2 October 2021. Retrieved 2 October 2021.

- “The Incredibly True Adventures of Gerda Wegener and Lily Elbe”. Coilhouse.net. Archived from the original on 11 May 2019. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- “Gerda Wegener – Art, Death & Facts”. Biography. 6 April 2021. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- “Lili Elbe: the transgender artist behind The Danish Girl”. This Week Magazine. 18 September 2015. Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 1 February 2016.

- Albrecht Scholz, Birgit Töpolt: The practice of forced sterilization in Dresden. ( Memento des Originals from January 10, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) In: Medical Journal Saxony. Vol. 16 (2005), no. 4, pp. 164–167 (PDF file, 139 kB). Retrieved January 10, 2016.

Elbe was buried in Trinitatisfriedhof [de] (Trinity Cemetery) in Dresden. The grave was levelled in the 1960s. In April 2016, a new tombstone was inaugurated, financed by Focus Features, the production company of The Danish Girl. The tombstone does not record the date of Elbe’s birth, just her name and places of birth and death.

- “Letzte Ehre fürs Danish Girl” [Last honor for the Danish Girl]. Queer.de (in German). 23 April 2016. Archived from the original on 21 June 2018. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- Haufe, Kay (22 April 2016). “Hollywood rettet Lili Elbes Grab” [Hollywood saves Lili Elbe’s grave]. Sächsische Zeitung (in German). Archived from the original on 21 June 2018. Retrieved 26 April 2016.

Gallery of work

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Paintings by Lili Elbe.

In popular culture

The LGBTQ+ film festival MIX Copenhagen gives four “Lili” awards named after Elbe.

- “MIX Copenhagen LGBT Film Festival – LGBTQ – Copenhagen”. ellgeeBE. Archived from the original on 9 December 2018. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

In 2000, David Ebershoff wrote The Danish Girl, a fictionalized account of Elbe’s life. It was an international bestseller and translated into many languages. This novel provided one of the earliest fictional accounts of gender affirmation surgery, which shaped LGBTQ+ literature. In 2015, it was made into a film, also called The Danish Girl, produced by Gail Mutrux and Neil LaBute, starring Eddie Redmayne as Elbe. The film was well received at the Venice Film Festival in September 2015, though it has been criticised for casting a cisgender man to play a transgender woman. Both the novel and film omitted topics, including Gottlieb’s sexuality, which is evidenced by the subjects in her erotic drawings, and the disintegration of Gottlieb and Elbe’s relationship after their annulment.

- “BOOKS OF THE TIMES; Radical Change and Enduring Love”. The New York Times. 14 February 2000. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 11 December 2015.

- “International Journal Of Arts , Humanities & Social Science”. ijahss.net. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- “The Danish Girl Wows With 10-Minute Standing Ovation In Venice Premiere”. Deadline. 5 September 2015. Archived from the original on 15 April 2019. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- Denham, Jess (12 August 2015). “The Danish Girl: Eddie Redmayne defends casting as trans artist Lili Elbe after backlash”. The Independent. Archived from the original on 12 May 2019. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- “The Incredibly True Adventures of Gerda Wegener and Lili Elbe”. coilhouse.net. 3 August 2012. Archived from the original on 11 May 2019. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- “Reading Group Notes The Danish Girl”. allenandunwin.com. Archived from the original on 24 May 2020. Retrieved 10 December 2015.

On 28 December 2022, Google Doodle celebrated Lili Elbe’s 140th birthday.

- “Lili Elbe’s 140th Birthday”. www.google.com. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- Desk, OV Digital (28 December 2022). “28 December: Google Doodle celebrates Lili Elbe’s 140th birthday”. Observer Voice. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

Tobias Picker‘s opera based-on Elbe’s life, featuring Lucia Lucas, will be premiered in 2023 at Theater St. Gallen.

- “Lili Elbe”. tobiaspicker.com. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- Charles Shafaieh. “Living Authentically”. Opera News. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- “Lili Elbe”. tobiaspicker.com.

Wow…I can’t help but wonder if all of these people know the botched surgeries that killed this person were performed by at least one decorated nazi (the castrator) who reportedly went on to perform unspeakable acts on countless others? Wikipedia data is sketchy and brief on the others which is odd considering the attention this individual has garnered. I’ve used the word insidious…and I think I’ve used it properly…but I’m inclined to think some of these people have no idea.

Publications

In 1931, Lili Elbe was living in Denmark collaborating with her friend, Ernst Harthern on a memoir of her life. Fra Mand til Kvinde was published by her German friend and editor under the name of Neils Hoyer, following Elbe’s death. The narrative provided details of her life as Danish painter and her gender confirmation surgery. The possibility of Lili Elbe being intersex has been proposed due to the narrative reporting possession of both male and female reproductive organs and the absence of medical record documenting her pre-surgical anatomy due to the Allied Bombing Raids. However, this theory has been disputed. The narrative was published four times, in three different languages over the course of two years. The UK and US versions, Man into Woman: An Authentic Record of a Change of Sex were published in 1933.

- Gailey, Nerissa (15 October 2017). “Strange Bedfellows: Anachronisms, Identity Politics, and the Queer Case of Trans*”. Journal of Homosexuality. 64 (12): 1713–1730. doi:10.1080/00918369.2016.1265355. ISSN 0091-8369. PMID 27892825.

- Worthen, Meredith (n.d.). “Lili Elbe – Painter”. Biography.com. Archived from the original on 6 January 2019. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- Elbe, Lili (2020). Caughie, Pamela; Meyer, Sabine (eds.). Man Into Woman: A Comparative Scholarly Edition. Bloomsbury. pp. Introduction. ISBN 978-1-350-02149-5.

- “Lili Elbe Digital Archive”. www.lilielbe.org. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

Man into Woman: An authentic Record of a Change of sex brought attention to new medical interventions as the story of Lili Elbe was circulated through American publications. American publications, such as “A Man Becomes a Woman” and “When Science Changed a Man into a Woman,” published in the popular magazine, Sexology, associated the story of Lili Elbe with cases of intersex sex changes. These narratives promoted a binary view of gender, reinforcing gender stereotypes among Americans.

- Meyerowitz, Joanne (1998). “Sex Change and the Popular Press: Historical Notes on Transsexuality in the United States, 1930–1955”. GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies. 4 (2): 159–187. doi:10.1215/10642684-4-2-159. ISSN 1064-2684.

Man into Woman: An authentic Record of a Change of sex and Lili Elbe became well known in European media as they were publicized by Paul Weber. The story encouraged political action and brought awareness to the challenges faced by non-gender-conforming people.

- Sutton, Katie (May 2012). “”We Too Deserve a Place in the Sun”: The Politics of Transvestite Identity in Weimar Germany”. German Studies Review. 35 (2): 335–354 – via JSTOR.

References

- Hirschfeld, Magnus. Chirurgische Eingriffe bei Anomalien des Sexuallebens: Therapie der Gegenwart, pp. 67, 451–455

- Koymasky, Matt & Andrej (17 May 2003). “Famous GLTB: Lili Elbe”. HistoryVSHollywood.com. Archived from the original on 10 October 2007. Retrieved 2 February 2016. Based on Brown, Kay (1997); Aldrich R. & Wotherspoon G., Who’s Who in Gay and Lesbian History, from Antiquity to WWII, Routledge, London, 2001.[better source needed]

- Meyer 2015, pp. 15, 310–313.

- Meyer 2015, pp. 311–314

- Goldberg, A.E.; Beemyn, G. (2021). The SAGE Encyclopedia of Trans Studies. SAGE Publications. p. 261. ISBN 978-1-5443-9382-7. Retrieved 12 January 2023.

- Kroløkke, C.; Petersen, T.S.; Herrmann, J.R.; Bach, A.S.; Adrian, S.W.; Klingenberg, R.; Petersen, M.N. (2019). The Cryopolitics of Reproduction on Ice: A New Scandinavian Ice Age. Emerald Studies in Reproduction, Culture and Society. Emerald Publishing Limited. p. 154. ISBN 978-1-83867-044-3. Retrieved 31 January 2023.

- “Lili Elbe Biography”. Biography.com. A&E Television Networks. Archived from the original on 6 January 2019. Retrieved 11 December 2015.

- “Lili Elbe: the transgender artist behind The Danish Girl“. This Week Magazine. 18 September 2015. Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 1 February 2016.

- “The Danish Girl (2015)”. HistoryVSHollywood.com. History vs Hollywood. Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 1 February 2016.[better source needed]

- Worthen, Meredith (n.d.). “Lili Elbe – Painter”. Biography.com. Archived from the original on 6 January 2019. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- Elbe, Lili (2020). Caughie, Pamela; Meyer, Sabine (eds.). Man Into Woman: A Comparative Scholarly Edition. Bloomsbury. pp. Introduction. ISBN 978-1-350-02149-5.

- Meyer 2015, p. 340.

- “Kunstindeks Danmark & Weilbachs Kunstnerleksikon”. kulturarv.dk (in Danish). Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- She and She: The Marriage of Gerda and Einar Wegener. The Copenhagen Post. 3 July 2000

- “Ejner Mogens Wegener, 28-12-1882, Vejle Stillinger: Maler”. Politietsregisterblade.dk. Archived from the original on 3 August 2015. Retrieved 30 December 2011.

- Hoyer, Niels, ed. (2004). Man into woman: the first sex change, a portrait of Lili Elbe: the true and remarkable transformation of the painter Einar Wegener. London: Blue Boat Books. pp. vii, 26–27, 172. ISBN 978-0-9547072-0-0.

- “Lili Elbe’s autobiography, Man into Woman“. OII Australia – Intersex Australia. OII Australia. 16 April 2009. Archived from the original on 28 March 2015. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- Vacco, Patrick (29 April 2014). “Les Miserables Actor Eddie Redmayne to Star as Queer Artist Lili Elbe”. The Advocate. Archived from the original on 29 September 2015. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- Kaufmann, Jodi (January 2007). “Transfiguration: a narrative analysis of male‐to‐female transsexual”. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education. 20 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1080/09518390600923768. S2CID 144939698.

- “Conway’s Vintage Treasures”. Vintage-movie-poster.com. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019. Retrieved 8 April 2014.

- “Biography of Gerda Wegener”. Biography.com. Archived from the original on 16 May 2019. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- “Wegener, Gerda (1886–1940) – Danish”.

- “Gerda Wegener: The Truth Behind The Canvas”. artefactmagazine.com. 7 March 2017. Archived from the original on 18 December 2019. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- The Arts and Transgender. renaissanceblackpool.org

- Gerda Wegener. get2net.dk

- “Lili Elbe (1886–1931)”. LGBT History Month. Archived from the original on 3 August 2015. Retrieved 8 April 2014.

- Vicente, Marta V (23 September 2021). “The Medicalization of the Transsexual: Patient-Physician Narratives in the First Half of the Twentieth Century”. Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences. 76 (4): 392–416. doi:10.1093/jhmas/jrab037. ISSN 0022-5045.

- “Lili Elbe Digital Archive”. www.lilielbe.org. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- Brown, Kay (1997) Lili Elbe. Transhistory.net.

- “A Trans Timeline – Trans Media Watch”. Trans Media Watch. Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- Meyer 2015, pp. 271–281

- Meyer 2015, pp. 308–311

- “Man Into Woman“. Archived from the original on 18 December 2019. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- Loulou Lassen (28 February 1931). “Lili Elbe Digital Archive – Contextual Material – Et Liv gennem to Tilværelser”. Politiken. Archived from the original on 2 October 2021. Retrieved 2 October 2021.

- “The Incredibly True Adventures of Gerda Wegener and Lily Elbe”. Coilhouse.net. Archived from the original on 11 May 2019. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- “Gerda Wegener – Art, Death & Facts”. Biography. 6 April 2021. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- Harrod, Horatia (8 December 2015). “The tragic true story behind The Danish Girl“. The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 21 April 2016. Retrieved 11 December 2015.

- “Lili Elbe (Einar Wegener) 1882–1931”. Danmarkshistorien.dk (in Danish). Danmarkshistorien.dk. 10 September 2013. Archived from the original on 5 April 2016. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- “Letzte Ehre fürs Danish Girl“ [Last honor for the Danish Girl]. Queer.de (in German). 23 April 2016. Archived from the original on 21 June 2018. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- Haufe, Kay (22 April 2016). “Hollywood rettet Lili Elbes Grab” [Hollywood saves Lili Elbe’s grave]. Sächsische Zeitung (in German). Archived from the original on 21 June 2018. Retrieved 26 April 2016.

- “MIX Copenhagen LGBT Film Festival – LGBTQ – Copenhagen”. ellgeeBE. Archived from the original on 9 December 2018. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

- “BOOKS OF THE TIMES; Radical Change and Enduring Love”. The New York Times. 14 February 2000. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 11 December 2015.

- “International Journal Of Arts , Humanities & Social Science”. ijahss.net. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- “The Danish Girl Wows With 10-Minute Standing Ovation In Venice Premiere”. Deadline. 5 September 2015. Archived from the original on 15 April 2019. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- Denham, Jess (12 August 2015). “The Danish Girl: Eddie Redmayne defends casting as trans artist Lili Elbe after backlash”. The Independent. Archived from the original on 12 May 2019. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- “The Incredibly True Adventures of Gerda Wegener and Lili Elbe”. coilhouse.net. 3 August 2012. Archived from the original on 11 May 2019. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- “Reading Group Notes The Danish Girl“. allenandunwin.com. Archived from the original on 24 May 2020. Retrieved 10 December 2015.

- “Lili Elbe’s 140th Birthday”. www.google.com. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- Desk, OV Digital (28 December 2022). “28 December: Google Doodle celebrates Lili Elbe’s 140th birthday”. Observer Voice. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- “Lili Elbe”. tobiaspicker.com. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- Charles Shafaieh. “Living Authentically”. Opera News. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- “Lili Elbe”. tobiaspicker.com.

- Gailey, Nerissa (15 October 2017). “Strange Bedfellows: Anachronisms, Identity Politics, and the Queer Case of Trans*”. Journal of Homosexuality. 64 (12): 1713–1730. doi:10.1080/00918369.2016.1265355. ISSN 0091-8369. PMID 27892825.

- Meyerowitz, Joanne (1998). “Sex Change and the Popular Press: Historical Notes on Transsexuality in the United States, 1930–1955”. GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies. 4 (2): 159–187. doi:10.1215/10642684-4-2-159. ISSN 1064-2684.

- Sutton, Katie (May 2012). “”We Too Deserve a Place in the Sun”: The Politics of Transvestite Identity in Weimar Germany”. German Studies Review. 35 (2): 335–354 – via JSTOR.

Bibliography

- Meyer, Sabine (2015). “Wie Lili zu einem richtigen Mädchen wurde”: Lili Elbe: Zur Konstruktion von Geschlecht und Identität zwischen Medialisierung, Regulierung und Subjektivierung. transcript Verlag. ISBN 978-3-8394-3180-1.

Further reading

- Man into woman: an authentic record of a change of sex / Lili Elbe; edited by Niels Hoyer [i.e. E. Harthern]; translated from the German by H.J. Stenning; introd. by Norman Haire. London: Jarrold Publishers, 1933 (Original Danish ed. published in 1931 under title: Fra mand til kvinde. Later edition: Man into woman: the first sex change, a portrait of Lili Elbe – the true and remarkable transformation of the painter Einar Wegener. London: Blue Boat Books, 2004.

- Schnittmuster des Geschlechts. Transvestitismus und Transsexualität in der frühen Sexualwissenschaft by Dr. Rainer Herrn (2005), pp. 204–211. ISBN 3-89806-463-8. German study containing a detailed account of the operations of Lili Elbe, their preparations and the role of Magnus Hirschfeld.

- “When a woman paints women” / Andrea Rygg Karberg and “The transwoman as model and co-creator: resistance and becoming in the back-turning Lili Elbe” / Tobias Raun in Gerda Wegener / edited by Andrea Rygg Karberg … [et al.]. – Denmark, Arken Museum of Modern Art, 2015.

External links

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lili Elbe.

- Lili Elbe on Biography.com

- Lili Elbe on LGBT History Month

- Lili Elbe Digital Archive

- From the doll’s pram into normative femininity. Lili Elbe and the journalistic staging of transsexuality in Denmark German journal article. NORDEUROPAforum 20 (2010:1–2), 33–61

- Represented in ARKEN Museum of Modern Art’s Gerda Wegener exhibition November 2015 – January 2017

- 1882 births

- 1931 deaths

- 20th-century Danish painters

- Danish erotic artists

- Danish landscape painters

- Intersex women

- Danish LGBT artists

- Transgender memoirists

- Danish transgender people

- People from Vejle Municipality

- Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts alumni

- Transgender painters

- Transgender women

- Uterus transplant recipients

Leave a Reply