In classical Greek mythology, Syrinx was a nymph and a follower of Artemis, known for her chastity

Mythology

Story

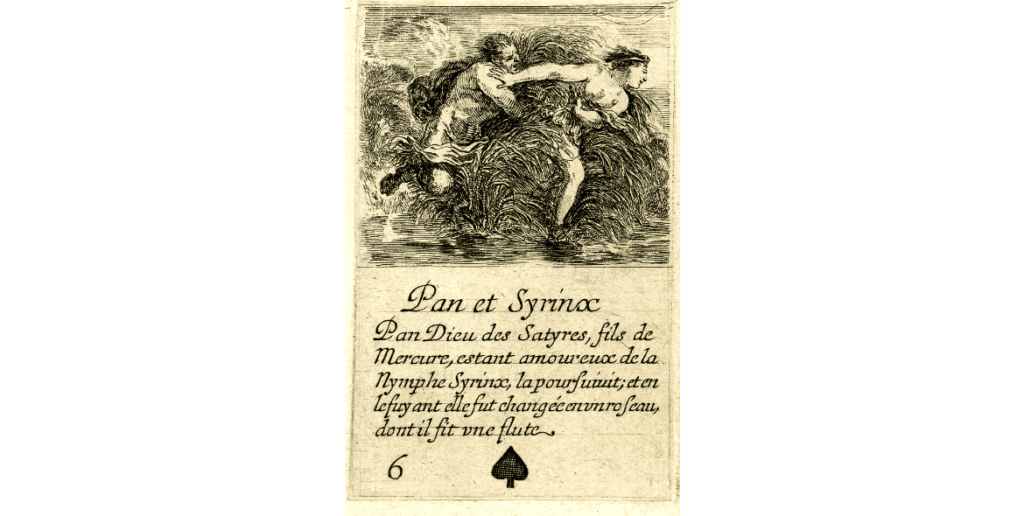

Syrinx was a beautiful wood nymph who had many times attracted the attention of satyrs, and fled their advances in turn. She worshipped Artemis, the goddess of wilderness, and had like her vowed to remain a virgin for all time. Pursued by the amorous god Pan, she ran to a river’s edge and asked for assistance from the river nymphs. In answer, she was transformed into hollow water reeds that made a haunting sound when the god’s frustrated breath blew across them. Pan cut the reeds to fashion the first set of panpipes, which were thenceforth known as syrinx.

The word syringe was derived from this word.

syringe (n.)

“narrow tube for injecting a stream of liquid,” early 15c. (earlier suringa, late 14c.), from Late Latin syringa, from Greek syringa, accusative of syrinx “tube, hole, channel, shepherd’s pipe,” related to syrizein “to pipe, whistle, hiss,” from PIE root *swer- (see susurration). Originally a catheter for irrigating wounds; the application to hypodermic needles is from 1884. Related: Syringeal.

“a whispering, a murmur,” c. 1400, susurracioun, from Latin susurrationem (nominative susurratio), noun of action from past-participle stem of susurrare “to hum, murmur,” from susurrus “a murmur, whisper.” This is held to be a reduplication of a PIE imitative *swer- “to buzz, whisper” (source also of Sanskrit svarati “sounds, resounds,” Greek syrinx “flute,” Latin surdus “dull, mute,” Old Church Slavonic svirati “to whistle,” Lithuanian surma “pipe, shawm,” German schwirren “to buzz,” Old English swearm “a swarm”).

tubular instrument, c. 1600, the thing itself known from 14c. in English, from Late Latin syrinx, from Greek syrinx “shepherd’s pipe” (see syringe). Used of vocal organs of birds from 1872.

- Harper, Douglas. “Etymology of syringe.” Online Etymology Dictionary, https://www.etymonline.com/word/syringe. Accessed 13 April, 2023.

Authors

Ovid includes the story of Pan and Syrinx in Book One of the Metamorphoses, where it is told by Mercury to Argus in the course of lulling him asleep in order to kill him. The myth is also preserved in the works of some anonymous paradoxographer.

- Anton Westermann, Paradoxographers anonymous, p. 222, 1839.

The story is also told in Achilles Tatius‘ Leukippe and Kleitophon where the heroine is subjected to a virginity test by entering a cave where Pan has left syrinx pipes that will sound a melody if she passes. This has similarities with another myth Achilles wrote down, that of Rhodopis, who was transformed into a fountain that served as a virginity testing place for maidens.

- Reardon, B.P. “Leucippe and Clitophon.” Trans. John J. Winkler Collected Ancient Greek Novels. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008. 272-273.

- Forbes Irving, Paul M. C. (1990). Metamorphosis in Greek Myths. Clarendon Press. p. 306. ISBN 0-19-814730-9.

Longus makes reference to Syrinx in his tale of “Daphnis and Chloe” in Book 2:34. Whilst the description of the tale here is modified to that of Ovid, it nevertheless incorporates Pan‘s desire to have her. Longus, however, makes no reference to Syrinx receiving aid from the Nymphs in his version, instead Syrinx hides from Pan in amongst some reeds and disappears into the marsh. Upon realising what had happened to Syrinx, Pan created the first set of panpipes from the reeds she was transformed into, allowing her to be with him for the rest of his days.

In literature

The story became popular among artists and writers in the 19th century. Elizabeth Barrett Browning wrote a poem entitled “A Musical Instrument” describing Pan’s ruinous actions in creating the musical pipes. The Victorian artist and poet Thomas Woolner wrote Silenus, a long narrative poem about the myth, in which Syrinx becomes the lover of Silenus, but drowns when she attempts to escape rape by Pan. As a result of the crime, Pan is transmuted into a demon figure and Silenus becomes a drunkard. Amy Clampitt‘s poem Syrinx refers to the myth by relating the whispering of the reeds to the difficulties of language.

- Thomas Woolner, Silenus, Macmillan, 1884.

The story was used as a central theme by Aifric Mac Aodha in her poetry collection Gabháil Syrinx.

Samuel R. Delany features an instrument called a syrynx in his science-fiction novel Nova.

Syrinx is the name of one of the main characters in the Night’s Dawn Trilogy of space opera novels by British author Peter F. Hamilton. In the trilogy, Syrinx is a member of the transhumanist future society known as Edenism, and serves as the captain of the Oenone, a living starship.

A 1972 poem by James Merrill, titled “Syrinx”, draws on several aspects on the mythological tale, with the poet himself identifying with the celebrated nymph, desiring to become not just a “reed” but a “thinking reed” (in contrast to a “thinking stone”, as critic Helen Vendler has observed, noting the influence of a Wallace Stevens lyric, “Le Monocle de Mon Oncle”). The poet aspires to return to his “scarred case” with minimal suffering inflicted by “the great god Pain”, a play of words on the Greek god Pan. “Syrinx” is the final poem in Merrill’s 1972 collection, Braving the Elements.

- Vendler, Helen (September 24, 1972). “New Merrill”. The New York Times. Retrieved March 25, 2017.

In philosophy

In Dark Places of Wisdom, Peter Kingsley discusses in some detail the use of the word in Parmenides‘ poem and in association with the ancient practice of incubation

- pages 101-135, but especially pages 116ff on “The Sound of Piping”. Also pages 3–5 of Excerpts from In the Dark Places of Wisdom and Reality, by Peter Kingsley Archived 2015-03-15 at the Wayback Machine

In art

Pan and Syrinx by Jean-François de Troy, 1722-1724

The British Victorian artist Arthur Hacker depicted Syrinx in his 1892 nude. This painting in oil on canvas is currently on display in Manchester Art Gallery.

A sculpture of Syrinx created in 1925 by sculptor William McMillan is displayed at the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum in Glasgow.

Sculptor Adolph Wolter was commissioned in 1973 to create a replacement for a stolen sculpture of Syrinx in Indianapolis, United States. This work was a replacement for a similar statue by Myra Reynolds Richards that had been stolen. The sculpture sits in University Park located in the city’s Indiana World War Memorial Plaza.

Abraham Jannsens painted Syrinx in 1620 as part of “Pan and Syrinx”.

In music

Claude Debussy‘s Syrinx. Performed by Sarah Bassingthwaighte

Problems playing this file? See media help.

Claude Debussy based his 1913 Syrinx (Debussy) on Pan’s sadness over losing his love. The piece is still popular today; it was used as incidental music in the play Psyché by Gabriel Mourey.

- James McCalla, Twentieth-century Chamber Music: Routledge Studies in Musical Genres, Routledge, 2003, p.48

Maurice Ravel incorporated the character of the Syrinx into his ballet Daphnis et Chloé.

Gustav Holst alludes to the story of Pan and Syrinx in the opening of his Choral Symphony, which draws from the text of John Keats’ 1818 poem “Endymion.”

French Baroque composer Michel Pignolet de Montéclair composed “Pan et Syrinx”, a cantata for voice and ensemble (No. 4 of Second livre de cantates).

Danish composer Carl Nielsen composed Pan and Syrinx (Pan og Syrinx), Op. 49, FS 87.

- Canadian electronic progressive rock band Syrinx took their name from the legend.

Canadian progressive rock band Rush have a movement titled “The Temples of Syrinx” in their song “2112” on their album 2112. The song is about a dystopian futuristic society in which the arts, particularly music, have been suppressed by the Priests of the Temples of Syrinx.

Related to the Rush reference, Maryland based rockers Clutch mention the Temples of Syrinx in their song “10001110101” from their album Robot Hive/Exodus.

References

- Ovid, Metamorphoses 1.689ff

- Anton Westermann, Paradoxographers anonymous, p. 222, 1839.

- Reardon, B.P. “Leucippe and Clitophon.” Trans. John J. Winkler Collected Ancient Greek Novels. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008. 272-273.

- Forbes Irving, Paul M. C. (1990). Metamorphosis in Greek Myths. Clarendon Press. p. 306. ISBN 0-19-814730-9.

- Thomas Woolner, Silenus, Macmillan, 1884.

- Vendler, Helen (September 24, 1972). “New Merrill”. The New York Times. Retrieved March 25, 2017.

- pages 101-135, but especially pages 116ff on “The Sound of Piping”. Also pages 3–5 of Excerpts from In the Dark Places of Wisdom and Reality, by Peter Kingsley Archived 2015-03-15 at the Wayback Machine

- James McCalla, Twentieth-century Chamber Music: Routledge Studies in Musical Genres, Routledge, 2003, p.48

- “CLUTCH”.

Further reading

- Greppin, John A. C. (1990). “The Etymology of Greek Σῦριγξ ‘Pipe'”. Historische Sprachforschung [Historical Linguistics]. 103 (1): 35–37. JSTOR 40848933. Accessed 19 Feb. 2023.

See also

- 3360 Syrinx – an asteroid named after Syrinx

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Syrinx.

Leave a Reply