In architecture and sculpture, a pluteus (plural plutei) is a balustrade made up of massive rectangular slabs of wood, stone or metal, which divides part of a building in half; in a church they fulfil the same function as an iconostasis or rood screen, separating the nave from the chancel.

- “Plùteo” (in Italian). Vocabolario Treccani online.

- Bruno Maria Apollonj Ghetti. “Pluteo”. www.treccani.it (in Italian). Enciclopedia Italiana (1935)

They are decorated with frames in relief or richly decorated with figures or geometric motifs.

One set of examples is the so-called Plutei of Trajan, discovered between the Comitium and the Column of Phocas in the Roman Forum in 1872 and another is the Plutei of Theodota.

The Plutei of Theodota are two mid 8th-century Lombard marble bas-reliefs or plutei from the oratory of San Michele alla Pusterla in Italy. They are now held in the Civic Museums of Pavia. Naturalistic in style, they were produced during the Liutprandean Renaissance. One shows the Tree of Life between two griffins and the other shows a cross and font between two peacocks.

- (in Italian) Lida Capo, ‘Commento’ in Paolo Diacono, Storia dei Longobardi, pp. 556-557.

- (in Italian) Pierluigi De Vecchi, Elda Cerchiari, ‘I Longobardi in Italia’, in L’arte nel tempo, Milano, Bompiani, 1991, Vol. 1, tomo II, pp. 305-317., ISBN 88-450-4219-7

- (in Italian) Pierluigi De Vecchi-Elda Cerchiari, I Longobardi in Italia, p. 311.

They are named after Theodota, a Byzantine noblewoman who became the lover of king Cunipert (688–700), who later placed her in the Santa Maria Teodote monastery, also known as Santa Maria della Pusterla (now the Diocesan Seminary for Pavia), near which was later built the oratorio di San Michele.

- (in Italian) Lida Capo, ‘Commento’ in Paolo Diacono, Storia dei Longobardi, pp. 556-557.

- (in Latin) Paolo Diacono, Historia Langobardorum, V, 37 in Georg Waitz, ed. (1878). Monumenta Germaniae Historica. p. Scriptores rerum Langobardicarum et Italicarum saec. VI–IX, 12–219.

The Plutei of Trajan

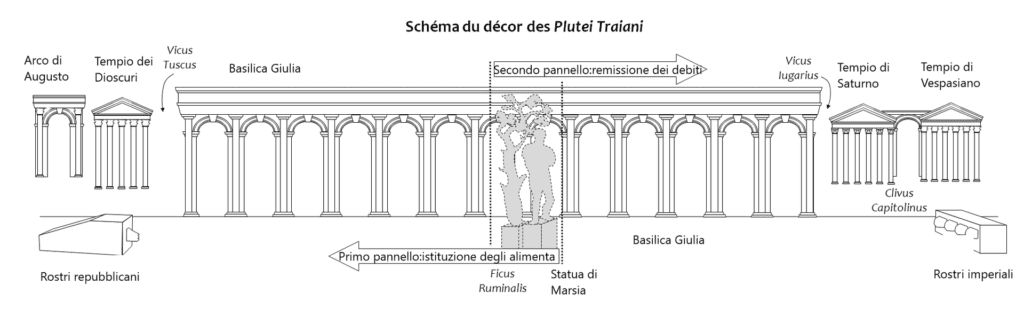

The Plutei of Trajan (Latin Plutei Traiani; often called the Anaglypha Traiani) are carved stone balustrades built for the Roman emperor Trajan. They are on display inside the Curia Julia in the Roman Forum today, but are not part of the original structure.

It is unknown exactly where Trajan erected them. They are believed to have been built either on the edge of the Rostra or on the sides of the Lapis Niger marking the underground “Tomb of Romulus”. In spite of this uncertainty, they are of great historical value because the carvings show the full length of both sides of the Forum at the time they were erected.

The rostra (Italian: Rostri) was a large platform built in the city of Rome that stood during the republican and imperial periods. Speakers would stand on the rostra and face the north side of the comitium towards the senate house and deliver orations to those assembled in between. It is often referred to as a suggestus or tribunal, the first form of which dates back to the Roman Kingdom, the Vulcanal.

- Nichols, Francis Morgan (1877). The Roman Forum. London. Longmans and Co. pp. 196. ISBN 978-1-4373-2096-1.

- Richardson, Lawrence (1992). A new topographical dictionary of ancient Rome. The Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 400. ISBN 978-0-8018-4300-6.

- Lanciani, Rodolfo Amedeo (1900). The ruins and excavations of ancient Rome. Bell Publishing Company (1979). p. 278. ISBN 0-517-28945-8.

- O’Connor, Charles James (1904). The Graecostasis of the Roman forum and its vicinity. University of Wisconsin. p. 183. ISBN 978-1-104-39141-6.

The Lapis Niger (Latin, “Black Stone”) is an ancient shrine in the Roman Forum. Together with the associated Vulcanal (a sanctuary to Vulcan) it constitutes the only surviving remnants of the old Comitium, an early assembly area that preceded the Forum and is thought to derive from an archaic cult site of the 7th or 8th century BC. The black marble paving (1st century BC) and modern concrete enclosure (early 20th century) of the Lapis Niger overlie an ancient altar and a stone block with one of the earliest known Old Latin inscriptions (c. 570–550 BC).

The site is believed to date back to the Roman regal period. The inscription includes the word rex, probably referring to either a king (rex), or to the rex sacrorum, a high religious official. At some point, the Romans forgot the original significance of the shrine. This led to several conflicting stories of its origin. Romans believed the Lapis Niger marked either the grave of the first king of Rome, Romulus, or the spot where he was murdered by the Senate; the grave of Hostus Hostilius, grandfather of King Tullus Hostilius; or the location where Faustulus, foster father of Romulus, fell in battle. The earliest writings referring to this spot regard it as a suggestum where the early kings of Rome would speak to the crowds at the forum and to the Senate. The two altars are common at shrines throughout the early Roman or late Etruscan period. The Lapis Niger is mentioned in an uncertain and ambiguous way by several writers of the early Imperial period: Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Plutarch, and Festus. They do not seem to know which old stories about the shrine should be believed.

- Festus, De verborum significatu s.v. lapis niger.

Description

Foreground carvings

The relief on the right side shows Trajan in the Forum Romanum, where he institutes a charitable organisation for orphans (known as the alimenta). Trajan is seated on a podium in the middle of the Forum, together with a personification of Italia carrying a child on her arm.

The left relief shows the destruction of tax records in the presence of the emperor, probably Hadrian in 118, to the tune of 900 million sesterces. The wooden tablets with the tax records are carried forth and burned in the presence of the emperor, who is standing in front of the Rostra. The practice of “fiscal pardon” had been carried out previously under Trajan following his victory in the First Dacian War in 102.

Background carvings

The backgrounds of both the right and left sides depict buildings on the Forum Romanum.

On the right relief, depicted left to right, the buildings are: The Ficus Ruminalis and the statue of Marsyas; the Basilica Julia; the Temple of Saturn; the Temple of Vespasian and Titus; and the Rostra (only one of which is visible). A part of the relief is missing, where the Temple of Concord should have been.

On the left, again from left to right: the speakers’ platform in front of the Temple of Divus Julius; the Arch of Augustus; the Temple of Castor and Pollux; the Vicus Tuscus; the Basilica Julia; the Ficus Ruminalis and the statue of Marsyas.

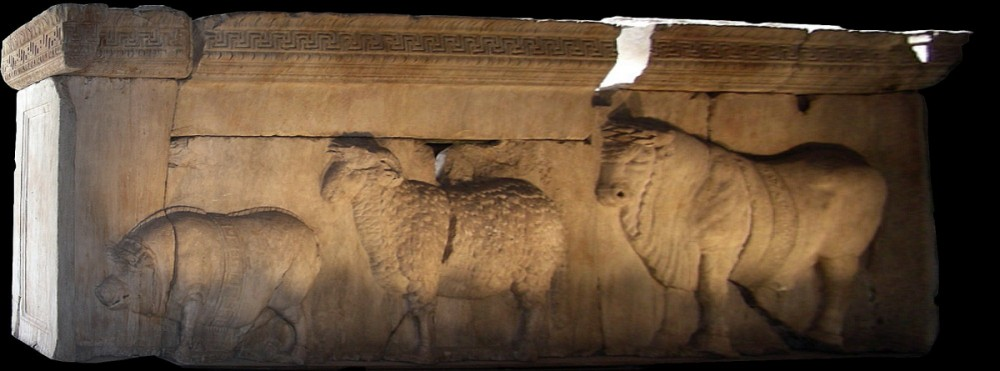

The suovetaurilia or suovitaurilia was one of the most sacred and traditional rites of Roman religion: the sacrifice of a pig (sus), a sheep (ovis) and a bull (taurus) to the deity Mars to bless and purify land (Lustratio).

- How to Be a Farmer: An Ancient Guide to Life on the Land. Princeton University Press. 2021-11-02. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-691-22473-2.

- Dillon, Matthew; Garland, Lynda (2013-10-28). Ancient Rome: A Sourcebook. Routledge. p. 129. ISBN 978-1-136-76143-0.

- Greenley, Ben; Menashe, Dan; Renshaw, James (2017-07-13). OCR Classical Civilisation GCSE Route 1: Myth and Religion. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 61. ISBN 978-1-350-01489-3.

There were two kinds:

- suovetaurilia lactentia (“suckling suovetaurilia”) of a male pig, a lamb and a calf, for purifying private fields

- suovetaurilia maiora (“greater suovtaurilia”) of a boar, a ram and a bull, for public ceremonies.

- Linderski, J. (7 March 2016). “suovetaurilia”. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Classics. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.013.6149. ISBN 978-0-19-938113-5. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- Orlin, Eric (2015-11-19). Routledge Encyclopedia of Ancient Mediterranean Religions. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-62559-8.

A private rural suovetaurilia was sacrificed each May on the festival of Ambarvalia, a festival that involved “walking around the fields.” Public suovetaurilias were offered at certain state ceremonies, including agricultural festivals, the conclusion of a census, and to atone for any accidental ritual errors. Traditionally, suovetaurilias were performed at five year intervals: this period was called a lustrum, and the purification sought by a suovetaurilia was called lustration.

- Pascal, C. Bennett (1988). “Tibullus and the Ambarvalia”. The American Journal of Philology. 109 (4): 523–536. doi:10.2307/295078. ISSN 0002-9475. JSTOR 295078.

- Gagarin, Michael (2009-12-31). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome. Oxford University Press. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-19-517072-6.

- Bagnall, Roger S; Brodersen, Kai; Champion, Craige B; Erskine, Andrew; Huebner, Sabine R, eds. (2013-01-21). The Encyclopedia of Ancient History (1 ed.). Wiley. doi:10.1002/9781444338386.wbeah17026.pub2. ISBN 978-1-4051-7935-5. S2CID 241398302.

- Sexton, Jeremy (2017). “”Brass” Instruments and Romanization: Tubae and Cornua on the Arch at Susa” (PDF). Historic Brass Journal. 29. doi:10.2153/0120170011003 (inactive 2023-01-30).

- Galinsky, Karl; Lapatin, Kenneth (2016-01-01). Cultural Memories in the Roman Empire. Getty Publications. p. 240. ISBN 978-1-60606-462-7.

- Hitch, Sarah; Rutherford, Ian (2017-08-24). Animal Sacrifice in the Ancient Greek World. Cambridge University Press. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-521-19103-6.

- Poccetti, Paolo (2016-12-05). Latinitatis rationes: Descriptive and Historical Accounts for the Latin Language. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. pp. 142–143. ISBN 978-3-11-043189-6.

On Trajan’s column, the emperor Trajan is depicted as offering a suovetaurilia to purify the Roman army. A suovetaurilia is shown on the right hand panel of The Bridgeness Slab. It was suggested that the sacrifice might have been made at the start of the building of the Antonine Wall.

- The Scottish antiquary, or, Northern notes & queries. Edinburgh: T. and A. Constable. 1890. pp. 19–25. Retrieved 28 October 2017.

Parallels

Some religious rites similar to the Roman suovetaurilia were practiced by a few other Indo-European peoples, from Iberia to India. The Cabeço das Fráguas inscript (found in Portugal) describes a threefold sacrifice practiced by the Lusitanians, devoting a sheep, a pig and a bull to what may have been local gods. In the Indian Sautramani, a ram, a bull and a goat were sacrificed to Indra Sutraman; in Iran ten thousand sheep, a thousand cattle and a hundred stallions were dedicated to Ardvi Sura Anahita. Similar to the above rituals is the Greek trittoíai, the oldest known being described in the Odyssey and dedicated to Poseidon. The philosopher and historian Plutarch related in the Lives Of The Noble Greeks And Romans a story from the life of Pyrrhus about the sacrifice of a ram, a pig and a bull. The Umbrian Iguvine Tables also describe a sacrificial ritual related to the aforementioned rites.

- Blanca María Prósper (1999). “The inscription of Cabeço das Fraguas revisited. Lusitanian and Alteuropäisch populations in the west of the Iberian Peninsula”. Transactions of the Philological Society. 97 (2): 151-184. doi:10.1111/1467-968X.00047.

References

- “Plùteo” (in Italian). Vocabolario Treccani online.

- Bruno Maria Apollonj Ghetti. “Pluteo”. www.treccani.it (in Italian). Enciclopedia Italiana (1935).

- (in Italian) Lida Capo, ‘Commento’ in Paolo Diacono, Storia dei Longobardi, pp. 556-557.

- (in Italian) Pierluigi De Vecchi, Elda Cerchiari, ‘I Longobardi in Italia’, in L’arte nel tempo, Milano, Bompiani, 1991, Vol. 1, tomo II, pp. 305-317., ISBN 88-450-4219-7

- (in Italian) Pierluigi De Vecchi-Elda Cerchiari, I Longobardi in Italia, p. 311.

- (in Latin) Paolo Diacono, Historia Langobardorum, V, 37 in Georg Waitz, ed. (1878). Monumenta Germaniae Historica. p. Scriptores rerum Langobardicarum et Italicarum saec. VI–IX, 12–219.

- How to Be a Farmer: An Ancient Guide to Life on the Land. Princeton University Press. 2021-11-02. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-691-22473-2.

- Dillon, Matthew; Garland, Lynda (2013-10-28). Ancient Rome: A Sourcebook. Routledge. p. 129. ISBN 978-1-136-76143-0.

- Greenley, Ben; Menashe, Dan; Renshaw, James (2017-07-13). OCR Classical Civilisation GCSE Route 1: Myth and Religion. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 61. ISBN 978-1-350-01489-3.

- Blanca María Prósper (1999). “The inscription of Cabeço das Fraguas revisited. Lusitanian and Alteuropäisch populations in the west of the Iberian Peninsula”. Transactions of the Philological Society. 97 (2): 151-184. doi:10.1111/1467-968X.00047.

- Linderski, J. (7 March 2016). “suovetaurilia”. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Classics. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.013.6149. ISBN 978-0-19-938113-5. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- Orlin, Eric (2015-11-19). Routledge Encyclopedia of Ancient Mediterranean Religions. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-62559-8.

- Pascal, C. Bennett (1988). “Tibullus and the Ambarvalia”. The American Journal of Philology. 109 (4): 523–536. doi:10.2307/295078. ISSN 0002-9475. JSTOR 295078.

- Gagarin, Michael (2009-12-31). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome. Oxford University Press. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-19-517072-6.

- Bagnall, Roger S; Brodersen, Kai; Champion, Craige B; Erskine, Andrew; Huebner, Sabine R, eds. (2013-01-21). The Encyclopedia of Ancient History (1 ed.). Wiley. doi:10.1002/9781444338386.wbeah17026.pub2. ISBN 978-1-4051-7935-5. S2CID 241398302.

- Sexton, Jeremy (2017). “”Brass” Instruments and Romanization: Tubae and Cornua on the Arch at Susa” (PDF). Historic Brass Journal. 29. doi:10.2153/0120170011003 (inactive 2023-01-30).

- Galinsky, Karl; Lapatin, Kenneth (2016-01-01). Cultural Memories in the Roman Empire. Getty Publications. p. 240. ISBN 978-1-60606-462-7.

- Hitch, Sarah; Rutherford, Ian (2017-08-24). Animal Sacrifice in the Ancient Greek World. Cambridge University Press. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-521-19103-6.

- Poccetti, Paolo (2016-12-05). Latinitatis rationes: Descriptive and Historical Accounts for the Latin Language. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. pp. 142–143. ISBN 978-3-11-043189-6.

- The Scottish antiquary, or, Northern notes & queries. Edinburgh: T. and A. Constable. 1890. pp. 19–25. Retrieved 28 October 2017.

- Nichols, Francis Morgan (1877). The Roman Forum. London. Longmans and Co. pp. 196. ISBN 978-1-4373-2096-1.

- Richardson, Lawrence (1992). A new topographical dictionary of ancient Rome. The Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 400. ISBN 978-0-8018-4300-6.

- Lanciani, Rodolfo Amedeo (1900). The ruins and excavations of ancient Rome. Bell Publishing Company (1979). p. 278. ISBN 0-517-28945-8.

- O’Connor, Charles James (1904). The Graecostasis of the Roman forum and its vicinity. University of Wisconsin. p. 183. ISBN 978-1-104-39141-6.

- Festus, De verborum significatu s.v. lapis niger.

Other References

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Plutei of Trajan.

Leave a Reply