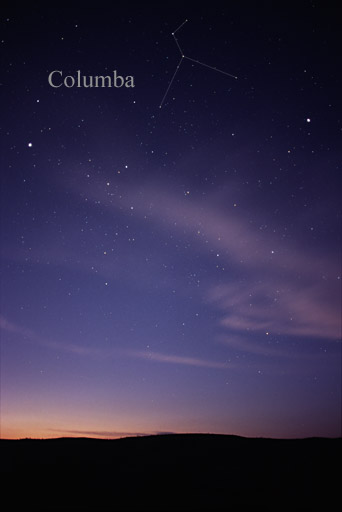

Columba constellation

Columba is a faint constellation designated in the late sixteenth century, remaining in official use, with its rigid limits set in the 20th century. Its name is Latin for dove. It takes up 1.31% of the southern celestial hemisphere and is just south of Canis Major and Lepus.

History

Early 3rd century BC: Aratus‘s astronomical poem Phainomena (lines 367–370 and 384–385) mentions faint stars where Columba is now but does not fit any name or figure to them.

2nd century AD: Ptolemy listed 48 constellations in the Almagest but did not mention Columba.

c. 150–215 AD: Clement of Alexandria wrote in his Logos Paidogogos “Αἱ δὲ σφραγῖδες ἡμῖν ἔστων πελειὰς ἢ ἰχθὺς ἢ ναῦς οὐριοδρομοῦσα ἢ λύρα μουσική, ᾗ κέχρηται Πολυκράτης, ἢ ἄγκυρα ναυτική,” (“[when recommending symbols for Christians to use], let our seals be a dove or a fish or a ship running in a good wind or a musical lyre … or a ship’s anchor …”), with no mention of stars or astronomy.

- B. Schildgen (2016). Heritage or Heresy: Preservation and Destruction of Religious Art and Architecture in Europe. Springer. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-230-61315-7.

1592 AD: Petrus Plancius first depicted Columba on the small celestial planispheres of his large wall map to differentiate the ‘unformed stars’ of the large constellation Canis Major. Columba is also shown on his smaller world map of 1594 and on early Dutch celestial globes. Plancius named the constellation Columba Noachi (“Noah‘s Dove”), referring to the dove that gave Noah the information that the Great Flood was receding. This name is found on early 17th-century celestial globes and star atlases.

- Ridpath & Tirion 2001, pp. 120–121.

- Ley, Willy (December 1963). “The Names of the Constellations”. For Your Information. Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 90–99.

1592: Frederick de Houtman listed Columba as “De Duyve med den Olijftack” (“the dove with the olive branch”)

1603: Bayer’s Uranometria was published. It includes Columba as Columba Noachi.

- Canis Maior and Columba in Bayers Uranometria 1603 (Linda Hall Library) Archived 2007-04-27 at the Wayback Machine

1624: Bartschius listed Columba in his Usus Astronomicus as “Columba Nohae”.

1662: Caesius published Coelum Astronomico-Poeticum, including an inaccurate Latin translation of the above text of Clement of Alexandria: it mistranslated “ναῦς οὐριοδρομοῦσα” as Latin “Navis coelestis cursu in coelum tendens” (“Ship of the sky following a course in the sky”), perhaps misunderstanding “οὐριο-” as “up in the air or sky” by analogy with οὐρανός = “sky”.

1679: Halley mentioned Columba in his work Catalogus Stellarum Australium from his observations on St. Helena.

1679: Augustin Royer published a star atlas that showed Columba as a constellation.

c.1690: Hevelius‘s Prodromus Astronomiae showed Columba but did not list it as a constellation.

1712 (pirated) and 1725 (authorized): Flamsteed‘s work Historia Coelestis Britannica showed Columba but did not list it as a constellation.

1757 or 1763: Lacaille listed Columba as a constellation and catalogued its stars.

1889: Richard H. Allen, misled by Caesius’s mistranslation, wrote that the Columba asterism may have been invented in Roman/Greek times, but with a footnote saying that it may have been another star group.

- Richard H. Allen (1899) Star Names: Their Lore and Meaning, pp. 166–168

I love his stuff so and it is in the public domain so, the thing in its entirety:

Others underneath the hunted Hare,

Brown’s Aratos.

All very dim and nameless roll along.

Columba Noae, Noah’s Dove, now known simply as Columba, is the Colombe de Noé of the French, Colomba of the Italians, and Taube of the Germans, lying south of the Hare, and on the meridian with Orion’s Belt.

Although first formally published by Royer in 1679, and so generally considered one of his constellations, it had appeared seventy-six years before correctly located on Bayer’s plate of Canis Major, and in his text as recentioribus Columba; one of these “more recent” being Petrus Plancius, the Dutch cosmographer and map-maker of the 16th century, and instructor of Pieter Theodor. While these are the first allusions to Columba in modern times, yet the following from Caesius may indicate knowledge of its stars,1 and certainly of the present title, seventeen centuries ago. Translating from the Paedagogus of Saint Clement of Alexandria, he wrote:

Signa sive insignia vestra sint Columba, sive Navis coelestis cursu in coelum tendens sive Lyra Musica, in recordationem Apostoli Piscatoris.

Still it was not recognized by Bartschius twenty-one years after Bayer, nor by Tycho, Hevelius, or Flamsteed; but Halley gave it, in the same year as Royer, with ten stars; and our Gould, two centuries later in Argentina, increased the number to seventeen. It was made up from the southwestern outliers of Canis Major, near to the Ship, — Noah’s Ark, — and so was regarded as the attendant Dove.

Smyth wrote of its modern formation, and of its nomenclature in Arab astronomy:

Royer cut away a portion of Canis Major, and constructed Columba Noachi therewith in 1679. The part thus usurped was called Muliphein, from al‑muhlifein, the two stars sworn by, because they were often mistaken for Soheil, or Canopus, before which they rise: these two stars are now α and β Columbae. Muliphein is recognized as comprehending the two stars called Ḥaḍʽár, ground, and al‑wezn, weight.

Reference already has been made to Al Muḥlīfaïn at the stars γ, ζ, and λ Argūs, δ Canis Majoris, and α Centauri.

α, 2.5.

Phaet, Phact, and Phad are all modern names for this, perhaps of uncertain derivation, but said to be from the Ḥaḍar already noted under the constellation. The Chinese call it Chang Jin, the Old Folks. Although inconspicuous, Lockyer thinks that it was of importance in Egyptian temple worship, and observed from Edfū and Philae as far back as 6400 B.C.; but that it was succeeded by Sirius about 3000 B.C., as α Ursae Majoris was by γ Draconis in the north. And he has found three temples at Medinet Habu, adjacent to each other, yet differently oriented, apparently toward α, 2525, 1250, and 900 years before our era: all these to the god Amen. He thinks that as many as twelve different temples were oriented to this star; but the selection of so faint an object for so important a purpose would seem doubtful. Phaet is 33° south of ε Orionis, the central star in the Belt, and culminates on the 26th of January.

β, 2.9.

Wezn, or Wazn, is from Al Wazn, Weight. With α it was among the disputed Al Muḥlīfaïn; and Al Tizini additionally called both stars Al Aghribah, the Ravens, a title that Hyde assigned to a group in Canis Minor. Chilmead’s Treatise has this brief description of Columba: 11 Starres: of which there are two in the backe of it of the second magnitude, which they call the Good messengers, or bringers of good newes: and those in the right wing are consecrated to the Appeased Deity, and those in the left, to the Retiring of the waters in the time of the Deluge. Heis locates α and β in the back: υ2 in the right wing, and ε in the left. θ and κ were included by Kazwini in the Arabic figure Al Kurud, the Apes. In China they were Sun, the Child; λ being Tsze, a Son; and the nearby small stars, She, the Secretions.

The Author’s Note:

1 But the faintness of this constellation is against the probability of such use, and would imply that some other, and more noticeable, sky-group was known as a Dove, possibly Coma Berenices.

- Richard H. Allen (1899) Star Names: Their Lore and Meaning, pp. 166–168

2001: Ridpath and Tirion wrote that Columba may also represent the dove released by Jason and the Argonauts at the Black Sea‘s mouth; it helped them navigate the dangerous Symplegades.

- Ridpath & Tirion 2001, pp. 120–121.

2007: The author P.K. Chen wrote (his opinion) that, given the mythological linkage of a dove with Jason and the Argonauts, and the celestial location of Columba over Puppis (part of the old constellation Argo Navis, the ship of the Argonauts), Columba may have an ancient history although Ptolemy omits it.

- P.K. Chen (2007) A Constellation Album: Stars and Mythology of the Night Sky, p. 126 (ISBN 978-1-931559-38-6).

- Chen, p. 126.

2019–20: OSIRIS-REx students discovered a black hole in the constellation Columba, based on observing X-ray bursts.

- “NASA’s OSIRIS-REx Students Catch Unexpected Glimpse of Newly Discovered Black Hole”. NASA. 28 February 2020

In the Society Islands, Alpha Columbae (Phact) was called Ana-iva.

- Makemson 1941, p. 281.

Features

Stars

See also: List of stars in Columba

Columba is rather inconspicuous, the brightest star, Alpha Columbae, being only of magnitude 2.7. This, a blue-white star, has a pre-Bayer, traditional, Arabic name Phact (meaning ring dove) and is 268 light-years from Earth. The only other named star is Beta Columbae, which has the alike-status name Wazn. It is an orange-hued giant star of magnitude 3.1, 87 light-years away.

- Ridpath & Tirion 2017, p. 122.

The constellation contains the runaway star μ Columbae, which was probably expelled from the ι Orionis system.

Exoplanet NGTS-1b and its star NGTS-1 are in Columba.

General radial velocity

Columba contains the solar antapex – the opposite to the net direction of the solar system (noting the local spiral arm of the Milky Way itself is responsible for most of our change of position over time).[citation needed]

- Madore, Barry F. (14 August 2002). “Astronomical Glossary”. NASA/IPAC Extragalactic Database. Retrieved 31 January 2023.

Deep-sky objects

NGC 1851 a globular cluster in Columba appears at 7th magnitude in a far part of our galaxy as is 39,000 light-years away – it is resolvable south of at greatest latitude +40°N in medium-sized amateur telescopes (under good conditions).

- Ridpath & Tirion 2017, p. 122.

- NGC 1792 is a spiral galaxy of magnitude 10.2.

- NGC 1808 is a Seyfert galaxy of magnitude 10.8.

See also

Citations

- “Columba, constellation boundary”. The Constellations. International Astronomical Union. Archived from the original on 5 June 2013. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- B. Schildgen (2016). Heritage or Heresy: Preservation and Destruction of Religious Art and Architecture in Europe. Springer. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-230-61315-7.

- Ridpath & Tirion 2001, pp. 120–121.

- Ley, Willy (December 1963). “The Names of the Constellations”. For Your Information. Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 90–99.

- Canis Maior and Columba in Bayers Uranometria 1603 (Linda Hall Library) Archived 2007-04-27 at the Wayback Machine

- Richard H. Allen (1899) Star Names: Their Lore and Meaning, pp. 166–168

- P.K. Chen (2007) A Constellation Album: Stars and Mythology of the Night Sky, p. 126 (ISBN 978-1-931559-38-6).

- Chen, p. 126.

- “NASA’s OSIRIS-REx Students Catch Unexpected Glimpse of Newly Discovered Black Hole”. NASA. 28 February 2020.

- Makemson 1941, p. 281.

- Ridpath & Tirion 2017, p. 122.

- Madore, Barry F. (14 August 2002). “Astronomical Glossary”. NASA/IPAC Extragalactic Database. Retrieved 31 January 2023.

References

- Makemson, Maud Worcester (1941). The Morning Star Rises: an account of Polynesian astronomy. Yale University Press. p. 281. Bibcode:1941msra.book…..M.

- Ridpath, Ian; Tirion, Wil (2001), Stars and Planets Guide, Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-08913-2

- Ridpath, Ian; Tirion, Wil (2017). Stars and planets guide (Fifth ed.). London: Collins. ISBN 978-0-00-823927-5. Princeton University Press, Princeton. ISBN 978-0-69-117788-5.

External links

Wikimedia Commons has media related to:

Columba (category)

- The Deep Photographic Guide to the Constellations: Columba

- The clickable Columba

- Star Tales – Columba

- Lost Stars, by Morton Wagman, publ. Mcdonald & Woodward Publishing Company, First printing September 2003, ISBN 0-939923-78-5 , page 110

| Constellation history |

|---|

Leave a Reply