The lactating birds and the bees (gastrin, pepsin, etc)

Crop milk is a secretion from the lining of the crop of parent birds that is regurgitated to young birds. It is found among all pigeons and doves where it is referred to as pigeon milk. An analog to crop milk is also secreted from the esophagus of flamingos and the male emperor penguin.

- Levi, Wendell (1977). The Pigeon. Sumter, S.C.: Levi Publishing Co, Inc. ISBN 0-85390-013-2.

- Silver, Rae (1984). “Prolactin and Parenting in the Pigeon Family” (PDF). The Journal of Experimental Zoology. 232 (3): 617–625. doi:10.1002/jez.1402320330. PMID 6394702. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 September 2016.

- Eraud, C.; Dorie, A.; Jacquet, A.; Faivre, B. (2008). “The crop milk: a potential new route for carotenoid-mediated parental effects” (PDF). Journal of Avian Biology. 39 (2): 247–251. doi:10.1111/j.0908-8857.2008.04053.x.

Description

Crop milk bears little physical resemblance to mammalian milk. Crop milk is a semi-solid substance somewhat like pale yellow cottage cheese. It is extremely high in protein and fat, containing higher levels than cow or human milk.

- Ehrlich, Paul R.; Dobkin, David S.; Wheye, Darryl (1988), “Bird Milk”, stanford.edu

A 1939 study of pigeon crop milk showed, however, that the substance did not contain carbohydrates. It has also been shown to contain anti-oxidants and immune-enhancing factors which contribute to milk immunity. Like mammalian milk, crop milk contains IgA antibodies. It also contains some bacteria. Unlike mammalian milk, which is an emulsion, pigeon crop milk consists of a suspension of protein-rich and fat-rich cells that proliferate and detach from the lining of the crop.

- Davis, W.L. (1939). “The Composition of the Crop Milk of Pigeons”. Biochem. J. 33 (6): 898–901. doi:10.1042/bj0330898. PMC 1264463. PMID 16746989.

- Mysteries of pigeon milk explained, archived from the original on 2011-09-24

- Gillespie, M. J.; Stanley, D.; Chen, H.; Donald, J. A.; Nicholas, K. R.; Moore, R. J.; Crowley, T. M. (2012). Salmon, Henri (ed.). “Functional Similarities between Pigeon ‘Milk’ and Mammalian Milk: Induction of Immune Gene Expression and Modification of the Microbiota”. PLOS ONE. 7 (10): e48363. Bibcode:2012PLoSO…748363G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0048363. PMC 3482181. PMID 23110233.

- Gillespie, M. J.; Haring, V. R.; McColl, K. A.; Monaghan, P.; Donald, J. A.; Nicholas, K. R.; Moore, R. J.; Crowley, T. M. (2011). “Histological and global gene expression analysis of the ‘lactating’ pigeon crop”. BMC Genomics. 12: 452. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-12-452. PMC 3191541. PMID 21929790.

Lactation in birds is controlled by prolactin, which is the same hormone that causes lactation in mammals.

- Gillespie, M. J.; Stanley, D.; Chen, H.; Donald, J. A.; Nicholas, K. R.; Moore, R. J.; Crowley, T. M. (2012). Salmon, Henri (ed.). “Functional Similarities between Pigeon ‘Milk’ and Mammalian Milk: Induction of Immune Gene Expression and Modification of the Microbiota”. PLOS ONE. 7 (10): e48363. Bibcode:2012PLoSO…748363G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0048363. PMC 3482181. PMID 23110233.

Pigeons

Pigeon’s milk begins to be produced a couple of days before the eggs are due to hatch. The parents may cease to eat at this point in order to be able to provide the squabs (baby pigeons and doves) with milk uncontaminated by seeds, which the very young squabs would be unable to digest. The baby squabs are fed on pure crop milk for the first week or so of life. After this the parents begin to introduce a proportion of adult food, softened by spending time in the moist conditions of the adult crop, into the mix fed to the squabs, until by the end of the second week they are being fed entirely on softened adult food.

Pigeons normally lay two eggs. If one egg fails to hatch, the surviving squab gets the advantage of a supply of crop milk sufficient for two squabs and grows at a significantly faster rate. Research suggests that a pair of breeding pigeons cannot produce enough crop milk to feed three squabs adequately, which explains why clutches are limited to two.

- Vandeputte-Poma, J.; van Grembergen, G. (1967). “L’evolution postembryonnaire du poids du pigeon domestique”. Zeitschrift für vergleichende Physiologie (in French). 54 (3): 423–425. doi:10.1007/BF00298228. S2CID 32408737.

- Blockstein, David E. (1989). “Crop milk and clutch size in mourning doves”. The Wilson Bulletin. 101 (1): 11–25. JSTOR 4162684.

The fact that none of the nearly 300 species of Columbiformes has a clutch size larger than two eggs suggests that there is limited plasticity in crop-milk production.

Flamingos

Both the male and the female feed their chicks with a kind of crop milk, produced in glands lining the whole of the upper digestive tract (not just the crop). The hormone prolactin stimulates production. The milk contains fat, protein, and red and white blood cells. (Pigeons and doves—Columbidae—also produce crop milk (just in the glands lining the crop), which contains less fat and more protein than flamingo crop milk.) This crop milk comes out blood red, and it looks precisely like one of the flamingos has been cut open and is feeding its blood to its chick. Flamingo crop milk is dyed red because of a pigment stored in the bird’s liver (canthaxanthin?), a stark contrast from the opaque white coloring of milk from mammals. Flamingo crop milk is so densely packed with carotenoids that when breeding season is over both male and female parents often appear white, losing the pink colouration from their feathers.

- Ehrlich, Paul; Dobkin, David S.; Wheye, Darryl (1988). The Birder’s Handbook. New York, NY, US: Simon & Schuster, Inc. p. 271. ISBN 978-0-671-62133-9.

- The Popular Flamingo website https://thepopularflamingo.com/blogs/posts/how-do-flamingos-feed-their-young

- Sawal, Ibrahim. Why Are Flamingos Pink? NewScientist website https://www.newscientist.com/question/why-are-flamingos-pink

Emperor Penguin

After laying, the mother’s food reserves are exhausted and she very carefully transfers the egg to the male, and then immediately returns to the sea for two months to feed. The chick usually hatches before the mother’s return, and the father feeds it a curd-like substance composed of 59% protein and 28% lipid, which is produced by a gland in his oesophagus. This ability to produce “crop milk” in birds is only found in pigeons, flamingos and male Emperor penguins. The father is able to produce this crop milk to temporarily sustain the chick for generally 4 to 7 days, until the mother returns from fishing at sea with food to properly feed the chick.

- Williams, Tony D. (1995). The Penguins. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-854667-2., p. 158.

- Prévost J, Vilter V (1963). “Histologie de la sécrétion oesophagienne du Manchot empereur”. Proceedings of the XIII International Ornithological Conference (in French): 1085–94.

- ScienceAlert 19 SEP 2011

Some Notes on Bird Digestion

Bird beaks or bills replace the lips and teeth of mammals and vary in shape, size, length and function according to the type of diet consumed. Seed-crackers such as finches have a short conical beak, while birds of prey such as hawks have a powerful hooked beak for tearing flesh (see link on Bird Beaks). The tongue of birds, just as the beak, is adapted to the type of food the bird consumes. A birds mouth is relatively unimportant in eating and digesting food in comparison with, for example, the mammalian mouth. However, most birds do have salivary glands and the beak and tongue do help birds manipulate food for swallowing. After leaving the mouth, food passes through the esophagus on its way to the stomach (in birds called the proventriculus). Many species of birds have an enlarged area of the esophagus known as a crop. The crop is well developed in most species and serves as a temporary storage location for food.

- Fernbank Science Center, http://www.fernbank.edu/birding/digestion.htm

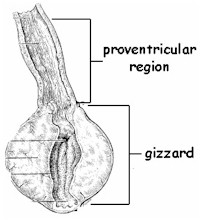

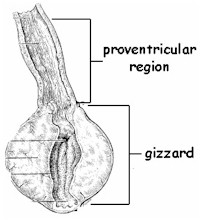

Birds have a two part stomach, a glandular portion known as the proventriculus and a muscular portion known as the gizzard. Hydrochloric acid, mucus and a digestive enzyme, pepsin, are secreted by specialized cells in the proventriculus and starts the process of breaking down the structure of the food material. The food then passes to the second part of the stomach, the gizzard. The gizzard performs the same function as mammalian teeth, grinding and disassembling the food, making it easier for the digestive enzymes to break down the food. In most birds the gizzard contains sand grains or small rocks to aid the grinding process. The crop also allows food to be softened before it enters the stomach. Pigeons and doves produce “crop milk” that they feed to their young for the first two weeks after hatching. Other species, such as ospreys, will regurgitate food that has been stored and softened in their crops and feed it to their young.

- Fernbank Science Center, http://www.fernbank.edu/birding/digestion.htm

Secretions

The secretory glands that line the proventriculus gives it the nickname of the “true stomach,” as it secretes the same components as a mammalian stomach. It contains glands that secrete HCL and pepsinogen. The gastric glands of birds only have one type of cell that produces both HCL and pepsinogen, unlike mammals which have different cell types for each of those productions. In mammals, HCl is secreted into the lumen of the proventriculus using parietal cells, while chief cells secrete the pepsinogen into the lumen.

- Langlois, Isabelle (2003-01-01). “The anatomy, physiology, and diseases of the avian proventriculus and ventriculus”. Veterinary Clinics: Exotic Animal Practice. 6 (1): 85–111. doi:10.1016/S1094-9194(02)00027-0. ISSN 1094-9194. PMID 12616835. Retrieved 2022-11-17.

In birds, the gastric glands of the proventriculus secrete both the HCl and pepsinogen. Since pepsinogen is a zymogen, it is then activated to pepsin, using the HCl. Once activated, pepsin can break the peptide bonds found in peptides and proteins. Since the digesta in birds has not been chewed, the secretions are important to break the particles down.

- Sturkie, Paul D. (1954). Avian physiology. Ithaca, N. Y.: Comstock. Retrieved 2022-11-17.

- Moran, Edwin (2016). “Gastric digestion of protein through pancreozyme action optimizes intestinal forms for absorption, mucin formation and villus integrity”. Animal Feed Science and Technology. 221: 384–303. doi:10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2016.05.015.

Hormones also affect the amount and concentration of these secretions. Some of these include Gastrin, Bombesin, Avian Pancreatic Polypeptide, and cholecystokinin. These can prevent or stimulate the release of those secretions.

- Langlois, Isabelle (2003-01-01). “The anatomy, physiology, and diseases of the avian proventriculus and ventriculus”. Veterinary Clinics: Exotic Animal Practice. 6 (1): 85–111. doi:10.1016/S1094-9194(02)00027-0. ISSN 1094-9194. PMID 12616835. Retrieved 2022-11-17.

The roles of these secretions are to reduce the pH of the digesta and begin protein digestions, however the distribution of the secretions differ depending on the avian species. These secretions cause the stomach to be very acidic, but the exact value will differ based on the species, as seen in the table below.

| Species | pH value |

|---|---|

| Chicken | 4.8 |

| Turkey | 4.7 |

| Pigeon | 4.8 |

| Duck | 3.4 |

Langlois, Isabelle (2003-01-01). “The anatomy, physiology, and diseases of the avian proventriculus and ventriculus”. Veterinary Clinics: Exotic Animal Practice. 6 (1): 85–111. doi:10.1016/S1094-9194(02)00027-0. ISSN 1094-9194. PMID 12616835. Retrieved 2022-11-17.

In petrels, the proventriculus is much larger and the mucus secretions are arranged into longitudinal ridges, which creates more surface area and more concentrated cells.The secretion of the oil is quite common to birds, and are usually undigested fatty acids, but can vary depending on the diet. Petrels also have a unique mechanism where they can shoot stomach oil from their beak when alarmed.

- Imber, M. J. (1976). “The Origin of Petrel Stomach Oils: A Review”. The Condor. 78 (3): 366–369. doi:10.2307/1367697. ISSN 0010-5422. JSTOR 1367697. Retrieved 2022-12-06.

Motility

The muscle contractions of the gizzard push material back into the proventriculus, which then contracts to mix materials between the stomach compartments. This transfer of digested material can occur up to 4 times per minute, and the compartments can hold the stomach contents for thirty minutes to an hour. The contractions are regular and rhythmical, and are more frequent in intact males than in females because there is more concentration of the hormone Androgen. This also causes castrated males to have a decrease in contractions and their amplitude. Smaller and less frequent contractions lead to less effective digestion of food.

- Svihus, Birger (2014). “Function of the Digestive System”. The Journal of Applied Poultry Research. 23 (2): 306–314. doi:10.3382/japr.2014-00937.

- Sturkie, Paul D. (1954). Avian physiology. Ithaca, N. Y.: Comstock. Retrieved 2022-11-17.

Insects

Insects also have a proventriculus structure in their digestive track, although the function and structure differ from avian proventriculi. They still contain secretions, but its main role is to help the passage of food and connect the crop to the stomach. The area within the proventriculus called the proventriculus bulb contains hairs or teeth like structures that help filter food and make it easier to digest. The proventriculus is organized in a central framework with muscles surrounding it on the outside. Different species have different combinations of longitudinal and circular muscles around it. In general, Hymenoptera contain sphincter muscles that add pressure on the digestive components and help pass the food into the midgut. Ants have more longitudinal muscles rather than circular muscles around the proventriculus, and its purpose is to act as a barrier to increase storage capacity of the crop. The amount of time that it can hold food depends on the strength of the muscles around the proventriculus bulb.

- Flavio Henrique Caetano; Xavier Espadaler; Fernando Jose Zara (1998). Comparative Ultramorphology Of The Proventriculus Bulb Of Two Species Of Mutillidae (Hymenoptera). Retrieved 2022-11-17.

- “The evolution and social significance of the ant proventriculus. : Eisner, T. : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive”. Retrieved 2022-11-17.

In bees, it not only controls the movement of food, but also helps separate nectar that will later be converted to honey, from pollen that will be digested. Since the proventriculus controls the passage of food into the digestive track, it is important that it is functional. Male bees are commonly affected by an abnormal proventriculus conditions that prevent the passage of food. In most cases, the proventriculus is swollen and shaped differently. This can later affect how their body absorbs the nutrients since the proventriculus cannot effectively push food into the gut. The exact reason for this abnormality is still unknown, as there are a variety of possibilities. Since it seems to be a sex specific condition, some theories are: changes in the gut biome due to diet or sex-specific pathogens, variability compared to females, or differences in behavior that could affect their exposure to biological threats and toxins.

- Ruiz-Gonzalez, Mario X. (2022). “Abnormal Proventriculus in Bumble Bee Males”. Diversity. 14 (9): 775. doi:10.3390/d14090775.

References

- Levi, Wendell (1977). The Pigeon. Sumter, S.C.: Levi Publishing Co, Inc. ISBN 0-85390-013-2.

- Silver, Rae (1984). “Prolactin and Parenting in the Pigeon Family” (PDF). The Journal of Experimental Zoology. 232 (3): 617–625. doi:10.1002/jez.1402320330. PMID 6394702. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 September 2016.

- Eraud, C.; Dorie, A.; Jacquet, A.; Faivre, B. (2008). “The crop milk: a potential new route for carotenoid-mediated parental effects” (PDF). Journal of Avian Biology. 39 (2): 247–251. doi:10.1111/j.0908-8857.2008.04053.x.

- Ehrlich, Paul R.; Dobkin, David S.; Wheye, Darryl (1988), “Bird Milk”, stanford.edu

- Davis, W.L. (1939). “The Composition of the Crop Milk of Pigeons”. Biochem. J. 33 (6): 898–901. doi:10.1042/bj0330898. PMC 1264463. PMID 16746989.

- Mysteries of pigeon milk explained, archived from the original on 2011-09-24

- Gillespie, M. J.; Stanley, D.; Chen, H.; Donald, J. A.; Nicholas, K. R.; Moore, R. J.; Crowley, T. M. (2012). Salmon, Henri (ed.). “Functional Similarities between Pigeon ‘Milk’ and Mammalian Milk: Induction of Immune Gene Expression and Modification of the Microbiota”. PLOS ONE. 7 (10): e48363. Bibcode:2012PLoSO…748363G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0048363. PMC 3482181. PMID 23110233.

- Gillespie, M. J.; Haring, V. R.; McColl, K. A.; Monaghan, P.; Donald, J. A.; Nicholas, K. R.; Moore, R. J.; Crowley, T. M. (2011). “Histological and global gene expression analysis of the ‘lactating’ pigeon crop”. BMC Genomics. 12: 452. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-12-452. PMC 3191541. PMID 21929790.

- Vandeputte-Poma, J.; van Grembergen, G. (1967). “L’evolution postembryonnaire du poids du pigeon domestique”. Zeitschrift für vergleichende Physiologie (in French). 54 (3): 423–425. doi:10.1007/BF00298228. S2CID 32408737.

- Blockstein, David E. (1989). “Crop milk and clutch size in mourning doves”. The Wilson Bulletin. 101 (1): 11–25. JSTOR 4162684.

The fact that none of the nearly 300 species of Columbiformes has a clutch size larger than two eggs suggests that there is limited plasticity in crop-milk production.

Leave a Reply