Are you ready for a journey into the macabre underbelly of Naples? Welcome to the Catacombs of San Gaudioso, where the dead don’t just rest – they put on a show! Nestled beneath the bustling Rione Sanità district, these 4th-century catacombs are a veritable playground for the morbidly curious. Here’s what awaits you in this underground chamber of horrors:

Walk the same halls where bishops were buried until the 11th century. You’re literally walking on holy ground… and probably some less savory things. Explore frescoes that have survived mudslides, plagues, and centuries of decay. See if you can spot the 5th-century depiction of the Madonna – rumored to be the oldest in all of Campania! Meet San Gaudioso himself! This African bishop fled the Vandals only to become Naples’ star corpse. His tomb is adorned with 6th-century mosaics – talk about posthumous pampering!

Marvel at the “skull-and-fresco” combo platters! In the 17th century, nobles got the VIP treatment: their skulls on display, with custom frescoes of their bodies below. It’s like a medieval Instagram, but way creepier! This art of death was reserved for the wealthy and financially benefited the Dominican Order overseeing the catacombs.

Learn of the crème de la crème of corpse care – the rite of schooling, or as we like to call it, “Corpse Juice Be Gone!” This is Naples’ unique draining method in which bodies were left to drip dry, a gruesome process that gave rise to a nasty Naples curse: “Puozze sculà!” or “May you drain away!” Because nothing says “I hate you” like wishing someone a liquid demise! Meet the schiattamuorto – Naples’ very own “corpse killer.” These brave souls handled the piercing, draining, washing, and arranging of bones. It’s a dirty job, but someone’s gotta do it! FYI, the modern undertaker is still called schiattamuorto.

Picture this: You’re a noble or clergyman, you’ve just kicked the bucket, and you’re thinking, “Gosh, I’d love to stick around for a few centuries, but all these bodily fluids are really cramping my style.” Fear not! Our expert schiattamuorto is here to help! We’ll lovingly place you in our state-of-the-art “cantarelle” – think of it as a spa treatment for the deceased. As you recline in your cozy niche, your less desirable juices will gracefully drain away into our artisanal Greek vases. It’s like a juice cleanse, but for eternity! Once you’re properly drained and dried (we like to call it the “beef jerky” stage), we’ll give your bones a complimentary wash. Because even in death, hygiene matters!

The Catacombs of San Gaudioso: where history comes alive, even if the inhabitants don’t! Remember – in these catacombs, “drain or be drained” isn’t just a saying, it’s a way of death! And who knows, you might just get schooled in the darker side of Naples’ history.

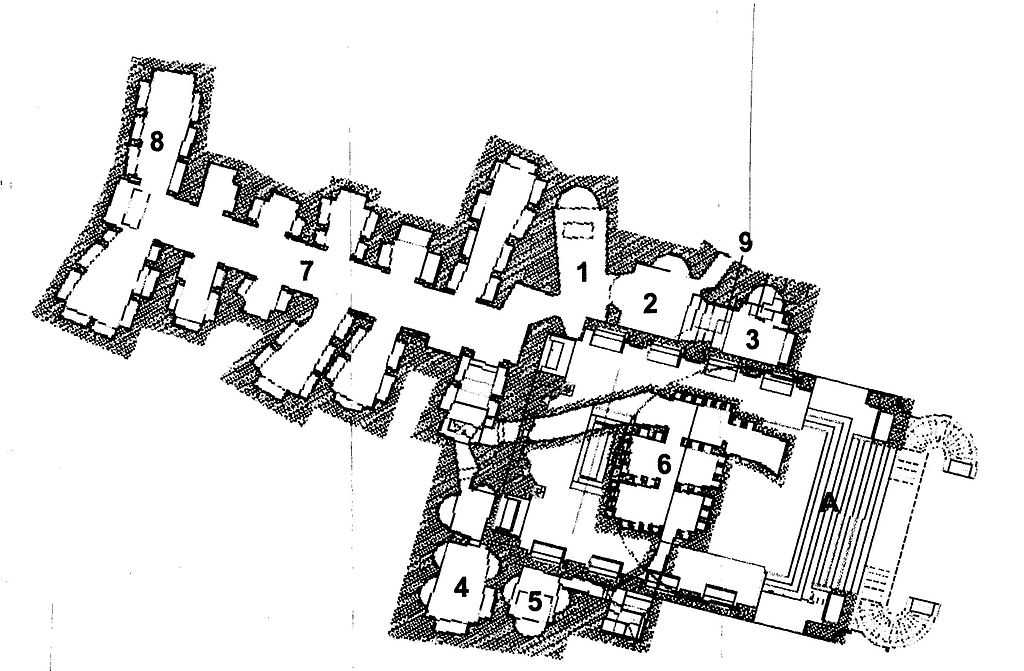

During the seventeenth century, with the construction of the basilica of Santa Maria della Sanità just above the ancient church or chapel of St Gaudioso, the underground cemetery was “modernized” with profound changes in its original structure and resulting in the destruction of some of it.

More Notes

The Catacombs of San Gaudioso offer a captivating journey through Naples’ rich history, blending ancient traditions with macabre practices.

Origins and Early History

Originally a Greek-Roman necropolis, the catacombs became a Christian burial site in the 4th-5th centuries. The site contains valuable 5th and 6th-century frescoes and mosaics featuring early Christian symbols like fish, lamb, and grapes.

Unique Burial Practices

In the 17th century, the catacombs were repurposed for a macabre burial practice for Neapolitan elites:

Corpses were placed in wall niches and strategically pierced.

Bodily fluids drained over a year.

The preserved remains were displayed along the catacomb walls.

Bodies were plastered over, with only the head protruding.

A fresco depicting the deceased as a skeleton was painted connecting to the exposed head.

This process was highly desired by wealthy 17th-century Neapolitans and financially benefited the Dominican Order overseeing the catacombs.

Cultural Significance

Home to Campania’s oldest known depiction of the Virgin Mary, the 5th-6th century Madonna della Sanità fresco.

The catacombs reflect Naples’ complex history, from ancient Roman noble burials to early Christian worship and later aristocratic entombments.

The Catacombs of San Gaudioso stand as a testament to Naples’ layered past, offering a fascinating glimpse into the city’s evolving relationship with death, faith, and social status across the centuries from ancient Roman noble burials to early Christian worship and later aristocratic entombments.

References

https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/catacombs-of-saint-gaudiosus

https://catacombedinapoli.it/en/luoghi/catacombs-of-san-gennaro-naples/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Catacombs_of_Saint_Gaudiosus

https://www.gpsmycity.com/attractions/san-gaudioso-catacombs-25740.html

https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20170223-is-this-the-worlds-most-macabre-art-gallery

https://catacombedinapoli.it/en/luoghi/catacombs-of-san-gaudioso-naples/

Leave a Reply