In ancient Roman religion, the Manes or Di Manes are chthonic deities sometimes thought to represent souls of deceased loved ones. They were associated with the Lares, Lemures, Genii, and Di Penates as deities (di) that pertained to domestic, local, and personal cult. They belonged broadly to the category of di inferi, “those who dwell below,” the undifferentiated collective of divine dead. The Manes were honored during the Parentalia and Feralia in February.

- Varro (1938), “6.13”, De Lingua Latina, London: W. Heinemann, p. 185–7, translated by Kent, Roland G.

- Gagarin, Michael, ed. (2010), “Death”, The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome, vol. 2, Oxford University Press, p. 366, ISBN 9780195170726.

The theologian St. Augustine, writing about the subject a few centuries after most of the Latin pagan references to such spirits, differentiated Manes from other types of Roman spirits:

Apuleius “says, indeed, that the souls of men are demons, and that men become Lares if they are good, Lemures or Larvae if they are bad, and Manes if it is uncertain whether they deserve well or ill… He also states that the blessed are called in Greek εὐδαίμονες [eudaimones], because they are good souls, that is to say, good demons, confirming his opinion that the souls of men are demons.”

— City of God, Book IX, Chapter 11 St. Augustine of Hippo (1871), City of God, vol. 1, Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, p. 365, retrieved 2016-09-15, translated by the Rev. Marcus Dods, M.A.

Latin spells of antiquity were often addressed to the Manes.

- Gager, John G. (1992), Curse Tablets and Binding Spells from the Ancient World, Oxford University Press US, pp. 12–13, ISBN 978-0-19-513482-7, retrieved 2010-08-22.

Etymology and inscriptions

Manes may be derived from “an archaic adjective manus—good—which was the opposite of immanis (monstrous)”.

- Aldington, Richard; Ames, Delano (1968), New Larousse Encyclopedia of Mythology, Yugoslavia: Hamlyn Publishing Group Ltd, p. 213.

Roman tombstones often included the letters D.M., which stood for Dis Manibus, literally “to the Manes”, or figuratively, “to the spirits of the dead”, an abbreviation that continued to appear even in Christian inscriptions.

- King 2020, pp. 2–3.

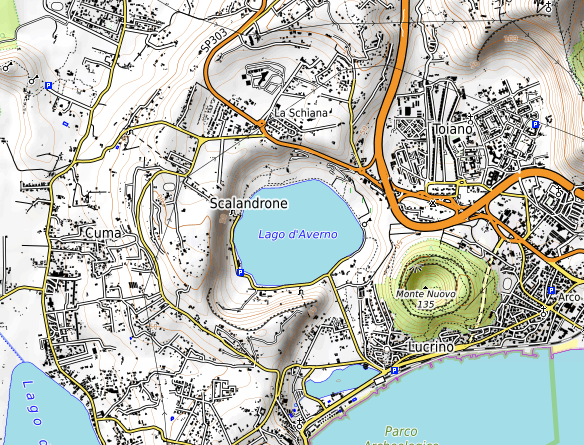

The Manes were offered blood sacrifices. The gladiatorial games, originally held at funerals, may have been instituted in the honor of the Manes. According to Cicero, the Manes could be called forth from the caves near Lake Avernus.

- Aldington, Richard; Ames, Delano (1968), New Larousse Encyclopedia of Mythology, Yugoslavia: Hamlyn Publishing Group Ltd, p. 213.

Lake Avernus is a volcanic crater lake located in the Avernus crater in the Campania region of southern Italy, around 4 kilometres (2+1⁄2 miles) west of Pozzuoli. In the pre-modern era, Italian geographers also called Lago Averno the Lago di Tripergola. It was named after the nearby village of Tripergola, which was destroyed by a volcanic eruption in 1538. It is near the volcanic field known as the Phlegraean Fields (Campi Flegrei) and comprises part of the wider Campanian volcanic arc. Avernus was of major importance to the Romans, who considered it to be the entrance to Hades. Roman writers often used the name as a synonym for the underworld. In Virgil‘s Aeneid, Aeneas descends to the underworld through a cave near the lake. In Hyginus‘ Fabulae, Odysseus also goes to the lower world from this spot, where he meets Elpenor, his comrade who went missing at Circe‘s place. Despite the alleged dangers of the lake, the Romans were happy to settle its shores, on which villas and vineyards were established. The lake’s personification, the deus Avernus, was worshipped in lakeside temples. A large bathhouse was built on the eastern shore of the lake. In 37 BCE, the Roman general Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa converted the lake into a naval base named the Portus Julius after Octavian. It was linked by a canal to a nearby lake (Lucrinus Lacus) and, from there, to the sea. The lake shore was also connected to the Greek colony of Cumae by an underground passage known as Cocceio’s Cave (Grotta di Cocceio), which was one kilometre (five furlongs) long and wide enough to be used by chariots. This was the world’s first major road tunnel; it remained usable until as recently as the 1940s. The Borboni, the Naples-ruling members of the House of Bourbon, owned the lake until 1750 when they ceded it to another aristocratic family, who in turn sold it, in 1991, to the Cardillo family. In 2010, a 55-hectare tract of land—including the lake, a lakefront restaurant, B&B and disco—was seized by the police after the owner was accused of being a mafia frontman (for the Casalesi).

- hyginus, fabulae 125

- The Guardian (11 July 2010). “Italian police seize land around Lake Avernus on suspicion of mafia links”

- Dictionnaire mythologique universel (in French). F. Didot frères. 1846. p. 62.

Le lac est encore connu aujourd’hui sous le nom de lago d’Averno ou lago di Tripergola.

[=”The lake is still known today under the name of lago d’Averno or lago di Tripergola.”] - Brewster, David (1830). The Edinburgh Encyclopædia. Vol. 3. p. 97.

[The lake Avernus] is situated near Puzzuoli in the province of Terra di Lavoro, and is called by the modern Italians Lago d’Averno and Lago di Tripergola.

- Ricciolio, Giovanni Baptista (1661). Geographiæ et Hydrographiæ Reformatæ Libri duodecim (in Latin). ex typographia Haeredis Victorii Benatii. p. 608.

Lago di Tripergola. Avernus lacus. Campaniæ.

- The Quarterly journal of science, literature and art. 1822. p. 424.

Account of the Rise of Monte Nuovo, in the Year 1538 […] the earth opened near Tripergola with a terrible sound like thunder

Lapis manalis

Main article: Lapis manalis

When a new town was founded, a round hole would be dug and a stone called a lapis manalis would be placed in the foundations, representing a gate to the underworld. Due to similar names, the lapis manalis is often confused with the lapis manilis in commentaries even in antiquity: “The ‘flowing stone’ … must not be confused with the stone of the same name which, according to Festus, was the gateway to the underworld.”

- Aldington, Richard; Ames, Delano (1968), New Larousse Encyclopedia of Mythology, Yugoslavia: Hamlyn Publishing Group Ltd, p. 213.

- Burriss, Eli Edward (1931), Taboo, Magic, Spirits: A Study of Primitive Elements in Roman Religion, New York City: Macmillan Company, p. 365, retrieved 2007-08-21.

Cyril Bailey writes:

“Of this we have a characteristic example in the ceremony of the aquaelicium, designed to produce rain after a long drought. In classical times the ceremony consisted in a procession headed by the pontifices, which bore the sacred rain-stone from its resting-place by the Porta Capena to the Capitol, where offerings were made to the sky-deity, Iuppiter, but from the analogy of other primitive cults and the sacred title of the stone (lapis manalis), it is practically certain that the original ritual was the purely imitative process of pouring water over the stone.

Bailey, Cyril (1907), The Religion of Ancient Rome, London: Archibald Constable & Co. Ltd., p. 5, retrieved 2007-08-21.

See also

References

- Varro (1938), “6.13”, De Lingua Latina, London: W. Heinemann, p. 185–7, translated by Kent, Roland G.

- Gagarin, Michael, ed. (2010), “Death”, The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome, vol. 2, Oxford University Press, p. 366, ISBN 9780195170726.

- St. Augustine of Hippo (1871), City of God, vol. 1, Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, p. 365, retrieved 2016-09-15, translated by the Rev. Marcus Dods, M.A.

- Gager, John G. (1992), Curse Tablets and Binding Spells from the Ancient World, Oxford University Press US, pp. 12–13, ISBN 978-0-19-513482-7, retrieved 2010-08-22.

- Aldington, Richard; Ames, Delano (1968), New Larousse Encyclopedia of Mythology, Yugoslavia: Hamlyn Publishing Group Ltd, p. 213.

- King 2020, pp. 2–3.

- Burriss, Eli Edward (1931), Taboo, Magic, Spirits: A Study of Primitive Elements in Roman Religion, New York City: Macmillan Company, p. 365, retrieved 2007-08-21.

- Bailey, Cyril (1907), The Religion of Ancient Rome, London: Archibald Constable & Co. Ltd., p. 5, retrieved 2007-08-21.

- hyginus, fabulae 125

- The Guardian (11 July 2010). “Italian police seize land around Lake Avernus on suspicion of mafia links”

- Dictionnaire mythologique universel (in French). F. Didot frères. 1846. p. 62.

Le lac est encore connu aujourd’hui sous le nom de lago d’Averno ou lago di Tripergola.

[=”The lake is still known today under the name of lago d’Averno or lago di Tripergola.”] - Brewster, David (1830). The Edinburgh Encyclopædia. Vol. 3. p. 97.

[The lake Avernus] is situated near Puzzuoli in the province of Terra di Lavoro, and is called by the modern Italians Lago d’Averno and Lago di Tripergola.

- Ricciolio, Giovanni Baptista (1661). Geographiæ et Hydrographiæ Reformatæ Libri duodecim (in Latin). ex typographia Haeredis Victorii Benatii. p. 608.

Lago di Tripergola. Avernus lacus. Campaniæ.

- The Quarterly journal of science, literature and art. 1822. p. 424.

Account of the Rise of Monte Nuovo, in the Year 1538 […] the earth opened near Tripergola with a terrible sound like thunder

Further reading

- King, Charles W. (2020). The Ancient Roman Afterlife: Di Manes, Belief, and the Cult of the Dead. Austin: University of Texas Press. doi:10.7560/320204. ISBN 978-1-4773-2020-4.

- Chambers, Ephraim, ed. (1728). “Averni”. Cyclopædia, or an Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences (1st ed.). James and John Knapton, et al.

- Undead

- Roman underworld

- Ghosts

- Volcanoes of Italy

- Campanian volcanic arc

- Volcanic crater lakes

- Lakes of Campania

- Pozzuoli

- Archaeological sites in Campania

- Phlegraean Fields

Leave a Reply