The Goldfinch in art

The Goldfinch is unusual for the Dutch Golden Age painting period in the simplicity of its composition and use of illusionary techniques. Following the death of its creator, it was lost for more than two centuries before its rediscovery in Brussels.

The goldfinch is a widespread and common seed-eating bird in Europe, North Africa, and western and central Asia. As a colourful species with a pleasant twittering song, and an associated belief that it brought health and good fortune, it had been domesticated for at least 2,000 years. Pliny recorded that it could be taught to do tricks, and in the 17th century, it became fashionable to train goldfinches to draw water from a bowl with a miniature bucket on a chain.

- Liedtke, Walter A; Plomp, Michiel C; Rüger, Axel (2001). Vermeer and the Delft School. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 260–263. ISBN 978-0-300-08848-9.

- Snow, David; Perrins, Christopher M, eds. (1998). The Birds of the Western Palearctic concise edition (2 volumes). Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 1561–1564. ISBN 978-0-19-854099-1.

- Cocker, Mark; Mabey, Richard (2005). Birds Britannica. London: Chatto & Windus. pp. 448–451. ISBN 978-0-7011-6907-7.

- Lederer, Roger J (2019). The Art of the Bird: The History of Ornithological Art Through Forty Artists. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 15, 21. ISBN 978-0-226-67505-3.

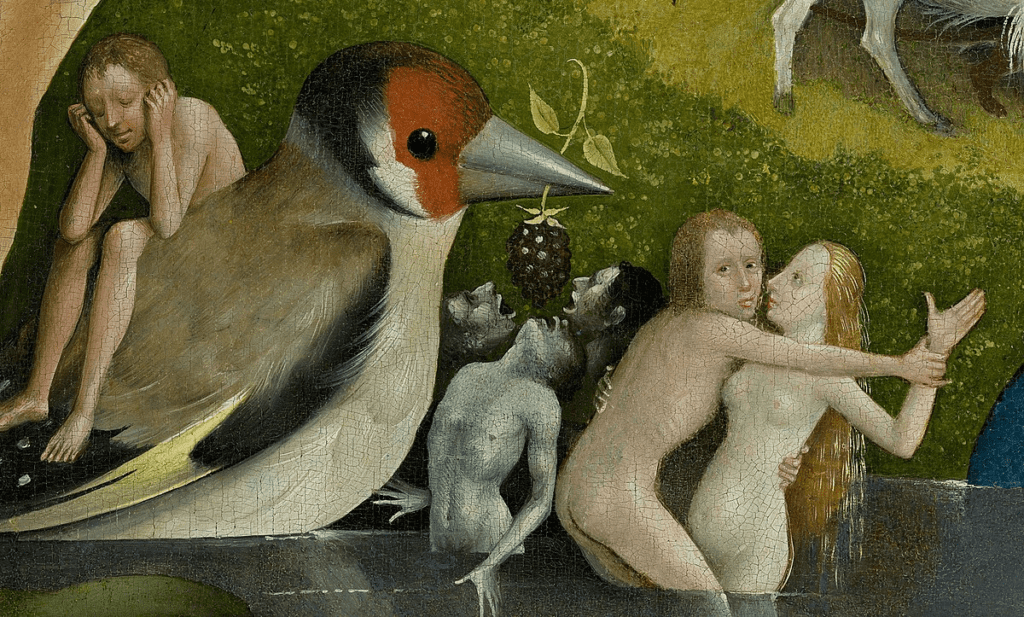

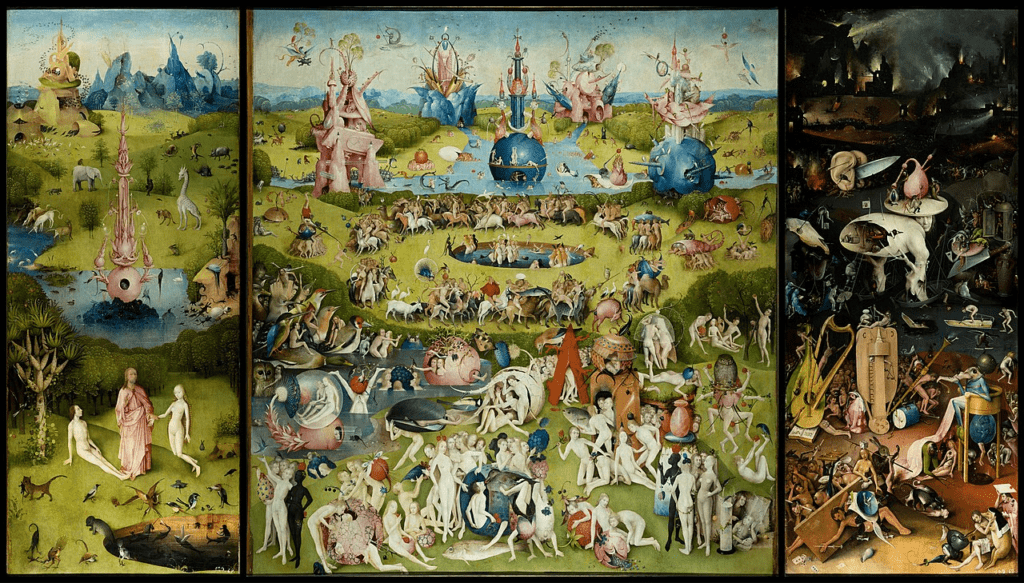

The goldfinch frequently appears in paintings, not just for its colourful appearance but also for its symbolic meanings. Pliny associated the bird with fertility, and the presence of a giant goldfinch next to a naked couple in The Garden of Earthly Delights triptych by the earlier Dutch master Hieronymus Bosch perhaps refers to this belief.

- Cocker, Mark; Mabey, Richard (2005). Birds Britannica. London: Chatto & Windus. pp. 448–451. ISBN 978-0-7011-6907-7.

Nearly 500 Renaissance religious paintings, mainly by Italian artists, show the bird.

- Friedmann, Herbert (1946). Symbolic Goldfinch: Its History and Significance in European Devotional Art. New York: Pantheon. pp. 6, 66. OCLC 294483.

- Friedmann listed 486 paintings by 254 artists of whom 214 were Italian. including da Vinci’sMadonna Litta (1490–1491), Raphael’sMadonna of the Goldfinch (1506) and Piero della Francesca’sNativity (1470).

- “The Goldfinch in Renaissance Art”. BirdLife International. 2008. Archived from the original on 6 April 2020. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

In Medieval Christianity, the goldfinch’s association with health symbolises the Redemption, and its habit of feeding on the seeds of spiky thistles, together with its red face, presaged the crucifixion of Jesus, where the bird supposedly became splattered with blood while attempting to remove the crown of thorns.

- Lederer, Roger J (2019). The Art of the Bird: The History of Ornithological Art Through Forty Artists. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 15, 21. ISBN 978-0-226-67505-3

- Cocker, Mark (2013). Birds and People. London: Jonathan Cape. pp. 500–502. ISBN 978-0-224-08174-0.

Many of these devotional paintings were created in the middle of the fourteenth century while the Black Death pandemic gripped Europe.

- Friedmann, Herbert (1946). Symbolic Goldfinch: Its History and Significance in European Devotional Art. New York: Pantheon. pp. 6, 66. OCLC 294483.

The symbolism persisted long after the time of Fabritius. A much later example of the goldfinch as a symbol of redemption is Hogarth’s 1742 painting The Graham Children.

References

- Liedtke, Walter A; Plomp, Michiel C; Rüger, Axel (2001). Vermeer and the Delft School. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 260–263. ISBN 978-0-300-08848-9.

- Snow, David; Perrins, Christopher M, eds. (1998). The Birds of the Western Palearctic concise edition (2 volumes). Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 1561–1564. ISBN 978-0-19-854099-1.

- Cocker, Mark; Mabey, Richard (2005). Birds Britannica. London: Chatto & Windus. pp. 448–451. ISBN 978-0-7011-6907-7.

- Lederer, Roger J (2019). The Art of the Bird: The History of Ornithological Art Through Forty Artists. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 15, 21. ISBN 978-0-226-67505-3

- Friedmann, Herbert (1946). Symbolic Goldfinch: Its History and Significance in European Devotional Art. New York: Pantheon. pp. 6, 66. OCLC 294483.

- “The Goldfinch in Renaissance Art”. BirdLife International. 2008. Archived from the original on 6 April 2020. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- Cocker, Mark (2013). Birds and People. London: Jonathan Cape. pp. 500–502. ISBN 978-0-224-08174-0.

- “Carel Fabritius, The Goldfinch, 1654”. Mauritshuis. Archived from the original on 5 April 2020. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

- “The Graham Children”. In-depth description. The National Gallery. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- The Graham Children. The National Gallery. Retrieved 7 December 2014.

- The Tate Gallery: An Illustrated Companion to the National Collections of British & Modern Foreign Art. London: Tate Gallery, 1979, p. 15. ISBN 0905005473

- Bindman, David. “Hogarth, William (1697–1764)” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004, online edition, May 2009. Retrieved 7 December 2014. (subscription required)

- Glossary: Conversation Piece. The National Gallery. Retrieved 7 December 2014.

- Postle, Martin. (2005) “The Age of Innocence: Child Portraiture in Georgian Art and Society”, in Pictures of Innocence: Portraits of Children from Hogarth to Lawrence. Bath: Holburne Museum of Art, p. 73. ISBN 0903679094

- Einberg, Elizabeth. (1997) Hogarth the Painter. London: Tate Gallery Publishing, p. 19 & 39. ISBN 1854372343

- Gaunt, William. (1964) A Concise History of English Painting. London: Thames and Hudson, p. 58.

- Bindman, David. (1981) Hogarth. London: Thames & Hudson, p. 144. ISBN 050020182X

- Einberg, Elizabeth. (1987) Manners & Morals: Hogarth and British Painting 1700–1760. London: Tate Gallery, p. 141. ISBN 0946590842

- Lindsey, Jack. (1977) Hogarth: His Art and his World. London: Hart-Davis, MacGibbon, p. 118. ISBN 0246108371

- Becker, Udo. (2000). The Continuum Encyclopedia of Symbols. New York: Continuum. pp. 52–53. ISBN 978-0-8264-1221-8.

- “The Graham Children”. In-depth description. The National Gallery. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

External links

Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Goldfinch.

Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Garden of Earthly Delights.

Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Graham Children.

- National Gallery notes about The Graham Children for primary school teachers.

- Pictures of Innocence: Children in 18th Century Portraiture Abbot Hall Art Gallery, Kendal. Sue Hubbard.

- ‘The Graham Children’ and Painting Related to Childhood. Diana Francocci.

- The Graham family of Harrow.

- The Goldfinch at the Mauritshuis website, including an audio description in English and an animation (captioned in Dutch) for the Edinburgh exhibition.

- At the Museo Nacional del Prado

- “Bosch painted Garden of Earthly Delights for Brussels Palace” Audiovisual by Tvbrussel, 2016

- “The Garden of Earthly Delights: A diachronic interpretation of Hieronymus Bosch’s masterpiece” A lecture by Matthias Riedl

- Audiovisual tour of The Garden of Earthly Delights narrated by Redmond O’Hanlon

- Discussion by Janina Ramirez and Waldemar Januszczak: Art Detective Podcast, 25 Jan 2017

- Panorama of the painting

Leave a Reply