Catecholamine (CA)

A catecholamine (abbreviated CA) is a monoamine neurotransmitter, an organic compound that has a catechol (benzene with two hydroxyl side groups next to each other) and a side-chain amine.

Fitzgerald, P. A. (2011). “Chapter 11. Adrenal Medulla and Paraganglia”. In Gardner, D. G.; Shoback, D. (eds.). Greenspan’s Basic & Clinical Endocrinology (9th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. Retrieved October 26, 2011.

Catechol, not to be confused with Catechin which is also sometimes called catechol, can be either a free molecule or a substituent of a larger molecule, where it represents a 1,2-dihydroxybenzene group. Catechol, also known as pyrocatechol or 1,2-dihydroxybenzene, is a toxic organic compound with the molecular formula C6H4(OH)2. It is the ortho isomer of the three isomeric benzenediols. This colorless compound occurs naturally in trace amounts. It was first discovered by destructive distillation of the plant extract catechin. About 20,000 tonnes of catechol are now synthetically produced annually as a commodity organic chemical, mainly as a precursor to pesticides, flavors, and fragrances. Catechol occurs as feathery white crystals that are very rapidly soluble in water. Small amounts of catechol occur naturally in fruits and vegetables, along with the enzyme polyphenol oxidase (also known as catecholase, or catechol oxidase). Upon mixing the enzyme with the substrate and exposure to oxygen (as when a potato or apple is cut and left out), the colorless catechol oxidizes to reddish-brown melanoid pigments, derivatives of benzoquinone. The enzyme is inactivated by adding an acid, such as citric acid contained in lemon juice. Excluding oxygen also prevents the browning reaction. However, the activity of the enzyme increases in cooler TEMPERATURES. [clarification needed]

Catechol derivatives are found widely in nature. They often arise by hydroxylation of phenols. Arthropod cuticle consists of chitin linked by a catechol moiety to protein. The cuticle may be strengthened by Cross-linking (tanning and sclerotization), in particular, in insects, and of course by biomineralization.

Approximately 50% of the synthetic catechol is consumed in the production of pesticides, the remainder being used as a precursor to fine chemicals such as perfumes and pharmaceuticals. It is a common building block in organic synthesis.

Several industrially significant flavors and fragrances are prepared starting from catechol. Guaiacol is prepared by methylation of catechol and is then converted to vanillin on a scale of about 10M kg per year (1990). The related monoethyl ether of catechol, guethol, is converted to ethylvanillin, a component of chocolate confectioneries.

3-trans-Isocamphylcyclohexanol, widely used as a replacement for sandalwood oil, is prepared from catechol via guaiacol and camphor. Piperonal, a flowery scent, is prepared from the methylene diether of catechol followed by condensation with glyoxal and decarboxylation.

Catechol is used as a black-and-white photographic developer, but, except for some special purpose applications, its use is largely historical. It is rumored to have been used briefly in Eastman Kodak‘s HC-110 developer and is rumored to be a component in Tetenal‘s Neofin Blau developer. It is a key component of Finol from Moersch Photochemie in Germany. Modern catechol developing was pioneered by noted photographer Sandy King. His “PyroCat” formulation is popular among modern black-and-white film photographers. King’s work has since inspired further 21st-century development by others such as Jay De Fehr with Hypercat and Obsidian Acqua developers, and others.

Bolton, Judy L.; Dunlap, Tareisha L.; Dietz, Birgit M. (2018). “Formation and Biological Targets of Botanical o-Quinones”. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 120: 700–707. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2018.07.050. PMC 6643002. PMID 30063944. S2CID 51887182.

Briggs DEG (1999). “Molecular taphonomy of animal and plant cuticles: selective preservation and diagenesis”. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 354 (1379): 7–17. doi:10.1098/rstb.1999.0356. PMC 1692454.

Barner, B. A. (2004) “Catechol” in Encyclopedia of Reagents for Organic Synthesis (Ed: L. Paquette), J. Wiley & Sons, New York. doi:10.1002/047084289X.

Fahlbusch, Karl-Georg et al. (2003) “Flavors and Fragrances” in Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, Wiley-VCH: Weinheim doi:10.1002/14356007.a11_141.

Stephen G. Anchell (2012-09-10). The Darkroom Cookbook. ISBN 978-1136092770.

Stephen G. Anchell; Bill Troop (1998). The Film Developing Cookbook. ISBN 978-0240802770.

Fiegel, Helmut et al. (2002) “Phenol Derivatives” in Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, Wiley-VCH: Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a19_313.

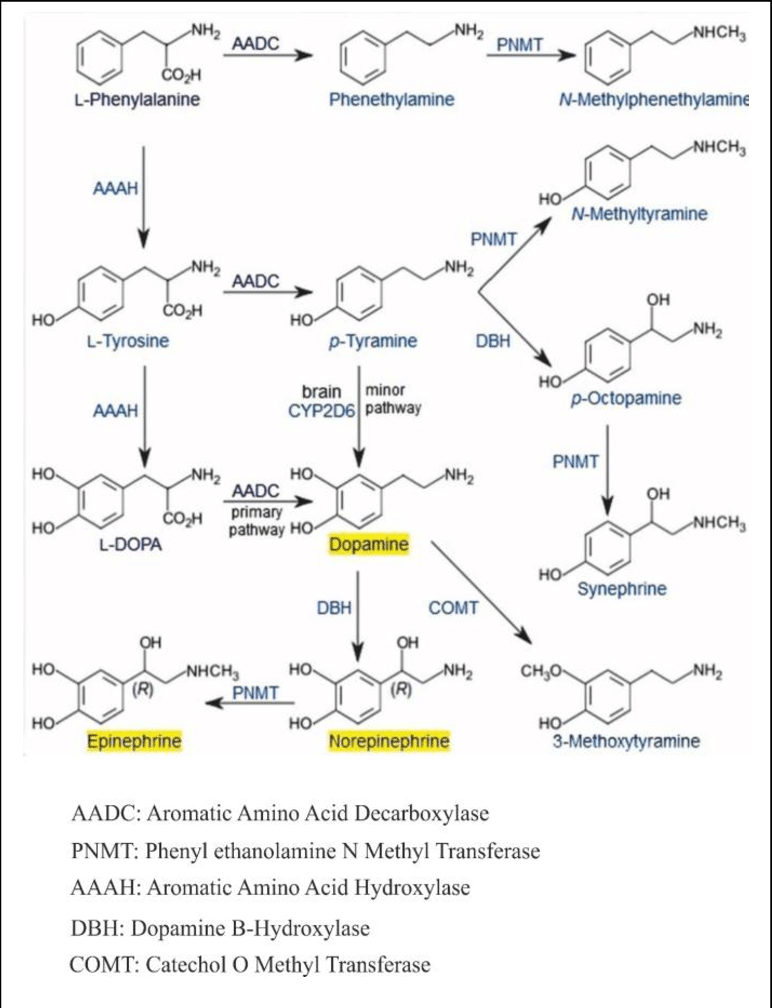

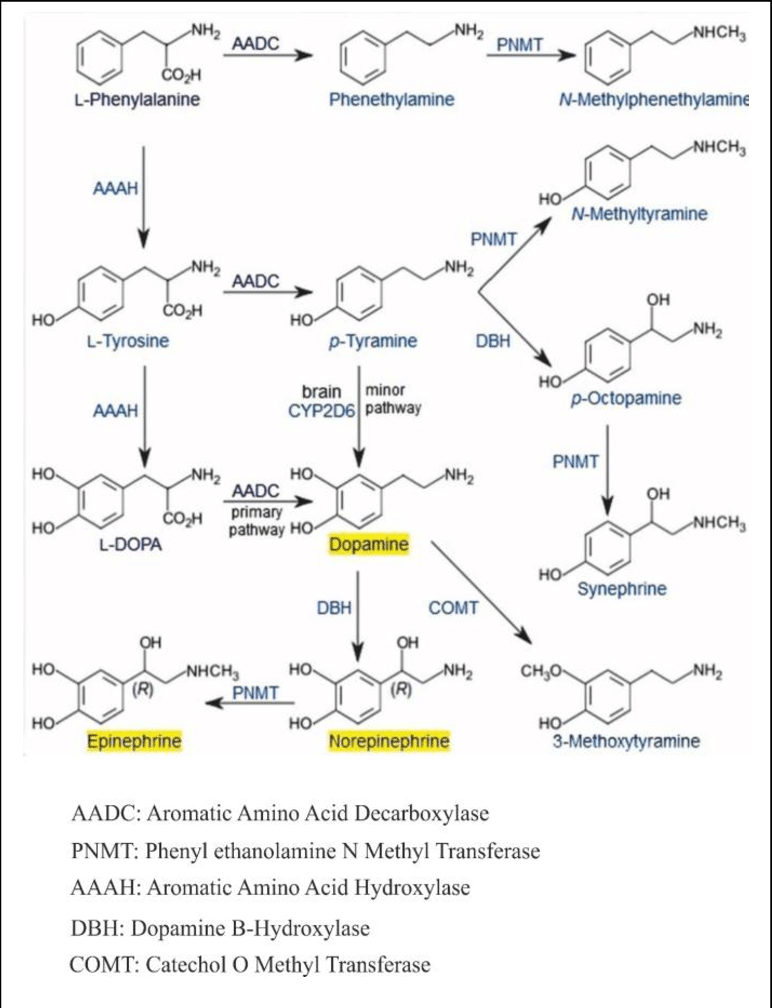

Catecholamines are derived from the amino acid tyrosine, which is derived from dietary sources as well as synthesis from phenylalanine.

Purves, D.; Augustine, G. J.; Fitzpatrick, D.; Hall, W. C.; LaMantia, A. S.; McNamara, J. O.; White, L. E., eds. (2008). Neuroscience (4th ed.). Sinauer Associates. pp. 137–138. ISBN 978-0-87893-697-7

Catecholamines are water-soluble and are 50% bound to plasma proteins in circulation.

Included among catecholamines are epinephrine (adrenaline), norepinephrine (noradrenaline), and dopamine. Release of the hormones epinephrine and norepinephrine from the adrenal medulla of the adrenal glands is part of the fight-or-flight response.

“Catecholamines”. Health Library. San Diego, CA: University of California. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011.

Tyrosine is created from phenylalanine by hydroxylation by the enzyme phenylalanine hydroxylase. Tyrosine is also ingested directly from dietary protein. Catecholamine-secreting cells use several reactions to convert tyrosine serially to L-DOPA and then to dopamine. Depending on the cell type, dopamine may be further converted to norepinephrine or even further converted to epinephrine.

Joh, T. H.; Hwang, O. (1987). “Dopamine Beta-Hydroxylase: Biochemistry and Molecular Biology”. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 493: 342–350. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1987.tb27217.x. PMID 3473965. S2CID 86229251.

Various stimulant drugs (such as a number of substituted amphetamines) are catecholamine analogues.

Structure

Catecholamines have the distinct structure of a benzene ring with two hydroxyl groups, an intermediate ethyl chain, and a terminal amine group. Phenylethanolamines such as norepinephrine have a hydroxyl group on the ethyl chain.[citation needed]

Production and degradation

Location

Catecholamines are produced mainly by the chromaffin cells of the adrenal medulla and the postganglionic fibers of the sympathetic nervous system. Dopamine, which acts as a neurotransmitter in the central nervous system, is largely produced in neuronal cell bodies in two areas of the brainstem: the ventral tegmental area and the substantia nigra, the latter of which contains neuromelanin-pigmented neurons. The similarly neuromelanin-pigmented cell bodies of the locus coeruleus produce norepinephrine. Epinephrine is produced in small groups of neurons in the human brain which express its synthesizing enzyme, phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase; these neurons project from a nucleus that is adjacent (ventrolateral) to the area postrema and from a nucleus in the dorsal region of the solitary tract.

Kitahama, K.; Pearson, J.; Denoroy, L.; Kopp, N.; Ulrich, J.; Maeda, T.; Jouvet, M. (1985). “Adrenergic neurons in human brain demonstrated by immunohistochemistry with antibodies to phenylethanolamine-N-methyltransferase (PNMT): discovery of a new group in the nucleus tractus solitarius”. Neuroscience Letters. 53 (3): 303–308. doi:10.1016/0304-3940(85)90555-5. PMID 3885079. S2CID 2578817.

Biosynthesis

Dopamine is the first catecholamine synthesized from DOPA. In turn, norepinephrine and epinephrine are derived from further metabolic modification of dopamine. The enzyme dopamine hydroxylase requires copper as a cofactor (not shown in the diagram) and DOPA decarboxylase requires PLP (not shown in the diagram). The rate limiting step in catecholamine biosynthesis through the predominant metabolic pathway is the hydroxylation of L-tyrosine to L-DOPA.[citation needed]

Catecholamine synthesis is inhibited by alpha-methyl-p-tyrosine (AMPT), which inhibits tyrosine hydroxylase.[citation needed]

The amino acids phenylalanine and tyrosine are precursors for catecholamines. Both amino acids are found in high concentrations in blood plasma and the brain. In mammals, tyrosine can be formed from dietary phenylalanine by the enzyme phenylalanine hydroxylase, found in large amounts in the liver. Insufficient amounts of phenylalanine hydroxylase result in phenylketonuria, a metabolic disorder that leads to intellectual deficits unless treated by dietary MANIPULATION. [citation needed]

Catecholamine synthesis is usually considered to begin with tyrosine. The enzyme tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) converts the amino acid L-tyrosine into 3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (L-DOPA). The hydroxylation of L-tyrosine by TH results in the formation of the DA precursor L-DOPA, which is metabolized by aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC; see Cooper et al., 2002 [citation needed])

to the transmitter dopamine. This step occurs so rapidly that it is difficult to measure L-DOPA in the brain without first inhibiting AADC. [citation needed]

In neurons that use DA as the transmitter, the decarboxylation of L-DOPA to dopamine is the final step in formation of the transmitter; however, in those neurons using norepinephrine (noradrenaline) or epinephrine (adrenaline) as transmitters, the enzyme dopamine β-hydroxylase (DBH), which converts dopamine to yield norepinephrine, is also present. In still other neurons in which epinephrine is the transmitter, a third enzyme phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase (PNMT) converts norepinephrine into epinephrine. Thus, a cell that uses epinephrine as its transmitter contains four enzymes (TH, AADC, DBH, and PNMT), whereas norepinephrine neurons contain only three enzymes (lacking PNMT) and dopamine cells only two (TH and AADC). [citation needed]

Degradation

Catecholamines have a half-life of a few minutes when circulating in the blood. They can be degraded either by methylation by catechol-O-methyltransferases (COMT) or by deamination by monoamine oxidases (MAO).

MAOIs bind to MAO, thereby preventing it from breaking down catecholamines and other monoamines.

Catabolism of catecholamines is mediated by two main enzymes: catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) which is present in the synaptic cleft and cytosol of the cell and monoamine oxidase (MAO) which is located in the mitochondrial membrane. Both enzymes require cofactors: COMT uses Mg2+ as a cofactor while MAO uses FAD. The first step of the catabolic process is mediated by either MAO or COMT which depends on the tissue and location of catecholamines (for example degradation of catecholamines in the synaptic cleft is mediated by COMT because MAO is a mitochondrial enzyme). The next catabolic steps in the pathway involve alcohol dehydrogenase, aldehyde dehydrogenase and aldehyde reductase. The end product of epinephrine and norepinephrine is vanillylmandelic acid (VMA) which is excreted in the urine. Dopamine catabolism leads to the production of homovanillic acid (HVA).

Eisenhofer, G.; Kopin, I. J.; Goldstein, D. S. (2004). “Catecholamine metabolism: a contemporary view with implications for physiology and medicine”. Pharmacological Reviews. 3 (56): 331–349. doi:10.1124/pr.56.3.1. PMID 15317907. S2CID 12825309.

Function

Modality

Two catecholamines, norepinephrine and dopamine, act as neuromodulators in the central nervous system and as hormones in the blood circulation. The catecholamine norepinephrine is a neuromodulator of the peripheral sympathetic nervous system but is also present in the blood (mostly through “spillover” from the synapses of the sympathetic system). [citation needed]

High catecholamine levels in blood are associated with stress, which can be induced from psychological reactions or environmental stressors such as elevated sound levels, intense light, or low blood sugar levels. [citation needed]

Extremely high levels of catecholamines (also known as catecholamine toxicity) can occur in central nervous system trauma due to stimulation or damage of nuclei in the brainstem, in particular, those nuclei affecting the sympathetic nervous system. In emergency medicine, this occurrence is widely known as a “catecholamine dump”.

Extremely high levels of catecholamine can also be caused by neuroendocrine tumors in the adrenal medulla, a treatable condition known as pheochromocytoma.

High levels of catecholamines can also be caused by monoamine oxidase A (MAO-A) deficiency, known as Brunner syndrome. As MAO-A is one of the enzymes responsible for degradation of these neurotransmitters, its deficiency increases the bioavailability of these neurotransmitters considerably. It occurs in the absence of pheochromocytoma, neuroendocrine tumors, and carcinoid syndrome, but it looks similar to carcinoid syndrome with symptoms such as facial flushing and aggression.

Manor, I.; Tyano, S.; Mel, E.; Eisenberg, J.; Bachner-Melman, R.; Kotler, M.; Ebstein, R. P. (2002). “Family-Based and Association Studies of Monoamine Oxidase A and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): Preferential Transmission of the Long Promoter-Region Repeat and its Association with Impaired Performance on a Continuous Performance Test (TOVA)”. Molecular Psychiatry. 7 (6): 626–632. doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4001037. PMID 12140786.

Brunner, H. G. (1996). “MAOA Deficiency and Abnormal Behaviour: Perspectives on an Association”. Ciba Foundation Symposium. Novartis Foundation Symposia. 194: 155–167. doi:10.1002/9780470514825.ch9. ISBN 9780470514825. PMID 8862875.

Acute porphyria can cause elevated catecholamines.

Stewart, M. F.; Croft, J.; Reed, P.; New, J. P. (2006). “Acute intermittent porphyria and phaeochromocytoma: shared features”. Journal of Clinical Pathology. 60 (8): 935–936. doi:10.1136/jcp.2005.032722. PMC 1994495. PMID 17660335.

Effects

Catecholamines cause general physiological changes that prepare the body for physical activity (the fight-or-flight response). Some typical effects are increases in heart rate, blood pressure, blood glucose levels, and a general reaction of the sympathetic nervous system. [citation needed]

Some drugs, like tolcapone (a central COMT-inhibitor), raise the levels of all the catecholamines. Increased catecholamines may also cause an increased respiratory rate (tachypnoea) in patients.

Kuklin, A. I.; Conger, B. V. (1995). “Catecholamines in Plants”. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation. 14 (2): 91–97. doi:10.1007/BF00203119. S2CID 41493767.

Catecholamine is secreted into urine after being broken down, and its secretion level can be measured for the diagnosis of illnesses associated with catecholamine levels in the body.

“Catecholamines in Urine”. webmd.com. Retrieved 4 May 2017.

Urine testing for catecholamine is used to detect pheochromocytoma. Pheochromocytoma is a rare tumor of the adrenal medulla composed of chromaffin cells, also known as pheochromocytes. When a tumor composed of the same cells as a pheochromocytoma develops outside the adrenal gland, it is referred to as a paraganglioma. These neuroendocrine tumors typically release massive amounts of catecholamines, metanephrines, or methoxytyramine, which result in the most common symptoms, including hypertension (high blood pressure), tachycardia (fast heart rate), and diaphoresis (sweating). Rarely, some tumors (especially paragangliomas) may secrete little to no catecholamines, making diagnosis difficult. While tumors of the head and neck are parasympathetic, their sympathetic counterparts are predominantly located in the abdomen and pelvis, particularly concentrated at the organ of Zuckerkandl. Etymology from phaeochrome (another term for chromaffin), from Greek phaios ‘dusky’ + khrōma ‘color’, + -cyte. 1920s.

Lenders JW, Eisenhofer G, Mannelli M, Pacak K (20–26 August 2005). “Phaeochromocytoma”. Lancet. 366 (9486): 665–75. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67139-5. PMID 16112304. S2CID 208788653.

Oyasu R, Yang XJ, Yoshida O, eds. (2008). “What is the difference between pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma? What are the familial syndromes that have pheochromocytoma as a component? What are the pathologic features of pheochromocytoma indicating malignancy?”. Questions in Daily Urologic Practice. Questions in Daily Urologic Practice: Updates for Urologists and Diagnostic Pathologists. Tokyo: Springer Japan. pp. 280–284. doi:10.1007/978-4-431-72819-1_49. ISBN 978-4-431-72819-1.

Lenders JW, Pacak K, Walther MM, Linehan WM, Mannelli M, Friberg P, et al. (March 2002). “Biochemical diagnosis of pheochromocytoma: which test is best?”. JAMA. 287 (11): 1427–34. doi:10.1001/jama.287.11.1427. PMID 11903030.

“Internal Medicine”. JAMA. 286 (8): 971. 2001-08-22. doi:10.1001/jama.286.8.971-jbk0822-2-1. ISSN 0098-7484.

Kellerman RD, Rakel D (2020). Conn’s Current Therapy. Elsevier–Health Science. ISBN 978-0-323-79006-2. OCLC 1145315791.

Function in plants

They have been found in 44 plant families but no essential metabolic

function has been established for them. They are precursors of benzo[c]phenanthridine alkaloids, which are the active principal

ingredients of many medicinal plant extracts. CAs have been implicated

to have a possible protective role against insect predators, injuries,

and nitrogen detoxification. They have been shown to promote plant

tissue growth, somatic embryogenesis from in vitro cultures, and

flowering. CAs inhibit indole-3-acetic acid oxidation and enhance ethylene biosynthesis. They have also been shown to enhance synergistically various effects of gibberellins.

Kuklin, A. I.; Conger, B. V. (1995). “Catecholamines in Plants”. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation. 14 (2): 91–97. doi:10.1007/BF00203119. S2CID 41493767.

Testing for catecholamines

Catecholamines are secreted by cells in tissues of different systems of the human body, mostly by the nervous and the endocrine systems. The adrenal glands secrete certain catecholamines into the blood when the person is physically or mentally stressed and this is usually a healthy physiological response. [citation needed]

However, acute or chronic excess of circulating catecholamines can potentially increase blood pressure and heart rate to very high levels and eventually provoke dangerous effects. Tests for fractionated plasma free metanephrines or the urine metanephrines are used to confirm or exclude certain diseases when the doctor identifies signs of hypertension and tachycardia that don’t adequately respond to treatment.

“Plasma Free Metanephrines | Lab Tests Online”. labtestsonline.org. Retrieved 2019-12-24.

“Urine Metanephrines | Lab Tests Online”. labtestsonline.org. 6 December 2019. Retrieved 2019-12-24.

Each of the tests measure the amount of adrenaline and noradrenaline metabolites, respectively called metanephrine and normetanephrine.

Blood tests are also done to analyze the amount of catecholamines present in the body.

Catecholamine tests are done to identify rare tumors at the adrenal gland or in the nervous system. Catecholamine tests provide information relative to tumors such as: pheochromocytoma, paraganglioma, and neuroblastoma.

“Catecholamine Urine & Blood Tests”. WebMD. Retrieved 2019-10-09.

“Catecholamines”. labtestsonline.org. Retrieved 2019-10-09.

See also

- Catechol-O-methyl transferase

- Catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia

- History of catecholamine research

- Hormone

- Julius Axelrod

- Peptide hormone

- Phenethylamines

- Steroid hormone

- Sympathomimetics

- Vanillylmandelic acid

References

- Fitzgerald, P. A. (2011). “Chapter 11. Adrenal Medulla and Paraganglia”. In Gardner, D. G.; Shoback, D. (eds.). Greenspan’s Basic & Clinical Endocrinology (9th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. Retrieved October 26, 2011.

- Purves, D.; Augustine, G. J.; Fitzpatrick, D.; Hall, W. C.; LaMantia, A. S.; McNamara, J. O.; White, L. E., eds. (2008). Neuroscience (4th ed.). Sinauer Associates. pp. 137–138. ISBN 978-0-87893-697-7.

- “Catecholamines”. Health Library. San Diego, CA: University of California. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011.

- Joh, T. H.; Hwang, O. (1987). “Dopamine Beta-Hydroxylase: Biochemistry and Molecular Biology”. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 493: 342–350. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1987.tb27217.x. PMID 3473965. S2CID 86229251.

- Broadley KJ (March 2010). “The vascular effects of trace amines and amphetamines”. Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 125 (3): 363–375. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.11.005. PMID 19948186.

- Lindemann L, Hoener MC (May 2005). “A renaissance in trace amines inspired by a novel GPCR family”. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 26 (5): 274–281. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2005.03.007. PMID 15860375.

- Wang X, Li J, Dong G, Yue J (February 2014). “The endogenous substrates of brain CYP2D”. European Journal of Pharmacology. 724: 211–218. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.12.025. PMID 24374199.

- Kitahama, K.; Pearson, J.; Denoroy, L.; Kopp, N.; Ulrich, J.; Maeda, T.; Jouvet, M. (1985). “Adrenergic neurons in human brain demonstrated by immunohistochemistry with antibodies to phenylethanolamine-N-methyltransferase (PNMT): discovery of a new group in the nucleus tractus solitarius”. Neuroscience Letters. 53 (3): 303–308. doi:10.1016/0304-3940(85)90555-5. PMID 3885079. S2CID 2578817.

- Eisenhofer, G.; Kopin, I. J.; Goldstein, D. S. (2004). “Catecholamine metabolism: a contemporary view with implications for physiology and medicine”. Pharmacological Reviews. 3 (56): 331–349. doi:10.1124/pr.56.3.1. PMID 15317907. S2CID 12825309.

- Manor, I.; Tyano, S.; Mel, E.; Eisenberg, J.; Bachner-Melman, R.; Kotler, M.; Ebstein, R. P. (2002). “Family-Based and Association Studies of Monoamine Oxidase A and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): Preferential Transmission of the Long Promoter-Region Repeat and its Association with Impaired Performance on a Continuous Performance Test (TOVA)”. Molecular Psychiatry. 7 (6): 626–632. doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4001037. PMID 12140786.

- Brunner, H. G. (1996). “MAOA Deficiency and Abnormal Behaviour: Perspectives on an Association”. Ciba Foundation Symposium. Novartis Foundation Symposia. 194: 155–167. doi:10.1002/9780470514825.ch9. ISBN 9780470514825. PMID 8862875.

- Stewart, M. F.; Croft, J.; Reed, P.; New, J. P. (2006). “Acute intermittent porphyria and phaeochromocytoma: shared features”. Journal of Clinical Pathology. 60 (8): 935–936. doi:10.1136/jcp.2005.032722. PMC 1994495. PMID 17660335.

- Estes, Mary (2016). Health assessment and physical examination (2nd ed.). Melbourne: Cengage. p. 143. ISBN 9780170354844.

- “Catecholamines in Urine”. webmd.com. Retrieved 4 May 2017.

- Kuklin, A. I.; Conger, B. V. (1995). “Catecholamines in Plants”. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation. 14 (2): 91–97. doi:10.1007/BF00203119. S2CID 41493767.

- “Plasma Free Metanephrines | Lab Tests Online”. labtestsonline.org. Retrieved 2019-12-24.

- “Urine Metanephrines | Lab Tests Online”. labtestsonline.org. 6 December 2019. Retrieved 2019-12-24.

- “Catecholamine Urine & Blood Tests”. WebMD. Retrieved 2019-10-09.

- “Catecholamines”. labtestsonline.org. Retrieved 2019-10-09.

- Lenders JW, Eisenhofer G, Mannelli M, Pacak K (20–26 August 2005). “Phaeochromocytoma”. Lancet. 366 (9486): 665–75. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67139-5. PMID 16112304. S2CID 208788653.

- Oyasu R, Yang XJ, Yoshida O, eds. (2008). “What is the difference between pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma? What are the familial syndromes that have pheochromocytoma as a component? What are the pathologic features of pheochromocytoma indicating malignancy?”. Questions in Daily Urologic Practice. Questions in Daily Urologic Practice: Updates for Urologists and Diagnostic Pathologists. Tokyo: Springer Japan. pp. 280–284. doi:10.1007/978-4-431-72819-1_49. ISBN 978-4-431-72819-1.

- Lenders JW, Pacak K, Walther MM, Linehan WM, Mannelli M, Friberg P, et al. (March 2002). “Biochemical diagnosis of pheochromocytoma: which test is best?”. JAMA. 287 (11): 1427–34. doi:10.1001/jama.287.11.1427. PMID 11903030.

- “Internal Medicine”. JAMA. 286 (8): 971. 2001-08-22. doi:10.1001/jama.286.8.971-jbk0822-2-1. ISSN 0098-7484.

- Kellerman RD, Rakel D (2020). Conn’s Current Therapy. Elsevier–Health Science. ISBN 978-0-323-79006-2. OCLC 1145315791.

- Barner, B. A. (2004) “Catechol” in Encyclopedia of Reagents for Organic Synthesis (Ed: L. Paquette), J. Wiley & Sons, New York. doi:10.1002/047084289X.

- Fahlbusch, Karl-Georg et al. (2003) “Flavors and Fragrances” in Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, Wiley-VCH: Weinheim doi:10.1002/14356007.a11_141.

- Stephen G. Anchell (2012-09-10). The Darkroom Cookbook. ISBN 978-1136092770.

- Stephen G. Anchell; Bill Troop (1998). The Film Developing Cookbook. ISBN 978-0240802770.

- Fiegel, Helmut et al. (2002) “Phenol Derivatives” in Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, Wiley-VCH: Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a19_313.

- Bolton, Judy L.; Dunlap, Tareisha L.; Dietz, Birgit M. (2018). “Formation and Biological Targets of Botanical o-Quinones”. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 120: 700–707. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2018.07.050. PMC 6643002. PMID 30063944. S2CID 51887182.

- Briggs DEG (1999). “Molecular taphonomy of animal and plant cuticles: selective preservation and diagenesis”. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 354 (1379): 7–17. doi:10.1098/rstb.1999.0356. PMC 1692454.

External links

- Catecholamines at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

Leave a Reply