Streptomyces is the largest genus of Actinomycetota, and the type genus of the family Streptomycetaceae. Over 700 species of Streptomyces bacteria have been described.

- Kämpfer P (2006). “The Family Streptomycetaceae, Part I: Taxonomy”. In Dworkin M, Falkow S, Rosenberg E, Schleifer KH, Stackebrandt E (eds.). The Prokaryotes. pp. 538–604. doi:10.1007/0-387-30743-5_22. ISBN 978-0-387-25493-7.

- Euzéby JP (2008). “Genus Streptomyces”. List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature. Retrieved 2008-09-28.

- Nikolaidis, Marios; Hesketh, Andrew; Frangou, Nikoletta; Mossialos, Dimitris; Van de Peer, Yves; Oliver, Stephen G.; Amoutzias, Grigorios D. (June 2023). “A panoramic view of the genomic landscape of the genus Streptomyces”. Microbial Genomics. 9 (6). doi:10.1099/mgen.0.001028. ISSN 2057-5858. PMID 37266990. S2CID 259025020.

- “Genus: Streptomyces”. www.bacterio.net. Retrieved 2023-06-21.

As with the other Actinomycetota, streptomycetes are gram-positive, and have very large genomes with high GC content.

- Nikolaidis, Marios; Hesketh, Andrew; Frangou, Nikoletta; Mossialos, Dimitris; Van de Peer, Yves; Oliver, Stephen G.; Amoutzias, Grigorios D. (June 2023). “A panoramic view of the genomic landscape of the genus Streptomyces”. Microbial Genomics. 9 (6). doi:10.1099/mgen.0.001028. ISSN 2057-5858. PMID 37266990. S2CID 259025020.

- Madigan M, Martinko J, eds. (2005). Brock Biology of Microorganisms (11th ed.). Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-144329-7.[page needed]

Found predominantly in soil and decaying vegetation, most streptomycetes produce spores, and are noted for their distinct “earthy” odor that results from production of a volatile metabolite, geosmin.

- John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, ed. (2001-05-30). eLS (1 ed.). Wiley. doi:10.1002/9780470015902.a0020392.pub2. ISBN 978-0-470-01617-6.

Different strains of the same species may colonize very diverse environments.

- Nikolaidis, Marios; Hesketh, Andrew; Frangou, Nikoletta; Mossialos, Dimitris; Van de Peer, Yves; Oliver, Stephen G.; Amoutzias, Grigorios D. (June 2023). “A panoramic view of the genomic landscape of the genus Streptomyces”. Microbial Genomics. 9 (6). doi:10.1099/mgen.0.001028. ISSN 2057-5858. PMID 37266990. S2CID 259025020.

Streptomycetes are characterised by a complex secondary metabolism. Between 5-23% (average: 12%) of the protein-coding genes of each Streptomyces species are implicated in secondary metabolism.

- Nikolaidis, Marios; Hesketh, Andrew; Frangou, Nikoletta; Mossialos, Dimitris; Van de Peer, Yves; Oliver, Stephen G.; Amoutzias, Grigorios D. (June 2023). “A panoramic view of the genomic landscape of the genus Streptomyces”. Microbial Genomics. 9 (6). doi:10.1099/mgen.0.001028. ISSN 2057-5858. PMID 37266990. S2CID 259025020.

- Madigan M, Martinko J, eds. (2005). Brock Biology of Microorganisms (11th ed.). Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-144329-7.[page needed]

Streptomycetes produce over two-thirds of the clinically useful antibiotics of natural origin (e.g., neomycin, streptomycin, cypemycin, grisemycin, bottromycins and chloramphenicol).

- Kieser T, Bibb MJ, Buttner MJ, Chater KF, Hopwood DA (2000). Practical Streptomyces Genetics (2nd ed.). Norwich, England: John Innes Foundation. ISBN 978-0-7084-0623-6.[page needed]

- Bibb MJ (December 2013). “Understanding and manipulating antibiotic production in actinomycetes”. Biochemical Society Transactions. 41 (6): 1355–64. doi:10.1042/BST20130214. PMID 24256223.

The antibiotic streptomycin takes its name directly from Streptomyces. Streptomycetes are infrequent pathogens, though infections in humans, such as mycetoma, can be caused by S. somaliensis and S. sudanensis, and in plants can be caused by S. caviscabies, S. acidiscabies, S. turgidiscabies and S. scabies.

Taxonomy

See also: List of Streptomyces species

Streptomyces is the type genus of the family Streptomycetaceae and currently covers more than 700 species with the number increasing every year. It is estimated that the total number of Streptomyces species is close to 1600.

- Nikolaidis, Marios; Hesketh, Andrew; Frangou, Nikoletta; Mossialos, Dimitris; Van de Peer, Yves; Oliver, Stephen G.; Amoutzias, Grigorios D. (June 2023). “A panoramic view of the genomic landscape of the genus Streptomyces”. Microbial Genomics. 9 (6). doi:10.1099/mgen.0.001028. ISSN 2057-5858. PMID 37266990. S2CID 259025020.

- Anderson AS, Wellington EM (May 2001). “The taxonomy of Streptomyces and related genera”. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 51 (Pt 3): 797–814. doi:10.1099/00207713-51-3-797. PMID 11411701.

- Labeda DP (October 2011). “Multilocus sequence analysis of phytopathogenic species of the genus Streptomyces”. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 61 (Pt 10): 2525–2531. doi:10.1099/ijs.0.028514-0. PMID 21112986.

- “Genus: Streptomyces”. www.bacterio.net. Retrieved 2023-06-21.

Acidophilic and acid-tolerant strains that were initially classified under this genus have later been moved to Kitasatospora (1997) and Streptacidiphilus (2003). Species nomenclature are usually based on their color of hyphae and spores.

- Zhang Z, Wang Y, Ruan J (October 1997). “A proposal to revive the genus Kitasatospora (Omura, Takahashi, Iwai, and Tanaka 1982)”. International Journal of Systematic Bacteriology. 47 (4): 1048–54. doi:10.1099/00207713-47-4-1048. PMID 9336904.

- Kim SB, Lonsdale J, Seong CN, Goodfellow M (2003). “Streptacidiphilus gen. nov., acidophilic actinomycetes with wall chemotype I and emendation of the family Streptomycetaceae (Waksman and Henrici (1943)AL) emend. Rainey et al. 1997”. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. 83 (2): 107–16. doi:10.1023/A:1023397724023. PMID 12785304. S2CID 12901116.

Saccharopolyspora erythraea was formerly placed in this genus (as Streptomyces erythraeus).

Morphology

The genus Streptomyces includes aerobic, Gram-positive, multicellular, filamentous bacteria that produce well-developed vegetative hyphae (between 0.5-2.0 µm in diameter) with branches. They form a complex substrate mycelium that aids in scavenging organic compounds from their substrates. Although the mycelia and the aerial hyphae that arise from them are amotile, mobility is achieved by dispersion of spores. Spore surfaces may be hairy, rugose, smooth, spiny or warty. In some species, aerial hyphae consist of long, straight filaments, which bear 50 or more spores at more or less regular intervals, arranged in whorls (verticils). Each branch of a verticil produces, at its apex, an umbel, which carries from two to several chains of spherical to ellipsoidal, smooth or rugose spores. Some strains form short chains of spores on substrate hyphae. Sclerotia-, pycnidia-, sporangia-, and synnemata-like structures are produced by some strains.

- Chater K, Losick R (1984). “Morphological and physiological differentiation in Streptomyces“. Microbial development. Vol. 16. pp. 89–115. doi:10.1101/0.89-115 (inactive 31 December 2022). ISBN 978-0-87969-172-1. Retrieved 2012-01-19.

- Dietz A, Mathews J (March 1971). “Classification of Streptomyces spore surfaces into five groups”. Applied Microbiology. 21 (3): 527–33. doi:10.1128/AEM.21.3.527-533.1971. PMC 377216. PMID 4928607.

Genomics

The complete genome of “S. coelicolor strain A3(2)” was published in 2002. At the time, the “S. coelicolor” genome was thought to contain the largest number of genes of any bacterium. The chromosome is 8,667,507 bp long with a GC-content of 72.1%, and is predicted to contain 7,825 protein-encoding genes.

- Bentley SD, Chater KF, Cerdeño-Tárraga AM, Challis GL, Thomson NR, James KD, et al. (May 2002). “Complete genome sequence of the model actinomycete Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2)”. Nature. 417 (6885): 141–7. Bibcode:2002Natur.417..141B. doi:10.1038/417141a. PMID 12000953. S2CID 4430218.

In terms of taxonomy, “S. coelicolor A3(2)” belongs to the species S. violaceoruber, and is not a validly described separate species; “S. coelicolor A3(2)” is not to be mistaken for the actual S. coelicolor (Müller), although it is often referred to as S. coelicolor for convenience. The transcriptome and translatome analyses of the strain A3(2) were published in 2016.

- Chater KF, Biró S, Lee KJ, Palmer T, Schrempf H (March 2010). “The complex extracellular biology of Streptomyces”. FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 34 (2): 171–98. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6976.2009.00206.x. PMID 20088961.

- Jeong Y, Kim JN, Kim MW, Bucca G, Cho S, Yoon YJ, et al. (June 2016). “The dynamic transcriptional and translational landscape of the model antibiotic producer Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2)”. Nature Communications. 7 (1): 11605. Bibcode:2016NatCo…711605J. doi:10.1038/ncomms11605. PMC 4895711. PMID 27251447.

The first complete genome sequence of S. avermitilis was completed in 2003. Each of these genomes forms a chromosome with a linear structure, unlike most bacterial genomes, which exist in the form of circular chromosomes. The genome sequence of S. scabies, a member of the genus with the ability to cause potato scab disease, has been determined at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute. At 10.1 Mbp long and encoding 9,107 provisional genes, it is the largest known Streptomyces genome sequenced, probably due to the large pathogenicity island. Pathogenicity islands (PAIs), as termed in 1990, are a distinct class of genomic islands acquired by microorganisms through horizontal gene transfer (the movement of genetic material between unicellular and/or multicellular organisms other than by the “vertical” transmission of DNA from parent to offspring). Pathogenicity islands are found in both animal and plant pathogens. Additionally, PAIs are found in both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. They are transferred through horizontal gene transfer events such as transfer by a plasmid, phage, or conjugative transposon. Therefore, PAIs contribute to microorganisms’ ability to evolve. One species of bacteria may have more than one PAI. For example, Salmonella has at least five.[citation needed] An analogous genomic structure in rhizobia is termed a symbiosis island.)

- Ikeda H, Ishikawa J, Hanamoto A, Shinose M, Kikuchi H, Shiba T, et al. (May 2003). “Complete genome sequence and comparative analysis of the industrial microorganism Streptomyces avermitilis”. Nature Biotechnology. 21 (5): 526–31. doi:10.1038/nbt820. PMID 12692562.

- Dyson P (1 January 2011). Streptomyces: Molecular Biology and Biotechnology. Horizon Scientific Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-904455-77-6. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- “Streptomyces scabies”. Sanger Institute. Retrieved 2001-02-26.

- Hacker, J; Bender, L; Ott, M; et al. (1990). “Deletions of chro- mosomal regions coding for fimbriae and hemolysins occur in vivo and in vitro in various extraintestinal Escherichia coli iso- lates”. Microb. Pathog. 8 (3): 213–25. doi:10.1016/0882-4010(90)90048-U. PMID 1974320.

- Hacker, J; Kaper, JB (2000). “Pathogenicity islands and the evolution of microbes”. Annu Rev Microbiol. 54: 641–679. doi:10.1146/annurev.micro.54.1.641. PMID 11018140. S2CID 1945976.

- Hacker, J.; Blum-Oehler, G.; Muhldorfer, I.; Tschape, H. (1997). “Pathogenecity islands of virulent bacteria: structure, function and impact on microbial evolution”. Molecular Microbiology. 23 (6): 1089–1097. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3101672.x. PMID 9106201. S2CID 27524815.

- Ochman H, Lawrence JG, Groisman EA (May 2000). “Lateral gene transfer and the nature of bacterial innovation”. Nature. 405 (6784): 299–304. Bibcode:2000Natur.405..299O. doi:10.1038/35012500. PMID 10830951. S2CID 85739173

- Dunning Hotopp JC (April 2011). “Horizontal gene transfer between bacteria and animals”. Trends in Genetics. 27 (4): 157–63. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2011.01.005. PMC 3068243. PMID 21334091.

- Robinson KM, Sieber KB, Dunning Hotopp JC (October 2013). “A review of bacteria-animal lateral gene transfer may inform our understanding of diseases like cancer”. PLOS Genetics. 9 (10): e1003877. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1003877. PMC 3798261. PMID 24146634.

- Keeling PJ, Palmer JD (August 2008). “Horizontal gene transfer in eukaryotic evolution”. Nature Reviews. Genetics. 9 (8): 605–18. doi:10.1038/nrg2386. PMID 18591983. S2CID 213613.

- Finan TM. Evolving insights: symbiosis islands and horizontal gene transfer. J Bacteriol. 2002 Jun;184(11):2855-6. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.11.2855-2856.2002. PMID: 12003923; PMCID: PMC135049. The research that led to the characterization of this island represents an engaging and attractive “case history,” in which initial findings from a field experiment have logically progressed to the report by Sullivan et al. in this issue of the sequence and annotation of the entire 502-kb island. This work impacts on diverse areas of microbiology, including the rhizobium-legume symbiosis, microbial ecology, and microbial evolution. The studies had their origin in 1986, when Lotus corniculatus seeds, coated with a single M. loti inoculant strain, were planted in a remote field site in New Zealand. No indigenous rhizobia capable of forming root nodules on Lotus were present in the soil, and uninoculated plants died of nitrogen starvation. Seven years later, strains isolated from nodulated Lotus plants at the site were found to be genetically diverse but share the same chromosomally located symbiotic DNA. It was subsequently shown that these “new” M. loti strains arose by transfer of a 500-kb “symbiosis island” from the original inoculant strain to nonsymbiotic mesorhizobia present in the soil. The symbiosis island was found to integrate into the phenylalanine-tRNA gene of the recipients, in a process mediated by a P4-type integrase encoded at the left end of the island. This mode of integration has been shown, or is implied, for many other elements including several PAIs. The similarities in structure and implied mechanism of transfer of the symbiosis island and other islands including PAIs are fascinating in view of the very different effects the presence of these genes has on their respective eukaryotic hosts. Thus, future research on the mechanism and factors influencing transfer of this symbiotic island may reveal information directly relevant to unraveling the transfer mechanisms of other genomic islands. The island encodes a mating pore system similar in many respects to those of plasmids found in members of the family Rhizobiaceae, indicating it is likely to transfer by conjugation; however, the genes involved in the DNA processing reactions which precede transfer are not readily apparent.

The genomes of the various Streptomyces species demonstrate remarkable plasticity, via ancient single gene duplications, block duplications (mainly at the chromosomal arms) and horizontal gene transfer. The size of their chromosome varies from 5.7-12.1 Mbps (average: 8.5 Mbps), the number of chromosomally encoded proteins varies from 4983-10,112 (average: 7130), whereas their high GC content varies from 68.8-74.7% (average: 71.7%). The 95% soft-core proteome of the genus consists of approximately 2000-2400 proteins. The pangenome is open.

- Nikolaidis, Marios; Hesketh, Andrew; Frangou, Nikoletta; Mossialos, Dimitris; Van de Peer, Yves; Oliver, Stephen G.; Amoutzias, Grigorios D. (June 2023). “A panoramic view of the genomic landscape of the genus Streptomyces”. Microbial Genomics. 9 (6). doi:10.1099/mgen.0.001028. ISSN 2057-5858. PMID 37266990. S2CID 259025020.

- McDonald, Bradon R.; Currie, Cameron R. (2017-06-06). “Lateral Gene Transfer Dynamics in the Ancient Bacterial Genus Streptomyces”. mBio. 8 (3): e00644–17. doi:10.1128/mBio.00644-17. ISSN 2150-7511. PMC 5472806. PMID 28588130.

- Caicedo-Montoya, Carlos; Manzo-Ruiz, Monserrat; Ríos-Estepa, Rigoberto (2021). “Pan-Genome of the Genus Streptomyces and Prioritization of Biosynthetic Gene Clusters With Potential to Produce Antibiotic Compounds”. Frontiers in Microbiology. 12: 677558. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2021.677558. ISSN 1664-302X. PMC 8510958. PMID 34659136.

- Otani, Hiroshi; Udwary, Daniel W.; Mouncey, Nigel J. (2022-11-07). “Comparative and pangenomic analysis of the genus Streptomyces”. Scientific Reports. 12 (1): 18909. Bibcode:2022NatSR..1218909O. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-21731-1. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 9640686. PMID 36344558.

In addition, significant genomic plasticity is observed even between strains of the same species, where the number of accessory proteins (at the species level) ranges from 250 to more than 3000. Intriguingly, a correlation has been observed between the number of carbohydrate-active enzymes and secondary metabolite biosynthetic gene clusters (siderophores, e-Polylysin and type III lanthipeptides) that are related to competition among bacteria, in Streptomyces species. Streptomycetes are major biomass degraders, mainly via their carbohydrate-active enzymes.

- Chater, Keith F.; Biró, Sandor; Lee, Kye Joon; Palmer, Tracy; Schrempf, Hildgund (March 2010). “The complex extracellular biology of Streptomyces”. FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 34 (2): 171–198. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6976.2009.00206.x. ISSN 1574-6976. PMID 20088961.

Thus, they also need to evolve an arsenal of siderophores and antimicrobial agents to suppress competition by other bacteria in these nutrient-rich environments that they create. Several evolutionary analyses have revealed that the majority of evolutionarily stable genomic elements are localized mainly at the central region of the chromosome, whereas the evolutionarily unstable elements tend to localize at the chromosomal arms.

- Nikolaidis, Marios; Hesketh, Andrew; Frangou, Nikoletta; Mossialos, Dimitris; Van de Peer, Yves; Oliver, Stephen G.; Amoutzias, Grigorios D. (June 2023). “A panoramic view of the genomic landscape of the genus Streptomyces”. Microbial Genomics. 9 (6). doi:10.1099/mgen.0.001028. ISSN 2057-5858. PMID 37266990. S2CID 259025020.

- Lorenzi, Jean-Noël; Lespinet, Olivier; Leblond, Pierre; Thibessard, Annabelle (September 2019). “Subtelomeres are fast-evolving regions of the Streptomyces linear chromosome”. Microbial Genomics. 7 (6): 000525. doi:10.1099/mgen.0.000525. ISSN 2057-5858. PMC 8627663. PMID 33749576.

- Tidjani, Abdoul-Razak; Lorenzi, Jean-Noël; Toussaint, Maxime; van Dijk, Erwin; Naquin, Delphine; Lespinet, Olivier; Bontemps, Cyril; Leblond, Pierre (2019-09-03). “Massive Gene Flux Drives Genome Diversity between Sympatric Streptomyces Conspecifics”. mBio. 10 (5): e01533–19. doi:10.1128/mBio.01533-19. ISSN 2150-7511. PMC 6722414. PMID 31481382.

- Volff, J. N.; Altenbuchner, J. (January 1998). “Genetic instability of the Streptomyces chromosome”. Molecular Microbiology. 27 (2): 239–246. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00652.x. ISSN 0950-382X. PMID 9484880. S2CID 20438399.

- Chen, Carton W.; Huang, Chih-Hung; Lee, Hsuan-Hsuan; Tsai, Hsiu-Hui; Kirby, Ralph (October 2002). “Once the circle has been broken: dynamics and evolution of Streptomyces chromosomes”. Trends in Genetics. 18 (10): 522–529. doi:10.1016/s0168-9525(02)02752-x. ISSN 0168-9525. PMID 12350342.

Thus, the chromosomal arms emerge as the part of the genome that is mainly responsible for rapid adaptation at both the species and strain level.

- Nikolaidis, Marios; Hesketh, Andrew; Frangou, Nikoletta; Mossialos, Dimitris; Van de Peer, Yves; Oliver, Stephen G.; Amoutzias, Grigorios D. (June 2023). “A panoramic view of the genomic landscape of the genus Streptomyces”. Microbial Genomics. 9 (6). doi:10.1099/mgen.0.001028. ISSN 2057-5858. PMID 37266990. S2CID 259025020.

Biotechnology

Biotechnology researchers have used Streptomyces species for heterologous expression of proteins. Traditionally, Escherichia coli was the species of choice to express eukaryotic genes, since it was well understood and easy to work with.

- Brawner M, Poste G, Rosenberg M, Westpheling J (October 1991). “Streptomyces: a host for heterologous gene expression”. Current Opinion in Biotechnology. 2 (5): 674–81. doi:10.1016/0958-1669(91)90033-2. PMID 1367716.

- Payne GF, DelaCruz N, Coppella SJ (July 1990). “Improved production of heterologous protein from Streptomyces lividans”. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 33 (4): 395–400. doi:10.1007/BF00176653. PMID 1369282. S2CID 19287805.

Expression of eukaryotic proteins in E. coli may be problematic. Sometimes, proteins do not fold properly, which may lead to insolubility, deposition in inclusion bodies, and loss of bioactivity of the product. Though E. coli strains have secretion mechanisms, these are of low efficiency and result in secretion into the periplasmic space, whereas secretion by a Gram-positive bacterium such as a Streptomyces species results in secretion directly into the extracellular medium. In addition, Streptomyces species have more efficient secretion mechanisms than E.coli. The properties of the secretion system is an advantage for industrial production of heterologously expressed protein because it simplifies subsequent purification steps and may increase yield. These properties among others make Streptomyces spp. an attractive alternative to other bacteria such as E. coli and Bacillus subtilis.

- Binnie C, Cossar JD, Stewart DI (August 1997). “Heterologous biopharmaceutical protein expression in Streptomyces”. Trends in Biotechnology. 15 (8): 315–20. doi:10.1016/S0167-7799(97)01062-7. PMID 9263479.

In addition, the inherently high genomic instability suggests that the various Streptomycetes genomes may be amenable to extensive genome reduction for the construction of synthetic minimal genomes with industrial applications.

- Nikolaidis, Marios; Hesketh, Andrew; Frangou, Nikoletta; Mossialos, Dimitris; Van de Peer, Yves; Oliver, Stephen G.; Amoutzias, Grigorios D. (June 2023). “A panoramic view of the genomic landscape of the genus Streptomyces”. Microbial Genomics. 9 (6). doi:10.1099/mgen.0.001028. ISSN 2057-5858. PMID 37266990. S2CID 259025020.

Plant pathogenic bacteria

So far, different species belonging to this genus have been found to be pathogenic to plants:[12]

- S. scabiei

- S. acidiscabies

- S. europaeiscabiei

- S. luridiscabiei

- S. niveiscabiei

- S. puniciscabiei

- S. reticuliscabiei

- S. stelliscabiei

- S. turgidiscabies (scab disease in potatoes)

- S. ipomoeae (soft rot disease in sweet potatoes)

- Streptomyces brasiliscabiei (first species identified in Brazil)[34]

- Streptomyces hilarionis and Streptomyces hayashii (new species identified in Brazil)[35]

Medicine

Streptomyces is the largest antibiotic-producing genus, producing antibacterial, antifungal, and antiparasitic drugs, and also a wide range of other bioactive compounds, such as immunosuppressants.

- Watve MG, Tickoo R, Jog MM, Bhole BD (November 2001). “How many antibiotics are produced by the genus Streptomyces?”. Archives of Microbiology. 176 (5): 386–90. doi:10.1007/s002030100345. PMID 11702082. S2CID 603765.

Almost all of the bioactive compounds produced by Streptomyces are initiated during the time coinciding with the aerial hyphal formation from the substrate mycelium.

- Chater K, Losick R (1984). “Morphological and physiological differentiation in Streptomyces“. Microbial development. Vol. 16. pp. 89–115. doi:10.1101/0.89-115 (inactive 31 December 2022). ISBN 978-0-87969-172-1. Retrieved 2012-01-19.

Antifungals

See also: Polyene antimycotic

Streptomycetes produce numerous antifungal compounds of medicinal importance, including nystatin (from S. noursei), amphotericin B (from S. nodosus), and natamycin (from S. natalensis).

- Procópio RE, Silva IR, Martins MK, Azevedo JL, Araújo JM (2012). “Antibiotics produced by Streptomyces”. The Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 16 (5): 466–71. doi:10.1016/j.bjid.2012.08.014. PMID 22975171.

Antibacterials

Members of the genus Streptomyces are the source for numerous antibacterial pharmaceutical agents; among the most important of these are:

- Chloramphenicol (from S. venezuelae)[38]

- Daptomycin (from S. roseosporus)[39]

- Fosfomycin (from S. fradiae)[40]

- Lincomycin (from S. lincolnensis)[41]

- Neomycin (from S. fradiae)[42]

- Nourseothricin[citation needed]

- Puromycin (from S. alboniger)[43]

- Streptomycin (from S. griseus)[44]

- Tetracycline (from S. rimosus and S. aureofaciens)[45]

- Oleandomycin (from S. antibioticus)[46][47][48]

- Tunicamycin (from S. torulosus)[49]

- Mycangimycin (from Streptomyces sp. SPB74 and S. antibioticus)[50]

- Boromycin (from S. antibioticus)[51]

- Bambermycin (from S. bambergiensis and S. ghanaensis, the active compound being moenomycins A and C)[52]

- Vulgamycin[53]

Clavulanic acid (from S. clavuligerus) is a drug used in combination with some antibiotics (like amoxicillin) to block and/or weaken some bacterial-resistance mechanisms by irreversible beta-lactamase inhibition. Novel antiinfectives currently being developed include Guadinomine (from Streptomyces sp. K01-0509), a compound that blocks the Type III secretion system of Gram-negative bacteria.

- Holmes TC, May AE, Zaleta-Rivera K, Ruby JG, Skewes-Cox P, Fischbach MA, et al. (October 2012). “Molecular insights into the biosynthesis of guadinomine: a type III secretion system inhibitor”. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 134 (42): 17797–806. doi:10.1021/ja308622d. PMC 3483642. PMID 23030602.

Antiparasitic drugs

S. avermitilis is responsible for the production of one of the most widely employed drugs against nematode and arthropod infestations, avermectin, and thus its derivatives including ivermectin.

- Martín, Juan F; Rodríguez-García, Antonio; Liras, Paloma (2017-03-15). “The master regulator PhoP coordinates phosphate and nitrogen metabolism, respiration, cell differentiation and antibiotic biosynthesis: comparison in Streptomyces coelicolor and Streptomyces avermitilis“. The Journal of Antibiotics. Japan Antibiotics Research Association (Nature Portfolio). 70 (5): 534–541. doi:10.1038/ja.2017.19. ISSN 0021-8820. PMID 28293039. S2CID 1881648.

Other

Less commonly, streptomycetes produce compounds used in other medical treatments: migrastatin (from S. platensis) and bleomycin (from S. verticillus) are antineoplastic (anticancer) drugs; boromycin (from S. antibioticus) exhibits antiviral activity against the HIV-1 strain of HIV, as well as antibacterial activity. Staurosporine (from S. staurosporeus) also has a range of activities from antifungal to antineoplastic (via the inhibition of protein kinases).

S. hygroscopicus and S. viridochromogenes produce the natural herbicide bialaphos. Bialaphos is a protoxin and nontoxic as is. When it is metabolized by the plant, the glutamic acid analog glufosinate is released which inhibits glutamine synthetase. This results in the accumulation of ammonium and disruption of primary metabolism. Bialaphos is made up of two alanine residues and glufosinate, and is commonly used as a selection marker in plants. Glufosinate is a United States Environmental Protection Agency EPA registered chemical. It is also a California registered chemical. It is not banned in the country and it is not a PIC pesticide. There are no exposure limits established by OSHA or the American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists. Glufosinate is not approved for use as an herbicide in Europe; it was last reviewed in 2007 and that registration expired in 2018. It has been withdrawn from the French market since October 24, 2017 by the Agence nationale de sécurité sanitaire de l’alimentation, de l’environnement et du travail due to its classification as a possible reprotoxic chemical (R1b). Reproductive toxicity refers to the potential risk from a given chemical, physical or biologic agent to adversely affect both male and female fertility as well as offspring development. Reproductive toxicants may adversely affect sexual function, ovarian failure, fertility as well as causing developmental toxicity in the offspring. Resistance plasmids include pGreenII 0229 and pGreenII 0229 62-SK. pGreenII 0229 is derived from pGreenII 0000, a nos-bar cassette has been inserted into the HpaI site of the left border, providing resistance to bialaphos or phosphinothricin during plant transformation selection. pGreenII 0229 62-SK is derived from pGreenII 0229, the LacZ blue/white cloning selection has been replaced with a 35S-MCS–CaMV cassette that allows the insertion of a gene of interest into a 35S overexpression cassette. Phosalacine is a related tripeptide.

- Murakami, Takeshi; Anzai, Hiroyuki; Imai, Satoshi; Satoh, Atsuyuki; Nagaoka, Kozo; Thompson, Charles J. (1986). “The bialaphos biosynthetic genes of Streptomyces hygroscopicus: Molecular cloning and characterization of the gene cluster”. MGG Molecular & General Genetics. 205: 42–53. doi:10.1007/BF02428031. S2CID 32983239.

- Duke, Stephen O.; Dayan, Franck E. (2011). “Modes of Action of Microbially-Produced Phytotoxins”. Toxins (Basel). 3 (8): 1038–1064. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.288.3457. doi:10.3390/toxins3081038. PMC 3202864. PMID 22069756.

- “Bialaphos as plant gene selector” (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 October 2014. Retrieved 20 June 2012.

- “Chemical Identification and Company Information : DL-Phosphinothricin, Monoammonium Salt” (PDF). Phytotechlab.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-04-25.

- The Rotterdam Convention on Prior Informed Consent (PIC)

- European Commission. Glufosinate in EU Pesticides Database Page accessed August 7, 2015

- Anses. L’Anses procède au retrait de l’autorisation de mise sur le marché du Basta F1, un produit phytopharmaceutique à base de glufosinate Page accessed October 26, 2017

- Occupational Health and Safety Administration. “Reproductive Hazards”. osha.gov. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

- ^

- “Regulation (EC) No 1272/2008 of the EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT and of the COUNCIL”. Official Journal of the European Union. 16 December 2008.

Annex I, section 3.7 labelling and packaging of substances and mixtures, amending and repealing Directives 67/548/EEC and 1999/45/EC, and amending Regulation (EC) No 1907/2006.

- International Programme on Chemical Safety (2001). “Principles For Evaluating Health Risks To Reproduction Associated With Exposure To Chemicals”. Environmental Health Criteria. Geneva: World Health Organization. 225.

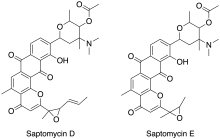

Saptomycins are chemical compounds isolated from Streptomyces.

- Abe, N.; Nakakita, Y.; Nakamura, T.; Enoki, N.; Uchida, H.; Munekata, M. (1993). “Novel antitumor antibiotics, saptomycins. I. Taxonomy of the producing organism, fermentation, HPLC analysis and biological activities”. The Journal of Antibiotics. 46 (10): 1530–5. doi:10.7164/antibiotics.46.1530. PMID 8244880.

Symbiosis

Sirex wasps cannot perform all of their own cellulolytic functions and so some Streptomyces do so in symbiosis with the wasps. Book et al. have investigated several of these symbioses. Book et al., 2014 and Book et al., 2016 identify several lytic isolates. The 2016 study isolates Streptomyces sp. Amel2xE9 and Streptomyces sp. LamerLS-31b and finds that they are equal in activity to the previously identified Streptomyces sp. SirexAA-E.

- Li, Hongjie; Young, Soleil E.; Poulsen, Michael; Currie, Cameron R. (2021-01-07). “Symbiont-Mediated Digestion of Plant Biomass in Fungus-Farming Insects”. Annual Review of Entomology. Annual Reviews. 66 (1): 297–316. doi:10.1146/annurev-ento-040920-061140. ISSN 0066-4170. OSTI 1764729. PMID 32926791. S2CID 221724225.

See also

- Antimycin A – Chemical compound produced by Stroptomyces used as a piscicide

- Geosmin – Chemical compound responsible for the characteristic odour of earth

- Streptomyces isolates

References

- Euzéby JP, Parte AC. “Streptomyces“. List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature (LPSN). Retrieved June 9, 2021.

- Van der Meij, A., Willemse, J., Schneijderberg, M.A., Geurts, R., Raaijmakers, J.M. and van Wezel, G.P. (2018) “Inter-and intracellular colonization of Arabidopsis roots by endophytic actinobacteria and the impact of plant hormones on their antimicrobial activity”. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, 111(5): 679–690. doi:10.1007/s10482-018-1014-z

- Kämpfer P (2006). “The Family Streptomycetaceae, Part I: Taxonomy”. In Dworkin M, Falkow S, Rosenberg E, Schleifer KH, Stackebrandt E (eds.). The Prokaryotes. pp. 538–604. doi:10.1007/0-387-30743-5_22. ISBN 978-0-387-25493-7.

- Euzéby JP (2008). “Genus Streptomyces”. List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature. Retrieved 2008-09-28.

- Nikolaidis, Marios; Hesketh, Andrew; Frangou, Nikoletta; Mossialos, Dimitris; Van de Peer, Yves; Oliver, Stephen G.; Amoutzias, Grigorios D. (June 2023). “A panoramic view of the genomic landscape of the genus Streptomyces”. Microbial Genomics. 9 (6). doi:10.1099/mgen.0.001028. ISSN 2057-5858. PMID 37266990. S2CID 259025020.

- “Genus: Streptomyces”. www.bacterio.net. Retrieved 2023-06-21.

- Madigan M, Martinko J, eds. (2005). Brock Biology of Microorganisms (11th ed.). Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-144329-7.[page needed]

- John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, ed. (2001-05-30). eLS (1 ed.). Wiley. doi:10.1002/9780470015902.a0020392.pub2. ISBN 978-0-470-01617-6.

- Kieser T, Bibb MJ, Buttner MJ, Chater KF, Hopwood DA (2000). Practical Streptomyces Genetics (2nd ed.). Norwich, England: John Innes Foundation. ISBN 978-0-7084-0623-6.[page needed]

- Bibb MJ (December 2013). “Understanding and manipulating antibiotic production in actinomycetes”. Biochemical Society Transactions. 41 (6): 1355–64. doi:10.1042/BST20130214. PMID 24256223.

- Anderson AS, Wellington EM (May 2001). “The taxonomy of Streptomyces and related genera”. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 51 (Pt 3): 797–814. doi:10.1099/00207713-51-3-797. PMID 11411701.

- Labeda DP (October 2011). “Multilocus sequence analysis of phytopathogenic species of the genus Streptomyces”. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 61 (Pt 10): 2525–2531. doi:10.1099/ijs.0.028514-0. PMID 21112986.

- Zhang Z, Wang Y, Ruan J (October 1997). “A proposal to revive the genus Kitasatospora (Omura, Takahashi, Iwai, and Tanaka 1982)”. International Journal of Systematic Bacteriology. 47 (4): 1048–54. doi:10.1099/00207713-47-4-1048. PMID 9336904.

- Kim SB, Lonsdale J, Seong CN, Goodfellow M (2003). “Streptacidiphilus gen. nov., acidophilic actinomycetes with wall chemotype I and emendation of the family Streptomycetaceae (Waksman and Henrici (1943)AL) emend. Rainey et al. 1997”. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. 83 (2): 107–16. doi:10.1023/A:1023397724023. PMID 12785304. S2CID 12901116.

- Chater K, Losick R (1984). “Morphological and physiological differentiation in Streptomyces“. Microbial development. Vol. 16. pp. 89–115. doi:10.1101/0.89-115 (inactive 31 December 2022). ISBN 978-0-87969-172-1. Retrieved 2012-01-19.

- Dietz A, Mathews J (March 1971). “Classification of Streptomyces spore surfaces into five groups”. Applied Microbiology. 21 (3): 527–33. doi:10.1128/AEM.21.3.527-533.1971. PMC 377216. PMID 4928607.

- Bentley SD, Chater KF, Cerdeño-Tárraga AM, Challis GL, Thomson NR, James KD, et al. (May 2002). “Complete genome sequence of the model actinomycete Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2)”. Nature. 417 (6885): 141–7. Bibcode:2002Natur.417..141B. doi:10.1038/417141a. PMID 12000953. S2CID 4430218.

- Chater KF, Biró S, Lee KJ, Palmer T, Schrempf H (March 2010). “The complex extracellular biology of Streptomyces”. FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 34 (2): 171–98. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6976.2009.00206.x. PMID 20088961.

- Jeong Y, Kim JN, Kim MW, Bucca G, Cho S, Yoon YJ, et al. (June 2016). “The dynamic transcriptional and translational landscape of the model antibiotic producer Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2)”. Nature Communications. 7 (1): 11605. Bibcode:2016NatCo…711605J. doi:10.1038/ncomms11605. PMC 4895711. PMID 27251447.

- Ikeda H, Ishikawa J, Hanamoto A, Shinose M, Kikuchi H, Shiba T, et al. (May 2003). “Complete genome sequence and comparative analysis of the industrial microorganism Streptomyces avermitilis”. Nature Biotechnology. 21 (5): 526–31. doi:10.1038/nbt820. PMID 12692562.

- Dyson P (1 January 2011). Streptomyces: Molecular Biology and Biotechnology. Horizon Scientific Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-904455-77-6. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- “Streptomyces scabies”. Sanger Institute. Retrieved 2001-02-26.

- McDonald, Bradon R.; Currie, Cameron R. (2017-06-06). “Lateral Gene Transfer Dynamics in the Ancient Bacterial Genus Streptomyces”. mBio. 8 (3): e00644–17. doi:10.1128/mBio.00644-17. ISSN 2150-7511. PMC 5472806. PMID 28588130.

- Caicedo-Montoya, Carlos; Manzo-Ruiz, Monserrat; Ríos-Estepa, Rigoberto (2021). “Pan-Genome of the Genus Streptomyces and Prioritization of Biosynthetic Gene Clusters With Potential to Produce Antibiotic Compounds”. Frontiers in Microbiology. 12: 677558. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2021.677558. ISSN 1664-302X. PMC 8510958. PMID 34659136.

- Otani, Hiroshi; Udwary, Daniel W.; Mouncey, Nigel J. (2022-11-07). “Comparative and pangenomic analysis of the genus Streptomyces”. Scientific Reports. 12 (1): 18909. Bibcode:2022NatSR..1218909O. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-21731-1. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 9640686. PMID 36344558.

- Chater, Keith F.; Biró, Sandor; Lee, Kye Joon; Palmer, Tracy; Schrempf, Hildgund (March 2010). “The complex extracellular biology of Streptomyces”. FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 34 (2): 171–198. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6976.2009.00206.x. ISSN 1574-6976. PMID 20088961.

- Lorenzi, Jean-Noël; Lespinet, Olivier; Leblond, Pierre; Thibessard, Annabelle (September 2019). “Subtelomeres are fast-evolving regions of the Streptomyces linear chromosome”. Microbial Genomics. 7 (6): 000525. doi:10.1099/mgen.0.000525. ISSN 2057-5858. PMC 8627663. PMID 33749576.

- Tidjani, Abdoul-Razak; Lorenzi, Jean-Noël; Toussaint, Maxime; van Dijk, Erwin; Naquin, Delphine; Lespinet, Olivier; Bontemps, Cyril; Leblond, Pierre (2019-09-03). “Massive Gene Flux Drives Genome Diversity between Sympatric Streptomyces Conspecifics”. mBio. 10 (5): e01533–19. doi:10.1128/mBio.01533-19. ISSN 2150-7511. PMC 6722414. PMID 31481382.

- Volff, J. N.; Altenbuchner, J. (January 1998). “Genetic instability of the Streptomyces chromosome”. Molecular Microbiology. 27 (2): 239–246. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00652.x. ISSN 0950-382X. PMID 9484880. S2CID 20438399.

- Chen, Carton W.; Huang, Chih-Hung; Lee, Hsuan-Hsuan; Tsai, Hsiu-Hui; Kirby, Ralph (October 2002). “Once the circle has been broken: dynamics and evolution of Streptomyces chromosomes”. Trends in Genetics. 18 (10): 522–529. doi:10.1016/s0168-9525(02)02752-x. ISSN 0168-9525. PMID 12350342.

- Brawner M, Poste G, Rosenberg M, Westpheling J (October 1991). “Streptomyces: a host for heterologous gene expression”. Current Opinion in Biotechnology. 2 (5): 674–81. doi:10.1016/0958-1669(91)90033-2. PMID 1367716.

- Payne GF, DelaCruz N, Coppella SJ (July 1990). “Improved production of heterologous protein from Streptomyces lividans”. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 33 (4): 395–400. doi:10.1007/BF00176653. PMID 1369282. S2CID 19287805.

- Binnie C, Cossar JD, Stewart DI (August 1997). “Heterologous biopharmaceutical protein expression in Streptomyces”. Trends in Biotechnology. 15 (8): 315–20. doi:10.1016/S0167-7799(97)01062-7. PMID 9263479.

- Corrêa, Daniele Bussioli Alves; do Amaral, Danilo Trabuco; da Silva, Márcio José; Destéfano, Suzete Aparecida Lanza (July 2021). “Streptomyces brasiliscabiei, a new species causing potato scab in south Brazil”. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek. 114 (7): 913–931. doi:10.1007/s10482-021-01566-y.

- Vitor, Lucas; Amaral, Danilo Trabuco; Corrêa, Daniele Bussioli Alves; Ferreira-Tonin, Mariana; Lucon, Emanuel Torres; Appy, Mariana Pereira; Tomaseto, Alex Augusto; Destéfano, Suzete Aparecida Lanza (15 June 2023). “Streptomyces hilarionis sp. nov. and Streptomyces hayashii sp. nov., two new strains associated with potato scab in Brazil”. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 73 (6). doi:10.1099/ijsem.0.005916.

- Watve MG, Tickoo R, Jog MM, Bhole BD (November 2001). “How many antibiotics are produced by the genus Streptomyces?”. Archives of Microbiology. 176 (5): 386–90. doi:10.1007/s002030100345. PMID 11702082. S2CID 603765.

- Procópio RE, Silva IR, Martins MK, Azevedo JL, Araújo JM (2012). “Antibiotics produced by Streptomyces”. The Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 16 (5): 466–71. doi:10.1016/j.bjid.2012.08.014. PMID 22975171.

- Akagawa H, Okanishi M, Umezawa H (October 1975). “A plasmid involved in chloramphenicol production in Streptomyces venezuelae: evidence from genetic mapping”. Journal of General Microbiology. 90 (2): 336–46. doi:10.1099/00221287-90-2-336. PMID 1194895.

- Miao V, Coëffet-LeGal MF, Brian P, Brost R, Penn J, Whiting A, et al. (May 2005). “Daptomycin biosynthesis in Streptomyces roseosporus: cloning and analysis of the gene cluster and revision of peptide stereochemistry”. Microbiology. 151 (Pt 5): 1507–1523. doi:10.1099/mic.0.27757-0. PMID 15870461.

- Woodyer RD, Shao Z, Thomas PM, Kelleher NL, Blodgett JA, Metcalf WW, et al. (November 2006). “Heterologous production of fosfomycin and identification of the minimal biosynthetic gene cluster”. Chemistry & Biology. 13 (11): 1171–82. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.09.007. PMID 17113999.

- Peschke U, Schmidt H, Zhang HZ, Piepersberg W (June 1995). “Molecular characterization of the lincomycin-production gene cluster of Streptomyces lincolnensis 78-11”. Molecular Microbiology. 16 (6): 1137–56. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02338.x. PMID 8577249. S2CID 45162659.

- Dulmage HT (March 1953). “The production of neomycin by Streptomyces fradiae in synthetic media”. Applied Microbiology. 1 (2): 103–6. doi:10.1128/AEM.1.2.103-106.1953. PMC 1056872. PMID 13031516.

- Sankaran L, Pogell BM (December 1975). “Biosynthesis of puromycin in Streptomyces alboniger: regulation and properties of O-demethylpuromycin O-methyltransferase”. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 8 (6): 721–32. doi:10.1128/AAC.8.6.721. PMC 429454. PMID 1211926.

- Distler J, Ebert A, Mansouri K, Pissowotzki K, Stockmann M, Piepersberg W (October 1987). “Gene cluster for streptomycin biosynthesis in Streptomyces griseus: nucleotide sequence of three genes and analysis of transcriptional activity”. Nucleic Acids Research. 15 (19): 8041–56. doi:10.1093/nar/15.19.8041. PMC 306325. PMID 3118332.

- Nelson M, Greenwald RA, Hillen W (2001). Tetracyclines in biology, chemistry and medicine. Birkhäuser. pp. 8–. ISBN 978-3-7643-6282-9. Retrieved 17 January 2012.

- “What are Streptomycetes?”. Hosenkin Lab; Hiroshima-University. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 10 August 2015.

- Swan DG, Rodríguez AM, Vilches C, Méndez C, Salas JA (February 1994). “Characterisation of a Streptomyces antibioticus gene encoding a type I polyketide synthase which has an unusual coding sequence”. Molecular & General Genetics. 242 (3): 358–62. doi:10.1007/BF00280426. PMID 8107683. S2CID 2195072.

- “Finto: MeSH: Streptomyces antibioticus”. finto: Finnish Thesaurus and Ontology Service. Retrieved 10 August 2015.

- Atta HM (January 2015). “Biochemical studies on antibiotic production from Streptomyces sp.: Taxonomy, fermentation, isolation and biological properties”. Journal of Saudi Chemical Society. 19 (1): 12–22. doi:10.1016/j.jscs.2011.12.011.

- Oh DC, Scott JJ, Currie CR, Clardy J (February 2009). “Mycangimycin, a polyene peroxide from a mutualist Streptomyces sp”. Organic Letters. 11 (3): 633–6. doi:10.1021/ol802709x. PMC 2640424. PMID 19125624.

- Chen TS, Chang CJ, Floss HG (June 1981). “Biosynthesis of boromycin”. The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 46 (13): 2661–2665. doi:10.1021/jo00326a010.

- “CID=53385491”. PubChem Compound Database. National Center for Biotechnology Information. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- Babczinski, Peter; Dorgerloh, Michael; Löbberding, Antonius; Santel, Hans-Joachim; Schmidt, Robert R.; Schmitt, Peter; Wünsche, Christian (1991). “Herbicidal activity and mode of action of vulgamycin”. Pesticide Science. 33 (4): 439–446. doi:10.1002/ps.2780330406.

- Holmes TC, May AE, Zaleta-Rivera K, Ruby JG, Skewes-Cox P, Fischbach MA, et al. (October 2012). “Molecular insights into the biosynthesis of guadinomine: a type III secretion system inhibitor”. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 134 (42): 17797–806. doi:10.1021/ja308622d. PMC 3483642. PMID 23030602.

- Martín, Juan F; Rodríguez-García, Antonio; Liras, Paloma (2017-03-15). “The master regulator PhoP coordinates phosphate and nitrogen metabolism, respiration, cell differentiation and antibiotic biosynthesis: comparison in Streptomyces coelicolor and Streptomyces avermitilis“. The Journal of Antibiotics. Japan Antibiotics Research Association (Nature Portfolio). 70 (5): 534–541. doi:10.1038/ja.2017.19. ISSN 0021-8820. PMID 28293039. S2CID 1881648.

- Abe, N.; Nakakita, Y.; Nakamura, T.; Enoki, N.; Uchida, H.; Munekata, M. (1993). “Novel antitumor antibiotics, saptomycins. I. Taxonomy of the producing organism, fermentation, HPLC analysis and biological activities”. The Journal of Antibiotics. 46 (10): 1530–5. doi:10.7164/antibiotics.46.1530. PMID 8244880.

- Li, Hongjie; Young, Soleil E.; Poulsen, Michael; Currie, Cameron R. (2021-01-07). “Symbiont-Mediated Digestion of Plant Biomass in Fungus-Farming Insects”. Annual Review of Entomology. Annual Reviews. 66 (1): 297–316. doi:10.1146/annurev-ento-040920-061140. ISSN 0066-4170. OSTI 1764729. PMID 32926791. S2CID 221724225.

- Murakami, Takeshi; Anzai, Hiroyuki; Imai, Satoshi; Satoh, Atsuyuki; Nagaoka, Kozo; Thompson, Charles J. (1986). “The bialaphos biosynthetic genes of Streptomyces hygroscopicus: Molecular cloning and characterization of the gene cluster”. MGG Molecular & General Genetics. 205: 42–53. doi:10.1007/BF02428031. S2CID 32983239.

- Duke, Stephen O.; Dayan, Franck E. (2011). “Modes of Action of Microbially-Produced Phytotoxins”. Toxins (Basel). 3 (8): 1038–1064. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.288.3457. doi:10.3390/toxins3081038. PMC 3202864. PMID 22069756.

- “Bialaphos as plant gene selector” (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 October 2014. Retrieved 20 June 2012.

- “Chemical Identification and Company Information : DL-Phosphinothricin, Monoammonium Salt” (PDF). Phytotechlab.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-04-25.

- The Rotterdam Convention on Prior Informed Consent (PIC)

- European Commission. Glufosinate in EU Pesticides Database Page accessed August 7, 2015

- Anses. L’Anses procède au retrait de l’autorisation de mise sur le marché du Basta F1, un produit phytopharmaceutique à base de glufosinate Page accessed October 26, 2017

- Occupational Health and Safety Administration. “Reproductive Hazards”. osha.gov. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

- ^

- “Regulation (EC) No 1272/2008 of the EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT and of the COUNCIL”. Official Journal of the European Union. 16 December 2008.

Annex I, section 3.7 labelling and packaging of substances and mixtures, amending and repealing Directives 67/548/EEC and 1999/45/EC, and amending Regulation (EC) No 1907/2006.

- International Programme on Chemical Safety (2001). “Principles For Evaluating Health Risks To Reproduction Associated With Exposure To Chemicals”. Environmental Health Criteria. Geneva: World Health Organization. 225.

Further reading

- Baumberg S (1991). Genetics and Product Formation in Streptomyces. Kluwer Academic. ISBN 978-0-306-43885-1.

- Gunsalus IC (1986). Bacteria: Antibiotic-producing Streptomyces. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-307209-2.

- Hopwood DA (2007). Streptomyces in Nature and Medicine: The Antibiotic Makers. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-515066-7.

- Dyson P, ed. (2011). Streptomyces: Molecular Biology and Biotechnology. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-77-6.

- Scott AJ, LaDou J (2001-04-16). “Biological Rhythms, Shiftwork, and Occupational Health”. Patty’s Toxicology. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. doi:10.1002/0471435139.tox107. ISBN 978-0-471-12547-1.

External links

- “Current research on Streptomyces coelicolor“. Norwich Research Park. 3 January 2018.

- “Some current Streptomyces Research & Methods / Protocols / Resources”. www.openwetware.org.

- “S. avermitilis genome homepage”. Kitasato Institute for Life Sciences.

- “S. coelicolor A3(2) genome homepage”. Sanger Institute.

- “Streptomyces.org.uk homepage”. John Innes Centre.

- “StrepDB – the Streptomyces genomes annotation browser”.

- “Streptomyces Genome Projects”. Genomes OnLine Database.

Leave a Reply