Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 1 Local Links

Reference for subtitle: Finamor IA, Bressan CA, Torres-Cuevas I, Rius-Pérez S, da Veiga M, Rocha MI, Pavanato MA, Pérez S. Long-Term Aspartame Administration Leads to Fibrosis, Inflammasome Activation, and Gluconeogenesis Impairment in the Liver of Mice. Biology. 2021; 10(2):82. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology10020082

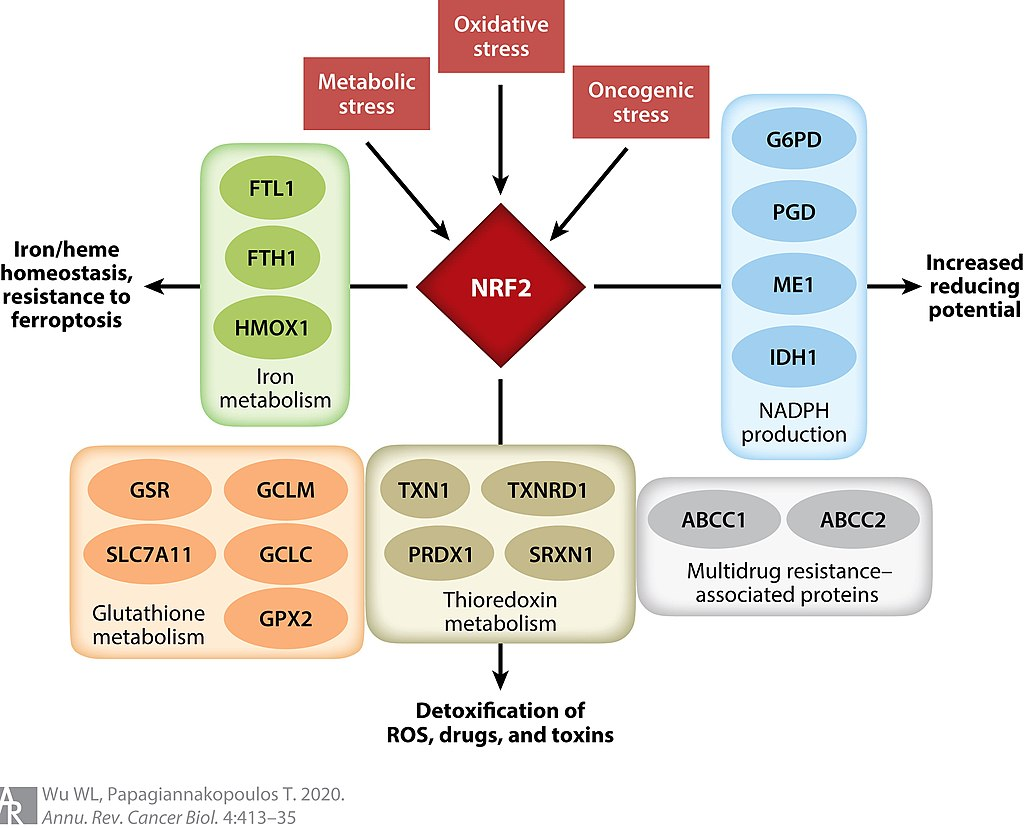

Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2), also known as nuclear factor erythroid-derived 2-like 2, is a transcription factor that in humans is encoded by the NFE2L2 gene. NRF2 is a basic leucine zipper (bZIP) protein that may regulate the expression of antioxidant proteins that protect against oxidative damage triggered by injury and inflammation, according to preliminary research. In vitro, NRF2 binds to antioxidant response elements (AREs) in the promoter regions of genes encoding cytoprotective proteins. NRF2 induces the expression of heme oxygenase 1 in vitro leading to an increase in phase II enzymes. NRF2 also inhibits the NLRP3 inflammasome.

- Moi P, Chan K, Asunis I, Cao A, Kan YW (October 1994). “Isolation of NF-E2-related factor 2 (NRF2), a NF-E2-like basic leucine zipper transcriptional activator that binds to the tandem NF-E2/AP1 repeat of the beta-globin locus control region”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 91 (21): 9926–30. Bibcode:1994PNAS…91.9926M. doi:10.1073/pnas.91.21.9926. PMC 44930. PMID 7937919

- Gold R, Kappos L, Arnold DL, Bar-Or A, Giovannoni G, Selmaj K, et al. (September 2012). “Placebo-controlled phase 3 study of oral BG-12 for relapsing multiple sclerosis”. The New England Journal of Medicine. 367 (12): 1098–107. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1114287. hdl:2078.1/124401. PMID 22992073.

- Gureev AP, Popov VN, Starkov AA (2020). “Crosstalk between the mTOR and Nrf2/ARE signaling pathways as a target in the improvement of long-term potentiation”. Experimental Gerontology. 328: 113285. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2020.113285. PMC 7145749. PMID 32165256.

- Zhu Y, Yang Q, Liu H, Chen W (2020). “Phytochemical compounds targeting on Nrf2 for chemoprevention in colorectal cancer”. European Journal of Pharmacology. 887: 173588. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2020.173588. PMID 32961170. S2CID 221863319.

- Ahmed S, Luo L, Tang X (2017). “Nrf2 signaling pathway: Pivotal roles in inflammation”. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) – Molecular Basis of Disease. 1863 (2): 585–597. doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2016.11.005. PMID 27825853.

NRF2 appears to participate in a complex regulatory network and performs a pleiotropic role in the regulation of metabolism, inflammation, autophagy, proteostasis, mitochondrial physiology, and immune responses. Several drugs that stimulate the NFE2L2 pathway are being studied for treatment of diseases that are caused by oxidative stress.

- Gold R, Kappos L, Arnold DL, Bar-Or A, Giovannoni G, Selmaj K, et al. (September 2012). “Placebo-controlled phase 3 study of oral BG-12 for relapsing multiple sclerosis”. The New England Journal of Medicine. 367 (12): 1098–107. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1114287. hdl:2078.1/124401. PMID 22992073.

- He F, Ru X, Wen T (January 2020). “NRF2, a Transcription Factor for Stress Response and Beyond”. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 21 (13): 4777. doi:10.3390/ijms21134777. PMC 7369905. PMID 32640524.

- Dodson M, de la Vega MR, Cholanians AB, Schmidlin CJ, Chapman E, Zhang DD (January 2019). “Modulating NRF2 in Disease: Timing Is Everything”. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology. 59: 555–575. doi:10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010818-021856. PMC 6538038. PMID 30256716.

A mechanism for hormetic dose responses is proposed in which Nrf2 may serve as an hormetic mediator that mediates a vast spectrum of chemopreventive processes.

- Calabrese EJ, Kozumbo WJ (May 2021). “The hormetic dose-response mechanism: Nrf2 activation”. Pharmacological Research. 167: 105526. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2021.105526. PMID 33667690. S2CID 232130837.

Structure

NRF2 is a basic leucine zipper (bZip) transcription factor with a Cap “n” Collar (CNC) structure. NRF2 possesses seven highly conserved domains called NRF2-ECH homology (Neh) domains. The Neh1 domain is a CNC-bZIP domain that allows Nrf2 to heterodimerize with small Maf proteins (MAFF, MAFG, MAFK). The Neh2 domain allows for binding of NRF2 to its cytosolic repressor Keap1. The Neh3 domain may play a role in NRF2 protein stability and may act as a transactivation domain, interacting with component of the transcriptional apparatus. The Neh4 and Neh5 domains also act as transactivation domains, but bind to a different protein called cAMP Response Element Binding Protein (CREB), which possesses intrinsic histone acetyltransferase activity. The Neh6 domain may contain a degron that is involved in a redox-insensitive process of degradation of NRF2. This occurs even in stressed cells, which normally extend the half-life of NRF2 protein relative to unstressed conditions by suppressing other degradation pathways. The “Neh7” domain is involved in the repression of Nrf2 transcriptional activity by the retinoid X receptor α through a physical association between the two proteins.

- Moi P, Chan K, Asunis I, Cao A, Kan YW (October 1994). “Isolation of NF-E2-related factor 2 (NRF2), a NF-E2-like basic leucine zipper transcriptional activator that binds to the tandem NF-E2/AP1 repeat of the beta-globin locus control region”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 91 (21): 9926–30. Bibcode:1994PNAS…91.9926M. doi:10.1073/pnas.91.21.9926. PMC 44930. PMID 7937919

- Motohashi H, Katsuoka F, Engel JD, Yamamoto M (April 2004). “Small Maf proteins serve as transcriptional cofactors for keratinocyte differentiation in the Keap1-Nrf2 regulatory pathway”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 101 (17): 6379–84. Bibcode:2004PNAS..101.6379M. doi:10.1073/pnas.0305902101. PMC 404053. PMID 15087497.

- Motohashi H, Yamamoto M (November 2004). “Nrf2-Keap1 defines a physiologically important stress response mechanism”. Trends in Molecular Medicine. 10 (11): 549–57. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2004.09.003. PMID 15519281.

- Nioi P, Nguyen T, Sherratt PJ, Pickett CB (December 2005). “The carboxy-terminal Neh3 domain of Nrf2 is required for transcriptional activation”. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 25 (24): 10895–906. doi:10.1128/MCB.25.24.10895-10906.2005. PMC 1316965. PMID 16314513.

- McMahon M, Thomas N, Itoh K, Yamamoto M, Hayes JD (July 2004). “Redox-regulated turnover of Nrf2 is determined by at least two separate protein domains, the redox-sensitive Neh2 degron and the redox-insensitive Neh6 degron”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 279 (30): 31556–67. doi:10.1074/jbc.M403061200. PMID 15143058.

- Tonelli C, Chio II, Tuveson DA (December 2018). “Transcriptional Regulation by Nrf2”. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling. 29 (17): 1727–1745. doi:10.1089/ars.2017.7342. PMC 6208165. PMID 28899199.

Localization and function

NFE2L2 and other genes, such as NFE2, NFE2L1 and NFE2L3, encode basic leucine zipper (bZIP) transcription factors. They share highly conserved regions that are distinct from other bZIP families, such as JUN and FOS, although remaining regions have diverged considerably from each other.

- Chan JY, Cheung MC, Moi P, Chan K, Kan YW (March 1995). “Chromosomal localization of the human NF-E2 family of bZIP transcription factors by fluorescence in situ hybridization”. Human Genetics. 95 (3): 265–9. doi:10.1007/BF00225191. PMID 7868116. S2CID 23774837.

- “Entrez Gene: NFE2L2 nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2”.

Under normal or unstressed conditions, NRF2 is kept in the cytoplasm by a cluster of proteins that degrade it quickly. Under oxidative stress, NRF2 is not degraded, but instead travels to the nucleus where it binds to a DNA promoter and initiates transcription of antioxidative genes and their proteins.

NRF2 is kept in the cytoplasm by Kelch like-ECH-associated protein 1 (KEAP1) and Cullin 3, which degrade NRF2 by ubiquitination. Cullin 3 ubiquitinates NRF2, while Keap1 is a substrate adaptor protein that facilitates the reaction. Once NRF2 is ubiquitinated, it is transported to the proteasome, where it is degraded and its components recycled. Under normal conditions, NRF2 has a half-life of only 20 minutes. Oxidative stress or electrophilic stress disrupts critical cysteine residues in Keap1, disrupting the Keap1-Cul3 ubiquitination system. When NRF2 is not ubiquitinated, it builds up in the cytoplasm, and translocates into the nucleus. In the nucleus, it combines (forms a heterodimer) with one of small Maf proteins (MAFF, MAFG, MAFK) and binds to the antioxidant response element (ARE) in the upstream promoter region of many antioxidative genes, and initiates their transcription.

- Itoh K, Wakabayashi N, Katoh Y, Ishii T, Igarashi K, Engel JD, Yamamoto M (January 1999). “Keap1 represses nuclear activation of antioxidant responsive elements by Nrf2 through binding to the amino-terminal Neh2 domain”. Genes & Development. 13 (1): 76–86. doi:10.1101/gad.13.1.76. PMC 316370. PMID 9887101.

- Kobayashi A, Kang MI, Okawa H, Ohtsuji M, Zenke Y, Chiba T, et al. (August 2004). “Oxidative stress sensor Keap1 functions as an adaptor for Cul3-based E3 ligase to regulate proteasomal degradation of Nrf2”. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 24 (16): 7130–9. doi:10.1128/MCB.24.16.7130-7139.2004. PMC 479737. PMID 15282312.

- Yamamoto T, Suzuki T, Kobayashi A, Wakabayashi J, Maher J, Motohashi H, Yamamoto M (April 2008). “Physiological significance of reactive cysteine residues of Keap1 in determining Nrf2 activity”. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 28 (8): 2758–70. doi:10.1128/MCB.01704-07. PMC 2293100. PMID 18268004.

- Sekhar KR, Rachakonda G, Freeman ML (April 2010). “Cysteine-based regulation of the CUL3 adaptor protein Keap1”. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 244 (1): 21–6. doi:10.1016/j.taap.2009.06.016. PMC 2837771. PMID 19560482.

- Itoh K, Chiba T, Takahashi S, Ishii T, Igarashi K, Katoh Y, et al. (July 1997). “An Nrf2/small Maf heterodimer mediates the induction of phase II detoxifying enzyme genes through antioxidant response elements”. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 236 (2): 313–22. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1997.6943. PMID 9240432.

Target genes

Activation of NRF2 induces the transcription of genes encoding cytoprotective proteins. These include:

- NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase 1 (Nqo1) is a prototypical NRF2 target protein which catalyzes the reduction and detoxification of highly reactive quinones that can cause redox cycling and oxidative stress.

- Venugopal R, Jaiswal AK (December 1996). “Nrf1 and Nrf2 positively and c-Fos and Fra1 negatively regulate the human antioxidant response element-mediated expression of NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase1 gene”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 93 (25): 14960–5. Bibcode:1996PNAS…9314960V. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.25.14960. PMC 26245. PMID 8962164

- Glutamate-cysteine ligase catalytic subunit (GCLC) and glutamate-cysteine ligase regulatory subunit (GCLM) form a heterodimer, which is the rate-limiting step in the synthesis of glutathione (GSH), a very powerful endogenous antioxidant. Both Gclc and Gclm are characteristic NRF2 target genes, which establish NRF2 as a regulator of glutathione, one of the most important antioxidants in the body.

- Solis WA, Dalton TP, Dieter MZ, Freshwater S, Harrer JM, He L, et al. (May 2002). “Glutamate-cysteine ligase modifier subunit: mouse Gclm gene structure and regulation by agents that cause oxidative stress”. Biochemical Pharmacology. 63 (9): 1739–54. doi:10.1016/S0006-2952(02)00897-3. PMID 12007577.

- Sulfiredoxin 1 (SRXN1) and Thioredoxin reductase 1 (TXNRD1) support the reduction and recovery of peroxiredoxins, proteins important in the detoxification of highly reactive peroxides, including hydrogen peroxide and peroxynitrite.

- Neumann CA, Cao J, Manevich Y (December 2009). “Peroxiredoxin 1 and its role in cell signaling” (PDF). Cell Cycle. 8 (24): 4072–8. doi:10.4161/cc.8.24.10242. PMC 7161701. PMID 19923889.

- Soriano FX, Baxter P, Murray LM, Sporn MB, Gillingwater TH, Hardingham GE (March 2009). “Transcriptional regulation of the AP-1 and Nrf2 target gene sulfiredoxin”. Molecules and Cells. 27 (3): 279–82. doi:10.1007/s10059-009-0050-y. PMC 2837916. PMID 19326073.

- Heme oxygenase-1 (HMOX1, HO-1) is an enzyme that catalyzes the breakdown of heme into the antioxidant biliverdin, the anti-inflammatory agent carbon monoxide, and iron. HO-1 is a NRF2 target gene that has been shown to protect from a variety of pathologies, including sepsis, hypertension, atherosclerosis, acute lung injury, kidney injury, and pain. In a recent study, however, induction of HO-1 has been shown to exacerbate early brain injury after intracerebral hemorrhage.

- Jarmi T, Agarwal A (February 2009). “Heme oxygenase and renal disease”. Current Hypertension Reports. 11 (1): 56–62. doi:10.1007/s11906-009-0011-z. PMID 19146802. S2CID 36932369.

- Wang J, Doré S (June 2007). “Heme oxygenase-1 exacerbates early brain injury after intracerebral haemorrhage”. Brain. 130 (Pt 6): 1643–52. doi:10.1093/brain/awm095. PMC 2291147. PMID 17525142.

- The glutathione S-transferase (GST) family includes cytosolic, mitochondrial, and microsomal enzymes that catalyze the conjugation of GSH with endogenous and xenobiotic electrophiles. After detoxification by glutathione (GSH) conjugation catalyzed by GSTs, the body can eliminate potentially harmful and toxic compounds. GSTs are induced by NRF2 activation and represent an important route of detoxification.

- Hayes JD, Chanas SA, Henderson CJ, McMahon M, Sun C, Moffat GJ, et al. (February 2000). “The Nrf2 transcription factor contributes both to the basal expression of glutathione S-transferases in mouse liver and to their induction by the chemopreventive synthetic antioxidants, butylated hydroxyanisole and ethoxyquin”. Biochemical Society Transactions. 28 (2): 33–41. doi:10.1042/bst0280033. PMID 10816095.

- The UDP-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) family catalyze the conjugation of a glucuronic acid moiety to a variety of endogenous and exogenous substances, making them more water-soluble and readily excreted. Important substrates for glucuronidation include bilirubin and acetaminophen. NRF2 has been shown to induce UGT1A1 and UGT1A6.

- Yueh MF, Tukey RH (March 2007). “Nrf2-Keap1 signaling pathway regulates human UGT1A1 expression in vitro and in transgenic UGT1 mice”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 282 (12): 8749–58. doi:10.1074/jbc.M610790200. PMID 17259171.

- Multidrug resistance-associated proteins (Mrps) are important membrane transporters that efflux various compounds from various organs and into bile or plasma, with subsequent excretion in the feces or urine, respectively. Mrps have been shown to be upregulated by NRF2 and alteration in their expression can dramatically alter the pharmacokinetics and toxicity of compounds.

- Maher JM, Dieter MZ, Aleksunes LM, Slitt AL, Guo G, Tanaka Y, et al. (November 2007). “Oxidative and electrophilic stress induces multidrug resistance-associated protein transporters via the nuclear factor-E2-related factor-2 transcriptional pathway”. Hepatology. 46 (5): 1597–610. doi:10.1002/hep.21831. PMID 17668877. S2CID 19513808.

- Reisman SA, Csanaky IL, Aleksunes LM, Klaassen CD (May 2009). “Altered disposition of acetaminophen in Nrf2-null and Keap1-knockdown mice”. Toxicological Sciences. 109 (1): 31–40. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfp047. PMC 2675638. PMID 19246624.

- Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 is also a primary target of NFE2L2. Several interesting studies have also identified this hidden circuit in NRF2 regulations. In the mouse Keap1 (INrf2) gene, Lee and colleagues found that an AREs located on a negative strand can subtly connect Nrf2 activation to Keap1 transcription. When examining NRF2 occupancies in human lymphocytes, Chorley and colleagues identified an approximately 700 bp locus within the KEAP1 promoter region was consistently top rank enriched, even at the whole-genome scale. These basic findings have depicted a mutually influenced pattern between NRF2 and KEAP1. NRF2-driven KEAP1 expression characterized in human cancer contexts, especially in human squamous cell cancers, implicated a new perspective in understanding NRF2 signaling regulation.

- Lee OH, Jain AK, Papusha V, Jaiswal AK (December 2007). “An auto-regulatory loop between stress sensors INrf2 and Nrf2 controls their cellular abundance”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 282 (50): 36412–20. doi:10.1074/jbc.M706517200. PMID 17925401.

- Chorley BN, Campbell MR, Wang X, Karaca M, Sambandan D, Bangura F, et al. (August 2012). “Identification of novel NRF2-regulated genes by ChIP-Seq: influence on retinoid X receptor alpha”. Nucleic Acids Research. 40 (15): 7416–29. doi:10.1093/nar/gks409. PMC 3424561. PMID 22581777.

- Tian Y, Liu Q, Yu S, Chu Q, Chen Y, Wu K, Wang L (October 2020). “NRF2-Driven KEAP1 Transcription in Human Lung Cancer”. Molecular Cancer Research. 18 (10): 1465–1476. doi:10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-20-0108. PMID 32571982. S2CID 219989242.

Tissue distribution

NRF2 is ubiquitously expressed with the highest concentrations (in descending order) in the kidney, muscle, lung, heart, liver, and brain.

- Moi P, Chan K, Asunis I, Cao A, Kan YW (October 1994). “Isolation of NF-E2-related factor 2 (NRF2), a NF-E2-like basic leucine zipper transcriptional activator that binds to the tandem NF-E2/AP1 repeat of the beta-globin locus control region”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 91 (21): 9926–30. Bibcode:1994PNAS…91.9926M. doi:10.1073/pnas.91.21.9926. PMC 44930. PMID 7937919

Clinical relevance

Dimethyl fumarate, marketed as Tecfidera by Biogen Idec, was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in March 2013 following the conclusion of a Phase III clinical trial which demonstrated that the drug reduced relapse rates and increased time to progression of disability in people with multiple sclerosis. The mechanism of action of dimethyl fumarate is not well understood. Dimethyl fumarate (and its metabolite, monomethyl fumarate) activates the NRF2 pathway and has been identified as a nicotinic acid receptor agonist in vitro. The label includes warnings about the risk of anaphylaxis and angioedema, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), lymphopenia, and liver damage; other adverse effects include flushing and gastrointestinal events, such as diarrhea, nausea, and upper abdominal pain.

- “Dimethyl fumarate label” (PDF). FDA. December 2017. Retrieved 19 July 2018. For label updates see FDA index page for NDA 204063

- Gold R, Kappos L, Arnold DL, Bar-Or A, Giovannoni G, Selmaj K, et al. (September 2012). “Placebo-controlled phase 3 study of oral BG-12 for relapsing multiple sclerosis”. The New England Journal of Medicine. 367 (12): 1098–107. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1114287. hdl:2078.1/124401. PMID 22992073.

The dithiolethiones are a class of organosulfur compounds, of which oltipraz, an NRF2 inducer, is most well understood. Oltipraz inhibits cancer formation in rodent organs, including the bladder, blood, colon, kidney, liver, lung, pancreas, stomach, and trachea, skin, and mammary tissue. However, clinical trials of oltipraz have not demonstrated efficacy and have shown significant side effects, including neurotoxicity and gastrointestinal toxicity. Oltipraz also generates superoxide radicals, which can be toxic.

- Zhang Y, Gordon GB (July 2004). “A strategy for cancer prevention: stimulation of the Nrf2-ARE signaling pathway”. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 3 (7): 885–93. doi:10.1158/1535-7163.885.3.7. PMID 15252150.

- Prince M, Li Y, Childers A, Itoh K, Yamamoto M, Kleiner HE (March 2009). “Comparison of citrus coumarins on carcinogen-detoxifying enzymes in Nrf2 knockout mice”. Toxicology Letters. 185 (3): 180–6. doi:10.1016/j.toxlet.2008.12.014. PMC 2676710. PMID 19150646.

- Velayutham M, Villamena FA, Fishbein JC, Zweier JL (March 2005). “Cancer chemopreventive oltipraz generates superoxide anion radical”. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 435 (1): 83–8. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2004.11.028. PMID 15680910.

Associated pathology

Genetic activation of NRF2 may promote the development of de novo cancerous tumors as well as the development of atherosclerosis by raising plasma cholesterol levels and cholesterol content in the liver. It has been suggested that the latter effect may overshadow the potential benefits of antioxidant induction afforded by NRF2 activation.

- DeNicola GM, Karreth FA, Humpton TJ, Gopinathan A, Wei C, Frese K, et al. (July 2011). “Oncogene-induced Nrf2 transcription promotes ROS detoxification and tumorigenesis”. Nature. 475 (7354): 106–9. doi:10.1038/nature10189. PMC 3404470. PMID 21734707.

- “Natural antioxidants could scupper tumour’s detox”. New Scientist (2820). July 6, 2011. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- Barajas B, Che N, Yin F, Rowshanrad A, Orozco LD, Gong KW, et al. (January 2011). “NF-E2-related factor 2 promotes atherosclerosis by effects on plasma lipoproteins and cholesterol transport that overshadow antioxidant protection”. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 31 (1): 58–66. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.210906. PMC 3037185. PMID 20947826.

- Araujo JA (2012). “Nrf2 and the promotion of atherosclerosis: lessons to be learned”. Clin. Lipidol. 7 (2): 123–126. doi:10.2217/clp.12.5. S2CID 73042634.

Interactions

NFE2L2 has been shown to interact with MAFF, MAFG, MAFK, C-jun, CREBBP, EIF2AK3, KEAP1, and UBC.

- Venugopal R, Jaiswal AK (December 1998). “Nrf2 and Nrf1 in association with Jun proteins regulate antioxidant response element-mediated expression and coordinated induction of genes encoding detoxifying enzymes”. Oncogene. 17 (24): 3145–56. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1202237. PMID 9872330.

- Katoh Y, Itoh K, Yoshida E, Miyagishi M, Fukamizu A, Yamamoto M (October 2001). “Two domains of Nrf2 cooperatively bind CBP, a CREB binding protein, and synergistically activate transcription”. Genes to Cells. 6 (10): 857–68. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2443.2001.00469.x. PMID 11683914. S2CID 22999855.

- Cullinan SB, Zhang D, Hannink M, Arvisais E, Kaufman RJ, Diehl JA (October 2003). “Nrf2 is a direct PERK substrate and effector of PERK-dependent cell survival”. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 23 (20): 7198–209. doi:10.1128/MCB.23.20.7198-7209.2003. PMC 230321. PMID 14517290.

- Guo Y, Yu S, Zhang C, Kong AN (November 2015). “Epigenetic regulation of Keap1-Nrf2 signaling”. Free Radical Biology & Medicine. 88 (Pt B): 337–349. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.06.013. PMC 4955581. PMID 26117320.

- Shibata T, Ohta T, Tong KI, Kokubu A, Odogawa R, Tsuta K, et al. (September 2008). “Cancer related mutations in NRF2 impair its recognition by Keap1-Cul3 E3 ligase and promote malignancy”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 105 (36): 13568–73. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10513568S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0806268105. PMC 2533230. PMID 18757741.

- Wang XJ, Sun Z, Chen W, Li Y, Villeneuve NF, Zhang DD (August 2008). “Activation of Nrf2 by arsenite and monomethylarsonous acid is independent of Keap1-C151: enhanced Keap1-Cul3 interaction”. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 230 (3): 383–9. doi:10.1016/j.taap.2008.03.003. PMC 2610481. PMID 18417180.

- Patel R, Maru G (June 2008). “Polymeric black tea polyphenols induce phase II enzymes via Nrf2 in mouse liver and lungs”. Free Radical Biology & Medicine. 44 (11): 1897–911. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.02.006. PMID 18358244.

See also

References

- GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000116044 – Ensembl, May 2017

- GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000015839 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ “Human PubMed Reference:”. National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ “Mouse PubMed Reference:”. National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- Moi P, Chan K, Asunis I, Cao A, Kan YW (October 1994). “Isolation of NF-E2-related factor 2 (NRF2), a NF-E2-like basic leucine zipper transcriptional activator that binds to the tandem NF-E2/AP1 repeat of the beta-globin locus control region”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 91 (21): 9926–30. Bibcode:1994PNAS…91.9926M. doi:10.1073/pnas.91.21.9926. PMC 44930. PMID 7937919

- Gold R, Kappos L, Arnold DL, Bar-Or A, Giovannoni G, Selmaj K, et al. (September 2012). “Placebo-controlled phase 3 study of oral BG-12 for relapsing multiple sclerosis”. The New England Journal of Medicine. 367 (12): 1098–107. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1114287. hdl:2078.1/124401. PMID 22992073.

- Gureev AP, Popov VN, Starkov AA (2020). “Crosstalk between the mTOR and Nrf2/ARE signaling pathways as a target in the improvement of long-term potentiation”. Experimental Gerontology. 328: 113285. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2020.113285. PMC 7145749. PMID 32165256.

- Zhu Y, Yang Q, Liu H, Chen W (2020). “Phytochemical compounds targeting on Nrf2 for chemoprevention in colorectal cancer”. European Journal of Pharmacology. 887: 173588. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2020.173588. PMID 32961170. S2CID 221863319.

- Ahmed S, Luo L, Tang X (2017). “Nrf2 signaling pathway: Pivotal roles in inflammation”. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) – Molecular Basis of Disease. 1863 (2): 585–597. doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2016.11.005. PMID 27825853.

- He F, Ru X, Wen T (January 2020). “NRF2, a Transcription Factor for Stress Response and Beyond”. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 21 (13): 4777. doi:10.3390/ijms21134777. PMC 7369905. PMID 32640524.

- Dodson M, de la Vega MR, Cholanians AB, Schmidlin CJ, Chapman E, Zhang DD (January 2019). “Modulating NRF2 in Disease: Timing Is Everything”. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology. 59: 555–575. doi:10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010818-021856. PMC 6538038. PMID 30256716.

- Calabrese EJ, Kozumbo WJ (May 2021). “The hormetic dose-response mechanism: Nrf2 activation”. Pharmacological Research. 167: 105526. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2021.105526. PMID 33667690. S2CID 232130837.

- Motohashi H, Katsuoka F, Engel JD, Yamamoto M (April 2004). “Small Maf proteins serve as transcriptional cofactors for keratinocyte differentiation in the Keap1-Nrf2 regulatory pathway”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 101 (17): 6379–84. Bibcode:2004PNAS..101.6379M. doi:10.1073/pnas.0305902101. PMC 404053. PMID 15087497.

- Motohashi H, Yamamoto M (November 2004). “Nrf2-Keap1 defines a physiologically important stress response mechanism”. Trends in Molecular Medicine. 10 (11): 549–57. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2004.09.003. PMID 15519281.

- Nioi P, Nguyen T, Sherratt PJ, Pickett CB (December 2005). “The carboxy-terminal Neh3 domain of Nrf2 is required for transcriptional activation”. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 25 (24): 10895–906. doi:10.1128/MCB.25.24.10895-10906.2005. PMC 1316965. PMID 16314513.

- McMahon M, Thomas N, Itoh K, Yamamoto M, Hayes JD (July 2004). “Redox-regulated turnover of Nrf2 is determined by at least two separate protein domains, the redox-sensitive Neh2 degron and the redox-insensitive Neh6 degron”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 279 (30): 31556–67. doi:10.1074/jbc.M403061200. PMID 15143058.

- Tonelli C, Chio II, Tuveson DA (December 2018). “Transcriptional Regulation by Nrf2”. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling. 29 (17): 1727–1745. doi:10.1089/ars.2017.7342. PMC 6208165. PMID 28899199.

- Chan JY, Cheung MC, Moi P, Chan K, Kan YW (March 1995). “Chromosomal localization of the human NF-E2 family of bZIP transcription factors by fluorescence in situ hybridization”. Human Genetics. 95 (3): 265–9. doi:10.1007/BF00225191. PMID 7868116. S2CID 23774837.

- “Entrez Gene: NFE2L2 nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2”.

- Itoh K, Wakabayashi N, Katoh Y, Ishii T, Igarashi K, Engel JD, Yamamoto M (January 1999). “Keap1 represses nuclear activation of antioxidant responsive elements by Nrf2 through binding to the amino-terminal Neh2 domain”. Genes & Development. 13 (1): 76–86. doi:10.1101/gad.13.1.76. PMC 316370. PMID 9887101.

- Kobayashi A, Kang MI, Okawa H, Ohtsuji M, Zenke Y, Chiba T, et al. (August 2004). “Oxidative stress sensor Keap1 functions as an adaptor for Cul3-based E3 ligase to regulate proteasomal degradation of Nrf2”. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 24 (16): 7130–9. doi:10.1128/MCB.24.16.7130-7139.2004. PMC 479737. PMID 15282312.

- Yamamoto T, Suzuki T, Kobayashi A, Wakabayashi J, Maher J, Motohashi H, Yamamoto M (April 2008). “Physiological significance of reactive cysteine residues of Keap1 in determining Nrf2 activity”. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 28 (8): 2758–70. doi:10.1128/MCB.01704-07. PMC 2293100. PMID 18268004.

- Sekhar KR, Rachakonda G, Freeman ML (April 2010). “Cysteine-based regulation of the CUL3 adaptor protein Keap1”. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 244 (1): 21–6. doi:10.1016/j.taap.2009.06.016. PMC 2837771. PMID 19560482.

- Itoh K, Chiba T, Takahashi S, Ishii T, Igarashi K, Katoh Y, et al. (July 1997). “An Nrf2/small Maf heterodimer mediates the induction of phase II detoxifying enzyme genes through antioxidant response elements”. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 236 (2): 313–22. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1997.6943. PMID 9240432.

- Venugopal R, Jaiswal AK (December 1996). “Nrf1 and Nrf2 positively and c-Fos and Fra1 negatively regulate the human antioxidant response element-mediated expression of NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase1 gene”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 93 (25): 14960–5. Bibcode:1996PNAS…9314960V. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.25.14960. PMC 26245. PMID 8962164.

- Solis WA, Dalton TP, Dieter MZ, Freshwater S, Harrer JM, He L, et al. (May 2002). “Glutamate-cysteine ligase modifier subunit: mouse Gclm gene structure and regulation by agents that cause oxidative stress”. Biochemical Pharmacology. 63 (9): 1739–54. doi:10.1016/S0006-2952(02)00897-3. PMID 12007577.

- Neumann CA, Cao J, Manevich Y (December 2009). “Peroxiredoxin 1 and its role in cell signaling” (PDF). Cell Cycle. 8 (24): 4072–8. doi:10.4161/cc.8.24.10242. PMC 7161701. PMID 19923889.

- Soriano FX, Baxter P, Murray LM, Sporn MB, Gillingwater TH, Hardingham GE (March 2009). “Transcriptional regulation of the AP-1 and Nrf2 target gene sulfiredoxin”. Molecules and Cells. 27 (3): 279–82. doi:10.1007/s10059-009-0050-y. PMC 2837916. PMID 19326073.

- Jarmi T, Agarwal A (February 2009). “Heme oxygenase and renal disease”. Current Hypertension Reports. 11 (1): 56–62. doi:10.1007/s11906-009-0011-z. PMID 19146802. S2CID 36932369.

- Wang J, Doré S (June 2007). “Heme oxygenase-1 exacerbates early brain injury after intracerebral haemorrhage”. Brain. 130 (Pt 6): 1643–52. doi:10.1093/brain/awm095. PMC 2291147. PMID 17525142.

- Hayes JD, Chanas SA, Henderson CJ, McMahon M, Sun C, Moffat GJ, et al. (February 2000). “The Nrf2 transcription factor contributes both to the basal expression of glutathione S-transferases in mouse liver and to their induction by the chemopreventive synthetic antioxidants, butylated hydroxyanisole and ethoxyquin”. Biochemical Society Transactions. 28 (2): 33–41. doi:10.1042/bst0280033. PMID 10816095.

- Yueh MF, Tukey RH (March 2007). “Nrf2-Keap1 signaling pathway regulates human UGT1A1 expression in vitro and in transgenic UGT1 mice”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 282 (12): 8749–58. doi:10.1074/jbc.M610790200. PMID 17259171.

- Maher JM, Dieter MZ, Aleksunes LM, Slitt AL, Guo G, Tanaka Y, et al. (November 2007). “Oxidative and electrophilic stress induces multidrug resistance-associated protein transporters via the nuclear factor-E2-related factor-2 transcriptional pathway”. Hepatology. 46 (5): 1597–610. doi:10.1002/hep.21831. PMID 17668877. S2CID 19513808.

- Reisman SA, Csanaky IL, Aleksunes LM, Klaassen CD (May 2009). “Altered disposition of acetaminophen in Nrf2-null and Keap1-knockdown mice”. Toxicological Sciences. 109 (1): 31–40. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfp047. PMC 2675638. PMID 19246624.

- Lee OH, Jain AK, Papusha V, Jaiswal AK (December 2007). “An auto-regulatory loop between stress sensors INrf2 and Nrf2 controls their cellular abundance”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 282 (50): 36412–20. doi:10.1074/jbc.M706517200. PMID 17925401.

- Chorley BN, Campbell MR, Wang X, Karaca M, Sambandan D, Bangura F, et al. (August 2012). “Identification of novel NRF2-regulated genes by ChIP-Seq: influence on retinoid X receptor alpha”. Nucleic Acids Research. 40 (15): 7416–29. doi:10.1093/nar/gks409. PMC 3424561. PMID 22581777.

- Tian Y, Liu Q, Yu S, Chu Q, Chen Y, Wu K, Wang L (October 2020). “NRF2-Driven KEAP1 Transcription in Human Lung Cancer”. Molecular Cancer Research. 18 (10): 1465–1476. doi:10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-20-0108. PMID 32571982. S2CID 219989242.

- “Dimethyl fumarate label” (PDF). FDA. December 2017. Retrieved 19 July 2018. For label updates see FDA index page for NDA 204063

- Prince M, Li Y, Childers A, Itoh K, Yamamoto M, Kleiner HE (March 2009). “Comparison of citrus coumarins on carcinogen-detoxifying enzymes in Nrf2 knockout mice”. Toxicology Letters. 185 (3): 180–6. doi:10.1016/j.toxlet.2008.12.014. PMC 2676710. PMID 19150646.

- Zhang Y, Gordon GB (July 2004). “A strategy for cancer prevention: stimulation of the Nrf2-ARE signaling pathway”. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 3 (7): 885–93. doi:10.1158/1535-7163.885.3.7. PMID 15252150.

- Velayutham M, Villamena FA, Fishbein JC, Zweier JL (March 2005). “Cancer chemopreventive oltipraz generates superoxide anion radical”. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 435 (1): 83–8. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2004.11.028. PMID 15680910.

- DeNicola GM, Karreth FA, Humpton TJ, Gopinathan A, Wei C, Frese K, et al. (July 2011). “Oncogene-induced Nrf2 transcription promotes ROS detoxification and tumorigenesis”. Nature. 475 (7354): 106–9. doi:10.1038/nature10189. PMC 3404470. PMID 21734707.

- “Natural antioxidants could scupper tumour’s detox”. New Scientist (2820). July 6, 2011. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- Barajas B, Che N, Yin F, Rowshanrad A, Orozco LD, Gong KW, et al. (January 2011). “NF-E2-related factor 2 promotes atherosclerosis by effects on plasma lipoproteins and cholesterol transport that overshadow antioxidant protection”. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 31 (1): 58–66. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.210906. PMC 3037185. PMID 20947826.

- Araujo JA (2012). “Nrf2 and the promotion of atherosclerosis: lessons to be learned”. Clin. Lipidol. 7 (2): 123–126. doi:10.2217/clp.12.5. S2CID 73042634.

- Venugopal R, Jaiswal AK (December 1998). “Nrf2 and Nrf1 in association with Jun proteins regulate antioxidant response element-mediated expression and coordinated induction of genes encoding detoxifying enzymes”. Oncogene. 17 (24): 3145–56. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1202237. PMID 9872330.

- Katoh Y, Itoh K, Yoshida E, Miyagishi M, Fukamizu A, Yamamoto M (October 2001). “Two domains of Nrf2 cooperatively bind CBP, a CREB binding protein, and synergistically activate transcription”. Genes to Cells. 6 (10): 857–68. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2443.2001.00469.x. PMID 11683914. S2CID 22999855.

- Cullinan SB, Zhang D, Hannink M, Arvisais E, Kaufman RJ, Diehl JA (October 2003). “Nrf2 is a direct PERK substrate and effector of PERK-dependent cell survival”. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 23 (20): 7198–209. doi:10.1128/MCB.23.20.7198-7209.2003. PMC 230321. PMID 14517290.

- Guo Y, Yu S, Zhang C, Kong AN (November 2015). “Epigenetic regulation of Keap1-Nrf2 signaling”. Free Radical Biology & Medicine. 88 (Pt B): 337–349. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.06.013. PMC 4955581. PMID 26117320.

- Shibata T, Ohta T, Tong KI, Kokubu A, Odogawa R, Tsuta K, et al. (September 2008). “Cancer related mutations in NRF2 impair its recognition by Keap1-Cul3 E3 ligase and promote malignancy”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 105 (36): 13568–73. Bibcode:2008PNAS..10513568S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0806268105. PMC 2533230. PMID 18757741.

- Wang XJ, Sun Z, Chen W, Li Y, Villeneuve NF, Zhang DD (August 2008). “Activation of Nrf2 by arsenite and monomethylarsonous acid is independent of Keap1-C151: enhanced Keap1-Cul3 interaction”. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 230 (3): 383–9. doi:10.1016/j.taap.2008.03.003. PMC 2610481. PMID 18417180.

- Patel R, Maru G (June 2008). “Polymeric black tea polyphenols induce phase II enzymes via Nrf2 in mouse liver and lungs”. Free Radical Biology & Medicine. 44 (11): 1897–911. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.02.006. PMID 18358244.

External links

- NFE2L2+protein,+human at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

This article incorporates text from the United States National Library of Medicine, which is in the public domain.

Leave a Reply