Armour & Company (bad blood featuring Factor VIII product Factorate, Revlon, Stevie Nicks’ papa, poison soap, poison baby powder, a ghost town in Missouri involving CDC, EPA and the Crisco Kid, Hexachlorophene and something called 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin) and some other bullshit

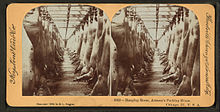

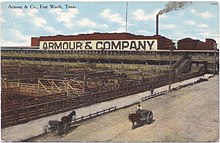

Armour & Company was an American company and was one of the five leading firms in the meat packing industry. It was founded in Chicago, in 1867, by the Armour brothers led by Philip Danforth Armour. By 1880, the company had become Chicago’s most important business and had helped make Chicago and its Union Stock Yards the center of America’s meatpacking industry. During the same period, its facility in Omaha, Nebraska, boomed, making the city’s meatpacking industry the largest in the nation by 1959. In connection with its meatpacking operations, the company also ventured into pharmaceuticals (Armour Pharmaceuticals) and soap manufacturing, introducing Dial soap in 1948.

Presently, the Armour food brands are split between Smithfield Foods (for refrigerated meat — “Armour Meats”) and ConAgra Brands (for canned shelf-stable meat products — “Armour Star”). The Armour pharmaceutical brand is owned by Forest Laboratories. Dial soap is now owned by Henkel.

History

1863–1970

Armour and Company had its roots in Milwaukee, where in 1863 Philip D. Armour joined with John Plankinton (the founder of the Layton and Plankinton Packing Company in 1852) to establish Plankinton, Armour and Company. Together, the partners expanded Plankinton’s Milwaukee meat packing operation and established branches in Chicago and Kansas City and an exporting house in New York City. Armour and Plankinton dissolved their partnership in 1884 with the Milwaukee operation eventually becoming the Cudahy Packing Company.

- “Plankinton, John 1820 – 1891”. Archived from the original on 2013-10-30. Retrieved 2014-02-11.

In addition to meats, Armour sold many types of consumer products made from animals in its early years, including glue, oil, fertilizer, hairbrushes, buttons, oleomargarine, and drugs, made from slaughterhouse byproducts. Armour operated in an environment without labor unions, health inspections, or government regulation. Accidents were commonplace. Armour was notorious for the low pay it offered its line workers. It fought unionization by banning known union activists and breaking strikes in 1904 and 1921 by employing African Americans and new immigrants as strikebreakers. The company did not become fully unionized until the late 1930s when the meatpacking union succeeded in creating an interracial industrial union as part of the Congress of Industrial Organizations.

During the Spanish–American War (1898), Armour sold 500,000 pounds (230,000 kg) of beef to the US Army. An army inspector tested the meat two months later and found that 751 cases were rotten and had contributed to the food poisoning of thousands of soldiers.

- Zinn, Howard. A People’s History of the United States. New York: Perennial, 2003. p.309 ISBN 0-06-052837-0

In the first decade of the 20th century, a young Dale Carnegie, representing the South Omaha sales region, became the company’s highest-selling salesman, an experience he drew on in his best-selling book, How to Win Friends and Influence People.

- How To Win Friends And Influence People, by Dale Carnegie, Introduction by Lowell Thomas, p. 9, Copyright 1964

In the early 1920s, Armour encountered financial troubles and the family sold its majority interest to financier Frederick H. Prince. The firm retained its position as one of the largest American firms through the Great Depression and the sharp increase in demand during World War II. During this period, it expanded its operations across the United States; at its peak, the company employed just under 50,000 people.

In 1948, Armour, which had made soap for years as a byproduct of the meatpacking process, developed a deodorant soap by adding the germicidal agent AT-7 to soap. This limited body odor by reducing bacteria on the skin. The new soap was named Dial because of its 24-hour protection against the odor-causing bacteria. Armour introduced the soap with a full-page advertisement using scented ink in the Chicago Tribune. During the 1950s, Dial became the best-selling deodorant soap in the US. The company adopted the slogan “Aren’t you glad you use Dial? Don’t you wish everybody did?” in 1953. In the 1960s, the Dial brand was expanded to include deodorants and shaving creams. Because of the popularity and strong sales of Dial brand, fueled by magazine, radio, and television advertising, Armour’s consumer-products business was incorporated as Armour-Dial, Inc. in 1967.

In 1958, William Wood-Prince, a cousin of Frederick H. Prince, became president of Armour and Company.

The formula for Dial soap was modified to remove AT-7 (hexachlorophene?) after the FDA ended over-the-counter availability in 1972.

- “The Milwaukee Sentinel: “US Order Curbs Hexachlorophene” (UPI), September 23, 1972. From Google News”. Archived from the original on April 2, 2016. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

AT7

Hexachlorophene, also known as Nabac, is an organochlorine compound that was once widely used as a disinfectant. The compound occurs as a white odorless solid, although commercial samples can be off-white and possess a slightly phenolic odor. It is insoluble in water but dissolves in acetone, ethanol, diethyl ether, and chloroform. In medicine, hexachlorophene is useful as a topical anti-infective and anti-bacterial agent. It is also used in agriculture as a soil fungicide, plantbactericide, and acaricide. Hexachlorophene is produced by alkylation of 2,4,5-trichlorophenol with formaldehyde. Related antiseptics are prepared similarly, e.g., bromochlorophene and dichlorophene. Trade names for hexachlorophene include: Acigena, Almederm, AT7 (dial soap), AT17, Bilevon, Exofene, Fostril, Gamophen, G-11, Germa-Medica, Hexosan, K-34, Septisol, Surofene, M3.

- Fiege H, Voges HM, Hamamoto T, Umemura S, Iwata T, Miki H, et al. (2000). “Phenol Derivatives”. Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a19_313. ISBN 3-527-30673-0.

- “Hexachlorophene”. PharmGKB. Retrieved 2012-12-28.

- Dept. of Health, Education, and Welfare (1972). “Consumer news”. Office of Consumer Affairs. 2 (21): 10.

The LD50 (oral, rat) is 59 mg/kg, indicating that the compound is relatively toxic. It is not mutagenic nor teratogenic according to Ullmann’s Encyclopedia, but “embryotoxic and produces some teratogenic effects” according to the International Agency for Research on Cancer.2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzodioxin (TCDD) is always a contaminant in this compound’s production. Several accidents releasing many kilograms of TCDD have been reported. The reaction between 2,4,5-trichlorophenol and formaldehyde is exothermic. If the reaction occurs without adequate cooling, TCDD is produced in significant quantities as a byproduct and contaminant. The Seveso disaster and the Times Beach, Missouri, contamination incident exemplify the industrial hazards of hexachlorophene production.(now a ghost town.) In Times Beach, Missouri, several hundred people were poisoned by extremely high concentrations of TCDD by Russell Martin Bliss, who sprayed TCDD-contaminated waste oil on dusty roads to avoid large dust clouds. Bliss himself obtained the waste oil from NEPACCO, a company that produced Agent Orange. No one was ever charged in relation to the incident, and the city of Times Beach was abandoned and disincorporated following an investigation by the CDC and EPA. This is marked as the single largest contamination of a civilian area by TCDD in United States history.) contamination incident exemplify the industrial hazards of hexachlorophene production.

- Fiege H, Voges HM, Hamamoto T, Umemura S, Iwata T, Miki H, et al. (2000). “Phenol Derivatives”. Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a19_313. ISBN 3-527-30673-0.

- “Hexachlorophene”. International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) – Summaries & Evaluations. IPCS Inchem. 20: 241. 1998 [1979].

- 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) is a polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxin (sometimes shortened, though inaccurately, to simply ‘dioxin’) with the chemical formula C12H4Cl4O2. Pure TCDD is a colorless solid with no distinguishable odor at room temperature. It is usually formed as an unwanted product in burning processes of organic materials or as a side product in organic synthesis. TCDD is the most potent compound (congener) of its series (polychlorinated dibenzodioxins, known as PCDDs or simply dioxins) and became known as a contaminant in Agent Orange, a herbicide used in the Vietnam War. TCDD was released into the environment in the Seveso disaster. It is a persistent organic pollutant.

- Tuomisto, Jouko (2019) Dioxins and dioxin-like compounds: toxicity in humans and animals, sources, and behaviour in the environment. WikiJournal of Medicine 6(1): 8 | https://doi.org/10.15347/wjm/2019.008

- Schecter A, Birnbaum L, Ryan JJ, Constable JD (2006). “Dioxins: an overview”. Environ. Res. 101 (3): 419–28. Bibcode:2006ER….101..419S. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2005.12.003. PMID 16445906.

- M.H. Sweeney; P. Mocarelli (2000). “Human health effects after exposure to 2,3,7,8- TCDD”. Food Addit. Contam. 17 (4): 303–316. doi:10.1080/026520300283379. PMID 10912244. S2CID 11814994.

- TCDD and dioxin-like compounds act via a specific receptor present in all cells: the aryl hydrocarbon (AH) receptor. This receptor is a transcription factor which is involved in the expression of genes; it has been shown that high doses of TCDD either increase or decrease the expression of several hundred genes in rats. Genes of enzymes activating the breakdown of foreign and often toxic compounds are classic examples of such genes (enzyme induction). TCDD increases the enzymes breaking down, e.g., carcinogenic polycyclic hydrocarbons such as benzo(a)pyrene.

- L. Poellinger (2000). “Mechanistic aspects—the dioxin (aryl hydrocarbon) receptor”. Food Additives and Contaminants. 17 (4): 261–6. doi:10.1080/026520300283333. PMID 10912240. S2CID 22295283.

- Mandal PK (May 2005). “Dioxin: a review of its environmental effects and its aryl hydrocarbon receptor biology”. J. Comp. Physiol. B. 175 (4): 221–30. doi:10.1007/s00360-005-0483-3. PMID 15900503. S2CID 20508397.

- J. Lindén; S. Lensu; J. Tuomisto; R. Pohjanvirta. (2010). “Dioxins, the aryl hydrocarbon receptor and the central regulation of energy balance. A review”. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology. 31 (4): 452–478. doi:10.1016/j.yfrne.2010.07.002. PMID 20624415. S2CID 34036181.

- Tijet N, Boutros PC, Moffat ID, et al. (2006). “Hydrocarbon receptor regulates distinct dioxin-dependent and dioxin-independent gene batteries”. Molecular Pharmacology. 69 (1): 140–153. doi:10.1124/mol.105.018705. PMID 16214954. S2CID 1913812.

- Okey AB (July 2007). “An aryl hydrocarbon receptor odyssey to the shores of toxicology: the Deichmann Lecture, International Congress of Toxicology-XI”. Toxicol. Sci. 98 (1): 5–38. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfm096. PMID 17569696.

- These polycyclic hydrocarbons also activate the AH receptor, but less than TCDD and only temporarily. Even many natural compounds present in vegetables cause some activation of the AH receptor. This phenomenon can be viewed as adaptive and beneficial, because it protects the organism from toxic and carcinogenic substances. Excessive and persistent stimulation of AH receptor, however, leads to a multitude of adverse effects.[10]

- Okey AB (July 2007). “An aryl hydrocarbon receptor odyssey to the shores of toxicology: the Deichmann Lecture, International Congress of Toxicology-XI”. Toxicol. Sci. 98 (1): 5–38. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfm096. PMID 17569696.

- Mandlekar S, Hong JL, Kong AN (August 2006). “Modulation of metabolic enzymes by dietary phytochemicals: a review of mechanisms underlying beneficial versus unfavorable effects”. Curr. Drug Metab. 7 (6): 661–75. doi:10.2174/138920006778017795. PMID 16918318.

- DeGroot, Danica; He, Guochun; Fraccalvieri, Domenico; Bonati, Laura; Pandini, Allesandro; Denison, Michael S. (2011). “AHR Ligands: Promiscuity in Binding and Diversity in Response”. The AH Receptor in Biology and Toxicology. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. pp. 63–79. doi:10.1002/9781118140574.ch4. ISBN 9781118140574.

- The physiological function of the AH receptor has been the subject of continuous research. One obvious function is to increase the activity of enzymes breaking down foreign chemicals or normal chemicals of the body as needed. There seem to be many other functions, however, related to the development of various organs and the immune systems or other regulatory functions. The AH receptor is phylogenetically highly conserved, with a history of at least 600 million years, and is found in all vertebrates. Its ancient analogs are important regulatory proteins even in more primitive species. In fact, knock-out animals with no AH receptor are prone to illness and developmental problems. Taken together, this implies the necessity of a basal degree of AH receptor activation to achieve normal physiological function.

- J. Lindén; S. Lensu; J. Tuomisto; R. Pohjanvirta. (2010). “Dioxins, the aryl hydrocarbon receptor and the central regulation of energy balance. A review”. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology. 31 (4): 452–478. doi:10.1016/j.yfrne.2010.07.002. PMID 20624415. S2CID 34036181.

- Rothhammer, V; Quintana, FJ (March 2019). “The aryl hydrocarbon receptor: an environmental sensor integrating immune responses in health and disease”. Nature Reviews. Immunology. 19 (3): 184–197. doi:10.1038/s41577-019-0125-8. PMID 30718831. S2CID 59603271.

- TCDD has never been produced commercially except as a pure chemical for scientific research. It is, however, formed as a synthesis side product when producing certain chlorophenols or chlorophenoxy acid herbicides. It may also be formed along with other polychlorinated dibenzodioxins and dibenzofuranes in any burning of hydrocarbons where chlorine is present, especially if certain metal catalysts such as copper are also present. Usually a mixture of dioxin-like compounds is produced, therefore a more thorough treatise is under dioxins and dioxin-like compounds. The greatest production occurs from waste incineration, metal production, and fossil-fuel and wood combustion. Dioxin production can usually be reduced by increasing the combustion temperature. Total U.S. emissions of PCCD/Fs were reduced from ca. 14 kg TEq in 1987 to 1.4 kg TEq in 2000.

- Saracci, R.; Kogevinas, M.; Winkelmann, R.; Bertazzi, P. A.; Bueno De Mesquita, B. H.; Coggon, D.; Green, L. M.; Kauppinen, T.; l’Abbé, K. A.; Littorin, M.; Lynge, E.; Mathews, J. D.; Neuberger, M.; Osman, J.; Pearce, N. (1991). “Cancer mortality in workers exposed to chlorophenoxy herbicides and chlorophenols”. The Lancet. 338 (8774): 1027–1032. doi:10.1016/0140-6736(91)91898-5. PMID 1681353. S2CID 23115128.

- Harnly, M.; Stephens, R.; McLaughlin, C.; Marcotte, J.; Petreas, M.; Goldman, L. (1995). “Polychlorinated Dibenzo-p-dioxin and Dibenzofuran Contamination at Metal Recovery Facilities, Open Burn Sites, and a Railroad Car Incineration Facility”. Environmental Science & Technology. 29 (3): 677–684. Bibcode:1995EnST…29..677H. doi:10.1021/es00003a015. PMID 22200276.

- DHHS: Report on Carcinogens, Twelfth Edition (2011) Archived 17 February 2013 at the Wayback Machine (accessed 2013-08-01)

- Jouko Tuomisto &al.: Synopsis on Dioxins and PCBs Archived 27 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine (accessed 2013-08-01), p.40; using data from EPA‘s National Center for Environmental Assessment

- Tuomisto, Jouko (2019) Dioxins and dioxin-like compounds: toxicity in humans and animals, sources, and behaviour in the environment. WikiJournal of Medicine 6(1): 8 | https://doi.org/10.15347/wjm/2019.008

- There have been numerous incidents where people have been exposed to high doses of TCDD.

- In 1976, thousands of inhabitants of Seveso, Italy were exposed to TCDD after an accidental release of several kilograms of TCDD from a pressure tank. Many animals died, and high concentrations of TCDD, up to 56,000 pg/g of fat, were noted especially in children playing outside and eating local food. The acute effects were limited to about 200 cases of chloracne. Long-term effects seem to include a slight excess of multiple myeloma and myeloid leukaemia, as well as some developmental effects such as disturbed development of teeth and excess of girls born to fathers who were exposed as children. Several other long-term effects have been suspected, but the evidence is not very strong.

- Angela Cecilia Pesatori; Dario Consonni; Maurizia Rubagotti; Paolo Grillo; Pier Alberto Bertazzi (2009). “Cancer incidence in the population exposed to dioxin after the “Seveso accident”: twenty years of follow-up”. Environmental Health. 8 (1): 39. Bibcode:2009EnvHe…8…39P. doi:10.1186/1476-069X-8-39. PMC 2754980. PMID 19754930.

- S. Alaluusua; et al. (2004). “Developmental dental aberrations after the dioxin accident in Seveso”. Environ. Health Perspect. 112 (13): 1313–1318. doi:10.1289/ehp.6920. PMC 1247522. PMID 15345345.

- P. Mocarelli; et al. (1991). “Serum concentrations of 2,3,7,8- tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin and test results from selected residents of Seveso, Italy”. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health. 32 (4): 357–366. doi:10.1080/15287399109531490. PMID 1826746.

- P. Mocarelli; et al. (2000). “Paternal concentrations of dioxin and sex ratio of offspring” (PDF). Lancet. 355 (9218): 1858–1863. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02290-X. hdl:10281/16136. PMID 10866441. S2CID 6353869.

- M.H. Sweeney; P. Mocarelli (2000). “Human health effects after exposure to 2,3,7,8- TCDD”. Food Addit. Contam. 17 (4): 303–316. doi:10.1080/026520300283379. PMID 10912244. S2CID 11814994.

- In Times Beach, Missouri, several hundred people were poisoned by extremely high concentrations of TCDD by Russell Martin Bliss, who sprayed TCDD-contaminated waste oil on dusty roads to avoid large dust clouds. Bliss himself obtained the waste oil from NEPACCO, a company that produced Agent Orange. No one was ever charged in relation to the incident, and the city of Times Beach was abandoned and disincorporated following an investigation by the CDC and EPA. This is marked as the single largest contamination of a civilian area by TCDD in United States history.

- In Vienna, two women were poisoned at their workplace in 1997, and the measured concentrations in one of them were the highest ever measured in a human being, 144,000 pg/g of fat. This is about 100,000 times the concentrations in most people today and about 10,000 times the sum of all dioxin-like compounds in young people today. They survived but suffered from difficult chloracne for several years. The poisoning likely happened in October 1997 but was not discovered until April 1998. At the institute where the women worked as secretaries, high concentrations of TCDD were found in one of the labs, suggesting that the compound had been produced there. The police investigation failed to find clear evidence of crime, and no one was ever prosecuted. Aside from malaise and amenorrhea there were few other symptoms or abnormal laboratory findings.

- A. Geusau; K. Abraham; K. Geissler; M.O. Sator; G. Stingl; E. Tschachler (2001). “Severe 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) intoxication: clinical and laboratory effects”. Environ. Health Perspect. 109 (8): 865–869. doi:10.1289/ehp.01109865. PMC 1240417. PMID 11564625.

- In 2004, presidential candidate Viktor Yushchenko of Ukraine was poisoned with a large dose of TCDD. His blood TCDD concentration was measured 108,000 pg/g of fat, which is the second highest ever measured. This concentration implies a dose exceeding 2 mg, or 25 μg/kg of body weight. He suffered from chloracne for many years, but after initial malaise, other symptoms or abnormal laboratory findings were few.

- Sorg, O.; Zennegg, M.; Schmid, P.; Fedosyuk, R.; Valikhnovskyi, R.; Gaide, O.; Kniazevych, V.; Saurat, J.-H. (2009). “2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) poisoning in Victor Yushchenko: identification and measurement of TCDD metabolites”. The Lancet. 374 (9696): 1179–1185. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60912-0. PMID 19660807. S2CID 24761553.

- An area of polluted land in Italy, known as the Triangle of Death, is contaminated with TCDD from years of illegal waste disposal by organized crime.

- Senior, K; Mazza, A (September 2004). “Italian “Triangle of death” linked to waste crisis”. Lancet Oncol. 5 (9): 525–527. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(04)01561-x. PMID 15384216.

- “Il triangolo della morte”. rassegna.it. March 2007. Archived from the original on 15 February 2009. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- “Discariche piene di rifiuti tossici quello è il triangolo della morte”. la Repubblica. 31 August 2004.

- In 1976, thousands of inhabitants of Seveso, Italy were exposed to TCDD after an accidental release of several kilograms of TCDD from a pressure tank. Many animals died, and high concentrations of TCDD, up to 56,000 pg/g of fat, were noted especially in children playing outside and eating local food. The acute effects were limited to about 200 cases of chloracne. Long-term effects seem to include a slight excess of multiple myeloma and myeloid leukaemia, as well as some developmental effects such as disturbed development of teeth and excess of girls born to fathers who were exposed as children. Several other long-term effects have been suspected, but the evidence is not very strong.

Selective removal of hexachlorophene from market – France

In 1972, the “Bébé” brand of baby powder in France killed 39 babies. It also did great damage to the central nervous systems of several hundred other babies. The batch of toxic “Bébé” brand of powder was mistakenly manufactured with 6% hexachlorophene. This industrial accident directly led to the removal of hexachlorophene from consumer products worldwide.

- Talcum Suspected in Deaths of 21 French Babies”. No. 29 August 1972. New York Times. p. 10. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- “FDA CURBS USE OF GERMICIDE TIED TO INFANT DESTHS”. No. 23 September 1972. New York Times. p. 1. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

Selective removal of hexachlorophene from market – United States

In 1972, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) halted production and distribution of products containing more than 1% of hexachlorophene. After that change, most products containing hexachlorophene were available only with a doctor’s prescription. The restrictions were enacted after 15 deaths in the United States, and the 39 deaths in France mentioned above, were reported following brain damage caused by hexachlorophene.

- Germicide Limit Stirs Confusion, New York Times, September 24, 1972, pg. 53.

- “The Milwaukee Sentinel: “US Order Curbs Hexachlorophene” (UPI), September 23, 1972. From Google News”. Archived from the original on April 2, 2016. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- Ocala Star Banner, “15 Deaths Cited In Use of Germ Killer, Hexachlorophene” (AP), March 21, 1973. From Google News.

Several companies manufactured over-the-counter preparations which utilised hexachlorophene in their formulations. One product, Baby Magic Bath by The Mennen Company, was recalled in 1971, and removed from retail distribution.

Two commercial preparations using hexachlorophene, pHisoDerm and pHisoHex, were widely used as antibacterial skin cleansers in the treatment of acne, (with pHisoDerm developed for those allergic to the active ingredients in pHisoHex). During the 1960s, both were available over the counter in the US. After the ban, pHisoDerm was reformulated without hexachlorophene, and continued to be sold over-the-counter, while pHisoHex, (which contained 3% hexachlorophene – 3 times the legal limit imposed in 1972), became available as a prescription body wash. In the European Community countries during the 1970s and 1980s, pHisoHex remained available over the counter. A related product, pHisoAc, was used as a skin mask to dry and peel away acne lesions whilst pHiso-Scrub, a hexachlorophene-impregnated sponge for scrubbing, has since been discontinued. Several substitute products (including triclosan) were developed, but none had the germ-killing capability of hexachlorophene. (Sanofi-Aventis became the sole European manufacturer of pHisoHex, while The Mentholatum Company owns the pHisoDerm brand today. Sanofi-Aventis discontinued production of several forms of pHisoHex in August 2009 and discontinued all production of pHisoHex in September 2013).

- Ocala Star Banner, “15 Deaths Cited In Use of Germ Killer, Hexachlorophene” (AP), March 21, 1973. From Google News.

- “Drug Shortages”. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 10 September 2014.

Bristol-Myers’ discontinued Ipana toothpaste brand at one time contained hexachlorophene.

- “1959 Ipana Toothpaste Ad”. YouTube.

Selective removal of hexachlorophene from market – Germany

In Germany, cosmetics containing hexachlorophene have been banned since 1985.

Selective removal of hexachlorophene from market – Austria

In Austria, the sale of drugs containing the substance has been banned since 1990.

Armour 1970–1985

In 1970, Armour and Company was acquired by Chicago-based bus company Greyhound Corporation after a hostile takeover attempt by General Host Corporation a year before. Prior to the hostile takeover bid by General Host, the company had originally planned to merge with Gulf and Western Industries in 1968.

- Lueck, Thomas J. (June 11, 1983). “Greyhound to Dispose of Armour”. The New York Times. Retrieved 2014-07-07.

- Belair, Felix Jr. (18 January 1973). “SEC sues General Host and 9 over Armour bid”. The New York Times. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

In 1971, Greyhound relocated Armour’s headquarters from Chicago to Phoenix, Arizona, to a new $83-million building. Rock icon Stevie Nicks‘ father, Jess Nicks, who was a Greyhound executive, became president of Armour.

In 1978, Greyhound sold Armour Pharmaceuticals to Revlon. Revlon sold its drug unit in 1985 to Rorer (later known as Rhône-Poulenc Rorer). Forest Laboratories acquired the rights to Armour Thyroid from Rhone-Poulenc Rorer in 1991. The remaining assets of Armour Pharmaceuticals are now part of CSL Behring.

- “Revlon Set to Buy Armour Druz Units”. The New York Times. 6 July 1977.

- Crudele, John (30 November 1985). “RORER BUYS DRUG UNIT OF REVLON”. The New York Times.

- “COMPANY NEWS; Rhone Sells Rights”. The New York Times. Reuters. 3 January 1991.

- “Caliber Associates – Clients”. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2013-09-09

Armour’s Factor VIII product “Factorate” was widely reported as infecting thousands of hemophiliacs worldwide with HIV during the 1980s; there have also been allegations that the firm suppressed evidence showing the product was defective.As a result, there have been lawsuits, inquiries and criminal charges.

- Society, Eric Feldman Associate Director New York University’s Institute for Law and; Health, Columbia University Ronald Bayer Professor Joseph L. Mailman School of Public (5 March 1999). Blood Feuds : AIDS, Blood, and the Politics of Medical Disaster: AIDS, Blood, and the Politics of Medical Disaster. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 9780199759736.

- “New Scientist”. Reed Business Information. 17 July 1986.

- “Firm squelched study showing risk of HIV in hemophilia drug”. AIDS Policy & Law. 10 (19): 5. 20 October 1995. PMID 11362848.

This makes no sense to my brain so I will have to read more as I am inclined. In the meantime, I came across a Factor 8 website run by a nonprofit in UK which attempts to explain how this happened all over the world. Still not making good sense to my brain but taking a few notes anyway:

Armour / Revlon

- History of ArmourArmour & Company begins in our story being owned by Greyhound Lines which is most notably known for its Coach / Bus services in the USA. However during 1977/1978 it was sold to Revlon, yes, that company you might suspect has only ever made beauty products , actually has connections to Factor VIII.

- Armour’s Factor VIII product – Factorate Revlon had a good run with Armour and their main-stay Factor VIII product, which was aptly named “Factorate”.

- What happened to Armour? Revlon remained in control of Armour from 1978 until around 1987 (Their attempts to sell the company began in the mid -1980’s, shortly after Haemophiliacs began to become aware they were infected with HIV). Revlon sold Armour to a company called Rorer Pharmaceutical for almost $700 Million. Rorer went on to merge with Rhône-Poulenc in 1990.

- More about Armour The Krever Commission, an Inquiry into blood product contamination in Canada concluded that Armour had suppressed research showing that its heat-treating process did not effectively kill HIV. In 1996 Armour was merged with German company Behringwerke, the new alliance was named “Centeon”. It was 3 years later in 1999 that the entity known as Centeon changed its name to Aventis Behring following a merger of the parent companies, Rorer and Hoechst AG, which merged to become known as Aventis. Sometime in 2004, an Australian-rooted company called CSL acquired Aventis Behring for almost 1 Billion Dollars. The organisation today is known as CSL Behring.

- FACTOR 8 – INDEPENDENT HAEMOPHILIA GROUP website

Baxter / Travenol / Hyland

- History of BaxterIn 1949 Baxter created Travenol Laboratories, a pharmaceutical arm of the company and it also acquired Hyland Laboratories in 1952, both of which would go on to be involved in the Factor business.

- Baxter’s Factor VIII product – Hemofil Baxter manufactured and sold a Factor VIII product called Hemofil.

- What happened to Baxter? In 1996 Baxter acquired a former competitor in the business, Immuno AG, for in the region of $715,000,000. In 2015 Baxter “spun-off” it’s Haemophilia treatment business into a new company called Baxalta and this was shortly followed by a mega sell-off in 2016 to Shire PLC for some $32 Billion.

- FACTOR 8 – INDEPENDENT HAEMOPHILIA GROUP website

Bayer / Cutter / Miles

- History of BayerFactor VIII manufacturer Cutter Laboratories was original owned by Miles, both of which would eventually be taken over by Bayer. In 1974 Bayer acquired Cutter Laboratories and 4 years later in 1978 they acquired Miles Labs.

- Bayer’s Factor VIII product – Koate Bayer manufactured and sold a Factor VIII product called Koate. It also manufactured and sold a Factor IX product called Konyne.

- What happened to Bayer? In 1995 a raft of legal action was underway by those harmed by Factor VIII products in the United States and it was around this time that Bayer dropped the “Miles” name as a brand. A company called Talecris was established in 2005 by Cerberus Capital Management and Ampersand, which bought out Bayer’s plasma business and assets for 590 Million Dollars, however, it is important to note that Bayer retained it’s recombinant Factor VIII “Kogenate” product which was not included in the sale and Bayer remain active in the Haemophilia treatment market to this day. 5 Years after taking over Aventis Behring, CSL attempted to buy-out Talecris in 2009 for in the region of $3.1 billion, The deal however was cut down by the FTC who deemed the situation illegal. It would turn out to be Spanish pharmaceutical company Grifols who would ultimately land the deal, and in 2011, a year after announcing the $3.4 Billion Dollar takeover, Grifols completed its acquisition of Talecris.

- FACTOR 8 – INDEPENDENT HAEMOPHILIA GROUP website

BPL / Blood Products Laboratory

- History of BPLThe BPL (Blood Products Laboratory) was and still is based in Elstree, UK and was the site at which the majority of “home-made” Factor VIII was made. Today BPL has changed it’s name slightly to stand for Bio-Products Laboratory.

- BPL’s Factor VIII products – BPL’s Factor VIII batch numbers during the 1970s and 1980s typically began with “HL”, “HLA” or “HLB”. It is unclear what the abbreviations stood for.

- What happened to BPL? It was in 1950 that BPL first began in the business of processing human plasma and was established by the Medical Research Council (MRC) as part of the Lister Institute. In 2013 the Department of Health sold 80% of it’s stake in BPL to an investment company called Bain Capital for approximately £230 Million.In 2016 it was completely sold off to a commercial company based in China called the Creat Group for £820 Million.

- FACTOR 8 – INDEPENDENT HAEMOPHILIA GROUP website

Immuno

- History of Immuno – Immuno AG was a pharmaceutical company founded in 1960 by scientists Dr. Otto Schwarz and Dr. Hans Eibl. With headquarters in Vienna, Austria Immuno AG sold its products around the globe.

- Immuno’s Factor VIII product – KryobulinImmuno AG manufactured a Factor VIII blood product called Kryobulin. Some Kryobulin was made from volunteer austrian plasma donors, and some was made from paid donors in the US.

- What happened to Immuno – Healthcare giant Baxter purchased Immuno AG in 1996 for some $715 million.

- FACTOR 8 – INDEPENDENT HAEMOPHILIA GROUP website

Greyhound’s rapid diversification and frequent unit restructurings led to erratic profitability. In 1981, John W. Teets was appointed chairman of Greyhound and began selling unprofitable subsidiaries. After meat packers struck at the Armour plants in the early-1980s, Teets shut 29 facilities and sold Armour Food Company to ConAgra in 1983 but kept the Armour Star canned meat business. Armour-Dial continued to manufacture the canned meat products using the Armour Star trademark under license from ConAgra.

- Hollie, Pamel (30 June 1983). “Greyhound Selling Armour”. The New York Times. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

Armour 1985–2000

In 1985, Greyhound acquired the household products business of Purex Industries, Inc. in 1985 and combined it with Armour-Dial to form The Dial Corporation.

- Hicks, Jonathan (22 February 1985). “Greyhound to buy Purex Division”. The New York Times. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

In late 1995, parent company Greyhound (renamed The Dial Corp in 1991) announced its intention to spin off the Dial consumer-products business. Afterwards, Dial’s former parent company was renamed Viad Corp, consisting of the service businesses. The Dial consumer business was reborn as the new Dial Corporation, relocating its corporate offices to Scottsdale, Arizona, adjacent to its long-time research and development facility. Under new CEO Malcolm Jozoff, a former P&G executive, the new Dial Corporation underwent major layoffs in the fall of 1996 and a series of financially disastrous acquisitions the following four years. In 2000, Jozoff was replaced by Herbert Baum with a mandate from the board of directors to find a suitable buyer for the company.

- Winter, Greg (9 August 2000). “2 officers resign as Dial says profits will be off”. The New York Times. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

Armour 2000–present

Dial was acquired by Henkel KGaA of Düsseldorf, Germany in March 2004. The food business of Dial, including Armour Star canned meats, was sold to Pinnacle Foods in March 2006. In 2007 Pinnacle Foods was acquired by the Blackstone Group, a New York City-based private equity firm. Conagra acquired Pinnacle Foods for $10.9 billion in 2018.

- Pinnacle Foods Group acquires Armour dry food products”. Food Ingredients First. 2 March 2006. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- “Blackstone Group buying Pinnacle Foods”. NBC News. 12 February 2007. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- Watrous, Monica (December 21, 2018). “Conagra Brands cleaning up Pinnacle Foods’ mess”. Food Business News. Retrieved August 22, 2022.

- Naidu, Richa. “Conagra to buy Pinnacle for $8.1 billion, creating frozen food powerhouse”. Reuters U.S. Retrieved 2018-07-14.

In July 2006, ConAgra sold most of their refrigerated meats businesses, including the Armour brand, to Smithfield Foods.

- “ConAgra Foods to Sell Refrigerated Meats Businesses to Smithfield Foods for $575 Million; Sale Includes Butterball, Eckrich and Armour Brands”. Business Wire. 31 July 2006. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

See also

- Treet

- Armour Refrigerator Line

- Desiccated thyroid extract (Armour Thyroid) dear god

- Lester Pearson, former Canadian Prime Minister of Nobel winner worked at Armour meat plant in Chicago.

References

- “Plankinton, John 1820 – 1891”. Archived from the original on 2013-10-30. Retrieved 2014-02-11.

- Zinn, Howard. A People’s History of the United States. New York: Perennial, 2003. p.309 ISBN 0-06-052837-0

- How To Win Friends And Influence People, by Dale Carnegie, Introduction by Lowell Thomas, p. 9, Copyright 1964

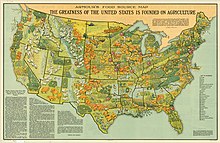

- Armour Company, and Armour Company, Chicago. Armour’s Food Source Map : The Greatness of the United States Is Founded on Agriculture. Chicago: Armour & Company, 1922. https://collections.lib.uwm.edu/digital/collection/agdm/id/1967

- Lueck, Thomas J. (June 11, 1983). “Greyhound to Dispose of Armour”. The New York Times. Retrieved 2014-07-07.

- Belair, Felix Jr. (18 January 1973). “SEC sues General Host and 9 over Armour bid”. The New York Times. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- “Revlon Set to Buy Armour Druz Units”. The New York Times. 6 July 1977.

- Crudele, John (30 November 1985). “RORER BUYS DRUG UNIT OF REVLON”. The New York Times.

- “COMPANY NEWS; Rhone Sells Rights”. The New York Times. Reuters. 3 January 1991.

- “Caliber Associates – Clients”. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2013-09-09.

- Society, Eric Feldman Associate Director New York University’s Institute for Law and; Health, Columbia University Ronald Bayer Professor Joseph L. Mailman School of Public (5 March 1999). Blood Feuds : AIDS, Blood, and the Politics of Medical Disaster: AIDS, Blood, and the Politics of Medical Disaster. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 9780199759736.

- “New Scientist”. Reed Business Information. 17 July 1986.

- “Firm squelched study showing risk of HIV in hemophilia drug”. AIDS Policy & Law. 10 (19): 5. 20 October 1995. PMID 11362848.

- Hollie, Pamel (30 June 1983). “Greyhound Selling Armour”. The New York Times. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

- Hicks, Jonathan (22 February 1985). “Greyhound to buy Purex Division”. The New York Times. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

- Winter, Greg (9 August 2000). “2 officers resign as Dial says profits will be off”. The New York Times. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- Pinnacle Foods Group acquires Armour dry food products”. Food Ingredients First. 2 March 2006. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- “Blackstone Group buying Pinnacle Foods”. NBC News. 12 February 2007. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- Watrous, Monica (December 21, 2018). “Conagra Brands cleaning up Pinnacle Foods’ mess”. Food Business News. Retrieved August 22, 2022.

- Naidu, Richa. “Conagra to buy Pinnacle for $8.1 billion, creating frozen food powerhouse”. Reuters U.S. Retrieved 2018-07-14.

- “ConAgra Foods to Sell Refrigerated Meats Businesses to Smithfield Foods for $575 Million; Sale Includes Butterball, Eckrich and Armour Brands”. Business Wire. 31 July 2006. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/peace/1957/pearson/biographical/

- Fiege H, Voges HM, Hamamoto T, Umemura S, Iwata T, Miki H, et al. (2000). “Phenol Derivatives”. Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a19_313. ISBN 3-527-30673-0.

- “Hexachlorophene”. International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) – Summaries & Evaluations. IPCS Inchem. 20: 241. 1998 [1979].

- “Talcum Suspected in Deaths of 21 French Babies”. No. 29 August 1972. New York Times. p. 10. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- “FDA CURBS USE OF GERMICIDE TIED TO INFANT DESTHS”. No. 23 September 1972. New York Times. p. 1. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- Germicide Limit Stirs Confusion, New York Times, September 24, 1972, pg. 53.

- “The Milwaukee Sentinel: “US Order Curbs Hexachlorophene” (UPI), September 23, 1972. From Google News”. Archived from the original on April 2, 2016. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- Ocala Star Banner, “15 Deaths Cited In Use of Germ Killer, Hexachlorophene” (AP), March 21, 1973. From Google News.

- “Drug Shortages”. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 10 September 2014.

- “1959 Ipana Toothpaste Ad”. YouTube.

- Rechtsinformationssystem des österreichischen Bundeskanzleramtes (in German)

- “Hexachlorophene”. PharmGKB. Retrieved 2012-12-28.

- Dept. of Health, Education, and Welfare (1972). “Consumer news”. Office of Consumer Affairs. 2 (21): 10.

- NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. “#0594”. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- Shiu WY; et al. (1988). “Physical-chemical properties of chlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins”. Environ Sci Technol. 22 (6): 651–658. Bibcode:1988EnST…22..651S. doi:10.1021/es00171a006. S2CID 53459209.

- Tuomisto, Jouko (2019) Dioxins and dioxin-like compounds: toxicity in humans and animals, sources, and behaviour in the environment. WikiJournal of Medicine 6(1): 8 | https://doi.org/10.15347/wjm/2019.008

- Schecter A, Birnbaum L, Ryan JJ, Constable JD (2006). “Dioxins: an overview”. Environ. Res. 101 (3): 419–28. Bibcode:2006ER….101..419S. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2005.12.003. PMID 16445906.

- M.H. Sweeney; P. Mocarelli (2000). “Human health effects after exposure to 2,3,7,8- TCDD”. Food Addit. Contam. 17 (4): 303–316. doi:10.1080/026520300283379. PMID 10912244. S2CID 11814994.

- L. Poellinger (2000). “Mechanistic aspects—the dioxin (aryl hydrocarbon) receptor”. Food Additives and Contaminants. 17 (4): 261–6. doi:10.1080/026520300283333. PMID 10912240. S2CID 22295283.

- Mandal PK (May 2005). “Dioxin: a review of its environmental effects and its aryl hydrocarbon receptor biology”. J. Comp. Physiol. B. 175 (4): 221–30. doi:10.1007/s00360-005-0483-3. PMID 15900503. S2CID 20508397.

- J. Lindén; S. Lensu; J. Tuomisto; R. Pohjanvirta. (2010). “Dioxins, the aryl hydrocarbon receptor and the central regulation of energy balance. A review”. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology. 31 (4): 452–478. doi:10.1016/j.yfrne.2010.07.002. PMID 20624415. S2CID 34036181.

- Tijet N, Boutros PC, Moffat ID, et al. (2006). “Hydrocarbon receptor regulates distinct dioxin-dependent and dioxin-independent gene batteries”. Molecular Pharmacology. 69 (1): 140–153. doi:10.1124/mol.105.018705. PMID 16214954. S2CID 1913812.

- Okey AB (July 2007). “An aryl hydrocarbon receptor odyssey to the shores of toxicology: the Deichmann Lecture, International Congress of Toxicology-XI”. Toxicol. Sci. 98 (1): 5–38. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfm096. PMID 17569696.

- Mandlekar S, Hong JL, Kong AN (August 2006). “Modulation of metabolic enzymes by dietary phytochemicals: a review of mechanisms underlying beneficial versus unfavorable effects”. Curr. Drug Metab. 7 (6): 661–75. doi:10.2174/138920006778017795. PMID 16918318.

- DeGroot, Danica; He, Guochun; Fraccalvieri, Domenico; Bonati, Laura; Pandini, Allesandro; Denison, Michael S. (2011). “AHR Ligands: Promiscuity in Binding and Diversity in Response”. The AH Receptor in Biology and Toxicology. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. pp. 63–79. doi:10.1002/9781118140574.ch4. ISBN 9781118140574.

- Rothhammer, V; Quintana, FJ (March 2019). “The aryl hydrocarbon receptor: an environmental sensor integrating immune responses in health and disease”. Nature Reviews. Immunology. 19 (3): 184–197. doi:10.1038/s41577-019-0125-8. PMID 30718831. S2CID 59603271.

- “Consultation on assessment of the health risk of dioxins: re-evaluation of the tolerable daily intake (TDI): Executive summary”. Food Additives & Contaminants. 17 (4): 223–240. 2000. doi:10.1080/713810655. PMID 10912238. S2CID 216644694.

- Ngo, Anh D; Taylor, Richard; Roberts, Christine L; Nguyen, Tuan V (2006). “Association between Agent Orange and birth defects: Systematic review and meta-analysis”. International Journal of Epidemiology. 35 (5): 1220–1230. doi:10.1093/ije/dyl038. PMID 16543362.

- Y.P. Dragan; D. Schrenk (2000). “Animal studies addressing the carcinogenicity of TCDD (or related compounds) with an emphasis on tumour promotion”. Food Additives and Contaminants. 17 (4): 289–302. doi:10.1080/026520300283360. PMID 10912243. S2CID 24500449.

- M. Viluksela; et al. (2000). “Liver tumor-promoting activity of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) in TCDD-sensitive and TCDD resistant rat strains”. Cancer Res. 60 (24): 6911–20. PMID 11156390.

- Knerr S, Schrenk D (October 2006). “Carcinogenicity of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin in experimental models”. Mol Nutr Food Res. 50 (10): 897–907. doi:10.1002/mnfr.200600006. PMID 16977593.

- Angela Cecilia Pesatori; Dario Consonni; Maurizia Rubagotti; Paolo Grillo; Pier Alberto Bertazzi (2009). “Cancer incidence in the population exposed to dioxin after the “Seveso accident”: twenty years of follow-up”. Environmental Health. 8 (1): 39. Bibcode:2009EnvHe…8…39P. doi:10.1186/1476-069X-8-39. PMC 2754980. PMID 19754930.

- International Agency for Research on Cancer (1997). Polychlorinated dibenzo-para-dioxins and polychlorinated dibenzofurans. Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Vol. 69. Lyon: IARC. ISBN 978-92-832-1269-0.

- IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risk to Humans (2012). 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzopara-dioxin, 2,3,4,7,8-pentachlorodibenzofuran, and 3,3′,4,4′,5-pentachlorobiphenyl. Vol. 100F. International Agency for Research on Cancer. pp. 339–378.

- Kogevinas M, Becher H, Benn T, Bertazzi PA, Boffetta P, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Coggon D, Colin D, Flesch-Janys D, Fingerhut M, Green L, Kauppinen T, Littorin M, Lynge E, Mathews JD, Neuberger M, Pearce N, Saracci R (1997). “Cancer mortality in workers exposed to phenoxy herbicides, chlorophenols, and dioxins”. Am J Epidemiol. 145 (12): 1061–1075. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009069. PMID 9199536.

- Schwarz M, Appel KE (October 2005). “Carcinogenic risks of dioxin: mechanistic considerations”. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 43 (1): 19–34. doi:10.1016/j.yrtph.2005.05.008. PMID 16054739.

- Cole P, Trichopoulos D, Pastides H, Starr T, Mandel JS (December 2003). “Dioxin and cancer: a critical review”. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 38 (3): 378–88. doi:10.1016/j.yrtph.2003.08.002. PMID 14623487.

- Walker NJ, Wyde ME, Fischer LJ, Nyska A, Bucher JR (October 2006). “Comparison of chronic toxicity and carcinogenicity of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) in 2-year bioassays in female Sprague-Dawley rats”. Mol Nutr Food Res. 50 (10): 934–944. doi:10.1002/mnfr.200600031. PMC 1934421. PMID 16977594.

- Boffetta P, Mundt KA, Adami HO, Cole P, Mandel JS (August 2011). “TCDD and cancer: a critical review of epidemiologic studies”. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 41 (7): 622–636. doi:10.3109/10408444.2011.560141. PMC 3154583. PMID 21718216.

- Buffler PA, Ginevan ME, Mandel JS, Watkins DK (September 2011). “The Air Force health study: an epidemiologic retrospective”. Ann Epidemiol. 21 (9): 673–687. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2011.02.001. PMID 21441038.

- Warner, M; Mocarelli, P; Samuels, S; Needham, L; Brambilla, P; Eskenazi, B (December 2011). “Dioxin exposure and cancer risk in the Seveso Women’s Health Study”. Environmental Health Perspectives. 119 (12): 1700–1705. doi:10.1289/ehp.1103720. PMC 3261987. PMID 21810551.

- J.T. Tuomisto; J. Pekkanen; H. Kiviranta; E. Tukiainen; T. Vartiainen; J. Tuomisto (2004). “Soft-tissue sarcoma and dioxin: a case-control study”. Int. J. Cancer. 108 (6): 893–900. doi:10.1002/ijc.11635. PMID 14712494.

- Tuomisto, J.; et al. (2005). “Dioxin cancer risk –example of hormesis?”. Dose-Response. 3 (3): 332–341. doi:10.2203/dose-response.003.03.004. PMC 2475943. PMID 18648613.

- Malisch R, Kotz A (2014). “Dioxins and PCBs in feed and food–review from European perspective”. The Science of the Total Environment. 491–492: 2–10. Bibcode:2014ScTEn.491….2M. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.03.022. PMID 24804623.

- Rice, Glenn. “EPA’s Reanalysis of Key Issues Related to Dioxin Toxicity and Response to NAS Comments (External Review Draft)”. cfpub.epa.gov. US EPA National Center for Environmental Assessment,Cincinnati Oh. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- “Health Effects”. The Aspen Institute. August 2011. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- “Toxic Substances Portal” (PDF).

- A. Poland; J.C. Knutson (1982). “2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin and related halogenated aromatic hydrocarbons: examination of the mechanism of toxicity”. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 22 (1): 517–554. doi:10.1146/annurev.pa.22.040182.002505. PMID 6282188.

- R. Pohjanvirta; J. Tuomisto (1994). “Short-term toxicity of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzop-dioxin in laboratory animals: effects, mechanisms, and animal models”. Pharmacol. Rev. 46 (4): 483–549. PMID 7899475.

- L.S. Birnbaum; J. Tuomisto (2000). “Non-carcinogenic effects of TCDD in animals”. Food Addit. Contam. 17 (4): 275–288. doi:10.1080/026520300283351. PMID 10912242. S2CID 45117354.

- T.A. Mably; D.L. Bjerke; R.W. Moore; A. Gendron-Fitzpatrick; R.E. Peterson (1992). “In utero and lactational exposure of male rats to 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-pdioxin. 3. Effects on spermatogenesis and reproductive capability”. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 114 (1): 118–126. doi:10.1016/0041-008X(92)90103-Y. PMID 1585364.

- L.E. Gray; J.S. Ostby; W.R. Kelce (1997). “A dose-response analysis of the reproductive effects of a single gestational dose of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin in male Long Evans Hooded rat offspring”. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 146 (1): 11–20. doi:10.1006/taap.1997.8223. PMID 9299592.

- H. Kattainen; et al. (2001). “In utero/lactational 2,3,7,8- tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin exposure impairs molar tooth development in rats”. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 174 (3): 216–224. doi:10.1006/taap.2001.9216. PMID 11485382.

- S. Alaluusua; et al. (2004). “Developmental dental aberrations after the dioxin accident in Seveso”. Environ. Health Perspect. 112 (13): 1313–1318. doi:10.1289/ehp.6920. PMC 1247522. PMID 15345345.

- S. Alaluusua; P.L. Lukinmaa; J. Torppa; J. Tuomisto; T. Vartiainen (1999). “Developing teeth as biomarker of dioxin exposure”. Lancet. 353 (9148): 206. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)77214-7. PMID 9923879. S2CID 31562457.

- R.J. Kociba; et al. (1978). “Results of a two-year chronic toxicity and oncogenicity study of 2,3,7,8- tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin in rats”. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 46 (2): 279–303. doi:10.1016/0041-008X(78)90075-3. PMID 734660.

- Pitot III, H. C.; Dragan, Y. P. (2001). “Chemical carcinogenesis”. In Klaassen, C. D. (ed.). Casarett & Doull’s Toxicology: the basic science of poisons (6th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 201–267. ISBN 978-0-07-134721-1.

- Saracci, R.; Kogevinas, M.; Winkelmann, R.; Bertazzi, P. A.; Bueno De Mesquita, B. H.; Coggon, D.; Green, L. M.; Kauppinen, T.; l’Abbé, K. A.; Littorin, M.; Lynge, E.; Mathews, J. D.; Neuberger, M.; Osman, J.; Pearce, N. (1991). “Cancer mortality in workers exposed to chlorophenoxy herbicides and chlorophenols”. The Lancet. 338 (8774): 1027–1032. doi:10.1016/0140-6736(91)91898-5. PMID 1681353. S2CID 23115128.

- Harnly, M.; Stephens, R.; McLaughlin, C.; Marcotte, J.; Petreas, M.; Goldman, L. (1995). “Polychlorinated Dibenzo-p-dioxin and Dibenzofuran Contamination at Metal Recovery Facilities, Open Burn Sites, and a Railroad Car Incineration Facility”. Environmental Science & Technology. 29 (3): 677–684. Bibcode:1995EnST…29..677H. doi:10.1021/es00003a015. PMID 22200276.

- DHHS: Report on Carcinogens, Twelfth Edition (2011) Archived 17 February 2013 at the Wayback Machine (accessed 2013-08-01)

- Jouko Tuomisto &al.: Synopsis on Dioxins and PCBs Archived 27 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine (accessed 2013-08-01), p.40; using data from EPA‘s National Center for Environmental Assessment

- P. Mocarelli; et al. (1991). “Serum concentrations of 2,3,7,8- tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin and test results from selected residents of Seveso, Italy”. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health. 32 (4): 357–366. doi:10.1080/15287399109531490. PMID 1826746.

- P. Mocarelli; et al. (2000). “Paternal concentrations of dioxin and sex ratio of offspring” (PDF). Lancet. 355 (9218): 1858–1863. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02290-X. hdl:10281/16136. PMID 10866441. S2CID 6353869.

- A. Geusau; K. Abraham; K. Geissler; M.O. Sator; G. Stingl; E. Tschachler (2001). “Severe 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) intoxication: clinical and laboratory effects”. Environ. Health Perspect. 109 (8): 865–869. doi:10.1289/ehp.01109865. PMC 1240417. PMID 11564625.

- Sorg, O.; Zennegg, M.; Schmid, P.; Fedosyuk, R.; Valikhnovskyi, R.; Gaide, O.; Kniazevych, V.; Saurat, J.-H. (2009). “2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) poisoning in Victor Yushchenko: identification and measurement of TCDD metabolites”. The Lancet. 374 (9696): 1179–1185. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60912-0. PMID 19660807. S2CID 24761553.

- Senior, K; Mazza, A (September 2004). “Italian “Triangle of death” linked to waste crisis”. Lancet Oncol. 5 (9): 525–527. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(04)01561-x. PMID 15384216.

- “Il triangolo della morte”. rassegna.it. March 2007. Archived from the original on 15 February 2009. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- “Discariche piene di rifiuti tossici quello è il triangolo della morte”. la Repubblica. 31 August 2004.

- Powell, William (December 3, 2012). “Remember Times Beach: The Dioxin Disaster, 30 Years Later”. St. Louis Magazine. Retrieved April 4, 2017.

- Hinckley, Jim (2012). The Route 66 Encyclopedia. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Voyageur Press. pp. 253–254. ISBN 9780760340417.

- Environmental Protection Agency. “Times Beach Deleted from National Priorities List”. EPA Cleanup News (6): 1–3. 2001. Retrieved April 4, 2017.

- Leistner, Marilyn (1995). “The Times Beach Story”. Synthesis/Regeneration. Retrieved April 4, 2017.

- O’Neil, Tim (December 5, 2010). “A Look Back: Times Beach disappeared after 1982 flood”. St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Retrieved April 4, 2017.

- Casey Bukro (February 27, 1992). “As Town is Razed, Some Think Danger Wasn’t Real”. Chicago Tribune.

- Ashcroft, John (1985), Executive Order 85-9 (PDF), Jefferson City, Missouri: State of Missouri, retrieved April 4, 2017

- “Engineering Disasters” Modern Marvels, History Channel, Viewed March 4, 2010

- Hernan, Robert (2010). This Borrowed Earth: Lessons from the 15 Worst Environmental Disasters around the World. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9780230619838.

- Hites, Ronald (2011). “Dioxins: An Overview and History”. Environmental Science and Technology. 45 (1): 16–20. doi:10.1021/es1013664. PMID 20815379.

- Gough, Michael (1986). Dioxin, Agent Orange: The Facts. New York: Plenum Press. ISBN 0306422476.

- Sun, Marjorie (1983). “Missouri’s Costly Dioxin Lesson”. Science. 219 (4583): 367–369. Bibcode:1983Sci…219..367S. doi:10.1126/science.6849139. PMID 6849139.

- Allen, Robert (2004). Dioxin War: Truth and Lies About a Perfect Poison. London: Pluto Press.

- Suskind, Raymond (1984). “Chloracne, “the hallmark of dioxin intoxication””. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health. 11 (3): 165–171. doi:10.5271/sjweh.2240. PMID 2930898.

- Wildavsky, Aaron (1995). But Is It True? A Citizen’s Guide to Environmental Health and Safety Issues. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674089227.

- “Dioxins and their effects on human health”. World Health Organization. Retrieved December 17, 2014.

- “Missouri Legends: Ill-Fated Times Beach”. Legends of America. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- Dubuc, Carroll; Evans, William (1988). “United States v. Northeastern Pharmaceutical and Chemical Co., Inc.: The Eighth Circuit unleashes a CERCLA Dragnet on Corporate Officials”. Tort and Insurance Law Journal. 24 (1): 168–178.

- Moore, Kenneth; Kowalski, Kathiann (1984). “When is One Generator Liable for Another’s Waste”. Cleveland State Law Reviews. 33 (1).

- McMahon, Tom; Moertl, Katie (1988). “The Erosion of Traditional Corporate Law Doctrines in Environmental Cases”. Natural Resources & Environment. 3 (3).

- Hernan,Robert Emmet This Borrowed Earth, Chapter “Times Beach”, Palgrave 2010, ISBN 978-0-230-61983-8

- Route 66 State Park in Eureka Cleared by EPA Officials by Julie Brown Patton Eureka-Wildwood Patch 20 Nov 2012

- Lieberman, Adam; Kwon, Simona (2004). “Facts versus Fears: A Review of the Greatest Unfounded Health Scares of Recent Times”. American Council on Science and Health.

- Eskenazi, Brenda; Mocarelli, Paolo; Warner, Marcella; Needham, Larry; Patterson, Donald G. Jr.; Samuels, Steven; Turner, Wayman; Gerthoux, Pier Mario; Brambilla, Paolo (January 2004). “Relationship of Serum TCDD Concentrations and Age at Exposure of Female Residents of Seveso, Italy”. Environmental Health Perspectives. 112 (1): 22–7. doi:10.1289/ehp.6573. PMC 1241792. PMID 14698926.

- “Top 10 Environmental Disasters”.

- B. De Marchi; S. Funtowicz; J. Ravetz. “4 Seveso: A paradoxical classic disaster”. United Nations University.

- Homberger, E.; Reggiani, G.; Sambeth, J.; Wipf, H. K. (1979). “The Seveso Accident: Its Nature, Extent and Consequences”. Ann. Occup. Hyg. Pergamon Press. 22 (4): 327–370. doi:10.1093/annhyg/22.4.327. PMID 161954.

- Kletz, Trevor (1998). What Went Wrong? Case Histories of Process Plant Disasters. Gulf. ISBN 0-88415-920-5.

- Kletz, Trevor A. (2001). Learning from Accidents (3 ed.). Oxford U.K.: Gulf Professional. pp. 103–109 (Chapter 9). ISBN 978-0-7506-4883-7.

- “Seveso – 30 Years After, A Chronology of Events”. Roche Group.

- Eskenazi, Brenda; Warner, Marcella; Brambilla, Paolo; Signorini, Stefano; Ames, Jennifer; Mocarelli, Paolo (2018-12-01). “The Seveso accident: A look at 40 years of health research and beyond”. Environment International. 121 (Pt 1): 71–84. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2018.08.051. ISSN 0160-4120. PMC 6221983. PMID 30179766.

- Milnes, M. H. (6 August 1971). “Formation of 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzodioxin by Thermal Decomposition of Sodium 2,4,5-Trichlorophenate”. Nature. Nature Publishing Group. 232 (5310): 395–396. Bibcode:1971Natur.232..395M. doi:10.1038/232395a0. PMID 16063057. S2CID 4215351.

- Hay, Alastair (18 October 1979). “Séveso: the crucial question of reactor safety”. Nature. Nature Publishing Group. 281 (5732): 521. Bibcode:1979Natur.281..521H. doi:10.1038/281521a0. S2CID 38191411.

- Eskenazi, Brenda; Mocarelli, Paolo; Warner, Marcella; Samuels, Steven; Vercellini, Paolo; Olive, David; Needham, Larry; Patterson, Donald; Brambilla, Paolo (2000-05-01). “Seveso Women’s Health Study: a study of the effects of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin on reproductive health”. Chemosphere. 40 (9): 1247–1253. Bibcode:2000Chmsp..40.1247E. doi:10.1016/S0045-6535(99)00376-8. ISSN 0045-6535. PMID 10739069.

- Assennato, G; Cervino, D; Emmett, EA; Longo, G; Merlo, F (January 1, 1989). “Follow-up of subjects who developed chloracne following TCDD exposure at Seveso”. American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 16 (2): 119–125. doi:10.1002/ajim.4700160203. PMID 2773943 – via Wiley.

- Roche Group (January 1997). “Seveso 20 years after” (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on November 17, 2023. Retrieved November 17, 2023.

- Bertazzi, Pier Alberto (1991). “Long-term effects of chemical disasters. Lessons and results from Seveso”. The Science of the Total Environment. 106 (1–2): 5–20. Bibcode:1991ScTEn.106….5B. doi:10.1016/0048-9697(91)90016-8. PMID 1835132.

- Pesatori, A.; Consonni, D.; Rubagotti, M.; Grillo, P.; Bertazzi, P. (2009). “Cancer incidence in the population exposed to dioxin after the “Seveso accident”: twenty years of follow-up”. Environmental Health. 8 (1): 39. Bibcode:2009EnvHe…8…39P. doi:10.1186/1476-069X-8-39. PMC 2754980. PMID 19754930.Free full-text

- Baccarelli, Andrea; Giacomini, Sara M.; Corbetta, Carlo; Landi, Maria Teresa; Bonzini, Matteo; Consonni, Dario; Grillo, Paolo; Jr, Donald G. Patterson; Pesatori, Angela C.; Bertazzi, Pier Alberto (2008-07-29). “Neonatal Thyroid Function in Seveso 25 Years after Maternal Exposure to Dioxin”. PLOS Medicine. 5 (7): e161. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0050161. ISSN 1549-1676. PMC 2488197. PMID 18666825.

- “Out for the count: Why levels of sperm in men are falling”. The Independent. 25 April 2010.

- Robbe, F (2016). “Seveso 1976. Oltre la diossina”. Itaca. pp. 119–120.

- B. De Marchi; S. Funtowicz; J. Ravetz. “Conclusion: “Seveso” – A paradoxical symbol”. United Nations University.

- “Original Seveso Directive 82/501/EEC (“Seveso I”)” (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-05-10.

- “Vietnam Agent Orange Campaign – Background”. Archived from the original on 2006-08-21.

- Gambit (2005), German Wikipedia page. https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gambit_(2005), accessed (in German) on December 28, 2019.

- Gambit (August 2005), Sabine Gisiger, Swiss Films Review. https://www.swissfilms.ch/en/film_search/filmdetails/-/id_film/-1704568495

- “Ich war absolut dumm”. Die Tageszeitung: Taz (in German). 2006-07-10. p. 4.

- “Original Italian lyrics with English translation”. Song Meanings. June 2019.

Further reading

- Arnould, Richard J. “Changing patterns of concentration in American meat packing, 1880–1963.” Business History Review 45.1 (1971): 18-34.

- Gras, N.S.B. and Henrietta M. Larson. Casebook in American business history (1939) pp 623–43.

- Warren, Wilson J. Tied to the great packing machine: The Midwest and meatpacking (University of Iowa Press, 2007).

External links

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Armour and Company.

- Armour Meats (Smithfield)

- Armour Star (Conagra)

| Meatpacking Industry in Omaha |

|---|

| Antiseptics and disinfectants (D08) |

|---|

| Agents used in chemical warfare incapacitation riot control |

|---|

| Municipalities and communities of St. Louis County, Missouri, United States |

|---|

- 1867 establishments in Illinois

- American companies established in 1867

- Conagra Brands brands

- Defunct companies based in Chicago

- Defunct companies based in Nebraska

- History of Chicago

- Meat packing companies based in Omaha, Nebraska

- Pinnacle Foods brands

- Shaving cream brands

- American companies disestablished in 1983

- Armour family

- Teratogens

- Chloroarenes

- Antiseptics

- Phenols

- Dibenzodioxins

- IARC Group 1 carcinogens

- Blood agents

- Environment of Missouri

- Environmental disaster ghost towns

- Former cities in Missouri

- Ghost towns in Missouri

- Ghost towns on U.S. Route 66

- Superfund sites in Missouri

- Waste disposal incidents in the United States

- 1925 establishments in Missouri

- 1985 disestablishments in Missouri

- Chemical disasters

- 1976 industrial disasters

- 1976 in Italy

- Environmental disasters in Europe

- Health disasters in Italy

- Corporate crime

- Waste disposal incidents

Leave a Reply