p-Phenylenediamine (PPD) is a derivative of aniline used in kevlar, hair dye and henna substitutions among other things, the derivatives of which are used in antiozonants among other horrors

p-Phenylenediamine (PPD) is an organic compound with the formula C6H4(NH2)2. This derivative of aniline is a white solid, but samples can darken due to air oxidation.It is mainly used as a component of engineering polymers and composites like kevlar. It is also an ingredient in hair dyes and is occasionally used as a substitute for henna.

- Merck Index, 11th Edition, 7256

Production

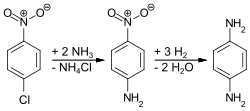

PPD is produced via three routes. Most commonly, 4-nitrochlorobenzene is treated with ammonia and the resulting 4-nitroaniline is then hydrogenated:

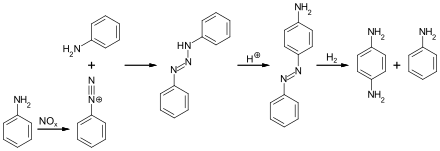

In the DuPont route, aniline is converted to diphenyltriazine, which is then converted by acid-catalysis to 4-aminoazobenzene. Hydrogenation of the latter affords PPD.

- Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry (1 ed.). Wiley. 2003-03-11. doi:10.1002/14356007.a19_405. ISBN 978-3-527-30385-4.

4-Nitroaniline, p-nitroaniline or 1-amino-4-nitrobenzene is an organic compound with the formula C6H6N2O2. A yellow solid, it is one of three isomers of nitroaniline. It is an intermediate in the production of dyes, antioxidants, pharmaceuticals, gasoline, gum inhibitors, poultry medicines, and as a corrosion inhibitor. 4-Nitroaniline is produced industrially via the amination of 4-nitrochlorobenzene:

- Booth, Gerald (2003-03-11). “Nitro Compounds, Aromatic”. In Wiley-VCH (ed.). Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry (1 ed.). Wiley. doi:10.1002/14356007.a17_411. ISBN 978-3-527-30385-4.]

ClC6H4NO2 + 2 NH3 → H2NC6H4NO2 + NH4Cl

Below is a laboratory synthesis of 4-nitroaniline from aniline. The key step in this reaction sequence is an electrophilic aromatic substitution to install the nitro group para to the amino group. The amino group can be easily protonated and become a meta director. Therefore, a protection of the acetyl group is required. After this reaction, a separation must be performed to remove 2-nitroaniline, which is also formed in a small amount during the reaction.

- Mohrig, J.R.; Morrill, T.C.; Hammond, C.N.; Neckers, D.C. (1997). “Synthesis 5: Synthesis of the Dye Para Red from Aniline”. Experimental Organic Chemistry. New York, NY: Freeman. pp. 456–467. Archived from the original on 2020-09-15. Retrieved 2007-07-18.

Applications

4-Nitroaniline is mainly consumed industrially as a precursor to p-phenylenediamine, an important dye component. The reduction is effected using iron metal and by catalytic hydrogenation.

- Booth, Gerald (2003-03-11). “Nitro Compounds, Aromatic”. In Wiley-VCH (ed.). Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry (1 ed.). Wiley. doi:10.1002/14356007.a17_411. ISBN 978-3-527-30385-4.]

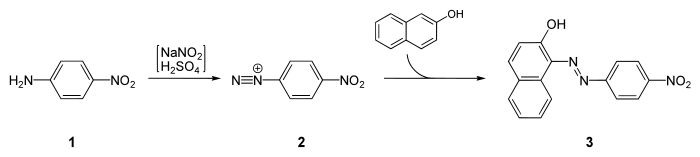

It is a starting material for the synthesis of Para Red, the first azo dye:

- Williamson, Kenneth L. (2002). Macroscale and Microscale Organic Experiments, Fourth Edition. Houghton-Mifflin. ISBN 0-618-19702-8.

Laboratory use

Nitroaniline undergoes diazotization, which allows access to 1,4-dinitrobenzene and nitrophenylarsonic acid. With phosgene, it converts to 4-nitrophenylisocyanate.

- Starkey, E. B. (1939). “p-DINITROBENZENE”. Organic Syntheses. 19: 40. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.019.0040.

- “p-NITROPHENYLARSONIC ACID”. Organic Syntheses. 26: 60. 1946. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.026.0060.

- Shriner, R. L.; Horne, W. H.; Cox, R. F. B. (1934). “p-NITROPHENYL ISOCYANATE”. Organic Syntheses. 14: 72. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.014.0072.

- “2,6-DIIODO-p-NITROANILINE”. Organic Syntheses. 12: 28. 1932. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.012.0028.

Carbon snake demonstration

When heated with sulfuric acid, it dehydrates and polymerizes explosively into a rigid foam.

- Poshkus, A. C.; Parker, J. A. (1970). “Studies on nitroaniline–sulfuric acid compositions: Aphrogenic pyrostats”. Journal of Applied Polymer Science. 14 (8): 2049–2064. doi:10.1002/app.1970.070140813.

In Carbon snake demo, paranitroaniline can be used instead of sugar, if the experiment is allowed to proceed under an obligatory fumehood. With this method the reaction phase prior to the black snake’s appearance is longer, but once complete, the black snake itself rises from the container very rapidly. This reaction may cause an explosion if too much sulfuric acid is used.

- Summerlin, Lee R.; Ealy, James L. (1988). “Experiment 100: Dehydration of p-Nitroaniline: Sanke and Puff”. Chemical Demonstrations: A Sourcebook for Teachers Volume 1 (2nd ed.). American Chemical Society. p. 171. ISBN 978-0-841-21481-1.

- “Carbon Snake: demonstrating the dehydration power of concentrated sulfuric acid”. communities.acs.org. 2013-06-06. Retrieved 2022-01-31.

- Making a carbon snake with P-Nitroaniline, retrieved 2022-01-31

Toxicity

The compound is toxic by way of inhalation, ingestion, and absorption, and should be handled with care. Its LD50 in rats is 750.0 mg/kg when administered orally. 4-Nitroaniline is particularly harmful to all aquatic organisms, and can cause long-term damage to the environment if released as a pollutant.

- “4-Nitroaniline”. St. Louis, Missouri: Sigma-Aldrich. December 18, 2020.

See also

Uses

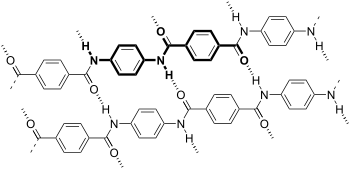

Precursor to polymers

PPD is a precursor to aramid plastics and fibers such as Kevlar and Twaron. These applications exploit PPD’s difunctionality, i.e. the presence of two amines which allow the molecules to be strung together. This polymer arises from the reaction of PPD and terephthaloyl chloride. The reaction of PPD with phosgene gives the diisocyanate, a precursor to urethane polymers.

- Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry (1 ed.). Wiley. 2003-03-11. doi:10.1002/14356007.a19_405. ISBN 978-3-527-30385-4.

Dyeing

This compound is a common hair dye. Its use is being supplanted by other aniline analogues and derivatives such as 2,5-diamino(hydroxyethylbenzene and 2,5-diaminotoluene). Other popular derivatives include tetraaminopyrimidine and indoanilines and indophenols. Derivatives of diaminopyrazole give both red and violet colours. In these applications, the nearly colourless dye precursor oxidizes to the dye.

- Thomas Clausen et al. “Hair Preparations” in Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, 2007, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a12_571.pub2

Rubber antioxidant

PPD is easily oxidized, and for this reason, derivatives of PPD are used as antiozonants in the production of rubber products (e.g., IPPD). The substituents (naphthyl, isopropyl, etc.) affect the effectiveness of their antioxidant roles as well as their properties as skin irritants.

- Hans-Wilhelm Engels et al., “Rubber, 4. Chemicals and Additives” in Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, 2007, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a23_365.pub2

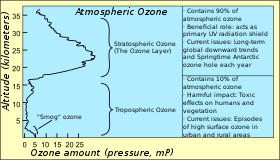

An antiozonant, also known as anti-ozonant, is an organic compound that prevents or retards damage caused by ozone. The most important antiozonants are those which prevent degradation of elastomers like rubber. A number of research projects study the application of another type of antiozonants to protect plants as well as salmonids that are affected by the chemicals.

Effect of ozone

Main article: Ozone cracking

Many elastomers are rich in unsaturated double bonds, which can react with ozone present in the air in process known as ozonolysis. This reaction breaks the polymer chains, degrading the mechanical properties of the material. The most obvious effect of this is cracking of the elastomer (ozone cracking), which is exacerbated by mechanical stress. The rate of degradation is effected both by the chemical structure of the elastomer and the amount of ozone in the environment. Elastomers which are rich in double bonds, such as natural rubber, polybutadiene, styrene-butadiene rubber and nitrile rubber are the most sensitive to degradation, whereas butyl rubber, polychloroprene, EPDM and Viton are more resistant. Ground-level ozone is naturally present, but it is also a product of smog and thus degradation is faster in areas of high air pollution. All of these factors make vehicle tires particularly vulnerable, as they contain a high level of unsaturated groups, operate in areas prone to air pollution and are subjected to significant mechanical stresses.

- Layer, R. W., & Lattimer, R. P. (1990). Protection of rubber against ozone. Rubber Chemistry and Technology, 63(3), 426-450.

Protection of elastomers

Antiozonants are used as additives in tire manufacturing to retard the effects of ozone.

- Hans-Wilhelm Engels et al., “Rubber, 4. Chemicals and Additives” in Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, 2007, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a23_365.pub2.

The most common antiozonants for elastomers are N,N′-substituted p-phenylenediamines (PPD) which can be categorized in three types:

- Dialkyl p-Phenylenediamines, such as N,N’-Di-2-butyl-1,4-phenylenediamine

- N,N′-Di-2-butyl-1,4-phenylenediamine is an aromatic amine used industrially as an antioxidant to prevent degradation of turbine oils, transformer oils, hydraulic fluids, lubricants, waxes, and greases. It is particularly effective for hydrocarbon products produced by cracking or pyrolysis, which are characterized by high alkene content. It is also used as an polymerisation inhibitor in production of various vinyl monomers such as acrylates. N,N′-Di-2-butyl-1,4-phenylenediamine has the appearance of a red liquid. It is a skin sensitizer and can be absorbed through skin. It is toxic. N,N′-Di-2-butyl-1,4-phenylenediamine is the active component of e.g. AO-22, AO-24, AO-29, and VANLUBE antioxidant mixtures, and Santoflex 44PD inhibitor.

- Alkyl-aryl p-Phenylenediamines, such as 6PPD or IPPD

- 6PPP

- 6PPD is an organic chemical widely used as stabilisingadditive (or antidegradant) in rubbers, such as NR, SBR and BR; all of which are common in vehicle tires. Although it is an effective antioxidant it is primarily used because of its excellent antiozonant performance. It is one of several antiozonants based around p-phenylenediamine. 6PPD is prepared by reductive amination of methyl isobutyl ketone (which has six carbon atoms, hence the ‘6’ in the name) with phenyl phenylenediamine (PPD). This produces a racemic mixture.

- U.S. Tire Manufacturers Association (July 15, 2021). “Statement of Sarah E. Amick Vice President EHS&S and Senior Counsel U.S. Tire Manufacturers Association”. Committee on Natural Resources Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations United States House of Representatives.

- Krüger, R H; Boissiére, C; Klein-Hartwig, K; Kretzschmar, H-J (2005). “New phenylenediamine antiozonants for commodities based on natural and synthetic rubber”. Food Addit Contam. 22 (10): 968–974. doi:10.1080/02652030500098177. PMID 16227180. S2CID 10548886.

- Hans-Wilhelm Engels et al., “Rubber, 4. Chemicals and Additives” in Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, 2007, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a23_365.pub2

- 6PPD is a common rubber antiozonant, with major application in vehicle tires. It is mobile within the rubber and slowly migrates to the surface via blooming. Here it forms a “scavenger-protective film”, reacting with the ozone more quickly than the ozone can react with the rubber. This process forms aminoxyl radicals and was first thought to degrade only to the quinone diimine, but has since been understood to continue to oxidize to quinones, amongst other products. Despite 6PPD being used in tires since the mid 1960s, its transformation to quinones was first recognized in 2020. The oxidized products are not effective antiozonants, meaning that 6PPD is a sacrificial agent.

- Lattimer, R. P.; Hooser, E. R.; Layer, R. W.; Rhee, C. K. (1 May 1983). “Mechanisms of Ozonation of N-(1,3-Dimethylbutyl)-N′-Phenyl-p-Phenylenediamine”. Rubber Chemistry and Technology. 56 (2): 431–439. doi:10.5254/1.3538136.

- Cataldo, Franco; Faucette, Brad; Huang, Semone; Ebenezer, Warren (January 2015). “On the early reaction stages of ozone with N,N′-substituted p-phenylenediamines (6PPD, 77PD) and N,N′,N”-substituted-1,3,5-triazine “Durazone®”: An electron spin resonance (ESR) and electronic absorption spectroscopy study”. Polymer Degradation and Stability. 111: 223–231. doi:10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2014.11.011.

- Cataldo, Franco (January 2018). “Early stages of p-phenylenediamine antiozonants reaction with ozone: Radical cation and nitroxyl radical formation”. Polymer Degradation and Stability. 147: 132–141. doi:10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2017.11.020.

- Seiwert, Bettina; Nihemaiti, Maolida; Troussier, Mareva; Weyrauch, Steffen; Reemtsma, Thorsten (April 2022). “Abiotic oxidative transformation of 6-PPD and 6-PPD quinone from tires and occurrence of their products in snow from urban roads and in municipal wastewater”. Water Research. 212: 118122. Bibcode:2022WatRe.21218122S. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2022.118122. PMID 35101694. S2CID 246336931.

- Tian, Zhenyu; Zhao, Haoqi; Peter, Katherine T.; Gonzalez, Melissa; Wetzel, Jill; Wu, Christopher; Hu, Ximin; Prat, Jasmine; Mudrock, Emma; Hettinger, Rachel; Cortina, Allan E.; Biswas, Rajshree Ghosh; Kock, Flávio Vinicius Crizóstomo; Soong, Ronald; Jenne, Amy; Du, Bowen; Hou, Fan; He, Huan; Lundeen, Rachel; Gilbreath, Alicia; Sutton, Rebecca; Scholz, Nathaniel L.; Davis, Jay W.; Dodd, Michael C.; Simpson, Andre; McIntyre, Jenifer K. (3 December 2020), “A ubiquitous tire rubber–derived chemical induces acute mortality in coho salmon”, Science, 371 (6525): 185–189, doi:10.1126/science.abd6951, PMID 33273063, S2CID 227281491,

… existing TWP [tire wear particle] loading, leaching, and toxicity assessments are clearly incomplete. … Accordingly, the human health effects of such exposures merit evaluation. … It is unlikely that coho salmon are uniquely sensitive … ( in print 8 Jan 2021)

- Also an erratum to this paper published in Science vol. 375, No. 6582, 18 Feb 2022 doi:10.1126/science.abo5785 reporting the updated toxicity estimates, as referenced below.

- The tendency of 6PPD to bloom towards the surface is protective because the surface film of antiozonant is replenished from reserves held within the rubber. However, this same property facilitates the transfer of 6PPD and its oxidation products into the environment as tire-wear debris. The 6PPD-quinone (6PPD-Q, CAS RN: 2754428-18-5) is of particular and increasing concern, due to its toxicity to fish. 6PPD and 6PPD-quinone enter the environment through tire-wear and are sufficiently water-soluble to enter river systems via urban runoff. From here they become widely distributed (at decreasing levels) from urban rivers through to estuaries, coasts and finally deep-sea areas. 6PPD-quinone is of environmental concern because it is toxic to coho salmon, killing them before they spawn in freshwater streams.

- Zeng, Lixi; Li, Yi; Sun, Yuxin; Liu, Liang-Ying; Shen, Mingjie; Du, Bibai (31 January 2023). “Widespread Occurrence and Transport of p -Phenylenediamines and Their Quinones in Sediments across Urban Rivers, Estuaries, Coasts, and Deep-Sea Regions”. Environmental Science & Technology. 57 (6): 2393–2403. Bibcode:2023EnST…57.2393Z. doi:10.1021/acs.est.2c07652. PMID 36720114. S2CID 256458111.

- “Pollution from car tires is killing off salmon on US west coast, study finds”. The Guardian. 3 December 2020.

- “Scientists solve mystery of mass coho salmon deaths. The killer? A chemical from car tires”. Los Angeles Times. 3 December 2020.

- Johannessen, Cassandra; Helm, Paul; Lashuk, Brent; Yargeau, Viviane; Metcalfe, Chris D. (February 2022). “The Tire Wear Compounds 6PPD-Quinone and 1,3-Diphenylguanidine in an Urban Watershed”. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology. 82 (2): 171–179. doi:10.1007/s00244-021-00878-4. PMC 8335451. PMID 34347118.

- A 2022 study also identified the toxic impact on species like brook trout and rainbow trout. The published lethal concentrations are:

- coho salmon: LC50 = 0.095 μg/L

- brook trout: LC50 = 0.59 μg/L

- rainbow trout: LC50 = 1.0 μg/L

- Markus Brinkmann; David Montgomery; Summer Selinger; Justin G. P. Miller; Eric Stock (2022-03-02), “Acute Toxicity of the Tire Rubber-Derived Chemical 6PPD-quinone to Four Fishes of Commercial, Cultural, and Ecological Importance”, Environmental Science & Technology Letters, vol. 9, no. 4, pp. 333–338, Bibcode:2022EnSTL…9..333B, doi:10.1021/acs.estlett.2c00050, S2CID 247336687

- Tian, Zhenyu; Gonzalez, Melissa; Rideout, Craig; Zhao, Hoaqi Nina; Hu, Ximin; Wetzel, Jill; Mudrock, Emma; James, C. Andrew; McIntyre, Jenifer K; Kolodziej, Edward P (11 January 2022), “6PPD-Quinone: Revised Toxicity Assessment and Quantification with a Commercial Standard”, Environmental Science & Technology Letters, 9 (2): 140–146, Bibcode:2022EnSTL…9..140T, doi:10.1021/acs.estlett.1c00910, S2CID 245893533

- It is not known why the ozone-oxidised 6PPD is toxic to coho salmon. The Nisqually and nonprofit Long Live the Kings installed a mobile stormwater filter at a bridge in the Ohop Valley in 2022. The Washington Department of Ecology, Washington State University and the US Tire Manufacturer’s Association are working on regulation and education.

- Lena Beck (17 May 2022). “Your car is killing coho salmon”. The Counter.

- 6PPD itself is deadly to rotifers, especially in combination with sodium chloride, though not at the level generally found in the runoff from road salt. A small-scale biomonitoring study in South China has shown shown both 6PPD and 6PPDQ to be present in human urine; concentrations were low but the health implications are unknown. A synthetic route to the 6PPD-quinone has been posted on ChemRxiv.

- Klauschies, Toni; Isanta-Navarro, Jana (2022-07-10). “The joint effects of salt and 6PPD contamination on a freshwater herbivore” (PDF). Science of the Total Environment. 829: 154675. Bibcode:2022ScTEn.829o4675K. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.154675. PMID 35314241. S2CID 247577987 – via Dynatrait.

- Du, Bibai; Liang, Bowen; Li, Yi; Shen, Mingjie; Liu, Liang-Ying; Zeng, Lixi (13 December 2022). “First Report on the Occurrence of N -(1,3-Dimethylbutyl)- N ′-phenyl- p -phenylenediamine (6PPD) and 6PPD-Quinone as Pervasive Pollutants in Human Urine from South China”. Environmental Science & Technology Letters. 9 (12): 1056–1062. Bibcode:2022EnSTL…9.1056D. doi:10.1021/acs.estlett.2c00821. S2CID 253828438.

- Agua, Alon; Stanton, Ryan; Pirrung, Michael (2021-02-04). “Preparation of 2-((4-Methylpentan-2-Yl)amino)-5-(Phenylamino)cyclohexa-2,5-Diene-1,4-Dione (6PPD-Quinone), an Environmental Hazard for Salmon” (PDF). ChemRxiv. doi:10.26434/chemrxiv.13698985.v1. S2CID 234062284.

- See also

- N-Isopropyl-N’-phenyl-1,4-phenylenediamine (IPPD), a related antiozonant

- N,N’-Di-2-butyl-1,4-phenylenediamine, a phenylenediamine-based antioxidant used as a fuel additive

- N-Isopropyl-N′-phenyl-1,4-phenylenediamine (often abbreviated IPPD) is an organic compound commonly used as an antiozonant in rubbers. Like other p-phenylenediamine-based antiozonants it works by virtue of its low ionization energy, which allows it to react with ozone faster than ozone will react with rubber. This reaction converts it to the corresponding aminoxyl radical (R2N–O•), with the ozone being converted to a hydroperoxyl radical (HOO•), these species can then be scavenged by other antioxidant polymer stabilizers.

- Lewis, P.M. (January 1986). “Effect of ozone on rubbers: Countermeasures and unsolved problems”. Polymer Degradation and Stability. 15 (1): 33–66. doi:10.1016/0141-3910(86)90004-2.

- Cataldo, Franco (January 2018). “Early stages of p-phenylenediamine antiozonants reaction with ozone: Radical cation and nitroxyl radical formation”. Polymer Degradation and Stability. 147: 132–141. doi:10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2017.11.020.

- IPPD is prone to process called blooming, where it migrates to the surface of the rubber. This can be beneficial to the tire, as ozone attacks the tire surface and blooming therefore moves the antiozonant to where it is most needed, however this also increases the leaching of IPPD into the environment. Many tire producers have moved to using 6PPD instead, as this migrates more slowly. Oxidation of IPPD converts the central phenylenediamine ring into a quinone.

- Choi, Sung-Seen (5 July 1997). “Migration of Antidegradants to the Surface in NR and SBR Vulcanizates”. Journal of Applied Polymer Science. 65 (1): 117–125. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4628(19970705)65:1<117::AID-APP15>3.0.CO;2-0.

- Ignatz-Hoover, Frederick; To, Byron H.; Datta, R. N.; De Hoog, Arie J.; Huntink, N. M.; Talma, A. G. (1 July 2003). “Chemical Additives Migration in Rubber”. Rubber Chemistry and Technology. 76 (3): 747–768. doi:10.5254/1.3547765.

- Cao, Guodong; Wang, Wei; Zhang, Jing; Wu, Pengfei; Zhao, Xingchen; Yang, Zhu; Hu, Di; Cai, Zongwei (5 April 2022). “New Evidence of Rubber-Derived Quinones in Water, Air, and Soil”. Environmental Science & Technology. 56 (7): 4142–4150. Bibcode:2022EnST…56.4142C. doi:10.1021/acs.est.1c07376. PMC 8988306. PMID 35316033.

- IPPD is a human allergen. It is the compound responsible for coining the term “Volkswagen Dermatitis”. There is some preliminary evidence for it being harmful to fish.

- Lammintausta, K; Kalimo, K (1985). “Sensitivity to Rubber. Study with Rubber Mixes and Individual Rubber Chemicals”. Dermatosen in Beruf und Umwelt. Occupation and Environment. 33 (6): 204–8. PMID 2936592.

- Conde-Salazar, Luis; del-Río, Emilio; Guimaraens, Dolores; Domingo, Antonia González (August 1993). “Type IV Allergy to Rubber Additives: A 10-Year Study of 686 Cases”. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 29 (2): 176–180. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(93)70163-N. PMID 8335734.

- Jordan, William P. Jr. (1971-01-01). “Contact Dermatitis From N-Isopropyl-N-Phenylparaphenylenediamine: “Volkswagen Dermatitis””. Archives of Dermatology. 103 (1): 85–87. doi:10.1001/archderm.1971.04000130087014. ISSN 0003-987X.

- Zhong, Liqiao; Peng, Weijuan; Liu, Chunsheng; Gao, Lei; Chen, Daqing; Duan, Xinbin (July 2022). “IPPD-induced growth inhibition and its mechanism in zebrafish”. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety. 239: 113614. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2022.113614. PMID 35567929. S2CID 248728812.

- See also

- N,N′-Di-2-butyl-1,4-phenylenediamine – a phenylenediamine based antioxidant used as a fuel additive

- 6PPD is an organic chemical widely used as stabilisingadditive (or antidegradant) in rubbers, such as NR, SBR and BR; all of which are common in vehicle tires. Although it is an effective antioxidant it is primarily used because of its excellent antiozonant performance. It is one of several antiozonants based around p-phenylenediamine. 6PPD is prepared by reductive amination of methyl isobutyl ketone (which has six carbon atoms, hence the ‘6’ in the name) with phenyl phenylenediamine (PPD). This produces a racemic mixture.

- 6PPP

- Diaryl p-Phenylenediamines, like DPPD

Other classes include:

- Styrenated phenol (SPH), styrenated and alkylated phenol (SAPH)

- Hydrocarbon waxes which create a surface barrier, preventing contact with ozone: paraffin wax, microcrystalline wax.

Protection of plants

For the protection of plants like winter wheat[citation needed] or maize.

- Singh, Aditya Abha; Chaurasia, Meenakshi; Gupta, Vaishali; Agrawal, Madhoolika; Agrawal, S. B. (May 2018). “Responses of Zea mays L. cultivars ‘Buland’ and ‘Prakash’ to an antiozonant ethylene diurea grown under ambient and elevated levels of ozone”. Acta Physiologiae Plantarum. 40 (5): 92. doi:10.1007/s11738-018-2666-z. ISSN 0137-5881. S2CID 13832708.

Ethylene diurea (EDU) has been used successfully as antiozonant.

- Ethylene diurea (EDU) is an organic compound with the formula (CH2NHCONH2)2. It is a white solid. The compound has attracted interest as a potential antiozonant for crop protection. With respect to preventing the harmful effects on crops by ozone, EDU appears to either prevent the harmful effects of ozone or it stimulated plant growth. Trees treated with EDU were significantly healthier in both leaf longevity and water use efficiency. The effectiveness of EDU depends upon several environmental factors.

- Bachmann, W. E.; Horton, W. J.; Jenner, E. L.; MacNaughton, N. W.; Maxwell, C. E. (1950). “The Nitration of Derivatives of Ethylenediamine1”. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 72 (7): 3132–3134. doi:10.1021/ja01163a090. ISSN 0002-7863.

- Archambualt, Daniel; Li, Xiaomei (January 2002). “Evaluation of the Anti-oxidant Ethylene Diurea (EDU) as a protectant against Ozone effects on Crops” (PDF). Alberta Environment. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-04-09. Retrieved 2012-10-12.

- Hoshika Y, Omasa K, Paoletti E (2012). “Whole-tree water use efficiency is decreased by ambient ozone and not affected by O3-induced stomatal sluggishness”. PLOS ONE. 7 (6): e39270. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0039270. PMC 3377656. PMID 22723982.

- Ribas, A.; Peñuelas, J. (2000). “Effects of Ethylene diurea as a protective antiozonant on beans (Phaseolus vulgaris cv Lit) exposed to different tropospheric ozone doses in Catalonia (NE Spain)”. Water, Air, and Soil Pollution. 117 (1/4): 263–271. doi:10.1023/A:1005138120490. ISSN 0049-6979. S2CID 93318643.

- See also

Other uses

A substituted form of PPD sold under the name CD-4 is also used as a developing agent in the C-41 color photographic film development process, reacting with the silver grains in the film and creating the colored dyes that form the image.

- The C-41 process is the same for all C-41 films, although different manufacturers’ processing chemistries vary slightly. After exposure, the film is developed in a “color developer”. The developing ingredient is a paraphenylene diamine-based chemical known as CD-4. The developer develops the silver in the emulsion layers. As the silver is developing, oxidized developer reacts with the dye couplers, resulting in formation of dyes. The control of temperature and agitation of the film in the developer is critical in obtaining consistent, accurate results. Incorrect temperature can result in severe color shifts or significant under- or overdevelopment of the film. After the developer, a bleach converts the metallic silver generated by development to silver halide, which is soluble in fixer. After the bleach, a fixer removes the silver halide. This is followed by a wash, and a final stabilizer and rinse to complete the process. There are simplified versions of the process that use a combined bleach-fix (EDTA) that dissolves the silver generated by development and removes undeveloped silver halide. These are not used by commercial C-41 processors, and are marketed for home or field use.

- The fourth in the series of color developing agents used in developing color films, commonly known as CD-4, is chemically known as 4-(N-Ethyl-N-2-hydroxyethyl)-2-methylphenylenediamine sulfate. In color development, after reducing a silver atom in a silver halide crystal, the oxidized developing agent combines with a color coupler to form a color dye molecule.

- “Ethanol, 2-((4-amino-3-methylphenyl)ethylamino)-, sulfate (1:1) (salt)”. U.S. National Center for Biotechnology Information. Retrieved 7 April 2019.

- See Also

PPD is also used as a Henna surrogate for temporary tattoos. Its usage can lead to severe contact dermatitis. Oh…they forget the side effect of death. The internet suggests young people, primarily girls, are committing suicide with this stuff. Not sure I believe the deaths are suicides.

“Suicide by self-poisoning is a common cause of death, especially in the younger population. More specifically, hair-dye poisoning is being increasingly used for suicide. Paraphenylenediamine (PPD), also known as “Kala pathar”, is a highly toxic ingredient present in hair-dye that can cause death.”

- Omer Sultan M, Inam Khan M, Ali R, Farooque U, Hassan SA, Karimi S, Cheema O, Pillai B, Asghar F, Javed R. Paraphenylenediamine (Kala Pathar) Poisoning at the National Poison Control Center in Karachi: A Prospective Study. Cureus. 2020 May 29;12(5):e8352. doi: 10.7759/cureus.8352. PMID: 32617225; PMCID: PMC7325408.

There are three pages of results when I type the search criteria into PMC. These are from page 1.

- A systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence and complications of paraphenylenediamine-containing hair dye poisoning in developing countries Akshaya Srikanth Bhagavathula, Deepak Kumar Bandari, Moien Khan, Abdulla ShehabIndian J Pharmacol. 2019 Sep-Oct; 51(5): 302–315. Published online 2019 Nov 26. doi: 10.4103/ijp.IJP_246_17PMCID: PMC6892014

- Characteristic autopsy findings in hair dye poisoning Chittaranjan Behera, Asit Ranjan Mridha, Rajesh Kumar, Tabin Millo BMJ Case Rep. 2015; 2015: bcr2014206692. Published online 2015 Feb 7. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2014-206692PMCID: PMC4330428

- Analytical Investigations of Toxic p-Phenylenediamine (PPD) Levels in Clinical Urine Samples with Special Focus on MALDI-MS/MS Gero P. Hooff, Nick A. van Huizen, Roland J. W. Meesters, Eduard E. Zijlstra, Mohamed Abdelraheem, Waleed Abdelraheem, Mohamed Hamdouk, Jan Lindemans, Theo M. Luider PLoS One. 2011; 6(8): e22191. Published online 2011 Aug 4. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022191PMCID: PMC3150356

- Suicide by poisoning in Pakistan: review of regional trends, toxicity and management of commonly used agents in the past three decades Maria Safdar, Khalid Imran Afzal, Zoe Smith, Filza Ali, Pervaiz Zarif, Zahid Farooq Baig BJPsych Open. 2021 Jul; 7(4): e114. Published online 2021 Jun 17. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2021.923PMCID: PMC8240123

- Clinical presentation, treatment and outcome of paraphenylene-diamine induced acute kidney injury following hair dye poisoning: a cohort study Mazin Shigidi, Osama Mohammed, Mohammed Ibrahim, Elshafie Taha Pan Afr Med J. 2014; 19: 163. Published online 2014 Oct 16. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2014.19.163.3740PMCID: PMC4362623

- Accuracy of Rapid Emergency Medicine Score and Sequential Organ Failure Assessment Score in predicting acute paraphenylenediamine poisoning adverse outcomes Ghada N. El-Sarnagawy, Mona M. Ghonem, Marwa A. Abdelhameid, Omaima M. Ali, Asmaa M. Ismail, Doaa M. El Shehaby Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2023; 30(12): 32489–32506. Published online 2022 Dec 3. doi: 10.1007/s11356-022-24427-1PMCID: PMC10017625

- Paraphenylenediamine (Kala Pathar) Poisoning at the National Poison Control Center in Karachi: A Prospective Study Muhammad Omer Sultan, Muhammad Inam Khan, Rahmat Ali, Umar Farooque, Syed Adeel Hassan, Sundas Karimi, Omer Cheema, Bharat Pillai, Fahham Asghar, Rafay Javed Cureus. 2020 May; 12(5): e8352. Published online 2020 May 29. doi: 10.7759/cureus.8352PMCID: PMC7325408

- Paraphenylenediamine (Hair Dye) Poisoning: A Prospective Study on the Clinical Outcome and Side Effects Profile Sohaib Asghar, Summayha Mahbub, Shoaib Asghar, Salman Shahid Cureus. 2022 Sep; 14(9): e29133. Published online 2022 Sep 13. doi: 10.7759/cureus.29133PMCID: PMC9561809

- Suicides by pesticide ingestion in Pakistan and the impact of pesticide regulation Shweta Dabholkar, Shahina Pirani, Mark Davis, Murad Khan, Michael Eddleston BMC Public Health. 2023; 23: 676. Published online 2023 Apr 11. doi: 10.1186/s12889-023-15505-1PMCID: PMC10088141

- Paraphenylenediamine (PPD) Poisoning Mistaken for an Anaphylactic Reaction Mohamed Elgassim, Khalid Y Fadul, Mohammed Abbas, Faten AlBakri, Raghav Kamath, Waleed Salem Cureus. 2022 Feb; 14(2): e22503. Published online 2022 Feb 22. doi: 10.7759/cureus.22503PMCID: PMC8956479

- Importance of pesticides for lethal poisoning in India during 1999 to 2018: a systematic review Ayanthi Karunarathne, Ashish Bhalla, Aastha Sethi, Uditha Perera, Michael Eddleston BMC Public Health. 2021; 21: 1441. Published online 2021 Jul 22. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-11156-2PMCID: PMC8296580

- Sociodemographic Characteristics and Patterns of Suicide in Pakistan: An Analysis of Current Trends Sadiq Naveed, Sania Mumtaz Tahir, Nazish Imran, Bariah Rafiq, Maryam Ayub, Imran Ijaz Haider, Murad Moosa Khan Community Ment Health J. 2023 Jan 7 : 1–7. doi: 10.1007/s10597-022-01086-7 [Epub ahead of print]PMCID: PMC9825092

- Pattern of Adolescent Suicides in Pakistan: A content analysis of Newspaper reports of two years Nazish Imran, Sadiq Naveed, Bariah Rafiq, Sania Mumtaz Tahir, Maryam Ayub, Imran Ijaz Haider Pak J Med Sci. 2023 Jan-Feb; 39(1): 6–11. doi: 10.12669/pjms.39.1.6851PMCID: PMC9843018

- Incidence and outcome of laryngeal edema and rhabdomyolysis after ingestion of black rock Aml Ahmed Sayed, Abdelrahman Hamdy Abdelrahman, Zein Elabdeen Ahmed Sayed, Marwa Ahmed Abdelhameid Int J Emerg Med. 2024; 17: 2. Published online 2024 Jan 2. doi: 10.1186/s12245-023-00577-yPMCID: PMC10759383

- Abstracts Int J Legal Med. 2021; 135(Suppl 1): 11–119. Published online 2021 May 15. doi: 10.1007/s00414-021-02613-zPMCID: PMC8123097

- Paraphenylene diamine poisoning A.C. Jesudoss Prabhakaran Indian J Pharmacol. 2012 May-Jun; 44(3): 423–424. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.96356PMCID: PMC3371476

- Paraphenylene diamine poisoning A. C. Jesudoss Prabhakaran J Nat Sci Biol Med. 2012 Jul-Dec; 3(2): 199–200. doi: 10.4103/0976-9668.101924Retraction in: J Nat Sci Biol Med. 2016 Jul-Dec; 7(2): 201.PMCID: PMC3510919

- Super Vasmol Poisoning: Dangers of Darker Shade Subramanian Senthilkumaran, Narendra N Jena, Ponniah Thirumalaikolundusubramanian Indian J Crit Care Med. 2019 Dec; 23(Suppl 4): S287–S289. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10071-23303PMCID: PMC6996661

- A small peptide antagonist of the Fas receptor inhibits neuroinflammation and prevents axon degeneration and retinal ganglion cell death in an inducible mouse model of glaucoma Anitha Krishnan, Andrew J. Kocab, David N. Zacks, Ann Marshak-Rothstein, Meredith Gregory-Ksander J Neuroinflammation. 2019; 16: 184. Published online 2019 Sep 30. doi: 10.1186/s12974-019-1576-3PMCID: PMC6767653 (WHY IS THIS HERE? LOOK IT UP – APPEARS TO BE STAINING RELATED)

- Downregulation of apolipoprotein A-IV in plasma & impaired reverse cholesterol transport in individuals with recent acts of deliberate self-harm Boby Mathew, Krishnamachari Srinivasan, Johnson Pradeep, Tinku Thomas, Shakuntala Kandikuppa Murthy, Amit Kumar Mandal Indian J Med Res. 2019 Oct; 150(4): 365–375. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_1842_17PMCID: PMC6902365 (LOOK THIS UP TOO – INTERESTING)

- Black henna powder may be derived from indigo (from the plant Indigofera tinctoria). It may also contain unlisted dyes and chemicals such as para-phenylenediamine (PPD), which can stain skin black quickly, but can cause severe allergic reactions and permanent scarring if left on for more than 2–3 days. The FDA specifically forbids PPD to be used for this purpose, and may prosecute those who produce black henna. Artists who injure clients with black henna in the U.S. may be sued for damages.

- Singh, M.; Jindal, S. K.; Kavia, Z. D.; Jangid, B. L.; Khem Chand (2005). “Traditional Methods of Cultivation and Processing of Henna. Henna, Cultivation, Improvement and Trade”. Henna: Cultivation, Improvement, and Trade. Jodhpur: Central Arid Zone Research Institute. pp. 21–24. OCLC 124036118.[page needed]

- “FDA.gov”. Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 2 January 2011. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- “Rosemariearnold.com”. Archived from the original on 15 July 2011. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- The name arose from imports of plant-based hair dyes into the West in the late 19th century. Partly fermented, dried indigo was called black henna because it could be used in combination with henna to dye hair black. This gave rise to the belief that there was such a thing as black henna which could dye skin black. Indigo will not dye skin black. Pictures of indigenous people with black body art (either alkalized henna or from some other source) also fed the belief that there was such a thing as black henna.[citation needed]

- In the 1990s, henna artists in Africa, India, Bali, the Arabian Peninsula and the West began to experiment with PPD-based black hair dye, applying it as a thick paste as they would apply henna, in an effort to find something that would quickly make jet-black temporary body art. PPD can cause severe allergic reactions, with blistering, intense itching, permanent scarring, and permanent chemical sensitivities. Estimates of allergic reactions range between 3% and 15%. Henna does not cause these injuries. Black henna made with PPD can cause lifelong sensitization to coal tar derivatives while black henna made with gasoline, kerosene, lighter fluid, paint thinner, and benzene has been linked to adult acute leukemia.

- Van den Keybus, C.; Morren, M.-A.; Goossens, A. (September 2005). “Walking difficulties due to an allergic reaction to a temporary tattoo”. Contact Dermatitis. 53 (3): 180–181. doi:10.1111/j.0105-1873.2005.0407m.x. PMID 16128770. S2CID 28624688.

- Stante, M; Giorgini, S; Lotti, T (April 2006). “Allergic contact dermatitis from henna temporary tattoo”. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 20 (4): 484–486. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.01483.x. PMID 16643167. S2CID 43067542.

- Jung, Peter; Sesztak-Greinecker, Gabriele; Wantke, Felix; Gotz, Manfred; Jarisch, Reinhart; Hemmer, Wolfgang (April 2006). “A painful experience: black henna tattoo causing severe, bullous contact dermatitis”. Contact Dermatitis. 54 (4): 219–220. doi:10.1111/j.0105-1873.2006.0775g.x. PMID 16650103. S2CID 43613761.

- Hassan, Inaam Bashir; Islam, Sherief I. A. M.; Alizadeh, Hussain; Kristensen, Jorgen; Kambal, Amr; Sonday, Shanaaz; Bernseen, Roos M. D. (21 July 2009). “Acute leukemia among the adult population of United Arab Emirates: an epidemiological study”. Leukemia & Lymphoma. 50 (7): 1138–1147. doi:10.1080/10428190902919184. PMID 19557635. S2CID 205701235.

- The most frequent serious health consequence of having a black henna temporary tattoo is sensitization to hair dye and related chemicals. If a person has had a black henna tattoo and later dyes their hair with chemical hair dye, the allergic reaction may be life-threatening and require hospitalization. Because of the epidemic of PPD allergic reactions, chemical hair dye products now post warnings on the labels: “Temporary black henna tattoos may increase your risk of allergy. Do not colour your hair if: … – you have experienced a reaction to a temporary black henna tattoo in the past.”

- Sosted, Heidi; Johansen, Jeanne Duus; Andersen, Klaus Ejner; Menne, Torkil (February 2006). “Severe allergic hair dye reactions in 8 children”. Contact Dermatitis. 54 (2): 87–91. doi:10.1111/j.0105-1873.2006.00746.x. PMID 16487280. S2CID 39281376.

- Commission Directive 2009/134/EC of 28 October 2009 amending Council Directive 76/768/EEC concerning cosmetic products for the purposes of adapting Annex III thereto to technical progress

- PPD is illegal for use on skin in western countries, though enforcement is difficult. Physicians have urged governments to legislate against black henna because of the frequency and severity of injuries, especially to children. To assist the prosecution of vendors, government agencies encourage citizens to report injuries and illegal use of PPD black henna. When used in hair dye, the PPD amount must be below 6%, and application instructions warn that the dye must not touch the scalp and must be quickly rinsed away. Black henna pastes have PPD percentages from 10% to 80%, and are left on the skin for half an hour.

- Jacob, Sharon E.; Zapolanski, Tamar; Chayavichitsilp, Pamela; Connelly, Elizabeth Alvarez; Eichenfield, Lawrence F. (1 August 2008). “p-Phenylenediamine in Black Henna Tattoos”. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 162 (8): 790–2. doi:10.1001/archpedi.162.8.790. PMID 18678815.

- “Black Henna”. Florida Department of Health. 20 December 2018. Archived from the original on 29 March 2021. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- “Health Canada alerts Canadians not to use ‘black henna’ temporary tattoo ink and paste containing PPD” (Press release). Health Canada. 11 August 2003. Archived from the original on 10 June 2008.

- Avnstorp, Christian; Rastogi, Suresh C.; Menne, Torkil (August 2002). “Acute fingertip dermatitis from a temporary tattoo and quantitative chemical analysis of the product”. Contact Dermatitis. 47 (2): 109–125. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0536.2002.470210_11.x. PMID 12455547. S2CID 34550567.

- Kang, Ik-Joon; Lee, Mu-Hyoung (July 2006). “Quantification of para-phenylenediamine and heavy metals in henna dye”. Contact Dermatitis. 55 (1): 26–29. doi:10.1111/j.0105-1873.2006.00845.x. PMID 16842550. S2CID 22176978.

- PPD black henna use is widespread, particularly in tourist areas. Because the blistering reaction appears 3 to 12 days after the application, most tourists have left and do not return to show how much damage the artist has done. This permits the artists to continue injuring others, unaware they are causing severe injuries. The high-profit margins of black henna and the demand for body art that emulates “tribal tattoos” further encourage artists to deny the dangers.

- Marcoux, Danielle; Couture‐Trudel, Pierre‐Marc; Riboulet‐Delmas, Gisèle; Sasseville, Denis (23 November 2002). “Sensitization to Para‐Phenylenediamine from a Streetside Temporary Tattoo”. Pediatric Dermatology. 19 (6): 498–502. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1470.2002.00218.x. PMID 12437549. S2CID 23543707.

- Onder, Meltem; Atahan, Cigdem Asena; Oztas, Pinar; Oztas, Murat Orhan (September 2001). “Temporary henna tattoo reactions in children”. International Journal of Dermatology. 40 (9): 577–579. doi:10.1046/j.1365-4362.2001.01248.x. PMID 11737452. S2CID 221816034.

- Onder, M (July 2003). “Temporary holiday ‘tattoos’ may cause lifelong allergic contact dermatitis when henna is mixed with PPD”. Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology. 2 (3–4): 126–130. doi:10.1111/j.1473-2130.2004.00083.x. PMID 17163917. S2CID 38957088.

- It is not difficult to recognize and avoid PPD black henna:

- if a paste stains skin on the torso black in less than ½ hour, it has PPD in it.

- if the paste is mixed with peroxide, or if peroxide is wiped over the design to bring out the color, it has PPD in it.

- “PPD In ‘Black Henna’ Temporary Tattoos Is Not Safe”. Health Canada. 16 December 2008. Archived from the original on 24 April 2010. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- PPD sensitivity is lifelong. A person who has become sensitized through black henna tattoos may have future allergic reactions to perfumes, printer ink, chemical hair dyes, textile dye, photographic developer, sunscreen and some medications. A person who has had a black henna tattoo should consult their physician about the health consequences of PPD sensitization.

- Moro, Paola; Morina, Marco; Milani, Fabrizia; Pandolfi, Marco; Guerriero, Francesca; Bernardo, Luca (11 July 2016). “Sensitization and Clinically Relevant Allergy to Hair Dyes and Clothes from Black Henna Tattoos: Do People Know the Risk? An Uncommon Serious Case and a Review of the Literature”. Cosmetics. 3 (3): 23. doi:10.3390/cosmetics3030023. ISSN 2079-9284.

- “Dangers of black henna”. nhs.uk. 26 April 2018. Archived from the original on 8 August 2020. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

PPD is also used as a histological stain for lipids such as myelin.

PPD is used by lichenologists in the PD test to aid identification of Lichens. PPD is used extensively as a cross-linking agent in the formation of COFs (covalent organic frameworks), which have a number of applications in dyes and aromatic compounds adsorption.

- “Chemical Tests”. The British Lichen Society. Retrieved 2019-04-30.

P test

This is also known as the PD test. It uses a 1–5% ethanolic solution of para-phenylenediamine (PD), made by placing a drop of ethanol (70–95%) over a few crystals of the chemical; this yields an unstable, light sensitive solution that lasts for about a day. An alternative form of this solution, called Steiner’s solution, is much longer lasting although it produces less intense colour reactions. It is typically prepared by dissolving 1 gram of PD, 10 grams of sodium sulfite, and 0.5 millilitres of detergent in 100 millilitres of water; initially pink in colour, the solution becomes purple with age. Steiner’s solution will last for months. The phenylenediamine reacts with aldehydes to yield Schiff bases according to the following reaction:[8]R−CHO + H2N−C6H4−NH2 → R−CH=N−C6H4−NH2 + H2O Products of this reaction are yellow to red in colour. Most β-orcinol depsidones and some β-orcinol depsides will react positively. PD is poisonous both as a powder and a solution, and surfaces that come in contact with it (including skin) will discolour.

- Ahmadjian, Vernon; Hale, Mason E. (1973). The Lichens. New York: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-044950-7. pp. 636–637.

- Dahl, Eilif; Krog, Hildur (1973). Macrolichens of Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden. Universitetsforlaget. ISBN 9788200022626. p. 23.

- Sharnoff, Stephen (2014). A Field Guide to California Lichens. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 369–371. ISBN 978-0-300-19500-2. OCLC 862053107.

- Le Pogam, Pierre; Herbette, Gaëtan; Boustie, Joël (19 December 2014). “Analysis of Lichen Metabolites, a Variety of Approaches”. Recent Advances in Lichenology. New Delhi: Springer India. pp. 229–261. doi:10.1007/978-81-322-2181-4_11. ISBN 978-81-322-2180-7.

Safety

The aquatic LD50 of PPD is 0.028 mg/L. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency reported that in rats and mice chronically exposed to PPD in their diet, it simply depressed body weights, and no other clinical signs of toxicity were observed in several studies. One review of 31 English-language articles published between January 1992 and February 2005 that investigated the association between personal hair dye use and cancer as identified through the PubMed search engine found “at least one well-designed study with detailed exposure assessment” that observed associations between personal hair dye use and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, multiple myeloma, acute leukemia, and bladder cancer, but those associations were not consistently observed across studies. A formal meta-analysis was not possible due to the heterogeneity of the exposure assessment across the studies.

- Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry (1 ed.). Wiley. 2003-03-11. doi:10.1002/14356007.a19_405. ISBN 978-3-527-30385-4.

- p-Phenylenediamine, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

- Rollison, DE; Helzlsouer, KJ; Pinney, SM (2006). “Personal hair dye use and cancer: a systematic literature review and evaluation of exposure assessment in studies published since 1992”. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health Part B: Critical Reviews. 9 (5): 413–39. Bibcode:2006JTEHB…9..413R. doi:10.1080/10937400600681455. PMID 17492526. S2CID 23749135.

In 2005–06, it was the tenth-most-prevalent allergen in patch tests (5.0%).

- Zug, Kathryn A.; Warshaw, Erin M.; Fowler, Joseph F.; Maibach, Howard I.; Belsito, Donald L.; Pratt, Melanie D.; Sasseville, Denis; Storrs, Frances J.; Taylor, James S.; Mathias, C. G. Toby; Deleo, Vincent A.; Rietschel, Robert L.; Marks, James (2009). “Patch-test results of the North American Contact Dermatitis Group 2005-2006”. Dermatitis: Contact, Atopic, Occupational, Drug. 20 (3): 149–160. doi:10.2310/6620.2009.08097. ISSN 2162-5220. PMID 19470301. S2CID 24088485.

The CDC lists PPD as being a contact allergen. Exposure routes are through inhalation, skin absorption, ingestion, and skin and/or eye contact. Symptoms of exposure to PPD include throat irritation (pharynx and larynx), bronchial asthma, and sensitization dermatitis. Sensitization is a lifelong issue, which may lead to active sensitization to products, including but not limited to black clothing, various inks, hair dye, dyed fur, dyed leather, and certain photographic products. It was voted Allergen of the Year in 2006 by the American Contact Dermatitis Society.

- “The NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards”. Archived from the original on 2017-10-24. Retrieved 2017-09-07.

- “NIOSH Registry of Toxic Effects of Chemical Substances (RTECS) entry for p-Phenylenediamine (PPD)”. Archived from the original on 2010-03-31. Retrieved 2017-09-07.

Poisoning by PPD is rare in Western countries.In contrast, poisoning by PPD has occurred in Eastern countries, such as Pakistan, where people have committed suicide by consuming it.

- Ashraf, W.; Dawling, S.; Farrow, L. J. (1994). “Systemic Paraphenylenediamine (PPD) Poisoning: A Case Report and Review”. Human & Experimental Toxicology. 13 (3): 167–70. Bibcode:1994HETox..13..167A. doi:10.1177/096032719401300305. PMID 7909678. S2CID 31229733.

- Omer Sultan, Muhammad; Inam Khan, Muhammad; Ali, Rahmat; Farooque, Umar; Hassan, Syed Adeel; Karimi, Sundas; Cheema, Omer; Pillai, Bharat; Asghar, Fahham; Javed, Rafay (2020-05-29). “Paraphenylenediamine (Kala Pathar) Poisoning at the National Poison Control Center in Karachi: A Prospective Study”. Cureus. 12 (5): e8352. doi:10.7759/cureus.8352. ISSN 2168-8184. PMC 7325408. PMID 32617225.

See also

References

- Merck Index, 11th Edition, 7256

- “P-Phenylenediamine (1,4-Diaminobenzene)”. Archived from the original on 2012-03-13. Retrieved 2011-07-14.

- NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. “#0495”. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- Haynes, William M., ed. (2016). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (97th ed.). CRC Press. pp. 5–89. ISBN 978-1498754286.

- “p-Phenylene diamine”. Immediately Dangerous to Life or Health Concentrations (IDLH). National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- “p-Phenylenediamine MSDS”. Thermo Fisher Scientific.

- Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry (1 ed.). Wiley. 2003-03-11. doi:10.1002/14356007.a19_405. ISBN 978-3-527-30385-4.

- Thomas Clausen et al. “Hair Preparations” in Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, 2007, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a12_571.pub2

- Hans-Wilhelm Engels et al., “Rubber, 4. Chemicals and Additives” in Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, 2007, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a23_365.pub2

- “Chemical Tests”. The British Lichen Society. Retrieved 2019-04-30.

- p-Phenylenediamine, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

- Rollison, DE; Helzlsouer, KJ; Pinney, SM (2006). “Personal hair dye use and cancer: a systematic literature review and evaluation of exposure assessment in studies published since 1992”. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health Part B: Critical Reviews. 9 (5): 413–39. Bibcode:2006JTEHB…9..413R. doi:10.1080/10937400600681455. PMID 17492526. S2CID 23749135.

- Zug, Kathryn A.; Warshaw, Erin M.; Fowler, Joseph F.; Maibach, Howard I.; Belsito, Donald L.; Pratt, Melanie D.; Sasseville, Denis; Storrs, Frances J.; Taylor, James S.; Mathias, C. G. Toby; Deleo, Vincent A.; Rietschel, Robert L.; Marks, James (2009). “Patch-test results of the North American Contact Dermatitis Group 2005-2006”. Dermatitis: Contact, Atopic, Occupational, Drug. 20 (3): 149–160. doi:10.2310/6620.2009.08097. ISSN 2162-5220. PMID 19470301. S2CID 24088485.

- “The NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards”. Archived from the original on 2017-10-24. Retrieved 2017-09-07.

- “NIOSH Registry of Toxic Effects of Chemical Substances (RTECS) entry for p-Phenylenediamine (PPD)”. Archived from the original on 2010-03-31. Retrieved 2017-09-07.

- Ashraf, W.; Dawling, S.; Farrow, L. J. (1994). “Systemic Paraphenylenediamine (PPD) Poisoning: A Case Report and Review”. Human & Experimental Toxicology. 13 (3): 167–70. Bibcode:1994HETox..13..167A. doi:10.1177/096032719401300305. PMID 7909678. S2CID 31229733.

- Omer Sultan, Muhammad; Inam Khan, Muhammad; Ali, Rahmat; Farooque, Umar; Hassan, Syed Adeel; Karimi, Sundas; Cheema, Omer; Pillai, Bharat; Asghar, Fahham; Javed, Rafay (2020-05-29). “Paraphenylenediamine (Kala Pathar) Poisoning at the National Poison Control Center in Karachi: A Prospective Study”. Cureus. 12 (5): e8352. doi:10.7759/cureus.8352. ISSN 2168-8184. PMC 7325408. PMID 32617225.

- Layer, R. W., & Lattimer, R. P. (1990). Protection of rubber against ozone. Rubber Chemistry and Technology, 63(3), 426-450.

- Hans-Wilhelm Engels et al., “Rubber, 4. Chemicals and Additives” in Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, 2007, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a23_365.pub2.

- 6PPP

- IPPD Archived December 5, 2008, at the Wayback Machine (product page)

- Antioxidants & Antidegradants

- Singh, Aditya Abha; Chaurasia, Meenakshi; Gupta, Vaishali; Agrawal, Madhoolika; Agrawal, S. B. (May 2018). “Responses of Zea mays L. cultivars ‘Buland’ and ‘Prakash’ to an antiozonant ethylene diurea grown under ambient and elevated levels of ozone”. Acta Physiologiae Plantarum. 40 (5): 92. doi:10.1007/s11738-018-2666-z. ISSN 0137-5881. S2CID 13832708.

- Bachmann, W. E.; Horton, W. J.; Jenner, E. L.; MacNaughton, N. W.; Maxwell, C. E. (1950). “The Nitration of Derivatives of Ethylenediamine1”. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 72 (7): 3132–3134. doi:10.1021/ja01163a090. ISSN 0002-7863.

- Archambualt, Daniel; Li, Xiaomei (January 2002). “Evaluation of the Anti-oxidant Ethylene Diurea (EDU) as a protectant against Ozone effects on Crops” (PDF). Alberta Environment. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-04-09. Retrieved 2012-10-12.

- Hoshika Y, Omasa K, Paoletti E (2012). “Whole-tree water use efficiency is decreased by ambient ozone and not affected by O3-induced stomatal sluggishness”. PLOS ONE. 7 (6): e39270. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0039270. PMC 3377656. PMID 22723982.

- Ribas, A.; Peñuelas, J. (2000). “Effects of Ethylene diurea as a protective antiozonant on beans (Phaseolus vulgaris cv Lit) exposed to different tropospheric ozone doses in Catalonia (NE Spain)”. Water, Air, and Soil Pollution. 117 (1/4): 263–271. doi:10.1023/A:1005138120490. ISSN 0049-6979. S2CID 93318643.

- “N,N′-Di-sec-butyl-p-phenylenediamine”. Sigma-Aldrich.

- U.S. Tire Manufacturers Association (July 15, 2021). “Statement of Sarah E. Amick Vice President EHS&S and Senior Counsel U.S. Tire Manufacturers Association”. Committee on Natural Resources Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations United States House of Representatives.

- Krüger, R H; Boissiére, C; Klein-Hartwig, K; Kretzschmar, H-J (2005). “New phenylenediamine antiozonants for commodities based on natural and synthetic rubber”. Food Addit Contam. 22 (10): 968–974. doi:10.1080/02652030500098177. PMID 16227180. S2CID 10548886.

- Hans-Wilhelm Engels et al., “Rubber, 4. Chemicals and Additives” in Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, 2007, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a23_365.pub2

- Lattimer, R. P.; Hooser, E. R.; Layer, R. W.; Rhee, C. K. (1 May 1983). “Mechanisms of Ozonation of N-(1,3-Dimethylbutyl)-N′-Phenyl-p-Phenylenediamine”. Rubber Chemistry and Technology. 56 (2): 431–439. doi:10.5254/1.3538136.

- Cataldo, Franco; Faucette, Brad; Huang, Semone; Ebenezer, Warren (January 2015). “On the early reaction stages of ozone with N,N′-substituted p-phenylenediamines (6PPD, 77PD) and N,N′,N”-substituted-1,3,5-triazine “Durazone®”: An electron spin resonance (ESR) and electronic absorption spectroscopy study”. Polymer Degradation and Stability. 111: 223–231. doi:10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2014.11.011.

- Cataldo, Franco (January 2018). “Early stages of p-phenylenediamine antiozonants reaction with ozone: Radical cation and nitroxyl radical formation”. Polymer Degradation and Stability. 147: 132–141. doi:10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2017.11.020.

- Seiwert, Bettina; Nihemaiti, Maolida; Troussier, Mareva; Weyrauch, Steffen; Reemtsma, Thorsten (April 2022). “Abiotic oxidative transformation of 6-PPD and 6-PPD quinone from tires and occurrence of their products in snow from urban roads and in municipal wastewater”. Water Research. 212: 118122. Bibcode:2022WatRe.21218122S. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2022.118122. PMID 35101694. S2CID 246336931.

- Tian, Zhenyu; Zhao, Haoqi; Peter, Katherine T.; Gonzalez, Melissa; Wetzel, Jill; Wu, Christopher; Hu, Ximin; Prat, Jasmine; Mudrock, Emma; Hettinger, Rachel; Cortina, Allan E.; Biswas, Rajshree Ghosh; Kock, Flávio Vinicius Crizóstomo; Soong, Ronald; Jenne, Amy; Du, Bowen; Hou, Fan; He, Huan; Lundeen, Rachel; Gilbreath, Alicia; Sutton, Rebecca; Scholz, Nathaniel L.; Davis, Jay W.; Dodd, Michael C.; Simpson, Andre; McIntyre, Jenifer K. (3 December 2020), “A ubiquitous tire rubber–derived chemical induces acute mortality in coho salmon”, Science, 371 (6525): 185–189, doi:10.1126/science.abd6951, PMID 33273063, S2CID 227281491,

… existing TWP [tire wear particle] loading, leaching, and toxicity assessments are clearly incomplete. … Accordingly, the human health effects of such exposures merit evaluation. … It is unlikely that coho salmon are uniquely sensitive … ( in print 8 Jan 2021)

- Also an erratum to this paper published in Science vol. 375, No. 6582, 18 Feb 2022 doi:10.1126/science.abo5785 reporting the updated toxicity estimates, as referenced below.

- Zeng, Lixi; Li, Yi; Sun, Yuxin; Liu, Liang-Ying; Shen, Mingjie; Du, Bibai (31 January 2023). “Widespread Occurrence and Transport of p -Phenylenediamines and Their Quinones in Sediments across Urban Rivers, Estuaries, Coasts, and Deep-Sea Regions”. Environmental Science & Technology. 57 (6): 2393–2403. Bibcode:2023EnST…57.2393Z. doi:10.1021/acs.est.2c07652. PMID 36720114. S2CID 256458111.

- “Pollution from car tires is killing off salmon on US west coast, study finds”. The Guardian. 3 December 2020.

- “Scientists solve mystery of mass coho salmon deaths. The killer? A chemical from car tires”. Los Angeles Times. 3 December 2020.

- Johannessen, Cassandra; Helm, Paul; Lashuk, Brent; Yargeau, Viviane; Metcalfe, Chris D. (February 2022). “The Tire Wear Compounds 6PPD-Quinone and 1,3-Diphenylguanidine in an Urban Watershed”. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology. 82 (2): 171–179. doi:10.1007/s00244-021-00878-4. PMC 8335451. PMID 34347118.

- Markus Brinkmann; David Montgomery; Summer Selinger; Justin G. P. Miller; Eric Stock (2022-03-02), “Acute Toxicity of the Tire Rubber-Derived Chemical 6PPD-quinone to Four Fishes of Commercial, Cultural, and Ecological Importance”, Environmental Science & Technology Letters, vol. 9, no. 4, pp. 333–338, Bibcode:2022EnSTL…9..333B, doi:10.1021/acs.estlett.2c00050, S2CID 247336687

- Tian, Zhenyu; Gonzalez, Melissa; Rideout, Craig; Zhao, Hoaqi Nina; Hu, Ximin; Wetzel, Jill; Mudrock, Emma; James, C. Andrew; McIntyre, Jenifer K; Kolodziej, Edward P (11 January 2022), “6PPD-Quinone: Revised Toxicity Assessment and Quantification with a Commercial Standard”, Environmental Science & Technology Letters, 9 (2): 140–146, Bibcode:2022EnSTL…9..140T, doi:10.1021/acs.estlett.1c00910, S2CID 245893533

- Lena Beck (17 May 2022). “Your car is killing coho salmon”. The Counter.

- Klauschies, Toni; Isanta-Navarro, Jana (2022-07-10). “The joint effects of salt and 6PPD contamination on a freshwater herbivore” (PDF). Science of the Total Environment. 829: 154675. Bibcode:2022ScTEn.829o4675K. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.154675. PMID 35314241. S2CID 247577987 – via Dynatrait.

- Du, Bibai; Liang, Bowen; Li, Yi; Shen, Mingjie; Liu, Liang-Ying; Zeng, Lixi (13 December 2022). “First Report on the Occurrence of N -(1,3-Dimethylbutyl)- N ′-phenyl- p -phenylenediamine (6PPD) and 6PPD-Quinone as Pervasive Pollutants in Human Urine from South China”. Environmental Science & Technology Letters. 9 (12): 1056–1062. Bibcode:2022EnSTL…9.1056D. doi:10.1021/acs.estlett.2c00821. S2CID 253828438.

- Agua, Alon; Stanton, Ryan; Pirrung, Michael (2021-02-04). “Preparation of 2-((4-Methylpentan-2-Yl)amino)-5-(Phenylamino)cyclohexa-2,5-Diene-1,4-Dione (6PPD-Quinone), an Environmental Hazard for Salmon” (PDF). ChemRxiv. doi:10.26434/chemrxiv.13698985.v1. S2CID 234062284.

- Lewis, P.M. (January 1986). “Effect of ozone on rubbers: Countermeasures and unsolved problems”. Polymer Degradation and Stability. 15 (1): 33–66. doi:10.1016/0141-3910(86)90004-2.

- Cataldo, Franco (January 2018). “Early stages of p-phenylenediamine antiozonants reaction with ozone: Radical cation and nitroxyl radical formation”. Polymer Degradation and Stability. 147: 132–141. doi:10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2017.11.020.

- Choi, Sung-Seen (5 July 1997). “Migration of Antidegradants to the Surface in NR and SBR Vulcanizates”. Journal of Applied Polymer Science. 65 (1): 117–125. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4628(19970705)65:1<117::AID-APP15>3.0.CO;2-0.

- Ignatz-Hoover, Frederick; To, Byron H.; Datta, R. N.; De Hoog, Arie J.; Huntink, N. M.; Talma, A. G. (1 July 2003). “Chemical Additives Migration in Rubber”. Rubber Chemistry and Technology. 76 (3): 747–768. doi:10.5254/1.3547765.

- Cao, Guodong; Wang, Wei; Zhang, Jing; Wu, Pengfei; Zhao, Xingchen; Yang, Zhu; Hu, Di; Cai, Zongwei (5 April 2022). “New Evidence of Rubber-Derived Quinones in Water, Air, and Soil”. Environmental Science & Technology. 56 (7): 4142–4150. Bibcode:2022EnST…56.4142C. doi:10.1021/acs.est.1c07376. PMC 8988306. PMID 35316033.

- Lammintausta, K; Kalimo, K (1985). “Sensitivity to Rubber. Study with Rubber Mixes and Individual Rubber Chemicals”. Dermatosen in Beruf und Umwelt. Occupation and Environment. 33 (6): 204–8. PMID 2936592.

- Conde-Salazar, Luis; del-Río, Emilio; Guimaraens, Dolores; Domingo, Antonia González (August 1993). “Type IV Allergy to Rubber Additives: A 10-Year Study of 686 Cases”. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 29 (2): 176–180. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(93)70163-N. PMID 8335734.

- Jordan, William P. Jr. (1971-01-01). “Contact Dermatitis From N-Isopropyl-N-Phenylparaphenylenediamine: “Volkswagen Dermatitis””. Archives of Dermatology. 103 (1): 85–87. doi:10.1001/archderm.1971.04000130087014. ISSN 0003-987X.

- Zhong, Liqiao; Peng, Weijuan; Liu, Chunsheng; Gao, Lei; Chen, Daqing; Duan, Xinbin (July 2022). “IPPD-induced growth inhibition and its mechanism in zebrafish”. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety. 239: 113614. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2022.113614. PMID 35567929. S2CID 248728812.

- NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. “#0449”. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- “p-Nitroaniline”. Immediately Dangerous to Life or Health Concentrations (IDLH). National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- Booth, Gerald (2003-03-11). “Nitro Compounds, Aromatic”. In Wiley-VCH (ed.). Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry (1 ed.). Wiley. doi:10.1002/14356007.a17_411. ISBN 978-3-527-30385-4.]

- Mohrig, J.R.; Morrill, T.C.; Hammond, C.N.; Neckers, D.C. (1997). “Synthesis 5: Synthesis of the Dye Para Red from Aniline”. Experimental Organic Chemistry. New York, NY: Freeman. pp. 456–467. Archived from the original on 2020-09-15. Retrieved 2007-07-18.

- Williamson, Kenneth L. (2002). Macroscale and Microscale Organic Experiments, Fourth Edition. Houghton-Mifflin. ISBN 0-618-19702-8.

- Starkey, E. B. (1939). “p-DINITROBENZENE”. Organic Syntheses. 19: 40. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.019.0040.

- “p-NITROPHENYLARSONIC ACID”. Organic Syntheses. 26: 60. 1946. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.026.0060.

- Shriner, R. L.; Horne, W. H.; Cox, R. F. B. (1934). “p-NITROPHENYL ISOCYANATE”. Organic Syntheses. 14: 72. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.014.0072.

- “2,6-DIIODO-p-NITROANILINE”. Organic Syntheses. 12: 28. 1932. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.012.0028.

- Poshkus, A. C.; Parker, J. A. (1970). “Studies on nitroaniline–sulfuric acid compositions: Aphrogenic pyrostats”. Journal of Applied Polymer Science. 14 (8): 2049–2064. doi:10.1002/app.1970.070140813.

- Summerlin, Lee R.; Ealy, James L. (1988). “Experiment 100: Dehydration of p-Nitroaniline: Sanke and Puff”. Chemical Demonstrations: A Sourcebook for Teachers Volume 1 (2nd ed.). American Chemical Society. p. 171. ISBN 978-0-841-21481-1.

- “Carbon Snake: demonstrating the dehydration power of concentrated sulfuric acid”. communities.acs.org. 2013-06-06. Retrieved 2022-01-31.

- Making a carbon snake with P-Nitroaniline, retrieved 2022-01-31

- “4-Nitroaniline”. St. Louis, Missouri: Sigma-Aldrich. December 18, 2020.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/C-41_process

- “Ethanol, 2-((4-amino-3-methylphenyl)ethylamino)-, sulfate (1:1) (salt)”. U.S. National Center for Biotechnology Information. Retrieved 7 April 2019.

- de Groot, Anton C. (July 2013). “Side-effects of henna and semi-permanent ‘black henna’ tattoos: a full review”. Contact Dermatitis. 69 (1): 1–25. doi:10.1111/cod.12074. PMID 23782354. S2CID 140100016.

- “Temporary Tattoos & Henna/Mehndi”. Food and Drug Administration. 3 March 2022.

- Kang, Ik-Joon; Lee, Mu-Hyoung (July 2006). “Quantification of para-phenylenediamine and heavy metals in henna dye”. Contact Dermatitis. 55 (1): 26–29. doi:10.1111/j.0105-1873.2006.00845.x. PMID 16842550. S2CID 22176978.

- Dron, P; Lafourcade, MP; Leprince, F; Nonotte-Varly, C; Van Der Brempt, X; Banoun, L; Sullerot, I; This-Vaissette, C; Parisot, L; Moneret-Vautrin, DA (June 2007). “Allergies associated with body piercing and tattoos: a report of the Allergy Vigilance Network”. European Annals of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 39 (6): 189–192. PMID 17713170. S2CID 7903601.

- Raupp, P; Hassan, JA; Varughese, M; Kristiansson, B (1 November 2001). “Henna causes life threatening haemolysis in glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency”. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 85 (5): 411–412. doi:10.1136/adc.85.5.411. PMC 1718961. PMID 11668106.

- “§ 73.2190 Henna”. Listing of Color Additives Exempt from Certification. Federal Register. 30 July 2009. Archived from the original on 5 November 2009. Retrieved 3 August 2009.

- “Accessdate.fda.gov”. Accessdata.fda.gov. Retrieved 30 April 2019.

- “Dangers of black henna”. nhs.uk. 26 April 2018. Archived from the original on 8 August 2020. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- Singh, M.; Jindal, S. K.; Kavia, Z. D.; Jangid, B. L.; Khem Chand (2005). “Traditional Methods of Cultivation and Processing of Henna. Henna, Cultivation, Improvement and Trade”. Henna: Cultivation, Improvement, and Trade. Jodhpur: Central Arid Zone Research Institute. pp. 21–24. OCLC 124036118.[page needed]

- “FDA.gov”. Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 2 January 2011. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- “Rosemariearnold.com”. Archived from the original on 15 July 2011. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- Van den Keybus, C.; Morren, M.-A.; Goossens, A. (September 2005). “Walking difficulties due to an allergic reaction to a temporary tattoo”. Contact Dermatitis. 53 (3): 180–181. doi:10.1111/j.0105-1873.2005.0407m.x. PMID 16128770. S2CID 28624688.

- Stante, M; Giorgini, S; Lotti, T (April 2006). “Allergic contact dermatitis from henna temporary tattoo”. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 20 (4): 484–486. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.01483.x. PMID 16643167. S2CID 43067542.

- Jung, Peter; Sesztak-Greinecker, Gabriele; Wantke, Felix; Gotz, Manfred; Jarisch, Reinhart; Hemmer, Wolfgang (April 2006). “A painful experience: black henna tattoo causing severe, bullous contact dermatitis”. Contact Dermatitis. 54 (4): 219–220. doi:10.1111/j.0105-1873.2006.0775g.x. PMID 16650103. S2CID 43613761.

- Hassan, Inaam Bashir; Islam, Sherief I. A. M.; Alizadeh, Hussain; Kristensen, Jorgen; Kambal, Amr; Sonday, Shanaaz; Bernseen, Roos M. D. (21 July 2009). “Acute leukemia among the adult population of United Arab Emirates: an epidemiological study”. Leukemia & Lymphoma. 50 (7): 1138–1147. doi:10.1080/10428190902919184. PMID 19557635. S2CID 205701235.

- Sosted, Heidi; Johansen, Jeanne Duus; Andersen, Klaus Ejner; Menne, Torkil (February 2006). “Severe allergic hair dye reactions in 8 children”. Contact Dermatitis. 54 (2): 87–91. doi:10.1111/j.0105-1873.2006.00746.x. PMID 16487280. S2CID 39281376.

- Commission Directive 2009/134/EC of 28 October 2009 amending Council Directive 76/768/EEC concerning cosmetic products for the purposes of adapting Annex III thereto to technical progress

- Jacob, Sharon E.; Zapolanski, Tamar; Chayavichitsilp, Pamela; Connelly, Elizabeth Alvarez; Eichenfield, Lawrence F. (1 August 2008). “p-Phenylenediamine in Black Henna Tattoos”. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 162 (8): 790–2. doi:10.1001/archpedi.162.8.790. PMID 18678815.

- “Black Henna”. Florida Department of Health. 20 December 2018. Archived from the original on 29 March 2021. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- “Health Canada alerts Canadians not to use ‘black henna’ temporary tattoo ink and paste containing PPD” (Press release). Health Canada. 11 August 2003. Archived from the original on 10 June 2008.

- Avnstorp, Christian; Rastogi, Suresh C.; Menne, Torkil (August 2002). “Acute fingertip dermatitis from a temporary tattoo and quantitative chemical analysis of the product”. Contact Dermatitis. 47 (2): 109–125. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0536.2002.470210_11.x. PMID 12455547. S2CID 34550567.

- Marcoux, Danielle; Couture‐Trudel, Pierre‐Marc; Riboulet‐Delmas, Gisèle; Sasseville, Denis (23 November 2002). “Sensitization to Para‐Phenylenediamine from a Streetside Temporary Tattoo”. Pediatric Dermatology. 19 (6): 498–502. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1470.2002.00218.x. PMID 12437549. S2CID 23543707.

- Onder, M (July 2003). “Temporary holiday ‘tattoos’ may cause lifelong allergic contact dermatitis when henna is mixed with PPD”. Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology. 2 (3–4): 126–130. doi:10.1111/j.1473-2130.2004.00083.x. PMID 17163917. S2CID 38957088.

- Onder, Meltem; Atahan, Cigdem Asena; Oztas, Pinar; Oztas, Murat Orhan (September 2001). “Temporary henna tattoo reactions in children”. International Journal of Dermatology. 40 (9): 577–579. doi:10.1046/j.1365-4362.2001.01248.x. PMID 11737452. S2CID 221816034.

- “PPD In ‘Black Henna’ Temporary Tattoos Is Not Safe”. Health Canada. 16 December 2008. Archived from the original on 24 April 2010. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- Moro, Paola; Morina, Marco; Milani, Fabrizia; Pandolfi, Marco; Guerriero, Francesca; Bernardo, Luca (11 July 2016). “Sensitization and Clinically Relevant Allergy to Hair Dyes and Clothes from Black Henna Tattoos: Do People Know the Risk? An Uncommon Serious Case and a Review of the Literature”. Cosmetics. 3 (3): 23. doi:10.3390/cosmetics3030023. ISSN 2079-9284.

- Ahmadjian, Vernon; Hale, Mason E. (1973). The Lichens. New York: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-044950-7. pp. 636–637.

- Dahl, Eilif; Krog, Hildur (1973). Macrolichens of Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden. Universitetsforlaget. ISBN 9788200022626. p. 23.

- Sharnoff, Stephen (2014). A Field Guide to California Lichens. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 369–371. ISBN 978-0-300-19500-2. OCLC 862053107.

- Le Pogam, Pierre; Herbette, Gaëtan; Boustie, Joël (19 December 2014). “Analysis of Lichen Metabolites, a Variety of Approaches”. Recent Advances in Lichenology. New Delhi: Springer India. pp. 229–261. doi:10.1007/978-81-322-2181-4_11. ISBN 978-81-322-2180-7.

Leave a Reply