Perivitellin-2 (PV2) is a pore-forming toxin present in the egg perivitelline fluid of the apple snails Pomacea maculata (PmPV2) and Pomacea canaliculata (PcPV2). This protein, called perivitellin, is massively accumulated in the eggs (~20 % total protein). As a toxin PV2 protects eggs from predators, but it also nourishes the developing snail embryos.

- Giglio ML, Ituarte S, Ibañez AE, Dreon MS, Prieto E, Fernández PE, Heras H (2020). “Novel Role for Animal Innate Immune Molecules: Enterotoxic Activity of a Snail Egg MACPF-Toxin”. Frontiers in Immunology. 11: 428. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2020.00428. PMC 7082926. PMID 32231667.

Structure and stability

These ~172-kDa proteins are dimers of AB toxins, each composed of a carbohydrate-binding protein of the tachylectin family (targeting module) disulfide-linked to a pore-forming protein of the Membrane Attack Complex and Perforin (MACPF) family (toxic unit). Like most other studied perivitellins from Pomacea snails, PV2s are highly stable in a wide range of pH values and withstand gastrointestinal digestion, characteristics associated with an antinutritive defense system that deters predation by lowering the nutritional value of the eggs.

- Giglio ML, Ituarte S, Ibañez AE, Dreon MS, Prieto E, Fernández PE, Heras H (2020). “Novel Role for Animal Innate Immune Molecules: Enterotoxic Activity of a Snail Egg MACPF-Toxin”. Frontiers in Immunology. 11: 428. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2020.00428. PMC 7082926. PMID 32231667.

- Dreon MS, Frassa MV, Ceolín M, Ituarte S, Qiu JW, Sun J, et al. (2013-05-30). “Novel animal defenses against predation: a snail egg neurotoxin combining lectin and pore-forming chains that resembles plant defense and bacteria attack toxins”. PLOS ONE. 8 (5): e63782. Bibcode:2013PLoSO…863782D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0063782. PMC 3667788. PMID 23737950.

- Giglio ML, Ituarte S, Milesi V, Dreon MS, Brola TR, Caramelo J, et al. (August 2020). “Exaptation of two ancient immune proteins into a new dimeric pore-forming toxin in snails”. Journal of Structural Biology. 211 (2): 107531. doi:10.1016/j.jsb.2020.107531. hdl:11336/143650. PMID 32446810. S2CID 218873723

- Frassa MV, Ceolín M, Dreon MS, Heras H (July 2010). “Structure and stability of the neurotoxin PV2 from the eggs of the apple snail Pomacea canaliculata”. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) – Proteins and Proteomics. 1804 (7): 1492–1499. doi:10.1016/j.bbapap.2010.02.013. PMID 20215051.

Functions

As part of the perivitelline fluid, perivitellin-2 constitutes a nutrient source for the developing embryo, notably in the last stages where it is probably used as an endogenous source of energy and structural molecules during the transition to the free life. PV2s also play a role in a complex defense system that protects the embryos against predation.

- Giglio ML, Ituarte S, Ibañez AE, Dreon MS, Prieto E, Fernández PE, Heras H (2020). “Novel Role for Animal Innate Immune Molecules: Enterotoxic Activity of a Snail Egg MACPF-Toxin”. Frontiers in Immunology. 11: 428. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2020.00428. PMC 7082926. PMID 32231667.

- Dreon MS, Frassa MV, Ceolín M, Ituarte S, Qiu JW, Sun J, et al. (2013-05-30). “Novel animal defenses against predation: a snail egg neurotoxin combining lectin and pore-forming chains that resembles plant defense and bacteria attack toxins”. PLOS ONE. 8 (5): e63782. Bibcode:2013PLoSO…863782D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0063782. PMC 3667788. PMID 23737950.

- Heras H, Garin CF, Pollero RJ (1998). “Biochemical composition and energy sources during embryo development and in early juveniles of the snail Pomacea canaliculata (Mollusca: Gastropoda)”. Journal of Experimental Zoology. 280 (6): 375–383. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-010X(19980415)280:6<375::AID-JEZ1>3.0.CO;2-K. ISSN 1097-010X.

- Heras H, Frassa MV, Fernández PE, Galosi CM, Gimeno EJ, Dreon MS (September 2008). “First egg protein with a neurotoxic effect on mice”. Toxicon. 52 (3): 481–488. doi:10.1016/j.toxicon.2008.06.022. PMID 18640143.

PV2s have both lectin and perforin activities, associated to the two subunits of their particular structures. As a lectin, PV2s can agglutinate rabbit red blood cells and bind to the plasma membrane of intestinal cells both in vitro and in vivo. As a perforin, PV2s are able to disrupt intestinal cells altering the plasma membrane conductance and to form large pores in artificial lipid bilayers. An interesting issue with these perivitellins is that the combination of two immune proteins (lectin and perforin) gave rise to a new toxic entity, an excellent example of protein exaptation. This binary structure includes PV2s within “AB-toxins”, a group of toxins mostly described in bacteria and plants. In PV2 toxins, the lectin would bind to target membranes through the recognition of specific glycans, acting as a delivery “B” subunit, and then the pore-forming “A” subunit would disrupt lipid bilayers forming large pores and leading to cell death, therefore constituting a true pore-forming toxin.

- Giglio ML, Ituarte S, Ibañez AE, Dreon MS, Prieto E, Fernández PE, Heras H (2020). “Novel Role for Animal Innate Immune Molecules: Enterotoxic Activity of a Snail Egg MACPF-Toxin”. Frontiers in Immunology. 11: 428. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2020.00428. PMC 7082926. PMID 32231667.

- Dreon MS, Frassa MV, Ceolín M, Ituarte S, Qiu JW, Sun J, et al. (2013-05-30). “Novel animal defenses against predation: a snail egg neurotoxin combining lectin and pore-forming chains that resembles plant defense and bacteria attack toxins”. PLOS ONE. 8 (5): e63782. Bibcode:2013PLoSO…863782D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0063782. PMC 3667788. PMID 23737950.

- Giglio ML, Ituarte S, Milesi V, Dreon MS, Brola TR, Caramelo J, et al. (August 2020). “Exaptation of two ancient immune proteins into a new dimeric pore-forming toxin in snails”. Journal of Structural Biology. 211 (2): 107531. doi:10.1016/j.jsb.2020.107531. hdl:11336/143650. PMID 32446810. S2CID 218873723

- Dreon MS, Fernández PE, Gimeno EJ, Heras H (June 2014). “Insights into embryo defenses of the invasive apple snail Pomacea canaliculata: egg mass ingestion affects rat intestine morphology and growth”. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 8 (6): e2961. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0002961. PMC 4063725. PMID 24945629

Toxicity toward mammals

PV2 toxins proved to be highly toxic to mice when it enters the bloodstream (LD50, 96 h 0.25 mg/kg, i.p.) and those receiving sublethal doses displayed neurological signs including weakness and lethargy, low head and bent down position (ortopneic), half-closed eyes, taquipnea, hirsute hair, extreme abduction of the rear limbs, paresia and were not able to support their body weight (tetraplegic), among others. Histopathological analyses of affected mice showed that PV2 toxins affect the dorsal horn of the spinal cord, particularly on the 2nd and 3rd gray matter laminas, where alters the calcium metabolism and causes neuron apoptosis. Apart from its neurotoxicity, it has been recently shown that PV2s are also enterotoxic to mice when ingested, a function that had never been ascribed to animal proteins. At the cellular level, PV2 is cytotoxic to intestinal cells, on which it causes changes in their surface morphology increasing the membrane roughness. At the system level, oral administration of PV2 induces large morphological changes on mice intestine mucosa, reducing its absorptive surface. Additionally, PV2 reaches the Peyer’s patches where it activates lymphoid follicles and triggers apoptosis.

- Giglio ML, Ituarte S, Ibañez AE, Dreon MS, Prieto E, Fernández PE, Heras H (2020). “Novel Role for Animal Innate Immune Molecules: Enterotoxic Activity of a Snail Egg MACPF-Toxin”. Frontiers in Immunology. 11: 428. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2020.00428. PMC 7082926. PMID 32231667.

- Giglio ML, Ituarte S, Milesi V, Dreon MS, Brola TR, Caramelo J, et al. (August 2020). “Exaptation of two ancient immune proteins into a new dimeric pore-forming toxin in snails”. Journal of Structural Biology. 211 (2): 107531. doi:10.1016/j.jsb.2020.107531. hdl:11336/143650. PMID 32446810. S2CID 218873723

- Heras H, Frassa MV, Fernández PE, Galosi CM, Gimeno EJ, Dreon MS (September 2008). “First egg protein with a neurotoxic effect on mice”. Toxicon. 52 (3): 481–488. doi:10.1016/j.toxicon.2008.06.022. PMID 18640143.

Peyer’s patches (or aggregated lymphoid nodules) are organized lymphoid follicles, named after the 17th-century Swiss anatomist Johann Conrad Peyer. They are an important part of gut associated lymphoid tissue usually found in humans in the lowest portion of the small intestine, mainly in the distal jejunum and the ileum, but also could be detected in the duodenum. Peyer’s patches had been observed and described by several anatomists during the 17th century, but in 1677 Swiss anatomist Johann Conrad Peyer (1653–1712) described the patches so clearly that they were eventually named after him. However, Peyer regarded them as glands which discharged, into the small intestine, some substance which facilitated digestion. It was not until 1850 that the Swiss physician Rudolph Oskar Ziegler (1828–1881) suggested, after careful microscopic examination, that Peyer’s patches were actually lymph glands.

- Peyer, Johann Conrad (1677). Exercitatio Anatomico-Medica de Glandulis Intestinorum, Earumque Usu et Affectionibus [Anatomical-medical essay on the intestinal glands, and their function and diseases] (in Latin). Schaffhausen, Switzerland: Onophrius à Waldkirch.

- Reprinted as: Peyer, Johann Conrad (1681). Exercitatio Anatomico-Medica de Glandulis Intestinorum, Earumque Usu et Affectionibus (in Latin). Amsterdam, Netherlands: Henrik Wetstein.

- Peyer referred to Peyer’s patches as plexus or agmina glandularum (clusters of glands). From (Peyer, 1681), p. 7: “Tenui a perfectiorum animalium Intestina accuratius perlustranti, crebra hinc inde, variis intervallis, corpusculorum glandulosorum Agmina sive Plexus se produnt, diversae Magnitudinis atque Figurae.” (I knew from careful study of more advanced animals, the intestines bear — often here and there, at various intervals — clusters of glandular small bodies or “plexuses” of diverse size and shape.) From p. 15: “(has Plexus seu agmina Glandularum voco)” (I call them “plexuses” or clusters of glands) He described their appearance. From p. 8: “Horum vero Plexuum facies modo in orbem concinnata; modo in Ovi aut Olivae oblongam, aliamve angulosam ac magis anomalam disposita figuram cernitur.” (But the configurations of these “plexuses” are arranged at one time in a circle; at another time, it is seen in an egg [shape] or an oblong olive [shape] or other faceted and more irregularly arranged shape.) Drawings of Peyer’s patches appear after pages 22 and 24.

- M, Auchincloss H, Loring JM, Chase CM, Russell PS, Jaenisch R (April 1992). “Skin graft rejection by beta 2-microglobulin-deficient mice”. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 175 (4): 885–93. doi:10.1136/gut.6.3.225. PMC 1552287. PMID 18668776.

- Haller, Albrecht von (1765). Elementa Physiologiae corporis humani [Elements of the physiology of the human body] (in Latin). Vol. 7. Bern, Switzerland: Societas Typographica. p. 35. Anatomists who mentioned Peyer’s patches included:

- Johann Theodor Schenck (1619–1671): Schenck, Johann Theodor (1672). Exercitationes Anatomicæ ad Usum Medicum Accommodatæ [Anatomical Exercises Suited to Medical Practice] (in Latin). Jena, (Germany): Johann Ludwig Neuenhahn. p. 334. Schenk thought that intestinal worms resided in Peyer’s patches and that the orifices of the patches were the worms’ mouths. From p. 334: “In canibus saepissime observavi non ad ventriculum … a praeter labente chylo sibi conveniens allicerent.” (In dogs, I very often noticed — not only near the stomach but also on the walls of their small intestines — flesh-colored or glandular blisters, [appearing] to swim one after another, [in] which, when we dissected [them], I observed some smooth reddish worms [vermium] living there in clusters [with] their heads facing towards the cavity of the intestines, in which part there were glands with orifices, [but] reversed, so that from there they obtained, from the chyle flowing past, nourishment [that was] suitable for them.)

- Jeremias Loss (1643–1684): Loss, Jeremias (1683). Dissertatio Medica de Glandulis in Genere [Medical Discourse on Glands in [Various] Species] (in Latin). Wittenberg, (Germany): Martin Schultz. p. 12. On page 12, Loss states that some glands are located “inter Membranas viscerum quorundam” (between the membranes of certain internal organs) ” … prout id in Glandulis Intestinorum satis manifestum est.” (as it is quite clear in the glands of the intestines), where “In Intestinis ita congregantur, interdum pauciores, interdum plures, ut areolas quasdam constituant: … ” (in the intestines there are thus gathered sometimes fewer [glands], sometimes more [glands], so that they form certain round patches.)

- Johannes Nicolaus Pechlin (1646–1706): Pechlin, Johannes Nicolaus (1672). De Purgantium Medicamentorum Facultatibus [On the Means of Medicinal Purges] (in Latin). Leiden and Amsterdam, Netherlands: Daniel, Abraham, and Adrian à Gaasbeek. p. 510. From p. 510: ” … ego tenuium glandularum glomeratum agmen esse ratus, … ” (… I considered the heaped cluster of fine glands, … )

- Martin Lister (ca. 1638–1712): Lister, Martin (23 June 1673). “A letter of Mr Lister dated May 21. 1673. in York, partly taking notice of the foregoing intimations, partly communicating some anatomical observations and experiments concerning the unalterable character of the whiteness of the chyle within the lacteous veins; together with divers particulars observed in the guts, especially several sorts of worms found in them”. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 8 (95): 6060–6065. Bibcode:1673RSPT….8.6060L. doi:10.1098/rstl.1673.0026. From p. 6062: “As 1. Glandulae miliares of the small Guts, which may also in some Animals be well call’d fragi-formes, from the figure of the one half of a Strawberry, and which yet I take to be Excretive glanduls, because Conglomerate.”

- Nehemiah Grew (1641–1712): Grew, Nehemiah (1681). The Comparative Anatomy of Stomachs and Guts Begun. Being Several Lectures Read before the Royal Society. In the Year, 1676. London, England: Self-published. p. 3. Grew called Peyer’s patches pancreas intestinale.

- There were many earlier names for Peyer’s patches:

- Todd, Robert Bentley, ed. (1859). The Cyclopædia of Anatomy and Physiology. Vol. 5. London, England: Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans, & Roberts. p. 356 footnote.

- Leidy, Joseph (1861). An Elementary Treatise on Human Anatomy. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA: J.B. Lippincott & Co. p. 313 footnote.

- Ziegler, Rudolph Oskar (1850) Ueber die solitären und Peyerschen Follikel : Inaugural-Abhandlung, der medicinischen Facultät der Julius-Maximilians-Universität zu Würzburg vorgelegt [On solitary and Peyer’s follicles: Inaugural treatise, submitted to the medical faculty of the Julius-Maximilians-University of Würzburg] (in German) Würzburg, (Germany): Friederich Ernst Thein. From p. 37: “Ebensogross, wo nicht grösser ist die Aehnlichkeit der sogenannten Peyer’schen Drüsen und der Lymphdrüsen.” (Just as great, if not greater, is the resemblance between the so-called Peyer’s glands and the lymph glands.) From p. 38: ” … ja, man könnte selbst versucht sein, die letzteren für nichts als eine Art von zwischen den Wänden der Darmsschleimhaut eingebetteten Lymphdrüsen zu halten.” ( … indeed, one could even be tempted to regard the latter [i.e., the Peyer’s patches] as nothing but some type of lymph glands [which are] embedded between the walls of the intestinal mucosa.)

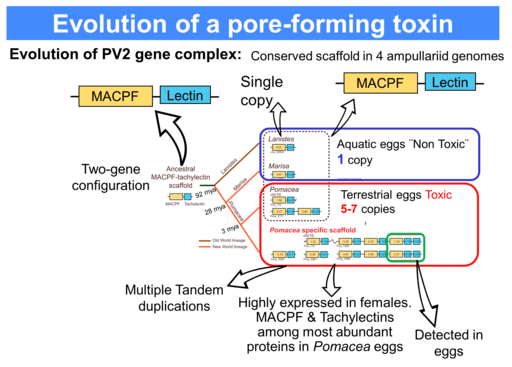

Evolution of a pore-forming toxin

Proteomic analysis indicates that the MACPF and the Tachylectins are among the most abundant proteins in Pomacea eggs but are minor proteins in the genera laying eggs below the water. According to the fossil record, some 3 MYA, when Pomacea diverged from Marisa and began laying eggs above the water, these two genes were subjected to extensive duplication and these unrelated proteins were combined by a covalent bond resulting in the dimerization into PV2 AB toxin that co-opted to new roles. This new structure rendered a novel toxin that is non-digestible, enterotoxic and neurotoxic.

- Giglio ML, Ituarte S, Ibañez AE, Dreon MS, Prieto E, Fernández PE, Heras H (2020). “Novel Role for Animal Innate Immune Molecules: Enterotoxic Activity of a Snail Egg MACPF-Toxin”. Frontiers in Immunology. 11: 428. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2020.00428. PMC 7082926. PMID 32231667.

- Giglio ML, Ituarte S, Milesi V, Dreon MS, Brola TR, Caramelo J, et al. (August 2020). “Exaptation of two ancient immune proteins into a new dimeric pore-forming toxin in snails”. Journal of Structural Biology. 211 (2): 107531. doi:10.1016/j.jsb.2020.107531. hdl:11336/143650. PMID 32446810. S2CID 218873723

- Sun J, Zhang H, Wang H, Heras H, Dreon MS, Ituarte S, et al. (August 2012). “First proteome of the egg perivitelline fluid of a freshwater gastropod with aerial oviposition”. Journal of Proteome Research. 11 (8): 4240–4248. doi:10.1021/pr3003613. hdl:11336/94414. PMID 22738194.

- Mu H, Sun J, Heras H, Chu KH, Qiu JW (February 2017). “An integrated proteomic and transcriptomic analysis of perivitelline fluid proteins in a freshwater gastropod laying aerial eggs”. Journal of Proteomics. 155: 22–30. doi:10.1016/j.jprot.2017.01.006. PMID 28095328. S2CID 19632393.

References

- Giglio ML, Ituarte S, Ibañez AE, Dreon MS, Prieto E, Fernández PE, Heras H (2020). “Novel Role for Animal Innate Immune Molecules: Enterotoxic Activity of a Snail Egg MACPF-Toxin”. Frontiers in Immunology. 11: 428. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2020.00428. PMC 7082926. PMID 32231667.

- Dreon MS, Frassa MV, Ceolín M, Ituarte S, Qiu JW, Sun J, et al. (2013-05-30). “Novel animal defenses against predation: a snail egg neurotoxin combining lectin and pore-forming chains that resembles plant defense and bacteria attack toxins”. PLOS ONE. 8 (5): e63782. Bibcode:2013PLoSO…863782D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0063782. PMC 3667788. PMID 23737950.

- Giglio ML, Ituarte S, Milesi V, Dreon MS, Brola TR, Caramelo J, et al. (August 2020). “Exaptation of two ancient immune proteins into a new dimeric pore-forming toxin in snails”. Journal of Structural Biology. 211 (2): 107531. doi:10.1016/j.jsb.2020.107531. hdl:11336/143650. PMID 32446810. S2CID 218873723

- Frassa MV, Ceolín M, Dreon MS, Heras H (July 2010). “Structure and stability of the neurotoxin PV2 from the eggs of the apple snail Pomacea canaliculata”. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) – Proteins and Proteomics. 1804 (7): 1492–1499. doi:10.1016/j.bbapap.2010.02.013. PMID 20215051.

- Heras H, Garin CF, Pollero RJ (1998). “Biochemical composition and energy sources during embryo development and in early juveniles of the snail Pomacea canaliculata (Mollusca: Gastropoda)”. Journal of Experimental Zoology. 280 (6): 375–383. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-010X(19980415)280:6<375::AID-JEZ1>3.0.CO;2-K. ISSN 1097-010X.

- Heras H, Frassa MV, Fernández PE, Galosi CM, Gimeno EJ, Dreon MS (September 2008). “First egg protein with a neurotoxic effect on mice”. Toxicon. 52 (3): 481–488. doi:10.1016/j.toxicon.2008.06.022. PMID 18640143.

- Dreon MS, Fernández PE, Gimeno EJ, Heras H (June 2014). “Insights into embryo defenses of the invasive apple snail Pomacea canaliculata: egg mass ingestion affects rat intestine morphology and growth”. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 8 (6): e2961. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0002961. PMC 4063725. PMID 24945629.

- Sun J, Mu H, Ip JC, Li R, Xu T, Accorsi A, et al. (July 2019). Russo C (ed.). “Signatures of Divergence, Invasiveness, and Terrestrialization Revealed by Four Apple Snail Genomes”. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 36 (7): 1507–1520. doi:10.1093/molbev/msz084. PMC 6573481. PMID 30980073.

- Sun J, Zhang H, Wang H, Heras H, Dreon MS, Ituarte S, et al. (August 2012). “First proteome of the egg perivitelline fluid of a freshwater gastropod with aerial oviposition”. Journal of Proteome Research. 11 (8): 4240–4248. doi:10.1021/pr3003613. hdl:11336/94414. PMID 22738194.

- Mu H, Sun J, Heras H, Chu KH, Qiu JW (February 2017). “An integrated proteomic and transcriptomic analysis of perivitelline fluid proteins in a freshwater gastropod laying aerial eggs”. Journal of Proteomics. 155: 22–30. doi:10.1016/j.jprot.2017.01.006. PMID 28095328. S2CID 19632393.

Leave a Reply