Pelger–Huët anomaly, congenital and acquired, also pince-nez, laminopathy and a little ebola

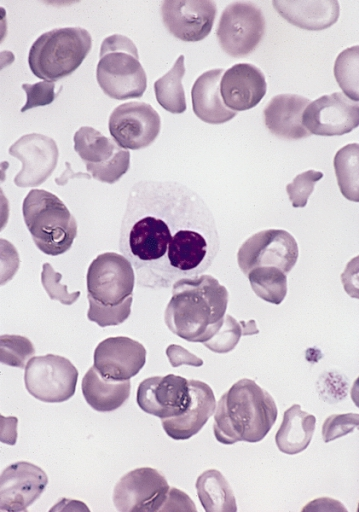

Pelger–Huët anomaly is a blood laminopathy associated with the lamin B receptor, wherein several types of white blood cells (neutrophils and eosinophils) have nuclei with unusual shape (being bilobed, peanut or dumbbell-shaped instead of the normal trilobed shape) and unusual structure (coarse and lumpy). It is a genetic disorder with an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern. Heterozygotes are clinically normal, although their neutrophils may be mistaken for immature cells which may cause mistreatment in a clinical setting. Homozygotes tend to have neutrophils with rounded nuclei that do have some functional problems.[citation needed]

- Hoffmann, Katrin; Dreger, Christine K.; Olins, Ada L.; Olins, Donald E.; Shultz, Leonard D.; Lucke, Barbara; Karl, Hartmut; Kaps, Reinhard; Müller, Dietmar; Vayá, Amparo; Aznar, Justo; Ware, Russell E.; Cruz, Norberto Sotelo; Lindner, Tom H.; Herrmann, Harald; Reis, André; Sperling, Karl (2002). “Mutations in the gene encoding the lamin B receptor produce an altered nuclear morphology in granulocytes (Pelger–Huët anomaly)”. Nature Genetics. 31 (4): 410–4. doi:10.1038/ng925. PMID 12118250. S2CID 6020153.

- “Pelger-Huet anomaly”. Disease Infosearch. Retrieved 2020-04-27. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License

Laminopathies are a group of rare genetic disorders caused by mutations in genes encoding proteins of the nuclear lamina. They are included in the more generic term nuclear envelopathies that was coined in 2000 for diseases associated with defects of the nuclear envelope. Since the first reports of laminopathies in the late 1990s, increased research efforts have started to uncover the vital role of nuclear envelope proteins in cell and tissue integrity in animals.

- Paradisi M, McClintock D, Boguslavsky RL, Pedicelli C, Worman HJ, Djabali K (2005). “Dermal fibroblasts in Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome with the lamin A G608G mutation have dysmorphic nuclei and are hypersensitive to heat stress”. BMC Cell Biol. 6: 27. doi:10.1186/1471-2121-6-27. PMC 1183198. PMID 15982412.

- Nagano A, Arahata K (2000). “Nuclear envelope proteins and associated diseases”. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 13 (5): 533–9. doi:10.1097/00019052-200010000-00005. PMID 11073359. S2CID 12550140.

Laminopathies and other nuclear envelopathies have a large variety of clinical symptoms including skeletal and/or cardiac muscular dystrophy, lipodystrophy and diabetes, dysplasia, dermo- or neuropathy, leukodystrophy, and progeria (premature aging). Most of these symptoms develop after birth, typically during childhood or adolescence. Some laminopathies however may lead to an early death, and mutations of lamin B1 (LMNB1 gene) may be lethal before or at birth. Patients with classical laminopathy have mutations in the gene coding for lamin A/C (LMNA gene).[citation needed]

- Vergnes L, Peterfy M, Bergo MO, Young SG, Reue K (2004). “Lamin B1 is required for mouse development and nuclear integrity”. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101 (28): 10428–33. Bibcode:2004PNAS..10110428V. doi:10.1073/pnas.0401424101. PMC 478588. PMID 15232008.

Mutations in the gene coding for lamin B2 (LMNB2 gene) have been linked to Barraquer-Simons syndrome and duplication in the gene coding for lamin B1 (LMNB1 gene) cause autosomal dominant leukodystrophy. Mutations implicated in other nuclear envelopathies were found in genes coding for lamin-binding proteins such as lamin B receptor (LBR gene), emerin (EMD gene) and LEM domain-containing protein 3 (LEMD3 gene) and prelamin A-processing enzymes such as the zinc metalloproteinase STE24 (ZMPSTE24 gene). Mutations causing laminopathies include recessive as well as dominant alleles with rare de novo mutations creating dominant alleles that do not allow their carriers to reproduce before death.[citation needed] The nuclear envelopathy with the highest frequency in human populations is Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophy caused by an X-linked mutation in the EMD gene coding for emerin and affecting an estimated 1 in 100,000 people.[citation needed]

- Hegele RA, Cao H, Liu DM, Costain GA, Charlton-Menys V, Rodger NW, Durrington PN (2006). “Sequencing of the reannotated LMNB2 gene reveals novel mutations in patients with acquired partial lipodystrophy”. Am J Hum Genet. 79 (2): 383–389. doi:10.1086/505885. PMC 1559499. PMID 16826530.

- Padiath QS, Saigoh K, Schiffmann R, Asahara H, Yamada T, Koeppen A, Hogan K, Ptácek LJ, Fu YH (2006). “Lamin B1 duplications cause autosomal dominant leukodystrophy”. Nat Genet. 38 (10): 1114–1123. doi:10.1038/ng1872. PMID 16951681. S2CID 25336497.

- Hoffmann, Katrin; Dreger, Christine K.; Olins, Ada L.; Olins, Donald E.; Shultz, Leonard D.; Lucke, Barbara; Karl, Hartmut; Kaps, Reinhard; Müller, Dietmar; Vayá, Amparo; Aznar, Justo (2002-07-15). “Mutations in the gene encoding the lamin B receptor produce an altered nuclear morphology in granulocytes (Pelger–Huët anomaly)”. Nature Genetics. 31 (4): 410–414. doi:10.1038/ng925. ISSN 1061-4036. PMID 12118250. S2CID 6020153.

- Waterham, Hans R.; Koster, Janet; Mooyer, Petra; Noort, Gerard van; Kelley, Richard I.; Wilcox, William R.; Ronald Wanders, J.A.; Raoul Hennekam, C.M.; Jan Oosterwijk, C. (April 2003). “Autosomal Recessive HEM/Greenberg Skeletal Dysplasia Is Caused by 3β-Hydroxysterol Δ14-Reductase Deficiency Due to Mutations in the Lamin B Receptor Gene”. The American Journal of Human Genetics. 72 (4): 1013–1017. doi:10.1086/373938. ISSN 0002-9297. PMC 1180330. PMID 12618959.

- Greenberg, Cheryl R.; Rimoin, David L.; Gruber, Helen E.; DeSa, D. J. B.; Reed, M.; Lachman, Ralph S.; Optiz, John M.; Reynolds, James F. (March 1988). “A new autosomal recessive lethal chondrodystrophy with congenital hydrops”. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 29 (3): 623–632. doi:10.1002/ajmg.1320290321. ISSN 0148-7299. PMID 3377005.

- Shultz, L. D. (2003-01-01). “Mutations at the mouse ichthyosis locus are within the lamin B receptor gene: a single gene model for human Pelger-Huet anomaly”. Human Molecular Genetics. 12 (1): 61–69. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddg003. ISSN 1460-2083. PMID 12490533.

- Young, Alexander Neil; Perlas, Emerald; Ruiz-Blanes, Nerea; Hierholzer, Andreas; Pomella, Nicola; Martin-Martin, Belen; Liverziani, Alessandra; Jachowicz, Joanna W.; Giannakouros, Thomas; Cerase, Andrea (2021-04-12). “Deletion of LBR N-terminal domains recapitulates Pelger-Huet anomaly phenotypes in mouse without disrupting X chromosome inactivation”. Communications Biology. 4 (1): 478. doi:10.1038/s42003-021-01944-2. ISSN 2399-3642. PMC 8041748. PMID 33846535.

Types of known laminopathies and other nuclear envelopathies

| Syndrome | OMIM ID | Symptoms | Mutation in | Identified in |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atypical Werner syndrome | 277700 | Progeria with increased severity compared to normal Werner syndrome | Lamin A/C | 2003 |

| Barraquer–Simons syndrome | 608709 | Lipodystrophy | Lamin B2 | 2006 |

| Buschke–Ollendorff syndrome | 166700 | Skeletal dysplasia, skin lesions | LEM domain containing protein 3 (lamin-binding protein) | 2004 |

| Cardiomyopathy, dilated, with quadriceps myopathy | 607920 | Cardiomyopathy | Lamin A/C | 2003[ |

| Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease, axonal, type 2B1 | 605588 | Neuropathy | Lamin A/C | 2002 |

| Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophy, X-linked (EDMD) | 310300 | Skeletal and cardiac muscular dystrophy | Emerin (lamin-binding protein) | 1996, 2000 |

| Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophy, autosomal dominant (EDMD2) | 181350 | Skeletal and cardiac muscular dystrophy | Lamin A/C | 1999 |

| Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophy, autosomal recessive (EDMD3) | 604929 | Skeletal and cardiac muscular dystrophy | Lamin A/C | 2000 |

| Familial partial lipodystrophy of the Dunnigan type (FPLD) | 151660 | Lipoatrophic diabetes | Lamin A/C | 2002 |

| Greenberg dysplasia | 215140 | Skeletal dysplasia | Lamin B receptor | 2003 |

| Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome (HGPS) | 176670 | Progeria | Lamin A/C | 2003 |

| Leukodystrophy, demyelinating, adult-onset, autosomal dominant (ADLD) | 169500 | Progressive demyelinating disorder affecting the central nervous system | Lamin B1 (tandem gene duplication) | 2006 |

| Limb-girdle muscular dystrophy type 1B (LGMD1B) | 159001 | Muscular dystrophy of hips and shoulders, cardiomyopathy | Lamin A/C | 2000 |

| Lipoatrophy with diabetes, hepatic steatosis, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and leukomelanodermic papules (LDHCP) | 608056 | Lipoatrophic diabetes, fatty liver, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, skin lesions | Lamin A/C | 2003 |

| Mandibuloacral dysplasia with type A lipodystrophy (MADA) | 248370 | Dysplasia and lipodystrophy | Lamin A/C | 2002 |

| Mandibuloacral dysplasia with type B lipodystrophy (MADB) | 608612 | Dysplasia and lipodystrophy | Zinc metalloprotease STE24 (prelamin-processing enzyme) | 2003 |

| Pelger–Huet anomaly (PHA) | 169400 | Myelodysplasia | Lamin B receptor | 2002 |

| Restrictive dermopathy, lethal | 275210 | Dermopathy | Lamin A/C or Zinc metalloprotease STE24 (prelamin-processing enzyme) | 2004 |

Currently, there is no cure for laminopathies and treatment is largely symptomatic and supportive. Physical therapy and/or corrective orthopedic surgery may be helpful for patients with muscular dystrophies. Laminopathies affecting heart muscle may cause heart failure requiring treatment with medications including ACE inhibitors, beta blockers and aldosterone antagonists, while the abnormal heart rhythms that frequently occur in these patients may require a pacemaker or implantable defibrillator. Treatment for neuropathies may include medication for seizures and spasticity.[citation needed]

- Captur, Gabriella; Arbustini, Eloisa; Bonne, Gisèle; Syrris, Petros; Mills, Kevin; Wahbi, Karim; Mohiddin, Saidi A.; McKenna, William J.; Pettit, Stephen (2017-11-25). “Lamin and the heart” (PDF). Heart. 104 (6): 468–479. doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2017-312338. ISSN 1468-201X. PMID 29175975. S2CID 3563474.

The recent progress in uncovering the molecular mechanisms of toxic progerin formation in laminopathies leading to premature aging has opened up the potential for the development of targeted treatment. The farnesylation of prelamin A and its pathological form progerin is carried out by the enzyme farnesyl transferase. Farnesyl transferase inhibitors (FTIs) can be used effectively to reduce symptoms in two mouse model systems for progeria and to revert the abnormal nuclear morphology in progeroid cell cultures. Two oral FTIs, lonafarnib and tipifarnib, are already in use as anti-tumor medication in humans and may become avenues of treatment for children with laminopathic progeria. Nitrogen-containing bisphosphate drugs used in the treatment of osteoporosis reduce farnesyldiphosphate production and thus prelamin A farnesylation. Testing of these drugs may prove them to be useful in treating progeria as well. The use of antisense oligonucleotides to inhibit progerin synthesis in affected cells is another avenue of current research into the development of anti-progerin drugs.

- Rusinal AE, Sinensky MS (2006). “Farnesylated lamins, progeroid syndromes and farnesyl transferase inhibitors”. J. Cell Sci. 119 (Pt 16): 3265–72. doi:10.1242/jcs.03156. PMID 16899817.

- Meta M, Yang SH, Bergo MO, Fong LG, Young SG (2006). “Protein farnesyltransferase inhibitors and progeria”. Trends Mol. Med. 12 (10): 480–7. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2006.08.006. PMID 16942914.

Congenital Pelger–Huët anomaly

Is a benign dominantly inherited defect of terminal neutrophil differentiation as a result of mutations in the lamin B receptor gene. The characteristic leukocyte appearance was first reported in 1928 by Karel Pelger (1885-1931), a Dutch Hematologist, who described leukocytes with dumbbell-shaped bilobed nuclei, a reduced number of nuclear segments, and coarse clumping of the nuclear chromatin. In 1931, Gauthier Jean Huet (1879-1970), a Dutch Pediatrician, identified it as an inherited disorder.

- Cunningham, John M.; Patnaik, Mrinal M.; Hammerschmidt, Dale E.; Vercellotti, Gregory M. (2009). “Historical perspective and clinical implications of the Pelger-Huet cell”. American Journal of Hematology. 84 (2): 116–9. doi:10.1002/ajh.21320. PMID 19021122.

It is a genetic disorder with an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern. Heterozygotes are clinically normal, although their neutrophils may be mistaken for immature cells, which may cause mistreatment in a clinical setting. Homozygotes tend to have neutrophils with rounded nuclei that do have some functional problems. Homozygous individuals inconsistently have skeletal anomalies such as post-axial polydactyly, short metacarpals, short upper limbs, short stature, or hyperkyphosis.[citation needed]

- Hoffmann, Katrin; Dreger, Christine K.; Olins, Ada L.; Olins, Donald E.; Shultz, Leonard D.; Lucke, Barbara; Karl, Hartmut; Kaps, Reinhard; Müller, Dietmar; Vayá, Amparo; Aznar, Justo; Ware, Russell E.; Cruz, Norberto Sotelo; Lindner, Tom H.; Herrmann, Harald; Reis, André; Sperling, Karl (2002). “Mutations in the gene encoding the lamin B receptor produce an altered nuclear morphology in granulocytes (Pelger–Huët anomaly)”. Nature Genetics. 31 (4): 410–4. doi:10.1038/ng925. PMID 12118250. S2CID 6020153.

- Vale, A. M.; Tomaz, L. R.; Sousa, R. S.; Soto-Blanco, B. (2011). “Pelger-Huët anomaly in two related mixed-breed dogs”. Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation. 23 (4): 863–5. doi:10.1177/1040638711407891. PMID 21908340.

Identifying Pelger–Huët anomaly is important to differentiate from bandemia with a left-shifted peripheral blood smear and neutrophilic band forms and from an increase in young neutrophilic forms that can be observed in association with infection.[citation needed]

Acquired or pseudo-Pelger–Huët anomaly

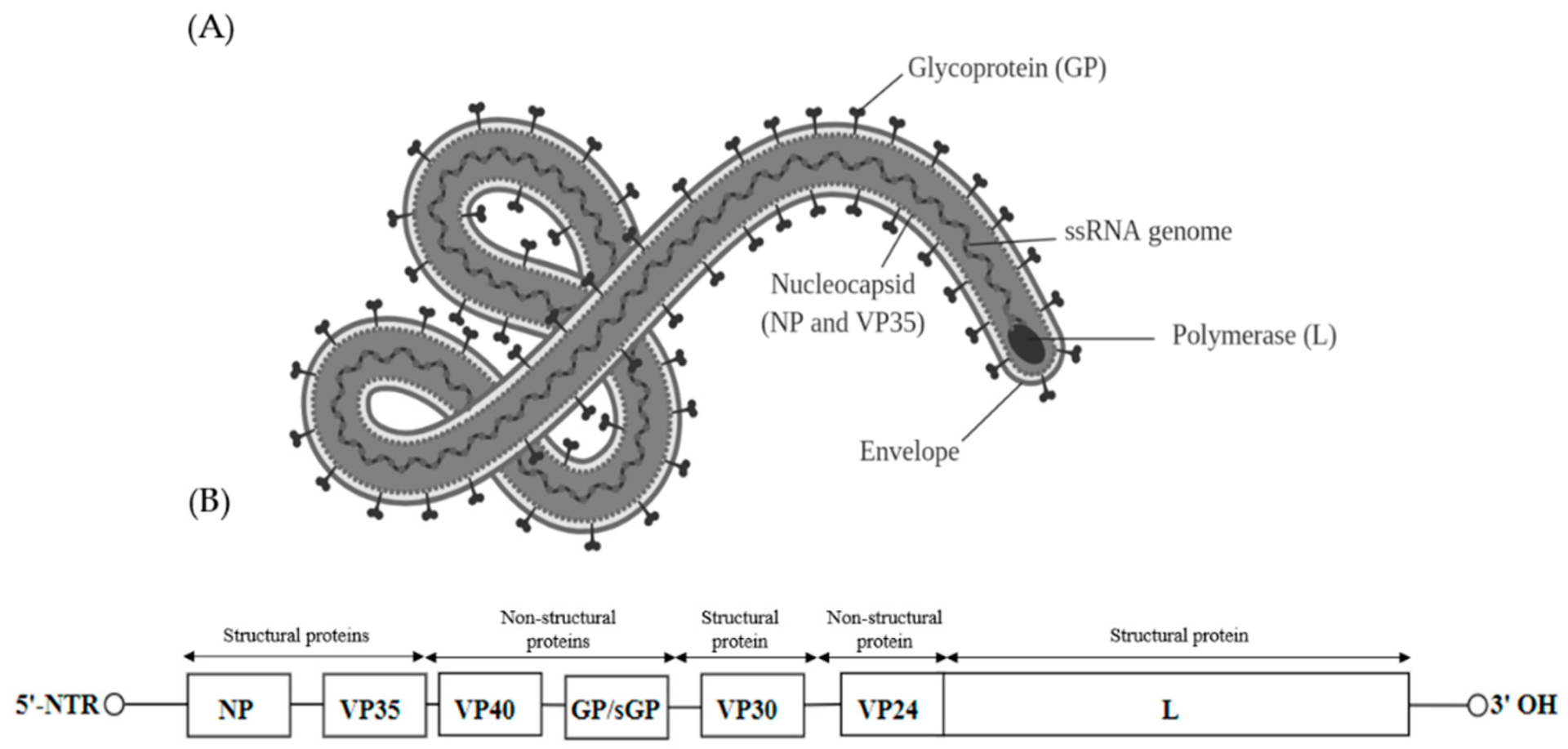

Anomalies resembling Pelger–Huët anomaly that are acquired rather than congenital have been described as pseudo Pelger–Huët anomaly. These can develop in the course of acute myelogenous leukemia or chronic myelogenous leukemia and in myelodysplastic syndrome. It has also been described in Filovirus disease.

- Gear, JS; Cassel, GA; Gear, AJ; Trappler, B; Clausen, L; Meyers, AM; Kew, MC; Bothwell, TH; Sher, R; Miller, GB; Schneider, J; Koornhof, HJ; Gomperts, ED; Isaäcson, M; Gear, JH (1975). “Outbreake of Marburg virus disease in Johannesburg”. British Medical Journal. 4 (5995): 489–93. doi:10.1136/bmj.4.5995.489. PMC 1675587. PMID 811315.

In patients with these conditions, the pseudo–Pelger–Huët cells tend to appear late in the disease and often appear after considerable chemotherapy has been administered. The morphologic changes have also been described in myxedema associated with panhypopituitarism, vitamin B12 and folate deficiency, multiple myeloma, enteroviral infections, malaria, muscular dystrophy, leukemoid reaction secondary to metastases to the bone marrow, and drug sensitivity, sulfa and valproate toxicities are examples. In some of these conditions, especially the drug-induced cases, it is important to differentiate between Pelger–Huët anomaly and pseudo-Pelger–Huët to prevent the need for further unnecessary testing for cancer.[citation needed]

- Singh, Nishith K.; Nagendra, Sanjai (2008). “Reversible Neutrophil Abnormalities Related to Supratherapeutic Valproic Acid Levels”. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 83 (5): 600. doi:10.4065/83.5.600. PMID 18452694.

Peripheral blood smear shows a predominance of neutrophils with bilobed nuclei which are composed of two nuclear masses connected with a thin filament of chromatin. It resembles the pince-nez glasses, so it is often referred to as pince-nez appearance. Usually the congenital form is not associated with thrombocytopenia and leukopenia, so if these features are present more detailed search for myelodysplasia is warranted, as pseudo-Pelger–Huët anomaly can be an early feature of myelodysplasia.

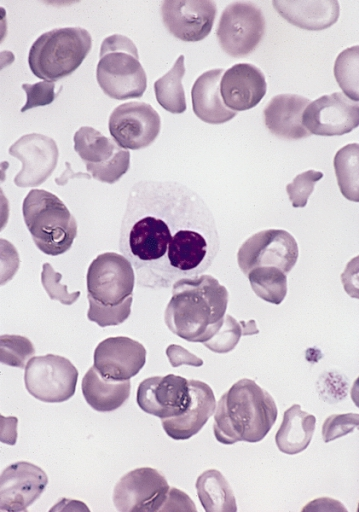

Filoviridae is a family of single-stranded negative-sense RNA viruses in the order Mononegavirales. Two members of the family that are commonly known are Ebola virus and Marburg virus. Both viruses, and some of their lesser known relatives, cause severe disease in humans and nonhuman primates in the form of viral hemorrhagic fevers.

- “Filoviridae”. Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Retrieved July 28, 2018.

- Kuhn, JH; Amarasinghe, GK; Basler, CF; Bavari, S; Bukreyev, A; Chandran, K; Crozier, I; Dolnik, O; Dye, JM; Formenty, PBH; Griffiths, A; Hewson, R; Kobinger, GP; Leroy, EM; Mühlberger, E; Netesov, SV; Palacios, G; Pályi, B; Pawęska, JT; Smither, SJ; Takada, A; Towner, JS; Wahl, V; ICTV Report, Consortium (June 2019). “ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Filoviridae”. The Journal of General Virology. 100 (6): 911–912. doi:10.1099/jgv.0.001252. PMC 7011696. PMID 31021739.

- Kiley MP, Bowen ET, Eddy GA, Isaäcson M, Johnson KM, McCormick JB, Murphy FA, Pattyn SR, Peters D, Prozesky OW, Regnery RL, Simpson DI, Slenczka W, Sureau P, van der Groen G, Webb PA, Wulff H (1982). “Filoviridae: A taxonomic home for Marburg and Ebola viruses?”. Intervirology. 18 (1–2): 24–32. doi:10.1159/000149300. PMID 7118520.

All filoviruses are classified by the US as select agents, by the World Health Organization as Risk Group 4 Pathogens (requiring Biosafety Level 4-equivalent containment), by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases as Category A Priority Pathogens, and by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as Category A Bioterrorism Agents, and are listed as Biological Agents for Export Control by the Australia Group.

- US Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) and US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). “National Select Agent Registry (NSAR)”. Retrieved 2011-10-16.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. “Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories (BMBL) 5th Edition”. Retrieved 2011-10-16.

- US National Institutes of Health (NIH), US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). “Biodefense — NIAID Category A, B, and C Priority Pathogens”. Archived from the original on 2011-10-22. Retrieved 2011-10-16.

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). “Bioterrorism Agents/Diseases”. Archived from the original on July 22, 2014. Retrieved 2011-10-16.

- The Australia Group. “List of Biological Agents for Export Control”. Archived from the original on 2011-08-06. Retrieved 2011-10-16.

The family Filoviridae is a virological taxon that was defined in 1982 and emended in 1991, 1998,[10] 2000, 2005, 2010 and 2011. The family currently includes the six virus genera Cuevavirus, Dianlovirus, Ebolavirus, Marburgvirus, Striavirus, and Thamnovirus and is included in the order Mononegavirales. The members of the family (i.e. the actual physical entities) are called filoviruses or filovirids. The name Filoviridae is derived from the Latin noun filum (alluding to the filamentous morphology of filovirions) and the taxonomic suffix -viridae (which denotes a virus family). According to the rules for taxon naming established by the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV), the name Filoviridae is always to be capitalized, italicized, never abbreviated, and to be preceded by the word “family”. The names of its members (filoviruses or filovirids) are to be written in lower case, are not italicized, and used without articles.

- Kiley MP, Bowen ET, Eddy GA, Isaäcson M, Johnson KM, McCormick JB, Murphy FA, Pattyn SR, Peters D, Prozesky OW, Regnery RL, Simpson DI, Slenczka W, Sureau P, van der Groen G, Webb PA, Wulff H (1982). “Filoviridae: A taxonomic home for Marburg and Ebola viruses?”. Intervirology. 18 (1–2): 24–32. doi:10.1159/000149300. PMID 7118520.

- McCormick, J. B. (1991). “Family Filoviridae”. In Francki, R. I. B.; Fauquet, C. M.; Knudson, D. L.; et al. (eds.). Classification and Nomenclature of Viruses-Fifth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Archives of Virology Supplement. Vol. 2. Vienna, Austria: Springer. pp. 247–49. ISBN 0-387-82286-0.

- Jahrling, P. B.; Kiley, M. P.; Klenk, H.-D.; Peters, C. J.; Sanchez, A.; Swanepoel, R. (1995). “Family Filoviridae”. In Murphy, F. A.; Fauquet, C. M.; Bishop, D. H. L.; Ghabrial, S. A.; Jarvis, A. W.; Martelli, G. P.; Mayo, M. A.; Summers, M. D. (eds.). Virus Taxonomy—Sixth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Archives of Virology Supplement. Vol. 10. Vienna, Austria: Springer. pp. 289–92. ISBN 3-211-82594-0.

- Netesov, S.V.; Feldmann, H.; Jahrling, P. B.; Klenk, H. D.; Sanchez, A. (2000). “Family Filoviridae”. In van Regenmortel, M. H. V.; Fauquet, C. M.; Bishop, D. H. L.; Carstens, E. B.; Estes, M. K.; Lemon, S. M.; Maniloff, J.; Mayo, M. A.; McGeoch, D. J.; Pringle, C. R.; Wickner, R. B. (eds.). Virus Taxonomy—Seventh Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. San Diego, USA: Academic Press. pp. 539–48. ISBN 0-12-370200-3.

- Feldmann, H.; Geisbert, T. W.; Jahrling, P. B.; Klenk, H.-D.; Netesov, S. V.; Peters, C. J.; Sanchez, A.; Swanepoel, R.; Volchkov, V. E. (2005). “Family Filoviridae”. In Fauquet, C. M.; Mayo, M. A.; Maniloff, J.; Desselberger, U.; Ball, L. A. (eds.). Virus Taxonomy—Eighth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. San Diego, USA: Elsevier/Academic Press. pp. 645–653. ISBN 0-12-370200-3.

- Kuhn JH, Becker S, Ebihara H, Geisbert TW, Johnson KM, Kawaoka Y, Lipkin WI, Negredo AI, Netesov SV, Nichol ST, Palacios G, Peters CJ, Tenorio A, Volchkov VE, Jahrling PB (2010). “Proposal for a revised taxonomy of the family Filoviridae: Classification, names of taxa and viruses, and virus abbreviations”. Archives of Virology. 155 (12): 2083–2103. doi:10.1007/s00705-010-0814-x. PMC 3074192. PMID 21046175.

- Kuhn, J. H.; Becker, S.; Ebihara, H.; Geisbert, T. W.; Jahrling, P. B.; Kawaoka, Y.; Netesov, S. V.; Nichol, S. T.; Peters, C. J.; Volchkov, V. E.; Ksiazek, T. G. (2011). “Family Filoviridae”. In King, Andrew M. Q.; Adams, Michael J.; Carstens, Eric B.; et al. (eds.). Virus Taxonomy—Ninth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. London, UK: Elsevier/Academic Press. pp. 665–671. ISBN 978-0-12-384684-6.

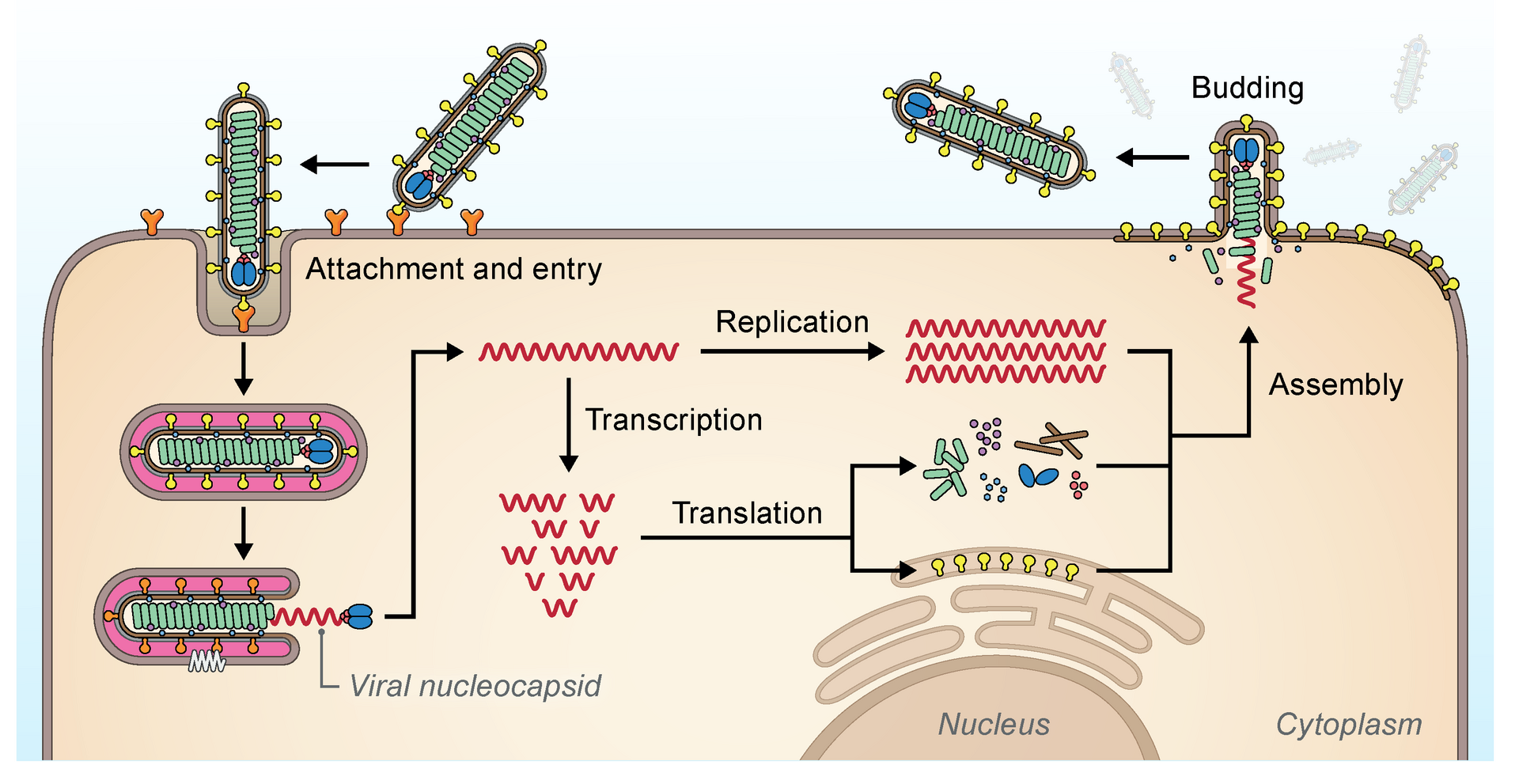

The filovirus life cycle begins with virion attachment to specific cell-surface receptors, followed by fusion of the virion envelope with cellular membranes and the concomitant release of the virus nucleocapsid into the cytosol. The viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp, or RNA replicase) partially uncoats the nucleocapsid and transcribes the genes into positive-stranded mRNAs, which are then translated into structural and nonstructural proteins. Filovirus RdRps bind to a single promoter located at the 3′ end of the genome. Transcription either terminates after a gene or continues to the next gene downstream. This means that genes close to the 3′ end of the genome are transcribed in the greatest abundance, whereas those toward the 5′ end are least likely to be transcribed. The gene order is therefore a simple but effective form of transcriptional regulation. The most abundant protein produced is the nucleoprotein, whose concentration in the cell determines when the RdRp switches from gene transcription to genome replication. Replication results in full-length, positive-stranded antigenomes that are in turn transcribed into negative-stranded virus progeny genome copies. Newly synthesized structural proteins and genomes self-assemble and accumulate near the inside of the cell membrane. Virions bud off from the cell, gaining their envelopes from the cellular membrane they bud from. The mature progeny particles then infect other cells to repeat the cycle.

- Feldmann, H.; Geisbert, T. W.; Jahrling, P. B.; Klenk, H.-D.; Netesov, S. V.; Peters, C. J.; Sanchez, A.; Swanepoel, R.; Volchkov, V. E. (2005). “Family Filoviridae”. In Fauquet, C. M.; Mayo, M. A.; Maniloff, J.; Desselberger, U.; Ball, L. A. (eds.). Virus Taxonomy—Eighth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. San Diego, USA: Elsevier/Academic Press. pp. 645–653. ISBN 0-12-370200-3.

A virus that fulfills the criteria for being a member of the order Mononegavirales is a member of the family Filoviridae if:

- it causes viral hemorrhagic fever in certain primates

- it infects primates, pigs or bats in nature

- it needs to be adapted through serial passage to cause disease in rodents

- it exclusively replicates in the cytoplasm of a host cell

- it has a genome ≈19 kbp in length

- it has an RNA genome that constitutes ≈1.1% of the virion mass

- its genome has a molecular weight of ≈4.2×106

- its genome contains one or more gene overlaps

- its genome contains seven genes in the order 3′-UTR-NP-VP35-VP40-GP-VP30-VP24-L-5′-UTR

- its VP24 gene is not homologous to genes of other mononegaviruses

- its genome contains transcription initiation and termination signals not found in genomes of other mononegaviruses

- it forms nucleocapsids with a buoyant density in CsCl of ≈1.32 g/cm3

- it forms nucleocapsids with a central axial channel (≈10–15 nm in width) surrounded by a dark layer (≈20 nm in width) and an outer helical layer (≈50 nm in width) with a cross striation (periodicity of ≈5 nm)

- it expresses a class I fusion glycoprotein that is highly N- and O-glycosylated and acylated at its cytoplasmic tail

- it expresses a primary matrix protein that is not glycosylated

- it forms virions that bud from the plasma membrane

- it forms virions that are predominantly filamentous (U- and 6-shaped) and that are ≈80 nm in width, and several hundred nm and up to 14 μm in length

- it forms virions that have surface projections ≈7 nm in length spaced ≈10 nm apart from each other

- it forms virions with a molecular mass of ≈3.82×108; an S20W of at least 1.40; and a buoyant density in potassium tartrate of ≈1.14 g/cm3

- it forms virions that are poorly neutralized in vivo

- Kuhn JH, Becker S, Ebihara H, Geisbert TW, Johnson KM, Kawaoka Y, Lipkin WI, Negredo AI, Netesov SV, Nichol ST, Palacios G, Peters CJ, Tenorio A, Volchkov VE, Jahrling PB (2010). “Proposal for a revised taxonomy of the family Filoviridae: Classification, names of taxa and viruses, and virus abbreviations”. Archives of Virology. 155 (12): 2083–2103. doi:10.1007/s00705-010-0814-x. PMC 3074192. PMID 21046175.

- Kuhn, J. H.; Becker, S.; Ebihara, H.; Geisbert, T. W.; Jahrling, P. B.; Kawaoka, Y.; Netesov, S. V.; Nichol, S. T.; Peters, C. J.; Volchkov, V. E.; Ksiazek, T. G. (2011). “Family Filoviridae”. In King, Andrew M. Q.; Adams, Michael J.; Carstens, Eric B.; et al. (eds.). Virus Taxonomy—Ninth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. London, UK: Elsevier/Academic Press. pp. 665–671. ISBN 978-0-12-384684-6.

| Genus name | Species name | Virus name (abbreviation) |

|---|---|---|

| Cuevavirus | Lloviu cuevavirus | Lloviu virus (LLOV) |

| Dianlovirus | Mengla dianlovirus | Měnglà virus (MLAV) |

| Ebolavirus | Bombali ebolavirus | Bombali virus (BOMV) |

| Bundibugyo ebolavirus | Bundibugyo virus (BDBV; previously BEBOV) | |

| Reston ebolavirus | Reston virus (RESTV; previously REBOV) | |

| Sudan ebolavirus | Sudan virus (SUDV; previously SEBOV) | |

| Taï Forest ebolavirus | Taï Forest virus (TAFV; previously CIEBOV) | |

| Zaire ebolavirus | Ebola virus (EBOV; previously ZEBOV) | |

| Marburgvirus | Marburg marburgvirus | Marburg virus (MARV) |

| Ravn virus (RAVV) | ||

| Striavirus | Xilang striavirus | Xīlǎng virus (XILV) |

| Thamnovirus | Huangjiao thamnovirus | Huángjiāo virus (HUJV) |

Filoviruses have a history that dates back several tens of million of years. Endogenous viral elements (EVEs) that appear to be derived from filovirus-like viruses have been identified in the genomes of bats, rodents, shrews, tenrecs, tarsiers, and marsupials. Although most filovirus-like EVEs appear to be pseudogenes, evolutionary analyses suggest that orthologs isolated from several species of the bat genus Myotis have been maintained by selection.

- Taylor DJ, Leach RW, Bruenn J (2010). “Filoviruses are ancient and integrated into mammalian genomes”. BMC Evolutionary Biology. 10 (1): 193. Bibcode:2010BMCEE..10..193T. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-10-193. PMC 2906475. PMID 20569424.

- Belyi VA, Levine AJ, Skalka AM (2010). Buchmeier (ed.). “Unexpected Inheritance: Multiple Integrations of Ancient Bornavirus and Ebolavirus/Marburgvirus Sequences in Vertebrate Genomes”. PLOS Pathogens. 6 (7): e1001030. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1001030. PMC 2912400. PMID 20686665.

- Katzourakis A, Gifford RJ (2010). “Endogenous Viral Elements in Animal Genomes”. PLOS Genetics. 6 (11): e1001191. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1001191. PMC 2987831. PMID 21124940.

- Taylor DJ, Dittmar K, Ballinger MJ, Bruenn JA (2011). “Evolutionary maintenance of filovirus-like genes in bat genomes”. BMC Evolutionary Biology. 11 (336): 336. Bibcode:2011BMCEE..11..336T. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-11-336. PMC 3229293. PMID 22093762.

There are presently very limited vaccines for known filovirus. An effective vaccine against EBOV, developed in Canada, was approved for use in 2019 in the US and Europe. Similarly, efforts to develop a vaccine against Marburg virus are under way.

- Peters CJ, LeDuc JW (February 1999). “An Introduction to Ebola: The Virus and the Disease”. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 179 (Supplement 1): ix–xvi. doi:10.1086/514322. JSTOR 30117592. PMID 9988154.

- Plummer, Francis A.; Jones, Steven M. (2017-10-30). “The story of Canada’s Ebola vaccine”. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal. 189 (43): E1326–E1327. doi:10.1503/cmaj.170704. ISSN 0820-3946. PMC 5662448. PMID 29084758.

- Research, Center for Biologics Evaluation and (2020-01-27). “ERVEBO”. FDA.

- CZARSKA-THORLEY, Dagmara (2019-10-16). “Ervebo”. European Medicines Agency. Retrieved 2020-05-03.

- Keshwara, Rohan; Hagen, Katie R.; Abreu-Mota, Tiago; Papaneri, Amy B.; Liu, David; Wirblich, Christoph; Johnson, Reed F.; Schnell, Matthias J. (2019-03-05). “A Recombinant Rabies Virus Expressing the Marburg Virus Glycoprotein Is Dependent upon Antibody-Mediated Cellular Cytotoxicity for Protection against Marburg Virus Disease in a Murine Model”. Journal of Virology. 93 (6). doi:10.1128/JVI.01865-18. ISSN 0022-538X. PMC 6401435. PMID 30567978.

There has been a pressing concern that a very slight genetic mutation to a filovirus such as EBOV could result in a change in transmission system from direct body fluid transmission to airborne transmission, as was seen in Reston virus (another member of genus Ebolavirus) between infected macaques. A similar change in the current circulating strains of EBOV could greatly increase the infection and disease rates caused by EBOV. However, there is no record of any Ebola strain ever having made this transition in humans. The Department of Homeland Security’s National Biodefense Analysis and Countermeasures Center considers the risk of a mutated Ebola virus strain with aerosol transmission capability emerging in the future as a serious threat to national security and has collaborated with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to design methods to detect EBOV aerosols.

- Kelland, Kate (19 September 2014). “Scientists see risk of mutant airborne Ebola as remote”. Reuters. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- “Feature Article: New Tech Makes Detecting Airborne Ebola Virus Possible”. Department of Homeland Security. 20 April 2021. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

References

- “OMIM Entry – # 169400 – PELGER-HUET ANOMALY; PHA”. omim.org. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- Hoffmann, Katrin; Dreger, Christine K.; Olins, Ada L.; Olins, Donald E.; Shultz, Leonard D.; Lucke, Barbara; Karl, Hartmut; Kaps, Reinhard; Müller, Dietmar; Vayá, Amparo; Aznar, Justo; Ware, Russell E.; Cruz, Norberto Sotelo; Lindner, Tom H.; Herrmann, Harald; Reis, André; Sperling, Karl (2002). “Mutations in the gene encoding the lamin B receptor produce an altered nuclear morphology in granulocytes (Pelger–Huët anomaly)”. Nature Genetics. 31 (4): 410–4. doi:10.1038/ng925. PMID 12118250. S2CID 6020153.

- “Pelger-Huet anomaly”. Disease Infosearch. Retrieved 2020-04-27. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License

- Cunningham, John M.; Patnaik, Mrinal M.; Hammerschmidt, Dale E.; Vercellotti, Gregory M. (2009). “Historical perspective and clinical implications of the Pelger-Huet cell”. American Journal of Hematology. 84 (2): 116–9. doi:10.1002/ajh.21320. PMID 19021122.

- Vale, A. M.; Tomaz, L. R.; Sousa, R. S.; Soto-Blanco, B. (2011). “Pelger-Huët anomaly in two related mixed-breed dogs”. Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation. 23 (4): 863–5. doi:10.1177/1040638711407891. PMID 21908340.

- Gear, JS; Cassel, GA; Gear, AJ; Trappler, B; Clausen, L; Meyers, AM; Kew, MC; Bothwell, TH; Sher, R; Miller, GB; Schneider, J; Koornhof, HJ; Gomperts, ED; Isaäcson, M; Gear, JH (1975). “Outbreake of Marburg virus disease in Johannesburg”. British Medical Journal. 4 (5995): 489–93. doi:10.1136/bmj.4.5995.489. PMC 1675587. PMID 811315.

- Singh, Nishith K.; Nagendra, Sanjai (2008). “Reversible Neutrophil Abnormalities Related to Supratherapeutic Valproic Acid Levels”. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 83 (5): 600. doi:10.4065/83.5.600. PMID 18452694.

- Pelger-Huet Anomaly at eMedicine

- Paradisi M, McClintock D, Boguslavsky RL, Pedicelli C, Worman HJ, Djabali K (2005). “Dermal fibroblasts in Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome with the lamin A G608G mutation have dysmorphic nuclei and are hypersensitive to heat stress”. BMC Cell Biol. 6: 27. doi:10.1186/1471-2121-6-27. PMC 1183198. PMID 15982412.

- Nagano A, Arahata K (2000). “Nuclear envelope proteins and associated diseases”. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 13 (5): 533–9. doi:10.1097/00019052-200010000-00005. PMID 11073359. S2CID 12550140.

- Vergnes L, Peterfy M, Bergo MO, Young SG, Reue K (2004). “Lamin B1 is required for mouse development and nuclear integrity”. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101 (28): 10428–33. Bibcode:2004PNAS..10110428V. doi:10.1073/pnas.0401424101. PMC 478588. PMID 15232008.

- Hegele RA, Cao H, Liu DM, Costain GA, Charlton-Menys V, Rodger NW, Durrington PN (2006). “Sequencing of the reannotated LMNB2 gene reveals novel mutations in patients with acquired partial lipodystrophy”. Am J Hum Genet. 79 (2): 383–389. doi:10.1086/505885. PMC 1559499. PMID 16826530.

- Padiath QS, Saigoh K, Schiffmann R, Asahara H, Yamada T, Koeppen A, Hogan K, Ptácek LJ, Fu YH (2006). “Lamin B1 duplications cause autosomal dominant leukodystrophy”. Nat Genet. 38 (10): 1114–1123. doi:10.1038/ng1872. PMID 16951681. S2CID 25336497.

- Hoffmann, Katrin; Dreger, Christine K.; Olins, Ada L.; Olins, Donald E.; Shultz, Leonard D.; Lucke, Barbara; Karl, Hartmut; Kaps, Reinhard; Müller, Dietmar; Vayá, Amparo; Aznar, Justo (2002-07-15). “Mutations in the gene encoding the lamin B receptor produce an altered nuclear morphology in granulocytes (Pelger–Huët anomaly)”. Nature Genetics. 31 (4): 410–414. doi:10.1038/ng925. ISSN 1061-4036. PMID 12118250. S2CID 6020153.

- Waterham, Hans R.; Koster, Janet; Mooyer, Petra; Noort, Gerard van; Kelley, Richard I.; Wilcox, William R.; Ronald Wanders, J.A.; Raoul Hennekam, C.M.; Jan Oosterwijk, C. (April 2003). “Autosomal Recessive HEM/Greenberg Skeletal Dysplasia Is Caused by 3β-Hydroxysterol Δ14-Reductase Deficiency Due to Mutations in the Lamin B Receptor Gene”. The American Journal of Human Genetics. 72 (4): 1013–1017. doi:10.1086/373938. ISSN 0002-9297. PMC 1180330. PMID 12618959.

- Greenberg, Cheryl R.; Rimoin, David L.; Gruber, Helen E.; DeSa, D. J. B.; Reed, M.; Lachman, Ralph S.; Optiz, John M.; Reynolds, James F. (March 1988). “A new autosomal recessive lethal chondrodystrophy with congenital hydrops”. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 29 (3): 623–632. doi:10.1002/ajmg.1320290321. ISSN 0148-7299. PMID 3377005.

- Shultz, L. D. (2003-01-01). “Mutations at the mouse ichthyosis locus are within the lamin B receptor gene: a single gene model for human Pelger-Huet anomaly”. Human Molecular Genetics. 12 (1): 61–69. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddg003. ISSN 1460-2083. PMID 12490533.

- Young, Alexander Neil; Perlas, Emerald; Ruiz-Blanes, Nerea; Hierholzer, Andreas; Pomella, Nicola; Martin-Martin, Belen; Liverziani, Alessandra; Jachowicz, Joanna W.; Giannakouros, Thomas; Cerase, Andrea (2021-04-12). “Deletion of LBR N-terminal domains recapitulates Pelger-Huet anomaly phenotypes in mouse without disrupting X chromosome inactivation”. Communications Biology. 4 (1): 478. doi:10.1038/s42003-021-01944-2. ISSN 2399-3642. PMC 8041748. PMID 33846535.

- Mans BJ, Anantharaman V, Aravind L, Koonin EV (2004). “Comparative genomics, evolution and origins of the nuclear envelope and nuclear pore complex”. Cell Cycle. 3 (12): 1612–37. doi:10.4161/cc.3.12.1316. PMID 15611647.

- Houben F, Ramaekers FC, Snoeckx LH, Broers JL (May 2007). “Role of nuclear lamina-cytoskeleton interactions in the maintenance of cellular strength”. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1773 (5): 675–86. doi:10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.09.018. PMID 17050008.

- Hegele RA, Cao H, Liu DM, Costain GA, Charlton-Menys V, Rodger NW, Durrington PN (2006). “Sequencing of the reannotated LMNB2 gene reveals novel mutations in patients with acquired partial lipodystrophy”. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 79 (2): 383–9. doi:10.1086/505885. PMC 1559499. PMID 16826530.

- Novelli G, Muchir A, Sangiuolo F, Helbling-Leclerc A, D’Apice MR, Massart C, Capon F, Sbraccia P, Federici M, Lauro R, Tudisco C, Pallotta R, Scarano G, Dallapiccola B, Merlini L, Bonne G (2002). “Mandibuloacral dysplasia is caused by a mutation in LMNA-encoding lamin A/C”. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 71 (2): 426–31. doi:10.1086/341908. PMC 379176. PMID 12075506.

- Zirn B, Kress W, Grimm T, Berthold LD, et al. (2008). “Association of homozygous LMNA mutation R471C with new phenotype: mandibuloacral dysplasia, progeria, and rigid spine muscular dystrophy”. Am J Med Genet A. 146A (8): 1049–1054. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.32259. PMID 18348272. S2CID 205309256.

- Al-Haggar M, Madej-Pilarczyk A, Kozlowski L, Bujnicki JM, Yahia S, Abdel-Hadi D, Shams A, Ahmad N, Hamed S, Puzianowska-Kuznicka M (2012). “A novel homozygous p.Arg527Leu LMNA mutation in two unrelated Egyptian families causes overlapping mandibuloacral dysplasia and progeria syndrome”. Eur J Hum Genet. 20 (11): 1134–40. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2012.77. PMC 3476705. PMID 22549407.

- Eriksson M, Brown WT, Gordon LB, Glynn MW, Singer J, Scott L, Erdos MR, Robbins CM, Moses TY, Berglund P, Dutra A, Pak E, Durkin S, Csoka AB, Boehnke M, Glover TW, Collins FS (2003). “Recurrent de novo point mutations in lamin A cause Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome”. Nature. 423 (6937): 293–8. Bibcode:2003Natur.423..293E. doi:10.1038/nature01629. hdl:2027.42/62684. PMC 10540076. PMID 12714972. S2CID 4420150.

- Navarro CL, De Sandre-Giovannoli A, Bernard R, Boccaccio I, Boyer A, Genevieve D, Hadj-Rabia S, Gaudy-Marqueste C, Smitt HS, Vabres P, Faivre L, Verloes A, Van Essen T, Flori E, Hennekam R, Beemer FA, Laurent N, Le Merrer M, Cau P, Levy N (2004). “Lamin A and ZMPSTE24 (FACE-1) defects cause nuclear disorganization and identity restrictive dermopathy as a lethal neonatal laminopathy”. Hum. Mol. Genet. 13 (20): 2493–2503. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddh265. PMID 15317753.

- Padiath QS, Saigoh K, Schiffmann R, Asahara H, Yamada T, Koeppen A, Hogan K, Ptacek LJ, Fu YH (2006). “Lamin B1 duplications cause autosomal dominant leukodystrophy”. Nature Genetics. 38 (10): 1114–1123. doi:10.1038/ng1872. PMID 16951681. S2CID 25336497.

- Lassoued K, Guilly MN, Danon F, Andre C, Dhumeaux D, Clauvel JP, Brouet JC, Seligmann M, Courvalin JC (1988). “Antinuclear autoantibodies specific for lamins. Characterization and clinical significance”. Ann Intern Med. 108 (6): 829–3. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-108-6-829. PMID 3285745.

- Redwood AB, Perkins SM, Vanderwaal RP, Feng Z, Biehl KJ, Gonzalez-Suarez I, Morgado-Palacin L, Shi W, Sage J, Roti-Roti JL, Stewart CL, Zhang J, Gonzalo S (2011). “A dual role for A-type lamins in DNA double-strand break repair”. Cell Cycle. 10 (15): 2549–60. doi:10.4161/cc.10.15.16531. PMC 3180193. PMID 21701264.

- Liu B, Wang J, Chan KM, Tjia WM, Deng W, Guan X, Huang JD, Li KM, Chau PY, Chen DJ, Pei D, Pendas AM, Cadiñanos J, López-Otín C, Tse HF, Hutchison C, Chen J, Cao Y, Cheah KS, Tryggvason K, Zhou Z (2005). “Genomic instability in laminopathy-based premature aging”. Nat. Med. 11 (7): 780–5. doi:10.1038/nm1266. PMID 15980864. S2CID 11798376.

- Chen L, Lee L, Kudlow BA, Dos Santos HG, Sletvold O, Shafeghati Y, Botha EG, Garg E, Hanson NB, Martin GM, Mian IS, Kennedy BK, Oshima J (2003). “LMNA mutations in atypical Werner’s syndrome”. Lancet. 362 (9382): 440–5. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14069-X. PMID 12927431. S2CID 21980784.

- Hellemans J, Preobrazhenska O, Willaert A, Debeer P, Verdonk PCM, Costa T, Janssens K, Menten B, Van Roy N, Vermeulen SJT, Savarirayan R, Van Hul W, et al. (2004). “Loss-of-function mutations in LEMD3 result in osteopoikilosis, Buschke–Ollendorff syndrome and melorheostosis”. Nature Genetics. 36 (11): 1213–8. doi:10.1038/ng1453. PMID 15489854.

- Fatkin D, MacRae C, Sasaki T, Wolff MR, Porcu M, Frenneaux M, Atherton J, Vidaillet HJ, Spudich S, De Girolami U, Seidman JG, Seidman CE (1999). “Missense mutations in the rod domain of the lamin A/C gene as causes of dilated cardiomyopathy and conduction-system disease” (PDF). N. Engl. J. Med. 341 (23): 1715–24. doi:10.1056/NEJM199912023412302. PMID 10580070. S2CID 22942654.

- Charniot JC, Pascal C, Bouchier C, Sebillon P, Salama J, Duboscq-Bidot L, Peuchmaurd M, Desnos M, Artigou JY, Komajda M (2003). “Functional consequences of an LMNA mutation associated with a new cardiac and non-cardiac phenotype”. Hum. Mutat. 21 (5): 473–81. doi:10.1002/humu.10170. PMID 12673789. S2CID 32614095.

- De Sandre-Giovannoli A, Chaouch M, Kozlov S, Vallat JM, Tazir M, Kassouri N, Szepetowski P, Hammadouche T, Vandenberghe A, Stewart CL, Grid D, Levy N (2002). “Homozygous defects in LMNA, encoding lamin A/C nuclear-envelope proteins, cause autosomal recessive axonal neuropathy in human (Charcot–Marie–Tooth disorder type 2) and mouse”. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 70 (3): 726–36. doi:10.1086/339274. PMC 384949. PMID 11799477.

- Manilal S, Nguyen TM, Sewry CA, Morris GE (1996). “The Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophy protein, emerin, is a nuclear membrane protein”. Hum. Mol. Genet. 5 (6): 801–8. doi:10.1093/hmg/5.6.801. PMID 8776595.

- Clements L, Manilal S, Love DR, Morris GE (2000). “Direct interaction between emerin and lamin A”. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 267 (3): 709–14. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1999.2023. PMID 10673356.

- Bonne G, Di Barletta MR, Varnous S, Becane HM, Hammouda EH, Merlini L, Muntoni F, Greenberg CR, Gary F, Urtizberea JA, Duboc D, Fardeau M, Toniolo D, Schwartz K (1999). “Mutations in the gene encoding lamin A/C cause autosomal dominant Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophy”. Nature Genetics. 21 (3): 285–8. doi:10.1038/6799. PMID 10080180. S2CID 7327176.

- Raffaele di Barletta M, Ricci E, Galluzzi G, Tonali P, Mora M, Morandi L, Romorini A, Voit T, Orstavik KH, Merlini L, Trevisan C, Biancalana V, Hausmanowa-Petrusewicz I, Bione S, Ricotti R, Schwartz K, Bonne G, Toniolo D (2000). “Different mutations in the LMNA gene cause autosomal dominant and autosomal recessive Emery–Dreifuss muscular dystrophy”. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 66 (4): 1407–12. doi:10.1086/302869. PMC 1288205. PMID 10739764.

- Cao H, Hegele RA (2002). “Nuclear lamin A/C R482Q mutation in Canadian kindreds with Dunnigan-type familial partial lipodystrophy”. Hum. Mol. Genet. 9 (1): 109–12. doi:10.1093/hmg/9.1.109. PMID 10587585.

- Waterham HR, Koster J, Mooyer P, van Noort G, Kelley RI, Wilcox WR, Wanders RJ, Hennekam RC, Oosterwijk JC (2003). “Autosomal recessive HEM/Greenberg skeletal dysplasia is caused by 3-beta-hydroxysterol delta(14)-reductase deficiency due to mutations in the lamin B receptor gene”. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 72 (4): 1013–17. doi:10.1086/373938. PMC 1180330. PMID 12618959.

- Muchir A, Bonne G, van der Kooi AJ, van Meegen M, Baas F, Bolhuis PA, de Visser M, Schwartz K (2000). “Identification of mutations in the gene encoding lamins A/C in autosomal dominant limb girdle muscular dystrophy with atrioventricular conduction disturbances (LGMD1B)”. Hum. Mol. Genet. 9 (9): 1453–9. doi:10.1093/hmg/9.9.1453. PMID 10814726.

- Caux F, Dubosclard E, Lascols O, Buendia B, Chazouilleres O, Cohen A, Courvalin JC, Laroche L, Capeau J, Vigouroux C, Christin-Maitre S (2003). “A new clinical condition linked to a novel mutation in lamins A and C with generalized lipoatrophy, insulin-resistant diabetes, disseminated leukomelanodermic papules, liver steatosis, and cardiomyopathy”. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 88 (3): 1006–13. doi:10.1210/jc.2002-021506. PMID 12629077.

- Agarwal AK, Fryns JP, Auchus RJ, Garg A (2003). “Zinc metalloproteinase, ZMPSTE24, is mutated in mandibuloacral dysplasia”. Hum. Mol. Genet. 12 (16): 1995–2001. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddg213. PMID 12913070.

- Hoffmann K, Dreger CK, Olins AL, Olins DE, Shultz LD, Lucke B, Karl H, Kaps R, Muller D, Vaya A, Aznar J, Ware RE, Cruz NS, Lindner TH, Herrmann H, Reis A, Sperling K (2002). “Mutations in the gene encoding the lamin B receptor produce an altered nuclear morphology in granulocytes (Pelger-Huet anomaly)”. Nature Genetics. 31 (4): 410–4. doi:10.1038/ng925. PMID 12118250. S2CID 6020153.

- Captur, Gabriella; Arbustini, Eloisa; Bonne, Gisèle; Syrris, Petros; Mills, Kevin; Wahbi, Karim; Mohiddin, Saidi A.; McKenna, William J.; Pettit, Stephen (2017-11-25). “Lamin and the heart” (PDF). Heart. 104 (6): 468–479. doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2017-312338. ISSN 1468-201X. PMID 29175975. S2CID 3563474.

- Rusinal AE, Sinensky MS (2006). “Farnesylated lamins, progeroid syndromes and farnesyl transferase inhibitors”. J. Cell Sci. 119 (Pt 16): 3265–72. doi:10.1242/jcs.03156. PMID 16899817.

- Meta M, Yang SH, Bergo MO, Fong LG, Young SG (2006). “Protein farnesyltransferase inhibitors and progeria”. Trends Mol. Med. 12 (10): 480–7. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2006.08.006. PMID 16942

- “Filoviridae”. Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Retrieved July 28, 2018.

- Kuhn, JH; Amarasinghe, GK; Basler, CF; Bavari, S; Bukreyev, A; Chandran, K; Crozier, I; Dolnik, O; Dye, JM; Formenty, PBH; Griffiths, A; Hewson, R; Kobinger, GP; Leroy, EM; Mühlberger, E; Netesov, SV; Palacios, G; Pályi, B; Pawęska, JT; Smither, SJ; Takada, A; Towner, JS; Wahl, V; ICTV Report, Consortium (June 2019). “ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Filoviridae”. The Journal of General Virology. 100 (6): 911–912. doi:10.1099/jgv.0.001252. PMC 7011696. PMID 31021739.

- Kiley MP, Bowen ET, Eddy GA, Isaäcson M, Johnson KM, McCormick JB, Murphy FA, Pattyn SR, Peters D, Prozesky OW, Regnery RL, Simpson DI, Slenczka W, Sureau P, van der Groen G, Webb PA, Wulff H (1982). “Filoviridae: A taxonomic home for Marburg and Ebola viruses?”. Intervirology. 18 (1–2): 24–32. doi:10.1159/000149300. PMID 7118520.

- US Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) and US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). “National Select Agent Registry (NSAR)”. Retrieved 2011-10-16.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. “Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories (BMBL) 5th Edition”. Retrieved 2011-10-16.

- US National Institutes of Health (NIH), US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). “Biodefense — NIAID Category A, B, and C Priority Pathogens”. Archived from the original on 2011-10-22. Retrieved 2011-10-16.

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). “Bioterrorism Agents/Diseases”. Archived from the original on July 22, 2014. Retrieved 2011-10-16.

- The Australia Group. “List of Biological Agents for Export Control”. Archived from the original on 2011-08-06. Retrieved 2011-10-16.

- McCormick, J. B. (1991). “Family Filoviridae”. In Francki, R. I. B.; Fauquet, C. M.; Knudson, D. L.; et al. (eds.). Classification and Nomenclature of Viruses-Fifth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Archives of Virology Supplement. Vol. 2. Vienna, Austria: Springer. pp. 247–49. ISBN 0-387-82286-0.

- Jahrling, P. B.; Kiley, M. P.; Klenk, H.-D.; Peters, C. J.; Sanchez, A.; Swanepoel, R. (1995). “Family Filoviridae”. In Murphy, F. A.; Fauquet, C. M.; Bishop, D. H. L.; Ghabrial, S. A.; Jarvis, A. W.; Martelli, G. P.; Mayo, M. A.; Summers, M. D. (eds.). Virus Taxonomy—Sixth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Archives of Virology Supplement. Vol. 10. Vienna, Austria: Springer. pp. 289–92. ISBN 3-211-82594-0.

- Netesov, S.V.; Feldmann, H.; Jahrling, P. B.; Klenk, H. D.; Sanchez, A. (2000). “Family Filoviridae”. In van Regenmortel, M. H. V.; Fauquet, C. M.; Bishop, D. H. L.; Carstens, E. B.; Estes, M. K.; Lemon, S. M.; Maniloff, J.; Mayo, M. A.; McGeoch, D. J.; Pringle, C. R.; Wickner, R. B. (eds.). Virus Taxonomy—Seventh Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. San Diego, USA: Academic Press. pp. 539–48. ISBN 0-12-370200-3.

- Feldmann, H.; Geisbert, T. W.; Jahrling, P. B.; Klenk, H.-D.; Netesov, S. V.; Peters, C. J.; Sanchez, A.; Swanepoel, R.; Volchkov, V. E. (2005). “Family Filoviridae”. In Fauquet, C. M.; Mayo, M. A.; Maniloff, J.; Desselberger, U.; Ball, L. A. (eds.). Virus Taxonomy—Eighth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. San Diego, USA: Elsevier/Academic Press. pp. 645–653. ISBN 0-12-370200-3.

- Kuhn JH, Becker S, Ebihara H, Geisbert TW, Johnson KM, Kawaoka Y, Lipkin WI, Negredo AI, Netesov SV, Nichol ST, Palacios G, Peters CJ, Tenorio A, Volchkov VE, Jahrling PB (2010). “Proposal for a revised taxonomy of the family Filoviridae: Classification, names of taxa and viruses, and virus abbreviations”. Archives of Virology. 155 (12): 2083–2103. doi:10.1007/s00705-010-0814-x. PMC 3074192. PMID 21046175.

- Kuhn, J. H.; Becker, S.; Ebihara, H.; Geisbert, T. W.; Jahrling, P. B.; Kawaoka, Y.; Netesov, S. V.; Nichol, S. T.; Peters, C. J.; Volchkov, V. E.; Ksiazek, T. G. (2011). “Family Filoviridae”. In King, Andrew M. Q.; Adams, Michael J.; Carstens, Eric B.; et al. (eds.). Virus Taxonomy—Ninth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. London, UK: Elsevier/Academic Press. pp. 665–671. ISBN 978-0-12-384684-6.

- Carroll SA, Towner JS, Sealy TK, McMullan LK, Khristova ML, Burt FJ, Swanepoel R, Rollin PE, Nichol ST (March 2013). “Molecular evolution of viruses of the family Filoviridae based on 97 whole-genome sequences”. J. Virol. 87 (5): 2608–16. doi:10.1128/JVI.03118-12. PMC 3571414. PMID 23255795.

- Li YH, Chen SP (2014). “Evolutionary history of Ebola virus” (PDF). Epidemiol. Infect. 142 (6): 1138–1145. doi:10.1017/S0950268813002215. PMC 9151191. PMID 24040779. S2CID 9873900.

- Taylor, D. J.; Ballinger, M. J.; Zhan, J. J.; Hanzly, L. E.; Bruenn, J. A. (2014). “Evidence that ebolaviruses and cuevaviruses have been diverging from marburgviruses since the Miocene”. PeerJ. 2: e556. doi:10.7717/peerj.556. PMC 4157239. PMID 25237605.

- Melanie M. Hierweger, Michel C. Koch, Melanie Rupp, Piet Maes, Nicholas Di Paola, Rémy Bruggmann, Jens H. Kuhn, Heike Schmidt-Posthaus & Torsten Seuberlich (2021-11-22). “Novel Filoviruses, Hantavirus, and Rhabdovirus in Freshwater Fish, Switzerland, 2017”. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 27 (12): 3082–3091. doi:10.3201/eid2712.210491. PMC 8632185. PMID 34808081.

- Biao He, Tingsong Hu, Xiaomin Yan, Fuqiang Zhang, Changchun Tu (2023-08-07). “Detection and characterization of a novel bat filovirus (Dehong virus, DEHV) in fruit bats”. bioRxiv. doi:10.1101/2023.08.07.552227.

- Taylor DJ, Leach RW, Bruenn J (2010). “Filoviruses are ancient and integrated into mammalian genomes”. BMC Evolutionary Biology. 10 (1): 193. Bibcode:2010BMCEE..10..193T. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-10-193. PMC 2906475. PMID 20569424.

- Belyi VA, Levine AJ, Skalka AM (2010). Buchmeier (ed.). “Unexpected Inheritance: Multiple Integrations of Ancient Bornavirus and Ebolavirus/Marburgvirus Sequences in Vertebrate Genomes”. PLOS Pathogens. 6 (7): e1001030. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1001030. PMC 2912400. PMID 20686665.

- Katzourakis A, Gifford RJ (2010). “Endogenous Viral Elements in Animal Genomes”. PLOS Genetics. 6 (11): e1001191. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1001191. PMC 2987831. PMID 21124940.

- Taylor DJ, Dittmar K, Ballinger MJ, Bruenn JA (2011). “Evolutionary maintenance of filovirus-like genes in bat genomes”. BMC Evolutionary Biology. 11 (336): 336. Bibcode:2011BMCEE..11..336T. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-11-336. PMC 3229293. PMID 22093762.

- Peters CJ, LeDuc JW (February 1999). “An Introduction to Ebola: The Virus and the Disease”. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 179 (Supplement 1): ix–xvi. doi:10.1086/514322. JSTOR 30117592. PMID 9988154.

- Plummer, Francis A.; Jones, Steven M. (2017-10-30). “The story of Canada’s Ebola vaccine”. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal. 189 (43): E1326–E1327. doi:10.1503/cmaj.170704. ISSN 0820-3946. PMC 5662448. PMID 29084758.

- Research, Center for Biologics Evaluation and (2020-01-27). “ERVEBO”. FDA.

- CZARSKA-THORLEY, Dagmara (2019-10-16). “Ervebo”. European Medicines Agency. Retrieved 2020-05-03.

- Keshwara, Rohan; Hagen, Katie R.; Abreu-Mota, Tiago; Papaneri, Amy B.; Liu, David; Wirblich, Christoph; Johnson, Reed F.; Schnell, Matthias J. (2019-03-05). “A Recombinant Rabies Virus Expressing the Marburg Virus Glycoprotein Is Dependent upon Antibody-Mediated Cellular Cytotoxicity for Protection against Marburg Virus Disease in a Murine Model”. Journal of Virology. 93 (6). doi:10.1128/JVI.01865-18. ISSN 0022-538X. PMC 6401435. PMID 30567978.

- Kelland, Kate (19 September 2014). “Scientists see risk of mutant airborne Ebola as remote”. Reuters. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- “Feature Article: New Tech Makes Detecting Airborne Ebola Virus Possible”. Department of Homeland Security. 20 April 2021. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

Further reading

- Klenk, Hans-Dieter (1999). Marburg and Ebola Viruses. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. Vol. 235. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-540-64729-4.

- Klenk, Hans-Dieter; Feldmann, Heinz (2004). Ebola and Marburg Viruses—Molecular and Cellular Biology. Wymondham, Norfolk, UK: Horizon Bioscience. ISBN 978-0-9545232-3-7.

- Kuhn, Jens H. (2008). Filoviruses—A Compendium of 40 Years of Epidemiological, Clinical, and Laboratory Studies. Archives of Virology Supplement. Vol. 20. Vienna, Austria: Springer. ISBN 978-3-211-20670-6.

- Ryabchikova, Elena I.; Price, Barbara B. (2004). Ebola and Marburg Viruses—A View of Infection Using Electron Microscopy. Columbus, Ohio, USA: Battelle Press. ISBN 978-1-57477-131-2.

- External links[edit]

- Wikimedia Commons has media related to Filoviridae.

- Wikispecies has information related to Filoviridae.

- ICTV Report: Filoviridae

- “Filoviridae“. NCBI Taxonomy Browser. 11266.

- “FILOVIR“. Scientific resources for research on filoviruses. Archived from the original on 2020-07-30. Retrieved 2014-08-08.

- Theoretical Evidence That The Ebola Virus Zaire Strain May Be Selenium-Dependent: A Factor In Pathogenesis And Viral Outbreaks? Taylor 1995

- Can Selenite Be An Ultimate Inhibitor Of Ebola And Other Viral Infections? Lipinski 2015 Archived 2020-11-19 at the Wayback Machine

- Many In West Africa May Be Immune To Ebola Virus New York Times

External links

| Cytoskeletal defects |

|---|

| Blood film findings |

|---|

| Zoonotic viral diseases (A80–B34, 042–079) |

|---|

| Taxon identifiers | Wikidata: Q46305Wikispecies: FiloviridaeCoL: 62448EoL: 5024GBIF: 7759IRMNG: 107125NCBI: 11266WoRMS: 600065 |

|---|

- Autosomal dominant disorders

- Cytoskeletal defects

- Abnormal clinical and laboratory findings for blood

- Filoviridae

- Primate diseases

- Animal viral diseases

- Biological weapons

- Hemorrhagic fevers

- Tropical diseases

- Zoonoses

- Virus families

- Muscular disorders

- Neurological disorders

- Muscular dystrophy

- Medical conditions related to obesity

- Diabetes

- Genetic diseases and disorders

Leave a Reply