The neonatal fragment crystallizable (Fc) receptor (also FcRn, IgG receptor FcRn large subunit p51, or Brambell receptor) is a protein that in humans is encoded by the FCGRT gene

It is an IgG Fc receptor which is similar in structure to the MHC class I molecule and also associates with beta-2-microglobulin. In rodents, FcRn was originally identified as the receptor that transports maternal immunoglobulin G (IgG) from mother to neonatal offspring via mother’s milk, leading to its name as the neonatal Fc receptor. In humans, FcRn is present in the placenta where it transports mother’s IgG to the growing fetus. FcRn has also been shown to play a role in regulating IgG and serum albumin turnover. Neonatal Fc receptor expression is up-regulated by the proinflammatory cytokine, TNF, and down-regulated by IFN-γ.

- Story CM, Mikulska JE, Simister NE (December 1994). “A major histocompatibility complex class I-like Fc receptor cloned from human placenta: possible role in transfer of immunoglobulin G from mother to fetus”. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 180 (6): 2377–2381. doi:10.1084/jem.180.6.2377. PMC 2191771. PMID 7964511.

- Kandil E, Egashira M, Miyoshi O, Niikawa N, Ishibashi T, Kasahara M, Miyosi O (July 1996). “The human gene encoding the heavy chain of the major histocompatibility complex class I-like Fc receptor (FCGRT) maps to 19q13.3”. Cytogenetics and Cell Genetics. 73 (1–2): 97–98. doi:10.1159/000134316. PMID 8646894.

- “Entrez Gene: FCGRT Fc fragment of IgG, receptor, transporter, alpha”.

- Simister NE, Mostov KE (1989). “Cloning and expression of the neonatal rat intestinal Fc receptor, a major histocompatibility complex class I antigen homolog”. Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology. 54 (Pt 1): 571–580. doi:10.1101/sqb.1989.054.01.068. PMID 2534798.

- Kuo TT, Aveson VG (2011-01-01). “Neonatal Fc receptor and IgG-based therapeutics”. mAbs. 3 (5): 422–430. doi:10.4161/mabs.3.5.16983. PMC 3225846. PMID 22048693.

- Rodewald R, Kraehenbuhl JP (July 1984). “Receptor-mediated transport of IgG”. The Journal of Cell Biology. 99 (1 Pt 2): 159s–164s. doi:10.1083/jcb.99.1.159s. PMC 2275593. PMID 6235233.

- Simister NE, Rees AR (July 1985). “Isolation and characterization of an Fc receptor from neonatal rat small intestine”. European Journal of Immunology. 15 (7): 733–738. doi:10.1002/eji.1830150718. PMID 2988974. S2CID 42396197.

- Firan M, Bawdon R, Radu C, Ober RJ, Eaken D, Antohe F, et al. (August 2001). “The MHC class I-related receptor, FcRn, plays an essential role in the maternofetal transfer of gamma-globulin in humans”. International Immunology. 13 (8): 993–1002. doi:10.1093/intimm/13.8.993. PMID 11470769.

- Ghetie V, Hubbard JG, Kim JK, Tsen MF, Lee Y, Ward ES (March 1996). “Abnormally short serum half-lives of IgG in beta 2-microglobulin-deficient mice”. European Journal of Immunology. 26 (3): 690–696. doi:10.1002/eji.1830260327. PMID 8605939. S2CID 85730132.

- Chaudhury C, Mehnaz S, Robinson JM, Hayton WL, Pearl DK, Roopenian DC, Anderson CL (February 2003). “The major histocompatibility complex-related Fc receptor for IgG (FcRn) binds albumin and prolongs its lifespan”. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 197 (3): 315–322. doi:10.1084/jem.20021829. PMC 2193842. PMID 12566415.

- Ghetie V, Popov S, Borvak J, Radu C, Matesoi D, Medesan C, et al. (July 1997). “Increasing the serum persistence of an IgG fragment by random mutagenesis”. Nature Biotechnology. 15 (7): 637–640. doi:10.1038/nbt0797-637. PMID 9219265. S2CID 39836528.

- Roopenian DC, Akilesh S (September 2007). “FcRn: the neonatal Fc receptor comes of age”. Nature Reviews. Immunology. 7 (9): 715–725. doi:10.1038/nri2155. PMID 17703228. S2CID 6980400.

- Ward ES, Ober RJ (2009). Chapter 4: Multitasking by exploitation of intracellular transport functions the many faces of FcRn. Advances in Immunology. Vol. 103. pp. 77–115. doi:10.1016/S0065-2776(09)03004-1. ISBN 9780123748324. PMC 4485553. PMID 19755184.

- Kuo TT, Baker K, Yoshida M, Qiao SW, Aveson VG, Lencer WI, Blumberg RS (November 2010). “Neonatal Fc receptor: from immunity to therapeutics”. Journal of Clinical Immunology. 30 (6): 777–789. doi:10.1007/s10875-010-9468-4. PMC 2970823. PMID 20886282.

Interactions of FcRn with IgG and serum albumin

In addition to binding to IgG, FCGRT has been shown to interact with human serum albumin. FcRn-mediated transcytosis of IgG across epithelial cells is possible because FcRn binds IgG at acidic pH (<6.5) but not at neutral or higher pH. The binding site for FcRn on IgG has been mapped using functional and structural studies, and involves in the interaction of relatively well conserved histidine residues on IgG with acidic residues on FcRn.

- Andersen JT, Dee Qian J, Sandlie I (November 2006). “The conserved histidine 166 residue of the human neonatal Fc receptor heavy chain is critical for the pH-dependent binding to albumin”. European Journal of Immunology. 36 (11): 3044–3051. doi:10.1002/eji.200636556. PMID 17048273. S2CID 22024929.

- Dickinson BL, Badizadegan K, Wu Z, Ahouse JC, Zhu X, Simister NE, et al. (October 1999). “Bidirectional FcRn-dependent IgG transport in a polarized human intestinal epithelial cell line”. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 104 (7): 903–911. doi:10.1172/JCI6968. PMC 408555. PMID 10510331.

- Kim JK, Tsen MF, Ghetie V, Ward ES (October 1994). “Localization of the site of the murine IgG1 molecule that is involved in binding to the murine intestinal Fc receptor”. European Journal of Immunology. 24 (10): 2429–2434. doi:10.1002/eji.1830241025. PMID 7925571. S2CID 43499403.

- Martin WL, West AP, Gan L, Bjorkman PJ (April 2001). “Crystal structure at 2.8 A of an FcRn/heterodimeric Fc complex: mechanism of pH-dependent binding”. Molecular Cell. 7 (4): 867–877. doi:10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00230-1. PMID 11336709.

- Rodewald R, Kraehenbuhl JP (July 1984). “Receptor-mediated transport of IgG”. The Journal of Cell Biology. 99 (1 Pt 2): 159s–164s. doi:10.1083/jcb.99.1.159s. PMC 2275593. PMID 6235233.

- Simister NE, Rees AR (July 1985). “Isolation and characterization of an Fc receptor from neonatal rat small intestine”. European Journal of Immunology. 15 (7): 733–738. doi:10.1002/eji.1830150718. PMID 2988974. S2CID 42396197.

- Chaudhury C, Mehnaz S, Robinson JM, Hayton WL, Pearl DK, Roopenian DC, Anderson CL (February 2003). “The major histocompatibility complex-related Fc receptor for IgG (FcRn) binds albumin and prolongs its lifespan”. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 197 (3): 315–322. doi:10.1084/jem.20021829. PMC 2193842. PMID 12566415.

FcRn-mediated recycling and transcytosis of IgG and serum albumin

FcRn extends the half-life of IgG and serum albumin by reducing lysosomal degradation of these proteins in endothelial cells and bone-marrow derived cells. The clearance rate of IgG and albumin is abnormally short in mice that lack functional FcRn. IgG, serum albumin and other serum proteins are continuously internalized into cells through pinocytosis.

In cellular biology, pinocytosis, otherwise known as fluid endocytosis and bulk-phase pinocytosis, is a mode of endocytosis in which small molecules dissolved in extracellular fluid are brought into the cell through an invagination of the cell membrane, resulting in their containment within a small vesicle inside the cell. These pinocytotic vesicles then typically fuse with early endosomes to hydrolyze (break down) the particles.[citation needed] Pinocytosis is variably subdivided into categories depending on the molecular mechanism and the fate of the internalized molecules.

Function

In humans, this process occurs primarily for absorption of fat droplets. In endocytosis the cell plasma membrane extends and folds around desired extracellular material, forming a pouch that pinches off creating an internalized vesicle. The invaginated pinocytosis vesicles are much smaller than those generated by phagocytosis. The vesicles eventually fuse with the lysosome, whereupon the vesicle contents are digested. Pinocytosis involves a considerable investment of cellular energy in the form of ATP.

- Guo, Lily. “Pinocytosis – What Is It, How It Occurs, and More”. Osmosis from Elsevier. Elsevier. Retrieved 25 December 2022.

Pinocytosis and ATP

Pinocytosis is used primarily for clearing extracellular fluids (ECF) and as part of immune surveillance. In contrast to phagocytosis, it generates very small amounts of ATP from the wastes of alternative substances such as lipids (fat).[citation needed] Unlike receptor-mediated endocytosis, pinocytosis is nonspecific in the substances that it transport: the cell takes in surrounding fluids, including all solutes present.

- Guo, Lily. “Pinocytosis – What Is It, How It Occurs, and More”. Osmosis from Elsevier. Elsevier. Retrieved 25 December 2022.

- Abbas, Abul, et al. “Basic Immunology: Functions and Disorders of the Immune System.” 5th ed. Elsevier, 2016. p.69

Etymology and pronunciation

The word pinocytosis uses combining forms of pino- + cyto- + -osis, all Neo-Latin from Greek, reflecting píno, to drink, and cytosis. The term was proposed by W. H. Lewis in 1931.

- “Pinocytosis“. Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 2019-12-23.

- “Pinocytosis“. Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Retrieved 2016-01-22.

- “Pinocytosis”. Dictionary.com Unabridged (Online). n.d. Retrieved 2016-01-22.

- Rieger, R.; Michaelis, A.; Green, M.M. 1991. Glossary of Genetics. Classical and Molecular (Fifth edition). Springer-Verlag, Berlin, [1].

Non-specific, adsorptive pinocytosis

Non-specific, adsorptive pinocytosis is a form of endocytosis, a process in which small particles are taken in by a cell by splitting off small vesicles from the cell membrane. Cationic proteins bind to the negative cell surface and are taken up via the clathrin-mediated system, thus the uptake is intermediate between receptor-mediated endocytosis and non-specific, non-adsorptive pinocytosis. The clathrin-coated pits occupy about 2% of the surface area of the cell and only last about a minute, with an estimated 2500 leaving the average cell surface each minute. The clathrin coats are lost almost immediately, and the membrane is subsequently recycled to the cell surface.

- Alberts, Johnson, Lewis, Raff, Roberts, Walter: “Molecular Biology of the Cell”, Fourth Edition, Copyright 2002 P.748

Macropinocytosis

Macropinocytosis is a clathrin-independent endocytic mechanism that can be activated in practically all animal cells, resulting in uptake. In most cell types, it does not occur continuously but rather is induced for a limited time in response to cell-surface receptor activation by specific cargoes, including growth factors, ligands of integrins, and apoptotic cell remnants. These ligands activate a complex signaling pathway, resulting in a change in actin dynamics and the formation of cell-surface protrusions of filopodia and lamellopodia, commonly called ruffles. When ruffles collapse back onto the membrane, large fluid-filled endocytic vesicles form called macropinosomes, which can transiently increase the bulk fluid uptake of a cell by up to tenfold. Macropinocytosis is a solely degradative pathway: macropinosomes acidify and then fuse with late endosomes or endolysosomes, without recycling their cargo back to the plasma membrane.

- Alberts, Bruce (2015). Molecular biology of the cell (Sixth ed.). New York, NY. p. 732. ISBN 978-0-8153-4432-2. OCLC 887605755.

Some bacteria and viruses have evolved to induce macropinocytosis as a mechanism for entering host cells. Some of these can stop the degradation processes in order to survive inside the macropinosome, which may transform into smaller and long-lasting vacuoles containing the viruses or bacteria (some of which may replicate inside), or simply escape through the wall of the macropinosome when inside. For example, the gut pathogen Salmonella typhimurium injects toxins into the host cell in order to induce macropinocytosis as a form of uptake, inhibits the degradation of the macropinosome, and forms a salmonella-containing vacuole, or SCV, wherein it can replicate.

- Pollard, Thomas D.; Earnshaw, William C.; Lippincott-Schwartz, Jennifer; Johnson, Graham T., eds. (2017-01-01), “Chapter 22 – Endocytosis and the Endosomal Membrane System”, Cell Biology (Third Edition), Elsevier, pp. 377–392, doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-34126-4.00022-0, ISBN 978-0-323-34126-4, retrieved 2022-04-12

See also

- Campbell, Reece, Mitchell: “Biology”, Sixth Edition, Copyright 2002 P. 151

- Marshall, Ben, Incredible Biological Advancements of the 20th Century, Copyright 2001 p. 899

- Alrt, Pablo, Global Society Harvard study, copyright 2003 p. 189

- Brooker, Robert: “Biology”, Second Edition, Copyright 2011 p. 116

- Cherrr, Malik, The Only Edition, Copyright 2012, p. 256

- Abbas, Abul, et al. “Basic Immunology: Functions and Disorders of the Immune System.” 5th ed. Elsevier, 2016. p. 69

Generally, internalized serum proteins are transported from early endosomes to lysosomes, where they are degraded. Following entry into cells, the two most abundant serum proteins, IgG and serum albumin, are bound by FcRn at the slightly acidic pH (<6.5) within early (sorting) endosomes, sorted and recycled to the cell surface where they are released at the neutral pH (>7.0) of the extracellular environment. In this way, IgG and serum albumin are salvaged to avoid lysosomal degradation. This cellular mechanism provides an explanation for the prolonged in vivo half-lives of IgG and serum albumin and transport of these ligands across cellular barriers. In addition, for cell types bathed in an acidic environment such as the slightly acidic intestinal lumen, cell surface FcRn can bind to IgG, transport bound ligand across intestinal epithelial cells followed by release at the near neutral pH at the basolateral surface.

- Rodewald R, Kraehenbuhl JP (July 1984). “Receptor-mediated transport of IgG”. The Journal of Cell Biology. 99 (1 Pt 2): 159s–164s. doi:10.1083/jcb.99.1.159s. PMC 2275593. PMID 6235233.

- Simister NE, Rees AR (July 1985). “Isolation and characterization of an Fc receptor from neonatal rat small intestine”. European Journal of Immunology. 15 (7): 733–738. doi:10.1002/eji.1830150718. PMID 2988974. S2CID 42396197.

- Firan M, Bawdon R, Radu C, Ober RJ, Eaken D, Antohe F, et al. (August 2001). “The MHC class I-related receptor, FcRn, plays an essential role in the maternofetal transfer of gamma-globulin in humans”. International Immunology. 13 (8): 993–1002. doi:10.1093/intimm/13.8.993. PMID 11470769.

- Ghetie V, Hubbard JG, Kim JK, Tsen MF, Lee Y, Ward ES (March 1996). “Abnormally short serum half-lives of IgG in beta 2-microglobulin-deficient mice”. European Journal of Immunology. 26 (3): 690–696. doi:10.1002/eji.1830260327. PMID 8605939. S2CID 85730132.

- Chaudhury C, Mehnaz S, Robinson JM, Hayton WL, Pearl DK, Roopenian DC, Anderson CL (February 2003). “The major histocompatibility complex-related Fc receptor for IgG (FcRn) binds albumin and prolongs its lifespan”. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 197 (3): 315–322. doi:10.1084/jem.20021829. PMC 2193842. PMID 12566415.

- Roopenian DC, Akilesh S (September 2007). “FcRn: the neonatal Fc receptor comes of age”. Nature Reviews. Immunology. 7 (9): 715–725. doi:10.1038/nri2155. PMID 17703228. S2CID 6980400.

- Ward ES, Ober RJ (2009). Chapter 4: Multitasking by exploitation of intracellular transport functions the many faces of FcRn. Advances in Immunology. Vol. 103. pp. 77–115. doi:10.1016/S0065-2776(09)03004-

- Dickinson BL, Badizadegan K, Wu Z, Ahouse JC, Zhu X, Simister NE, et al. (October 1999). “Bidirectional FcRn-dependent IgG transport in a polarized human intestinal epithelial cell line”. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 104 (7): 903–911. doi:10.1172/JCI6968. PMC 408555. PMID 10510331.

- Ward ES, Zhou J, Ghetie V, Ober RJ (February 2003). “Evidence to support the cellular mechanism involved in serum IgG homeostasis in humans”. International Immunology. 15 (2): 187–195. doi:10.1093/intimm/dxg018. PMID 12578848.

- Akilesh S, Christianson GJ, Roopenian DC, Shaw AS (October 2007). “Neonatal FcR expression in bone marrow-derived cells functions to protect serum IgG from catabolism”. Journal of Immunology. 179 (7): 4580–4588. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.179.7.4580. PMID 17878355.

- Qiao SW, Kobayashi K, Johansen FE, Sollid LM, Andersen JT, Milford E, et al. (July 2008). “Dependence of antibody-mediated presentation of antigen on FcRn”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 105 (27): 9337–9342. Bibcode:2008PNAS..105.9337Q. doi:10.1073/pnas.0801717105. PMC 2453734. PMID 18599440.

- Montoyo HP, Vaccaro C, Hafner M, Ober RJ, Mueller W, Ward ES (February 2009). “Conditional deletion of the MHC class I-related receptor FcRn reveals the sites of IgG homeostasis in mice”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (8): 2788–2793. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.2788M. doi:10.1073/pnas.0810796106. PMC 2650344. PMID 19188594.

- Ober RJ, Martinez C, Vaccaro C, Zhou J, Ward ES (February 2004). “Visualizing the site and dynamics of IgG salvage by the MHC class I-related receptor, FcRn”. Journal of Immunology. 172 (4): 2021–2029. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.172.4.2021. PMID 14764666. S2CID 30526875.

- Ober RJ, Martinez C, Lai X, Zhou J, Ward ES (July 2004). “Exocytosis of IgG as mediated by the receptor, FcRn: an analysis at the single-molecule level”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 101 (30): 11076–11081. Bibcode:2004PNAS..10111076O. doi:10.1073/pnas.0402970101. PMC 503743. PMID 15258288.

- Prabhat P, Gan Z, Chao J, Ram S, Vaccaro C, Gibbons S, et al. (April 2007). “Elucidation of intracellular recycling pathways leading to exocytosis of the Fc receptor, FcRn, by using multifocal plane microscopy”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 104 (14): 5889–5894. doi:10.1073/pnas.0700337104. PMC 1851587. PMID 17384151.

- Larsen MT, Rawsthorne H, Schelde KK, Dagnæs-Hansen F, Cameron J, Howard KA (October 2018). “Cellular recycling-driven in vivo half-life extension using recombinant albumin fusions tuned for neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn) engagement”. Journal of Controlled Release. 287: 132–141. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2018.07.023. PMID 30016735. S2CID 51677989.

- Spiekermann GM, Finn PW, Ward ES, Dumont J, Dickinson BL, Blumberg RS, Lencer WI (August 2002). “Receptor-mediated immunoglobulin G transport across mucosal barriers in adult life: functional expression of FcRn in the mammalian lung”. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 196 (3): 303–310. doi:10.1084/jem.20020400. PMC 2193935. PMID 12163559.

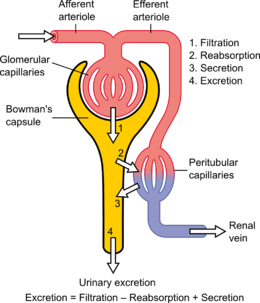

Diverse roles for FcRn in various organs

FcRn is expressed on antigen-presenting leukocytes such as dendritic cells and is also expressed in neutrophils to help clear opsonized bacteria. In the kidneys, FcRn is expressed on epithelial cells called podocytes to prevent IgG and albumin from clogging the glomerular filtration barrier. Current studies are investigating FcRn in the liver because there are relatively low concentrations of both IgG and albumin in liver bile despite high concentrations in the blood. Studies have also shown that FcRn-mediated transcytosis is involved with the trafficking of the HIV-1 virus across genital tract epithelium.

- Kuo TT, Baker K, Yoshida M, Qiao SW, Aveson VG, Lencer WI, Blumberg RS (November 2010). “Neonatal Fc receptor: from immunity to therapeutics”. Journal of Clinical Immunology. 30 (6): 777–789. doi:10.1007/s10875-010-9468-4. PMC 2970823. PMID 20886282.

- Akilesh S, Huber TB, Wu H, Wang G, Hartleben B, Kopp JB, et al. (January 2008). “Podocytes use FcRn to clear IgG from the glomerular basement membrane”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 105 (3): 967–972. doi:10.1073/pnas.0711515105. PMC 2242706. PMID 18198272.

- Bern M, Sand KM, Nilsen J, Sandlie I, Andersen JT (August 2015). “The role of albumin receptors in regulation of albumin homeostasis: Implications for drug delivery”. Journal of Controlled Release. 211: 144–162. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.06.006. PMID 26055641. S2CID 205878058.

- Sand KM, Bern M, Nilsen J, Noordzij HT, Sandlie I, Andersen JT (2015-01-26). “Unraveling the Interaction between FcRn and Albumin: Opportunities for Design of Albumin-Based Therapeutics”. Frontiers in Immunology. 5: 682. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2014.00682. PMC 4306297. PMID 25674083.

- Pyzik M, Rath T, Kuo TT, Win S, Baker K, Hubbard JJ, et al. (April 2017). “Hepatic FcRn regulates albumin homeostasis and susceptibility to liver injury”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 114 (14): E2862–E2871. doi:10.1073/pnas.1618291114. PMC 5389309. PMID 28330995.

- Gupta S, Gach JS, Becerra JC, Phan TB, Pudney J, Moldoveanu Z, et al. (2013-11-01). “The Neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn) enhances human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) transcytosis across epithelial cells”. PLOS Pathogens. 9 (11): e1003776. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1003776. PMC 3836734. PMID 24278022.

Podocytes are cells in Bowman’s capsule in the kidneys that wrap around capillaries of the glomerulus. Podocytes make up the epithelial lining of Bowman’s capsule, the third layer through which filtration of blood takes place. Bowman’s capsule filters the blood, retaining large molecules such as proteins while smaller molecules such as water, salts, and sugars are filtered as the first step in the formation of urine. Although various viscera have epithelial layers, the name visceral epithelial cells usually refers specifically to podocytes, which are specialized epithelial cells that reside in the visceral layer of the capsule. The podocytes have long foot processes called pedicels, for which the cells are named (podo- + -cyte). The pedicels wrap around the capillaries and leave slits between them. Blood is filtered through these slits, each known as a filtration slit, slit diaphragm, or slit pore. Several proteins are required for the pedicels to wrap around the capillaries and function. When infants are born with certain defects in these proteins, such as nephrin and CD2AP, their kidneys cannot function. People have variations in these proteins, and some variations may predispose them to kidney failure later in life. Nephrin is a zipper-like protein that forms the slit diaphragm, with spaces between the teeth of the zipper big enough to allow sugar and water through but too small to allow proteins through. Nephrin defects are responsible for congenital kidney failure. CD2AP regulates the podocyte cytoskeleton and stabilizes the slit diaphragm.

- “Podocyte” at Dorland’s Medical Dictionary

- Lote CJ (2012). “Glomerular Filtration”. Principles of Renal Physiology (5th ed.). New York: Springer Science+Business Media. p. 34. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-3785-7_3. ISBN 978-1-4614-3784-0.

- Wickelgren I (October 1999). “First components found for new kidney filter”. Science. 286 (5438): 225–226. doi:10.1126/science.286.5438.225. PMID 10577188. S2CID 43237744.

- Löwik MM, Groenen PJ, Levtchenko EN, Monnens LA, van den Heuvel LP (November 2009). “Molecular genetic analysis of podocyte genes in focal segmental glomerulosclerosis–a review”. European Journal of Pediatrics. 168 (11): 1291–1304. doi:10.1007/s00431-009-1017-x. PMC 2745545. PMID 19562370.

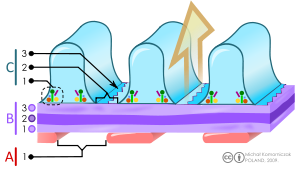

Structure

Podocytes are found lining the Bowman’s capsules in the nephrons of the kidney. The foot processes known as pedicels that extend from the podocytes wrap themselves around the capillaries of the glomerulus to form the filtration slits. The pedicels increase the surface area of the cells enabling efficient ultrafiltration. Podocytes secrete and maintain the basement membrane.

- Nosek TM. “Epithelium; Cell Types”. Essentials of Human Physiology. Archived from the original on 24 March 2016.

- Lote CJ (2012). “Glomerular Filtration”. Principles of Renal Physiology (5th ed.). New York: Springer Science+Business Media. p. 34. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-3785-7_3. ISBN 978-1-4614-3784-0.

A. The endothelial cells of the glomerulus; 1. pore (fenestra).

B. Glomerular basement membrane: 1. lamina rara interna 2. lamina densa 3. lamina rara externa

C. Podocytes: 1. enzymatic and structural protein 2. filtration slit 3. diaphragma

There are numerous coated vesicles and coated pits along the basolateral domain of the podocytes which indicate a high rate of vesicular traffic. Podocytes possess a well-developed endoplasmic reticulum and a large Golgi apparatus, indicative of a high capacity for protein synthesis and post-translational modifications. There is also growing evidence of a large number of multivesicular bodies and other lysosomal components seen in these cells, indicating a high endocytic activity.

Function

Podocytes have primary processes called trabeculae, which wrap around the glomerular capillaries. The trabeculae in turn have secondary processes called pedicels. Pedicels interdigitate, thereby giving rise to thin gaps called filtration slits. The slits are covered by slit diaphragms which are composed of a number of cell-surface proteins including nephrin, podocalyxin, and P-cadherin, which restrict the passage of large macromolecules such as serum albumin and gamma globulin and ensure that they remain in the bloodstream. Proteins that are required for the correct function of the slit diaphragm include nephrin, NEPH1, NEPH2, podocin, CD2AP. and FAT1.

- Lote CJ (2012). “Glomerular Filtration”. Principles of Renal Physiology (5th ed.). New York: Springer Science+Business Media. p. 34. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-3785-7_3. ISBN 978-1-4614-3784-0.

- Ovalle WK, Nahirney PC (28 February 2013). Netter’s Essential Histology E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 978-1-4557-0307-4. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- Jarad G, Miner JH (May 2009). “Update on the glomerular filtration barrier”. Current Opinion in Nephrology and Hypertension. 18 (3): 226–232. doi:10.1097/mnh.0b013e3283296044. PMC 2895306. PMID 19374010.

- Wartiovaara J, Ofverstedt LG, Khoshnoodi J, Zhang J, Mäkelä E, Sandin S, et al. (November 2004). “Nephrin strands contribute to a porous slit diaphragm scaffold as revealed by electron tomography”. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 114 (10): 1475–1483. doi:10.1172/JCI22562. PMC 525744. PMID 15545998.

- Neumann-Haefelin E, Kramer-Zucker A, Slanchev K, Hartleben B, Noutsou F, Martin K, et al. (June 2010). “A model organism approach: defining the role of Neph proteins as regulators of neuron and kidney morphogenesis”. Human Molecular Genetics. 19 (12): 2347–2359. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddq108. PMID 20233749.

- Fukasawa H, Bornheimer S, Kudlicka K, Farquhar MG (July 2009). “Slit diaphragms contain tight junction proteins”. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 20 (7): 1491–1503. doi:10.1681/ASN.2008101117. PMC 2709684. PMID 19478094.

- Ciani L, Patel A, Allen ND, ffrench-Constant C (May 2003). “Mice lacking the giant protocadherin mFAT1 exhibit renal slit junction abnormalities and a partially penetrant cyclopia and anophthalmia phenotype”. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 23 (10): 3575–3582. doi:10.1128/mcb.23.10.3575-3582.2003. PMC 164754. PMID 12724416.

Small molecules such as water, glucose, and ionic salts are able to pass through the filtration slits and form an ultrafiltrate in the tubular fluid, which is further processed by the nephron to produce urine. Podocytes are also involved in regulation of glomerular filtration rate (GFR). When podocytes contract, they cause closure of filtration slits. This decreases the GFR by reducing the surface area available for filtration.

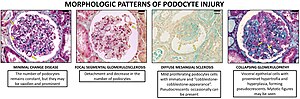

Clinical significance

– CC-BY 4.0 license

A loss of the foot processes of the podocytes (i.e., podocyte effacement) is a hallmark of minimal change disease, which has therefore sometimes been called foot process disease.

- Vivarelli M, Massella L, Ruggiero B, Emma F (February 2017). “Minimal Change Disease”. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 12 (2): 332–345. doi:10.2215/CJN.05000516. PMC 5293332. PMID 27940460.

Disruption of the filtration slits or destruction of the podocytes can lead to massive proteinuria, where large amounts of protein are lost from the blood. An example of this occurs in the congenital disorder Finnish-type nephrosis, which is characterised by neonatal proteinuria leading to end-stage kidney failure. This disease has been found to be caused by a mutation in the nephrin gene.

In 2002 Professor Moin Saleem at the University of Bristol made the first conditionally immortalised human podocyte cell line.[further explanation needed] This meant that podocytes could be grown and studied in the lab. Since then many discoveries have been made. Nephrotic syndrome occurs when there is a breakdown of the glomerular filtration barrier. The podocytes form one layer of the filtration barrier. Genetic mutations can cause podocyte dysfunction leading to an inability of the filtration barrier to restrict urinary protein loss. There are currently 53 genes known to play a role in genetic nephrotic syndrome. In idiopathic nephrotic syndrome, there is no known genetic mutation. It is thought to be caused by a hitherto unknown circulating permeability factor. Recent evidence suggests that the factor could be released by T-cells or B-cells, podocyte cell lines can be treated with plasma from patients with nephrotic syndrome to understand the specific responses of the podocyte to the circulating factor. There is growing evidence that the circulating factor could be signalling to the podocyte via the PAR-1 receptor.[further explanation needed]

- Saleem, Moin A.; O’Hare, Michael J.; Reiser, Jochen; Coward, Richard J.; Inward, Carol D.; Farren, Timothy; Xing, Chang Ying; Ni, Lan; Mathieson, Peter W.; Mundel, Peter (March 2002). “A conditionally immortalized human podocyte cell line demonstrating nephrin and podocin expression”. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 13 (3): 630–638. doi:10.1681/ASN.V133630. ISSN 1046-6673. PMID 11856766.

- Bierzynska, Agnieszka; McCarthy, Hugh J.; Soderquest, Katrina; Sen, Ethan S.; Colby, Elizabeth; Ding, Wen Y.; Nabhan, Marwa M.; Kerecuk, Larissa; Hegde, Shivram; Hughes, David; Marks, Stephen; Feather, Sally; Jones, Caroline; Webb, Nicholas J. A.; Ognjanovic, Milos (April 2017). “Genomic and clinical profiling of a national nephrotic syndrome cohort advocates a precision medicine approach to disease management”. Kidney International. 91 (4): 937–947. doi:10.1016/j.kint.2016.10.013. hdl:1983/c730c0d6-5527-435a-8c27-a99fd990a0e8. ISSN 1523-1755. PMID 28117080. S2CID 4768411.

- Maas, Rutger J.; Deegens, Jeroen K.; Wetzels, Jack F. (2014). “Permeability factors in idiopathic nephrotic syndrome: historical perspectives and lessons for the future”. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. academic.oup.com. 29 (12): 2207–2216. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfu355. Retrieved 26 April 2023.

- Hackl, Agnes; Zed, Seif El Din Abo; Diefenhardt, Paul; Binz-Lotter, Julia; Ehren, Rasmus; Weber, Lutz Thorsten (18 November 2021). “The role of the immune system in idiopathic nephrotic syndrome”. Molecular and Cellular Pediatrics. 8 (1): 18. doi:10.1186/s40348-021-00128-6. ISSN 2194-7791. PMC 8600105. PMID 34792685.

- May, Carl J.; Welsh, Gavin I.; Chesor, Musleeha; Lait, Phillipa J.; Schewitz-Bowers, Lauren P.; Lee, Richard W. J.; Saleem, Moin A. (1 October 2019). “Human Th17 cells produce a soluble mediator that increases podocyte motility via signaling pathways that mimic PAR-1 activation”. American Journal of Physiology. Renal Physiology. 317 (4): F913–F921. doi:10.1152/ajprenal.00093.2019. ISSN 1522-1466. PMC 6843047. PMID 31339775.

- May, Carl J.; Chesor, Musleeha; Hunter, Sarah E.; Hayes, Bryony; Barr, Rachel; Roberts, Tim; Barrington, Fern A.; Farmer, Louise; Ni, Lan; Jackson, Maisie; Snethen, Heidi; Tavakolidakhrabadi, Nadia; Goldstone, Max; Gilbert, Rodney; Beesley, Matt (March 2023). “Podocyte protease activated receptor 1 stimulation in mice produces focal segmental glomerulosclerosis mirroring human disease signaling events”. Kidney International. 104 (2): 265–278. doi:10.1016/j.kint.2023.02.031. ISSN 0085-2538. PMID 36940798. S2CID 257639270.

Presence of podocytes in urine has been proposed as an early diagnostic marker for preeclampsia.

- Konieczny A, Ryba M, Wartacz J, Czyżewska-Buczyńska A, Hruby Z, Witkiewicz W (2013). “Podocytes in urine, a novel biomarker of preeclampsia?“ (PDF). Advances in Clinical and Experimental Medicine. 22 (2): 145–149. PMID 23709369.

See also

- List of human cell types derived from the germ layers

- List of distinct cell types in the adult human body

Half-life extension of therapeutic proteins

The identification of FcRn as a central regulator of IgG levels led to the engineering of IgG-FcRn interactions to increase in vivo persistence of IgG. For example, the half-life extended complement C5-specific antibody, Ultomiris (ravulizumab), has been approved for the treatment of autoimmunity and a half-life extended antibody cocktail (Evusheld) with ‘YTE’ mutations is used for the prophylaxis of SARS-CoV2. Engineering of albumin-FcRn interactions has also generated albumin variants with increased in vivo half-lives. It has also been shown that conjugation of some drugs to the Fc region of IgG or serum albumin to generate fusion proteins significantly increases their half-life.

- Ghetie V, Hubbard JG, Kim JK, Tsen MF, Lee Y, Ward ES (March 1996). “Abnormally short serum half-lives of IgG in beta 2-microglobulin-deficient mice”. European Journal of Immunology. 26 (3): 690–696. doi:10.1002/eji.1830260327. PMID 8605939. S2CID

- Ghetie V, Popov S, Borvak J, Radu C, Matesoi D, Medesan C, et al. (July 1997). “Increasing the serum persistence of an IgG fragment by random mutagenesis”. Nature Biotechnology. 15 (7):

- Ward ES, Ober RJ (October 2018). “Targeting FcRn to Generate Antibody-Based Therapeutics”. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 39 (10): 892–904. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2018.07.007. PMC 6169532. PMID 30143244.

- “Ultomiris® (ravulizumab-cwvz) | Alexion”. Retrieved 2021-10-03.

- Dall’Acqua WF, Woods RM, Ward ES, Palaszynski SR, Patel NK, Brewah YA, et al. (November 2002). “Increasing the affinity of a human IgG1 for the neonatal Fc receptor: biological consequences”. Journal of Immunology. 169 (9): 5171–5180. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.169.9.5171. PMID 12391234. S2CID 29398244.

- “Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: FDA Authorizes New Long-Acting Monoclonal Antibodies for Pre-exposure Prevention of COVID-19 in Certain Individuals”. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 8 December 2021.

- Andersen JT, Dalhus B, Viuff D, Ravn BT, Gunnarsen KS, Plumridge A, et al. (May 2014). “Extending serum half-life of albumin by engineering neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn) binding”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 289 (19): 13492–13502. doi:10.1074/jbc.M114.549832. PMC 4036356. PMID 24652290.

- Lee TY, Tjin Tham Sjin RM, Movahedi S, Ahmed B, Pravda EA, Lo KM, et al. (March 2008). “Linking antibody Fc domain to endostatin significantly improves endostatin half-life and efficacy”. Clinical Cancer Research. 14 (5): 1487–1493. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1530. PMID 18316573.

- Poznansky MJ, Halford J, Taylor D (October 1988). “Growth hormone-albumin conjugates. Reduced renal toxicity and altered plasma clearance”. FEBS Letters. 239 (1): 18–22. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(88)80537-4. PMID 3181423. S2CID 38592689.

- Strohl WR (August 2015). “Fusion Proteins for Half-Life Extension of Biologics as a Strategy to Make Biobetters”. BioDrugs. 29 (4): 215–239. doi:10.1007/s40259-015-0133-6. PMC 4562006. PMID 26177629.

- 637–640. doi:10.1038/nbt0797-637. PMID 9219265. S2CID 39836528.

There are several drugs on the market that have Fc portions fused to the effector proteins in order to increase their half-lives through FcRn-mediated recycling. They include: Amevive (alefacept), Arcalyst (rilonacept), Enbrel (etanercept), Nplate (romiplostim), Orencia (abatacept) and Nulojix (belatacept). Enbrel (etanercept) was the first successful IgG Fc-linked soluble receptor therapeutic and works by binding and neutralizing the pro-inflammatory cytokine, TNF-α.

- Strohl WR (August 2015). “Fusion Proteins for Half-Life Extension of Biologics as a Strategy to Make Biobetters”. BioDrugs. 29 (4): 215–239. doi:10.1007/s40259-015-0133-6. PMC 4562006. PMID 26177629.

- Goldenberg MM (January 1999). “Etanercept, a novel drug for the treatment of patients with severe, active rheumatoid arthritis”. Clinical Therapeutics. 21 (1): 75–87, discussion 1–2. doi:10.1016/S0149-2918(00)88269-7. PMID 10090426.

Targeting FcRn to treat autoimmune disease

Multiple autoimmune disorders are caused by the binding of IgG to self antigens. Since FcRn extends IgG half-life in the circulation, it can also confer long half-lives on these pathogenic antibodies and promote autoimmune disease. Therapies seek to disrupt the IgG-FcRn interaction to increase the clearance of disease-causing IgG autoantibodies from the body. One such therapy is the infusion of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) to saturate FcRn’s IgG recycling capacity and proportionately reduce the levels of disease-causing IgG autoantibody binding to FcRn, thereby increasing disease-causing IgG autoantibody removal. More recent approaches involve the strategy of blocking the binding of IgG to FcRn by delivering antibodies that bind with high affinity to this receptor through their Fc region or variable regions. These engineered Fc fragments or antibodies are being used in clinical trials as treatments for antibody-mediated autoimmune diseases such as primary immune thrombocytopenia and skin blistering diseases (pemphigus), and the Fc-based inhibitor, efgartigimod, based on the ‘Abdeg’ technology was recently approved (as ‘Vyvgart’) for the treatment of generalized MYASTHENIA GRAVIS in December 2021.

- Akilesh S, Petkova S, Sproule TJ, Shaffer DJ, Christianson GJ, Roopenian D (May 2004). “The MHC class I-like Fc receptor promotes humorally mediated autoimmune disease”. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 113 (9): 1328–1333. doi:10.1172/JCI18838. PMC 398424. PMID 15124024.

- Hansen RJ, Balthasar JP (June 2003). “Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic modeling of the effects of intravenous immunoglobulin on the disposition of antiplatelet antibodies in a rat model of immune thrombocytopenia”. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 92 (6): 1206–1215. doi:10.1002/jps.10364. PMID 12761810.

- Patel DA, Puig-Canto A, Challa DK, Perez Montoyo H, Ober RJ, Ward ES (July 2011). “Neonatal Fc receptor blockade by Fc engineering ameliorates arthritis in a murine model”. Journal of Immunology. 187 (2): 1015–1022. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1003780. PMC 3157913. PMID 21690327.

- Sockolosky JT, Szoka FC (August 2015). “The neonatal Fc receptor, FcRn, as a target for drug delivery and therapy”. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. Editor’s Collection 2015. 91: 109–124. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2015.02.005. PMC 4544678. PMID 25703189.

- Nimmerjahn F, Ravetch JV (2008-01-01). “Anti-inflammatory actions of intravenous immunoglobulin”. Annual Review of Immunology. 26 (1): 513–533. doi:10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090232. PMID 18370923.

- Vaccaro C, Zhou J, Ober RJ, Ward ES (October 2005). “Engineering the Fc region of immunoglobulin G to modulate in vivo antibody levels”. Nature Biotechnology. 23 (10): 1283–1288. doi:10.1038/nbt1143. PMID 16186811. S2CID 13526188.

- Ulrichts P, Guglietta A, Dreier T, van Bragt T, Hanssens V, Hofman E, et al. (October 2018). “Neonatal Fc receptor antagonist efgartigimod safely and sustainably reduces IgGs in humans”. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 128 (10): 4372–4386. doi:10.1172/JCI97911. PMC 6159959. PMID 30040076.

- Nixon AE, Chen J, Sexton DJ, Muruganandam A, Bitonti AJ, Dumont J, et al. (2015). “Fully human monoclonal antibody inhibitors of the neonatal fc receptor reduce circulating IgG in non-human primates”. Frontiers in Immunology. 6: 176. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2015.00176. PMC 4407741. PMID 25954273.

- Kiessling P, Lledo-Garcia R, Watanabe S, Langdon G, Tran D, Bari M, et al. (November 2017). “The FcRn inhibitor rozanolixizumab reduces human serum IgG concentration: A randomized phase 1 study”. Science Translational Medicine. 9 (414): eaan1208. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aan1208. PMID 29093180. S2CID 206694327.

- Blumberg LJ, Humphries JE, Jones SD, Pearce LB, Holgate R, Hearn A, et al. (December 2019). “Blocking FcRn in humans reduces circulating IgG levels and inhibits IgG immune complex-mediated immune responses”. Science Advances. 5 (12): eaax9586. Bibcode:2019SciA….5.9586B. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aax9586. PMC 6920022. PMID 31897428.

- Newland AC, Sánchez-González B, Rejtő L, Egyed M, Romanyuk N, Godar M, et al. (February 2020). “Phase 2 study of efgartigimod, a novel FcRn antagonist, in adult patients with primary immune thrombocytopenia”. American Journal of Hematology. 95 (2): 178–187. doi:10.1002/ajh.25680. PMC 7004056. PMID 31821591.

- Robak T, Kaźmierczak M, Jarque I, Musteata V, Treliński J, Cooper N, et al. (September 2020). “Phase 2 multiple-dose study of an FcRn inhibitor, rozanolixizumab, in patients with primary immune thrombocytopenia”. Blood Advances. 4 (17): 4136–4146. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2020002003. PMC 7479959. PMID 32886753.

- Werth VP, Culton DA, Concha JS, Graydon JS, Blumberg LJ, Okawa J, et al. (December 2021). “Safety, Tolerability, and Activity of ALXN1830 Targeting the Neonatal Fc Receptor in Chronic Pemphigus”. The Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 141 (12): 2858–2865.e4. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2021.04.031. PMID 34126109. S2CID 235439165.

- Goebeler M, Bata-Csörgő Z, De Simone C, Didona B, Remenyik E, Reznichenko N, et al. (October 2021). “Treatment of pemphigus vulgaris and foliaceus with efgartigimod, a neonatal Fc receptor inhibitor: a phase II multicentre, open-label feasibility trial”. The British Journal of Dermatology. 186 (3): 429–439. doi:10.1111/bjd.20782. hdl:2437/328911. PMID 34608631. S2CID 238355823.

- “argenx Announces U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Approval of VYVGART™ (efgartigimod alfa-fcab) in Generalized Myasthenia Gravis”. Argenx. 17 December 2021.

References

- Story CM, Mikulska JE, Simister NE (December 1994). “A major histocompatibility complex class I-like Fc receptor cloned from human placenta: possible role in transfer of immunoglobulin G from mother to fetus”. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 180 (6): 2377–2381. doi:10.1084/jem.180.6.2377. PMC 2191771. PMID 7964511.

- Kandil E, Egashira M, Miyoshi O, Niikawa N, Ishibashi T, Kasahara M, Miyosi O (July 1996). “The human gene encoding the heavy chain of the major histocompatibility complex class I-like Fc receptor (FCGRT) maps to 19q13.3”. Cytogenetics and Cell Genetics. 73 (1–2): 97–98. doi:10.1159/000134316. PMID 8646894.

- “Entrez Gene: FCGRT Fc fragment of IgG, receptor, transporter, alpha”.

- Simister NE, Mostov KE (1989). “Cloning and expression of the neonatal rat intestinal Fc receptor, a major histocompatibility complex class I antigen homolog”. Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology. 54 (Pt 1): 571–580. doi:10.1101/sqb.1989.054.01.068. PMID 2534798.

- Kuo TT, Aveson VG (2011-01-01). “Neonatal Fc receptor and IgG-based therapeutics”. mAbs. 3 (5): 422–430. doi:10.4161/mabs.3.5.16983. PMC 3225846. PMID 22048693.

- Rodewald R, Kraehenbuhl JP (July 1984). “Receptor-mediated transport of IgG”. The Journal of Cell Biology. 99 (1 Pt 2): 159s–164s. doi:10.1083/jcb.99.1.159s. PMC 2275593. PMID 6235233.

- Simister NE, Rees AR (July 1985). “Isolation and characterization of an Fc receptor from neonatal rat small intestine”. European Journal of Immunology. 15 (7): 733–738. doi:10.1002/eji.1830150718. PMID 2988974. S2CID 42396197.

- Firan M, Bawdon R, Radu C, Ober RJ, Eaken D, Antohe F, et al. (August 2001). “The MHC class I-related receptor, FcRn, plays an essential role in the maternofetal transfer of gamma-globulin in humans”. International Immunology. 13 (8): 993–1002. doi:10.1093/intimm/13.8.993. PMID 11470769.

- Ghetie V, Hubbard JG, Kim JK, Tsen MF, Lee Y, Ward ES (March 1996). “Abnormally short serum half-lives of IgG in beta 2-microglobulin-deficient mice”. European Journal of Immunology. 26 (3): 690–696. doi:10.1002/eji.1830260327. PMID 8605939. S2CID 85730132.

- Chaudhury C, Mehnaz S, Robinson JM, Hayton WL, Pearl DK, Roopenian DC, Anderson CL (February 2003). “The major histocompatibility complex-related Fc receptor for IgG (FcRn) binds albumin and prolongs its lifespan”. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 197 (3): 315–322. doi:10.1084/jem.20021829. PMC 2193842. PMID 12566415.

- Ghetie V, Popov S, Borvak J, Radu C, Matesoi D, Medesan C, et al. (July 1997). “Increasing the serum persistence of an IgG fragment by random mutagenesis”. Nature Biotechnology. 15 (7): 637–640. doi:10.1038/nbt0797-637. PMID 9219265. S2CID 39836528.

- Roopenian DC, Akilesh S (September 2007). “FcRn: the neonatal Fc receptor comes of age”. Nature Reviews. Immunology. 7 (9): 715–725. doi:10.1038/nri2155. PMID 17703228. S2CID 6980400.

- Ward ES, Ober RJ (2009). Chapter 4: Multitasking by exploitation of intracellular transport functions the many faces of FcRn. Advances in Immunology. Vol. 103. pp. 77–115. doi:10.1016/S0065-2776(09)03004-1. ISBN 9780123748324. PMC 4485553. PMID 19755184.

- Kuo TT, Baker K, Yoshida M, Qiao SW, Aveson VG, Lencer WI, Blumberg RS (November 2010). “Neonatal Fc receptor: from immunity to therapeutics”. Journal of Clinical Immunology. 30 (6): 777–789. doi:10.1007/s10875-010-9468-4. PMC 2970823. PMID 20886282.

- Andersen JT, Dee Qian J, Sandlie I (November 2006). “The conserved histidine 166 residue of the human neonatal Fc receptor heavy chain is critical for the pH-dependent binding to albumin”. European Journal of Immunology. 36 (11): 3044–3051. doi:10.1002/eji.200636556. PMID 17048273. S2CID 22024929.

- Dickinson BL, Badizadegan K, Wu Z, Ahouse JC, Zhu X, Simister NE, et al. (October 1999). “Bidirectional FcRn-dependent IgG transport in a polarized human intestinal epithelial cell line”. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 104 (7): 903–911. doi:10.1172/JCI6968. PMC 408555. PMID 10510331.

- Kim JK, Tsen MF, Ghetie V, Ward ES (October 1994). “Localization of the site of the murine IgG1 molecule that is involved in binding to the murine intestinal Fc receptor”. European Journal of Immunology. 24 (10): 2429–2434. doi:10.1002/eji.1830241025. PMID 7925571. S2CID 43499403.

- Martin WL, West AP, Gan L, Bjorkman PJ (April 2001). “Crystal structure at 2.8 A of an FcRn/heterodimeric Fc complex: mechanism of pH-dependent binding”. Molecular Cell. 7 (4): 867–877. doi:10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00230-1. PMID 11336709.

- Ward ES, Zhou J, Ghetie V, Ober RJ (February 2003). “Evidence to support the cellular mechanism involved in serum IgG homeostasis in humans”. International Immunology. 15 (2): 187–195. doi:10.1093/intimm/dxg018. PMID 12578848.

- Akilesh S, Christianson GJ, Roopenian DC, Shaw AS (October 2007). “Neonatal FcR expression in bone marrow-derived cells functions to protect serum IgG from catabolism”. Journal of Immunology. 179 (7): 4580–4588. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.179.7.4580. PMID 17878355.

- Qiao SW, Kobayashi K, Johansen FE, Sollid LM, Andersen JT, Milford E, et al. (July 2008). “Dependence of antibody-mediated presentation of antigen on FcRn”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 105 (27): 9337–9342. Bibcode:2008PNAS..105.9337Q. doi:10.1073/pnas.0801717105. PMC 2453734. PMID 18599440.

- Montoyo HP, Vaccaro C, Hafner M, Ober RJ, Mueller W, Ward ES (February 2009). “Conditional deletion of the MHC class I-related receptor FcRn reveals the sites of IgG homeostasis in mice”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (8): 2788–2793. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.2788M. doi:10.1073/pnas.0810796106. PMC 2650344. PMID 19188594.

- Ober RJ, Martinez C, Vaccaro C, Zhou J, Ward ES (February 2004). “Visualizing the site and dynamics of IgG salvage by the MHC class I-related receptor, FcRn”. Journal of Immunology. 172 (4): 2021–2029. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.172.4.2021. PMID 14764666. S2CID 30526875.

- Ober RJ, Martinez C, Lai X, Zhou J, Ward ES (July 2004). “Exocytosis of IgG as mediated by the receptor, FcRn: an analysis at the single-molecule level”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 101 (30): 11076–11081. Bibcode:2004PNAS..10111076O. doi:10.1073/pnas.0402970101. PMC 503743. PMID 15258288.

- Prabhat P, Gan Z, Chao J, Ram S, Vaccaro C, Gibbons S, et al. (April 2007). “Elucidation of intracellular recycling pathways leading to exocytosis of the Fc receptor, FcRn, by using multifocal plane microscopy”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 104 (14): 5889–5894. doi:10.1073/pnas.0700337104. PMC 1851587. PMID 17384151.

- Larsen MT, Rawsthorne H, Schelde KK, Dagnæs-Hansen F, Cameron J, Howard KA (October 2018). “Cellular recycling-driven in vivo half-life extension using recombinant albumin fusions tuned for neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn) engagement”. Journal of Controlled Release. 287: 132–141. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2018.07.023. PMID 30016735. S2CID 51677989.

- Spiekermann GM, Finn PW, Ward ES, Dumont J, Dickinson BL, Blumberg RS, Lencer WI (August 2002). “Receptor-mediated immunoglobulin G transport across mucosal barriers in adult life: functional expression of FcRn in the mammalian lung”. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 196 (3): 303–310. doi:10.1084/jem.20020400. PMC 2193935. PMID 12163559.

- Akilesh S, Huber TB, Wu H, Wang G, Hartleben B, Kopp JB, et al. (January 2008). “Podocytes use FcRn to clear IgG from the glomerular basement membrane”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 105 (3): 967–972. doi:10.1073/pnas.0711515105. PMC 2242706. PMID 18198272.

- Bern M, Sand KM, Nilsen J, Sandlie I, Andersen JT (August 2015). “The role of albumin receptors in regulation of albumin homeostasis: Implications for drug delivery”. Journal of Controlled Release. 211: 144–162. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.06.006. PMID 26055641. S2CID 205878058.

- Sand KM, Bern M, Nilsen J, Noordzij HT, Sandlie I, Andersen JT (2015-01-26). “Unraveling the Interaction between FcRn and Albumin: Opportunities for Design of Albumin-Based Therapeutics”. Frontiers in Immunology. 5: 682. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2014.00682. PMC 4306297. PMID 25674083.

- Pyzik M, Rath T, Kuo TT, Win S, Baker K, Hubbard JJ, et al. (April 2017). “Hepatic FcRn regulates albumin homeostasis and susceptibility to liver injury”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 114 (14): E2862–E2871. doi:10.1073/pnas.1618291114. PMC 5389309. PMID 28330995.

- Gupta S, Gach JS, Becerra JC, Phan TB, Pudney J, Moldoveanu Z, et al. (2013-11-01). “The Neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn) enhances human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) transcytosis across epithelial cells”. PLOS Pathogens. 9 (11): e1003776. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1003776. PMC 3836734. PMID 24278022.

- Ward ES, Ober RJ (October 2018). “Targeting FcRn to Generate Antibody-Based Therapeutics”. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 39 (10): 892–904. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2018.07.007. PMC 6169532. PMID 30143244.

- “Ultomiris® (ravulizumab-cwvz) | Alexion”. Retrieved 2021-10-03.

- Dall’Acqua WF, Woods RM, Ward ES, Palaszynski SR, Patel NK, Brewah YA, et al. (November 2002). “Increasing the affinity of a human IgG1 for the neonatal Fc receptor: biological consequences”. Journal of Immunology. 169 (9): 5171–5180. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.169.9.5171. PMID 12391234. S2CID 29398244.

- “Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: FDA Authorizes New Long-Acting Monoclonal Antibodies for Pre-exposure Prevention of COVID-19 in Certain Individuals”. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 8 December 2021.

- Andersen JT, Dalhus B, Viuff D, Ravn BT, Gunnarsen KS, Plumridge A, et al. (May 2014). “Extending serum half-life of albumin by engineering neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn) binding”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 289 (19): 13492–13502. doi:10.1074/jbc.M114.549832. PMC 4036356. PMID 24652290.

- Lee TY, Tjin Tham Sjin RM, Movahedi S, Ahmed B, Pravda EA, Lo KM, et al. (March 2008). “Linking antibody Fc domain to endostatin significantly improves endostatin half-life and efficacy”. Clinical Cancer Research. 14 (5): 1487–1493. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1530. PMID 18316573.

- Poznansky MJ, Halford J, Taylor D (October 1988). “Growth hormone-albumin conjugates. Reduced renal toxicity and altered plasma clearance”. FEBS Letters. 239 (1): 18–22. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(88)80537-4. PMID 3181423. S2CID 38592689.

- Strohl WR (August 2015). “Fusion Proteins for Half-Life Extension of Biologics as a Strategy to Make Biobetters”. BioDrugs. 29 (4): 215–239. doi:10.1007/s40259-015-0133-6. PMC 4562006. PMID 26177629.

- Goldenberg MM (January 1999). “Etanercept, a novel drug for the treatment of patients with severe, active rheumatoid arthritis”. Clinical Therapeutics. 21 (1): 75–87, discussion 1–2. doi:10.1016/S0149-2918(00)88269-7. PMID 10090426.

- Akilesh S, Petkova S, Sproule TJ, Shaffer DJ, Christianson GJ, Roopenian D (May 2004). “The MHC class I-like Fc receptor promotes humorally mediated autoimmune disease”. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 113 (9): 1328–1333. doi:10.1172/JCI18838. PMC 398424. PMID 15124024.

- Hansen RJ, Balthasar JP (June 2003). “Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic modeling of the effects of intravenous immunoglobulin on the disposition of antiplatelet antibodies in a rat model of immune thrombocytopenia”. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 92 (6): 1206–1215. doi:10.1002/jps.10364. PMID 12761810.

- Patel DA, Puig-Canto A, Challa DK, Perez Montoyo H, Ober RJ, Ward ES (July 2011). “Neonatal Fc receptor blockade by Fc engineering ameliorates arthritis in a murine model”. Journal of Immunology. 187 (2): 1015–1022. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1003780. PMC 3157913. PMID 21690327.

- Sockolosky JT, Szoka FC (August 2015). “The neonatal Fc receptor, FcRn, as a target for drug delivery and therapy”. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. Editor’s Collection 2015. 91: 109–124. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2015.02.005. PMC 4544678. PMID 25703189.

- Nimmerjahn F, Ravetch JV (2008-01-01). “Anti-inflammatory actions of intravenous immunoglobulin”. Annual Review of Immunology. 26 (1): 513–533. doi:10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090232. PMID 18370923.

- Vaccaro C, Zhou J, Ober RJ, Ward ES (October 2005). “Engineering the Fc region of immunoglobulin G to modulate in vivo antibody levels”. Nature Biotechnology. 23 (10): 1283–1288. doi:10.1038/nbt1143. PMID 16186811. S2CID 13526188.

- Ulrichts P, Guglietta A, Dreier T, van Bragt T, Hanssens V, Hofman E, et al. (October 2018). “Neonatal Fc receptor antagonist efgartigimod safely and sustainably reduces IgGs in humans”. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 128 (10): 4372–4386. doi:10.1172/JCI97911. PMC 6159959. PMID 30040076.

- Nixon AE, Chen J, Sexton DJ, Muruganandam A, Bitonti AJ, Dumont J, et al. (2015). “Fully human monoclonal antibody inhibitors of the neonatal fc receptor reduce circulating IgG in non-human primates”. Frontiers in Immunology. 6: 176. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2015.00176. PMC 4407741. PMID 25954273.

- Kiessling P, Lledo-Garcia R, Watanabe S, Langdon G, Tran D, Bari M, et al. (November 2017). “The FcRn inhibitor rozanolixizumab reduces human serum IgG concentration: A randomized phase 1 study”. Science Translational Medicine. 9 (414): eaan1208. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aan1208. PMID 29093180. S2CID 206694327.

- Blumberg LJ, Humphries JE, Jones SD, Pearce LB, Holgate R, Hearn A, et al. (December 2019). “Blocking FcRn in humans reduces circulating IgG levels and inhibits IgG immune complex-mediated immune responses”. Science Advances. 5 (12): eaax9586. Bibcode:2019SciA….5.9586B. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aax9586. PMC 6920022. PMID 31897428.

- Newland AC, Sánchez-González B, Rejtő L, Egyed M, Romanyuk N, Godar M, et al. (February 2020). “Phase 2 study of efgartigimod, a novel FcRn antagonist, in adult patients with primary immune thrombocytopenia”. American Journal of Hematology. 95 (2): 178–187. doi:10.1002/ajh.25680. PMC 7004056. PMID 31821591.

- Robak T, Kaźmierczak M, Jarque I, Musteata V, Treliński J, Cooper N, et al. (September 2020). “Phase 2 multiple-dose study of an FcRn inhibitor, rozanolixizumab, in patients with primary immune thrombocytopenia”. Blood Advances. 4 (17): 4136–4146. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2020002003. PMC 7479959. PMID 32886753.

- Werth VP, Culton DA, Concha JS, Graydon JS, Blumberg LJ, Okawa J, et al. (December 2021). “Safety, Tolerability, and Activity of ALXN1830 Targeting the Neonatal Fc Receptor in Chronic Pemphigus”. The Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 141 (12): 2858–2865.e4. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2021.04.031. PMID 34126109. S2CID 235439165.

- Goebeler M, Bata-Csörgő Z, De Simone C, Didona B, Remenyik E, Reznichenko N, et al. (October 2021). “Treatment of pemphigus vulgaris and foliaceus with efgartigimod, a neonatal Fc receptor inhibitor: a phase II multicentre, open-label feasibility trial”. The British Journal of Dermatology. 186 (3): 429–439. doi:10.1111/bjd.20782. hdl:2437/328911. PMID 34608631. S2CID 238355823.

- “argenx Announces U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Approval of VYVGART™ (efgartigimod alfa-fcab) in Generalized Myasthenia Gravis”. Argenx. 17 December 2021.

Further reading

- Dürrbaum-Landmann I, Kaltenhäuser E, Flad HD, Ernst M (April 1994). “HIV-1 envelope protein gp120 affects phenotype and function of monocytes in vitro”. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 55 (4): 545–551. doi:10.1002/jlb.55.4.545. PMID 8145026. S2CID 44412688.

- Leach JL, Sedmak DD, Osborne JM, Rahill B, Lairmore MD, Anderson CL (October 1996). “Isolation from human placenta of the IgG transporter, FcRn, and localization to the syncytiotrophoblast: implications for maternal-fetal antibody transport”. Journal of Immunology. 157 (8): 3317–3322. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.157.8.3317. PMID 8871627. S2CID 10701519.

- Kivelä J, Parkkila S, Waheed A, Parkkila AK, Sly WS, Rajaniemi H (December 1997). “Secretory carbonic anhydrase isoenzyme (CA VI) in human serum”. Clinical Chemistry. 43 (12): 2318–2322. doi:10.1093/clinchem/43.12.2318. PMID 9439449.

- Vaughn DE, Bjorkman PJ (January 1998). “Structural basis of pH-dependent antibody binding by the neonatal Fc receptor”. Structure. 6 (1): 63–73. doi:10.1016/S0969-2126(98)00008-2. PMID 9493268.

- West AP, Bjorkman PJ (August 2000). “Crystal structure and immunoglobulin G binding properties of the human major histocompatibility complex-related Fc receptor(,)”. Biochemistry. 39 (32): 9698–9708. doi:10.1021/bi000749m. PMID 10933786.

- Mikulska JE, Pablo L, Canel J, Simister NE (August 2000). “Cloning and analysis of the gene encoding the human neonatal Fc receptor”. European Journal of Immunogenetics. 27 (4): 231–240. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2370.2000.00225.x. PMID 10998088.

- Zhu X, Meng G, Dickinson BL, Li X, Mizoguchi E, Miao L, et al. (March 2001). “MHC class I-related neonatal Fc receptor for IgG is functionally expressed in monocytes, intestinal macrophages, and dendritic cells”. Journal of Immunology. 166 (5): 3266–3276. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.166.5.3266. PMC 2827247. PMID 11207281.

- Ober RJ, Radu CG, Ghetie V, Ward ES (December 2001). “Differences in promiscuity for antibody-FcRn interactions across species: implications for therapeutic antibodies”. International Immunology. 13 (12): 1551–1559. doi:10.1093/intimm/13.12.1551. PMID 11717196.

- Praetor A, Hunziker W (June 2002). “beta(2)-Microglobulin is important for cell surface expression and pH-dependent IgG binding of human FcRn”. Journal of Cell Science. 115 (Pt 11): 2389–2397. doi:10.1242/jcs.115.11.2389. PMID 12006623.

- Claypool SM, Dickinson BL, Yoshida M, Lencer WI, Blumberg RS (August 2002). “Functional reconstitution of human FcRn in Madin-Darby canine kidney cells requires co-expressed human beta 2-microglobulin”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (31): 28038–28050. doi:10.1074/jbc.M202367200. PMC 2825174. PMID 12023961.

- Praetor A, Jones RM, Wong WL, Hunziker W (August 2002). “Membrane-anchored human FcRn can oligomerize in the absence of IgG”. Journal of Molecular Biology. 321 (2): 277–284. doi:10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00626-5. PMID 12144784.

- Shah U, Dickinson BL, Blumberg RS, Simister NE, Lencer WI, Walker WA (February 2003). “Distribution of the IgG Fc receptor, FcRn, in the human fetal intestine”. Pediatric Research. 53 (2): 295–301. doi:10.1203/01.pdr.0000047663.81816.e3. PMC 2819091. PMID 12538789.

- Chaudhury C, Mehnaz S, Robinson JM, Hayton WL, Pearl DK, Roopenian DC, Anderson CL (February 2003). “The major histocompatibility complex-related Fc receptor for IgG (FcRn) binds albumin and prolongs its lifespan”. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 197 (3): 315–322. doi:10.1084/jem.20021829. PMC 2193842. PMID 12566415.

- Schilling R, Ijaz S, Davidoff M, Lee JY, Locarnini S, Williams R, Naoumov NV (August 2003). “Endocytosis of hepatitis B immune globulin into hepatocytes inhibits the secretion of hepatitis B virus surface antigen and virions”. Journal of Virology. 77 (16): 8882–8892. doi:10.1128/JVI.77.16.8882-8892.2003. PMC 167249. PMID 12885906.

- Zhou J, Johnson JE, Ghetie V, Ober RJ, Ward ES (September 2003). “Generation of mutated variants of the human form of the MHC class I-related receptor, FcRn, with increased affinity for mouse immunoglobulin G”. Journal of Molecular Biology. 332 (4): 901–913. doi:10.1016/S0022-2836(03)00952-5. PMID 12972260.

- Cianga P, Cianga C, Cozma L, Ward ES, Carasevici E (December 2003). “The MHC class I related Fc receptor, FcRn, is expressed in the epithelial cells of the human mammary gland”. Human Immunology. 64 (12): 1152–1159. doi:10.1016/j.humimm.2003.08.025. PMID 14630397.

- Ober RJ, Martinez C, Vaccaro C, Zhou J, Ward ES (February 2004). “Visualizing the site and dynamics of IgG salvage by the MHC class I-related receptor, FcRn”. Journal of Immunology. 172 (4): 2021–2029. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.172.4.2021. PMID 14764666.

External links

- neonatal+Fc+receptor at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

Leave a Reply