Lady Mary Wortley Montagu introduced smallpox variolation – which she called engrafting – to Britain in 1717

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (1689 – 1762) was an English aristocrat, medical pioneer, writer, and poet. Born in 1689, Lady Mary spent her early life in England. In 1712, Lady Mary married Edward Wortley Montagu, who later served as the British ambassador to the Sublime Porte. Lady Mary joined her husband on the Ottoman excursion, where she was to spend the next two years of her life. During her time there, Lady Mary wrote extensively on her experience as a woman in Ottoman Constantinople. After her return to England, Lady Mary devoted her attention to the upbringing of her family before dying of cancer in 1762.

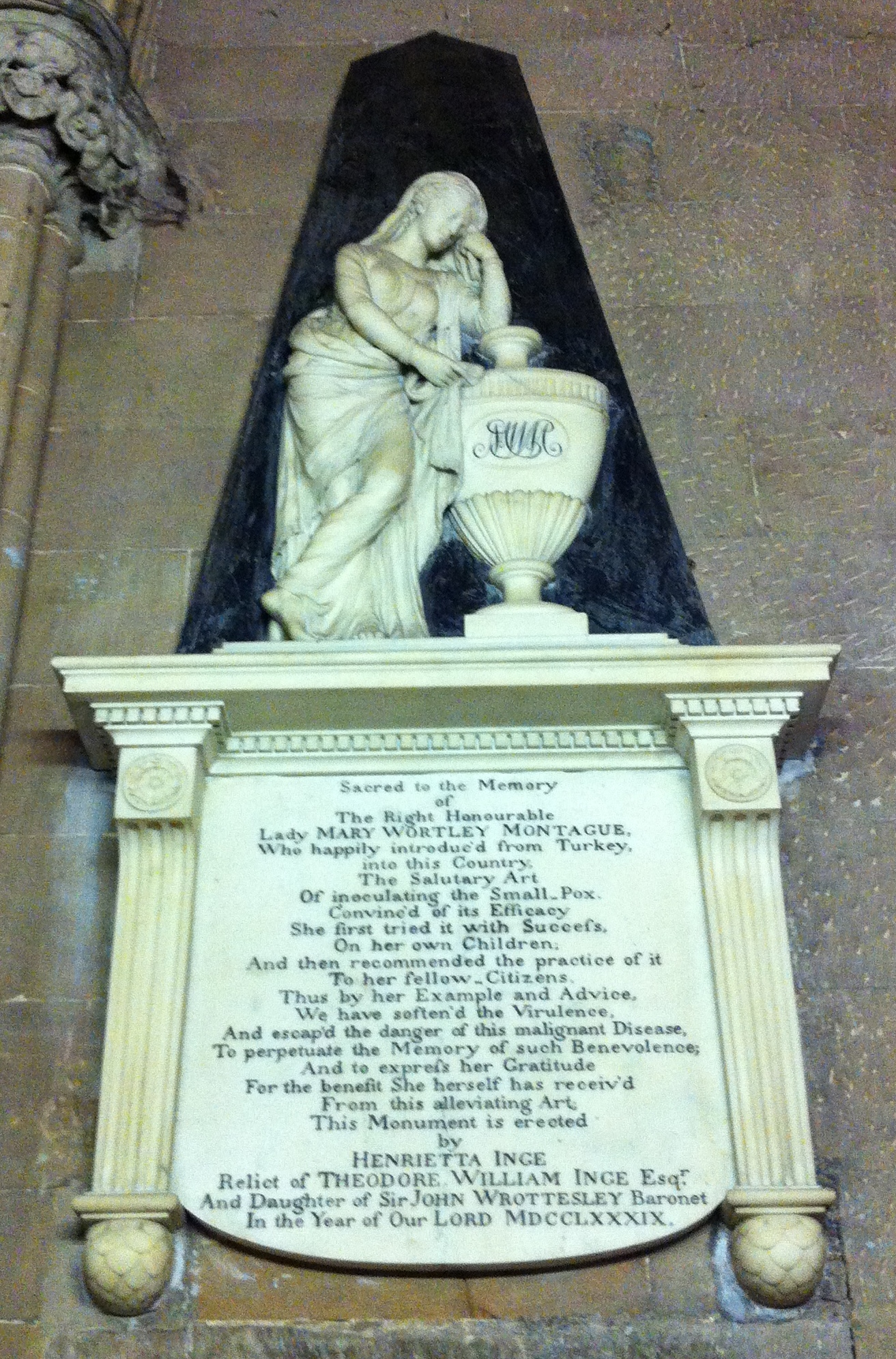

Although having regularly socialised with the court of George I and George Augustus, Prince of Wales (later King George II) , Lady Mary is today chiefly remembered for her letters, particularly her Turkish Embassy Letters describing her travels to the Ottoman Empire, as wife to the British ambassador to Turkey, which Billie Melman describes as “the very first example of a secular work by a woman about the Muslim Orient”. Aside from her writing, Mary is also known for introducing and advocating smallpox inoculation in Britain after her return from Turkey.

- Grundy, Isobel. “Montagu, Lady Mary Wortley”. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/19029.

- Melman, Billie. Women’s Orients: English Women and the Middle East, 1718–1918. University of Michigan Press. 1992. Print.

- Ferguson, Donna (28 March 2021). “How Mary Wortley Montagu’s bold experiment led to smallpox vaccine – 75 years before Jenner”. The Guardian. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

Ottoman smallpox inoculation

Smallpox inoculation

In the 18th century, Europeans began an experiment known as inoculation or variolation to prevent, not cure the smallpox. Lady Mary Wortley Montagu defied convention, most memorably by promoting smallpox inoculation to Western medicine after witnessing it during her travels and stay in the Ottoman Empire. Previously, Lady Mary’s brother had died of smallpox in 1713, and although Lady Mary recovered from the disease in 1715, it left her with a disfigured face. In the Ottoman Empire, she visited the women in their segregated zenanas, a house for Muslims and Hindus, making friends and learning about Turkish customs. There in March 1717, she witnessed the practice of inoculation against smallpox – variolation – which she called engrafting, and wrote home about it in a number of her letters. The most famous of these letters was her “Letter to a Friend” of 1 April 1717.

- Ferguson, Donna (28 March 2021). “How Mary Wortley Montagu’s bold experiment led to smallpox vaccine – 75 years before Jenner”. The Guardian. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- Lindemann, Mary (2013). Medicine and Society in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge University Press. p. 74. ISBN 978-0521732567.

- Lady Mary Wortley Montagu: Selected Letters. Ed. Isobel Grundy. Penguin Books, 1997. Print.

- Rosenhek, Jackie. “Safe Smallpox Inoculations”, Doctor’s Review: Medicine on the Move, February 2005. Web. 10 November 2015. Safe Smallpox Inoculations Archived 4 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine.

- Lewis, Melville; Montagu, Mary Wortley (1925). Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, Her Life and Letters (1689–1762). Hutchinson. p. 135. ISBN 978-1419129087.

Variolation used live smallpox virus in the pus taken from a mild smallpox blister and introduced it into scratched skin of the arm or leg (the most usual spots) of a previously uninfected person to promote immunity to the disease. Consequently, the inoculate would develop a milder case of smallpox than the one he/she might have contracted.

- Lindemann, Mary (2013). Medicine and Society in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge University Press. p. 74. ISBN 978-0521732567.

- Rosenhek, Jackie, “Safe Smallpox Inoculations”. Doctor’s Review: Medicine on the Move, February 2005. Web. 10 November 2015. Safe Smallpox Inoculations Archived 4 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine

Lady Mary was eager to spare her children, thus, in March 1718 she had her nearly five-year-old son, Edward, inoculated there with the help of Embassy surgeon Charles Maitland. In fact, her son was the “first English person to undergo the operation.” In a letter to a friend in England, Montagu wrote, “There is a set of old women [here], who make it their business to perform the operation, every autumn…when then great heat is abated…thousands undergo this operation…[and there] is not one example of anyone that has died in it.” Afterwards, she updated the status of Edward to her husband: “The Boy was engrafted last Tuesday, and is at this time singing and playing, and very impatient for his supper. I pray God my next may give as good an account of him.” On her return to London, she enthusiastically promoted the procedure, but encountered a great deal of resistance from the medical establishment, because it was a folk treatment process.

- Ferguson, Donna (28 March 2021). “How Mary Wortley Montagu’s bold experiment led to smallpox vaccine – 75 years before Jenner”. The Guardian. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- Grundy, Isobel. “Montagu, Lady Mary Wortley”. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/19029.

- Lindemann, Mary (2013). Medicine and Society in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge University Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-0521732567.

- Halsband, Robert; Montagu, Mary Wortley (1965). The Complete Letters of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, 1708–1720. Oxford University Press. p. 392. ISBN 978-0198114468.

- Lady Mary Wortley Montagu: Selected Letters. Ed. Isobel Grundy. Penguin Books, 1997. Print.

- Rosenhek, Jackie. “Safe Smallpox Inoculations”, Doctor’s Review: Medicine on the Move, February 2005. Web. 10 November 2015. Safe Smallpox Inoculations Archived 4 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine.

- Lewis, Melville; Montagu, Mary Wortley (1925). Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, Her Life and Letters (1689–1762). Hutchinson. p. 135. ISBN 978-1419129087.

In April 1721, when a smallpox epidemic struck England, she had her daughter inoculated by Maitland, the same physician who had inoculated her son at the Embassy in Turkey, and publicised the event. This was the first such operation done in England. She persuaded Caroline of Ansbach, the Princess of Wales, to test the treatment. In August 1721, seven prisoners at Newgate Prison awaiting execution were offered the chance to undergo variolation instead of execution: they all survived and were released. Despite this, controversy over smallpox inoculation intensified. However Caroline, Princess of Wales, was convinced of its value. The Princess’s two daughters Amelia and Caroline were successfully inoculated in April 1722 by French-born surgeon Claudius Amyand. In response to the general fear of inoculation, Lady Mary, under a pseudonym, wrote and published an article describing and advocating in favour of inoculation in September 1722. Later, other royal families soon followed Montagu’s act. For instance, in 1768, Catherine the Great of Russia had herself and her son, the future Tsar Paul, inoculated. The Russians continued to refine the process.

- Lindemann, Mary (2013). Medicine and Society in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge University Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-0521732567.

- Lady Mary Wortley Montagu: Selected Letters. Ed. Isobel Grundy. Penguin Books, 1997. Print.

- Grundy, Isobel. “Montagu, Lady Mary Wortley”. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/19029.

Nevertheless, inoculation was not always a safe process; inoculates developed a real case of smallpox and could infect others. The inoculation resulted in a “small number of deaths and complications, including serious infections.”

- Ferguson, Donna (28 March 2021). “How Mary Wortley Montagu’s bold experiment led to smallpox vaccine – 75 years before Jenner”. The Guardian. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- Lindemann, Mary (2013). Medicine and Society in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge University Press. p. 75-77. ISBN 978-0521732567.

- Halsband, Robert; Montagu, Mary Wortley (1965). The Complete Letters of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, 1708–1720. Oxford University Press. p. 392. ISBN 978-0198114468.

Subsequently, Edward Jenner, who was 13 years old when Lady Mary died in 1762, developed the much safer technique of vaccination using cowpox instead of smallpox. Jenner’s method involves “engrafting lymph taken from a pustulate of cowpox on the hand of a milkmaid into the arm of an inoculate.” Jenner first tested his method on James Phipps, an eight-year-old boy, and when Phipps did not have any reaction after the procedure, Jenner claimed that his procedure “bestowed immunity against smallpox.” Then, after spending the next few years experimenting his new procedure, he discovered that his hypothesis was correct. As vaccination gained acceptance, variolation gradually fell out of favour. In the 20th century, a concerted campaign by the WHO to eradicate smallpox via vaccination would succeed by 1979. Lady Mary Wortley Montagu’s introduction of smallpox inoculation had ultimately led to the development of vaccines, and the later eradication of smallpox.[citation needed]

- Lindemann, Mary (2013). Medicine and Society in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge University Press. p. 77. ISBN 978-0521732567.

- Lindemann, Mary (2013). Medicine and Society in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge University Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-0521732567.

Leave a Reply