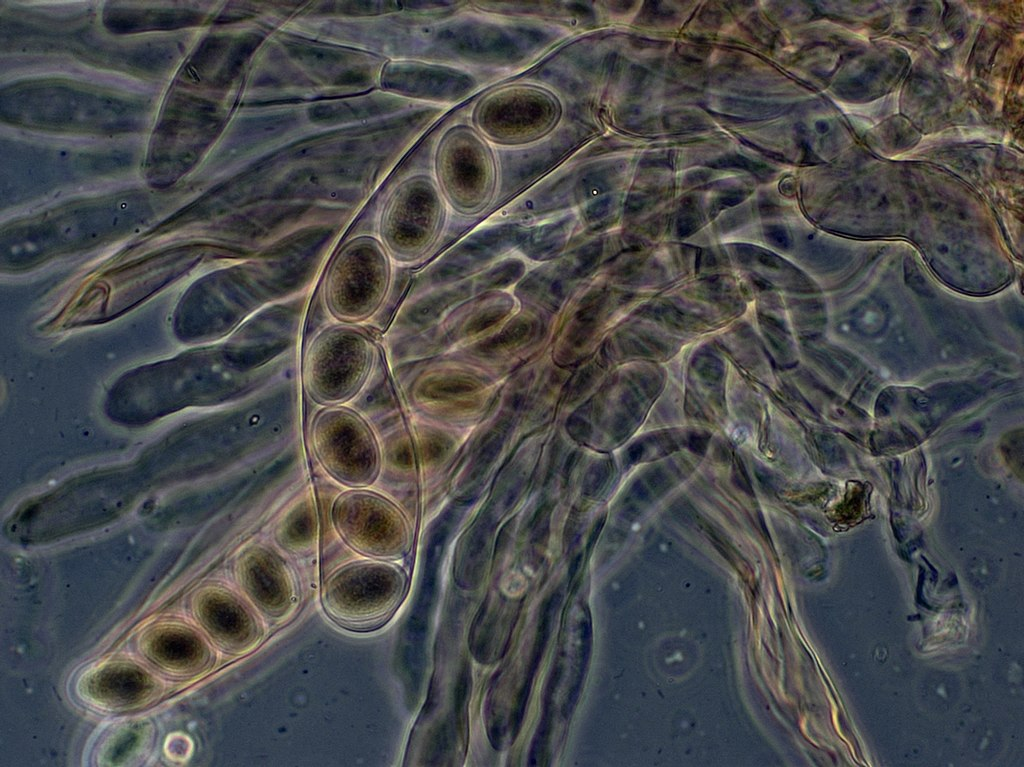

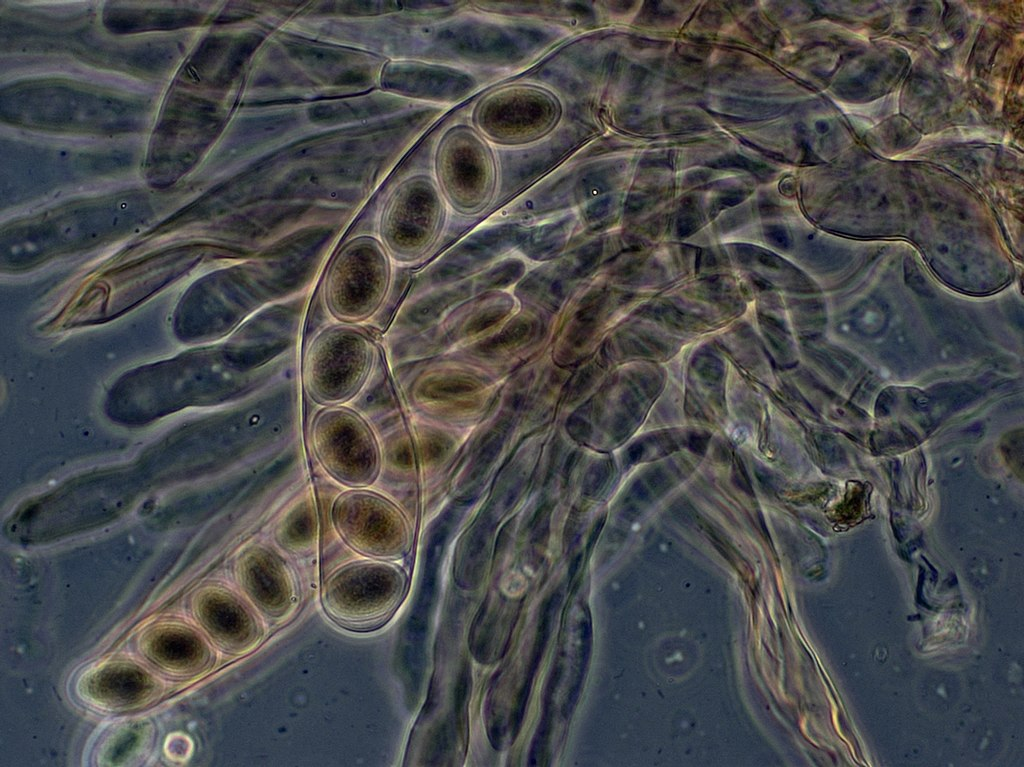

ASCUS (Formerly Theca)

This article is about the spore-bearing cell in fungi. For Atypical Squamous Cells of Undetermined Significance (ASCUS), see Bethesda system. For the Greek mythological giant, see Ascus (mythology).

(pl. asci) a cell present in the fruiting body of ASCOMYCETE fungi in which the fusion of HAPLOID nuclei occurs during sexual reproduction. This is normally followed by MEIOSIS, giving rise to four haploid cells, after which MITOSIS produces eight ASCOSPORES. The precise arrangement of ascospores within the ascus enables the events at meiosis to be fully analysed (see TETRAD ANALYSIS). The asci are usually enclosed within an aggregation of hyphae termed an ASCOCARP, a number of different types being recognized, e.g. perithecium, cleistothecium, apothecium. (Collins Dictionary of Biology, 3rd ed. © W. G. Hale, V. A. Saunders, J. P. Margham 2005)

An ascus (from Ancient Greek ἀσκός (askós) ‘skin bag, wineskin’; pl.: asci)[1] is the sexual spore-bearing cell produced in ascomycete fungi. Each ascus usually contains eight ascospores (or octad), produced by meiosis followed, in most species, by a mitotic cell division. However, asci in some genera or species can occur in numbers of one (e.g. Monosporascus cannonballus), two, four, or multiples of four. In a few cases, the ascospores can bud off conidia that may fill the asci (e.g. Tympanis) with hundreds of conidia, or the ascospores may fragment, e.g. some Cordyceps, also filling the asci with smaller cells. Ascospores are nonmotile, usually single celled, but not infrequently may be coenocytic (lacking a septum), and in some cases coenocytic in multiple planes. Mitotic divisions within the developing spores populate each resulting cell in septate ascospores with nuclei. The term ocular chamber, or oculus, refers to the epiplasm (the portion of cytoplasm not used in ascospore formation) that is surrounded by the “bourrelet” (the thickened tissue near the top of the ascus).[2]

Typically, a single ascus will contain eight ascospores (or octad). The eight spores are produced by meiosis followed by a mitotic division. Two meiotic divisions turn the original diploid zygote nucleus into four haploid ones. That is, the single original diploid cell from which the whole process begins contains two complete sets of chromosomes. In preparation for meiosis, all the DNA of both sets is duplicated, to make a total of four sets. The nucleus that contains the four sets divides twice, separating into four new nuclei – each of which has one complete set of chromosomes. Following this process, each of the four new nuclei duplicates its DNA and undergoes a division by mitosis. As a result, the ascus will contain four pairs of spores. Then the ascospores are released from the ascus.

In many cases the asci are formed in a regular layer, the hymenium, in a fruiting body which is visible to the naked eye, here called an ascocarp or ascoma. In other cases, such as single-celled yeasts, no such structures are found. In rare cases asci of some genera can regularly develop inside older discharged asci one after another, e.g. Dipodascus.

Asci normally release their spores by bursting at the tip, but they may also digest themselves, passively releasing the ascospores either in a liquid or as a dry powder. Discharging asci usually have a specially differentiated tip, either a pore or an operculum. In some hymenium forming genera, when one ascus bursts, it can trigger the bursting of many other asci in the ascocarp resulting in a massive discharge visible as a cloud of spores – the phenomenon called “puffing”. This is an example of positive feedback. A faint hissing sound can also be heard for species of Peziza and other cup fungi.

Asci, notably those of Neurospora crassa, have been used in laboratories for studying the process of meiosis, because the four cells produced by meiosis line up in regular order. By modifying genes coding for spore color and nutritional requirements, the biologist can study crossing over and other phenomena. The formation of asci and their use in genetic analysis are described in detail in Neurospora crassa.

Asci of most Pezizomycotina develop after the formation of croziers at their base. The croziers help maintain a brief dikaryon. The compatible nuclei of the dikaryon merge forming a diploid nucleus that then undergoes meiosis and ultimately internal ascospore formation. Members of the Taphrinomycotina and Saccharomycotina do not form croziers.

Classification

The form of the ascus, the capsule which contains the sexual spores, is important for classification of the Ascomycota. There are four basic types of ascus.

- A unitunicate-operculate ascus has a “lid”, the Operculum, which breaks open when the spores are mature and allows the spores to escape. Unitunicate-operculate asci only occur in those ascocarps which have apothecia, for instance the morels. ‘Unitunicate’ means ‘single-walled’.

- Instead of an operculum, a unitunicate-inoperculate ascus has an elastic ring that functions like a pressure valve. Once mature the elastic ring briefly expands and lets the spores shoot out. This type appears both in apothecia and in perithecia; an example is the illustrated Hypomyces chrysospermus.

- A bitunicate ascus is enclosed in a double wall. This consists of a thin, brittle outer shell and a thick elastic inner wall. When the spores are mature, the shell splits open so that the inner wall can take up water. As a consequence, this begins to extend with its spores until it protrudes above the rest of the ascocarp so that the spores can escape into free air without being obstructed by the bulk of the fruiting body. Bitunicate asci occur only in pseudothecia and are found only in the classes Dothideomycetes and Chaetothyriomycetes (which were formerly united in the old class Loculoascomycetes). Examples: Venturia inaequalis (apple scab) and Guignardia aesculi (Brown Leaf Mold of Horse Chestnut).

- Prototunicate asci are mostly spherical in shape and have no mechanism for forcible dispersal. The mature ascus wall dissolves allowing the spores to escape, or it is broken open by other influences, such as animals. Asci of this type can be found both in perithecia and in cleistothecia, for instance with Dutch elm disease (Ophiostoma). This is something of a catch-all term for cases which do not fit into the other three ascus types, and they probably belong to several independent groups which evolved separately from unitunicate asci.

Ascospores

An ascospore is a spore contained in an ascus, or that was produced inside an ascus. This kind of spore is specific to fungi classified as ascomycetes (Ascomycota).

The ascospores of Blumeria graminis are formed and released under the humid conditions.[3] After landing onto a suitable surface, unlike conidia, ascospores of Blumeria graminis showed a more variable developmental patterns.[3]

The fungi Saccharomyces produces ascospores when grown on V-8 medium, acetate ascospore agar, or Gorodkowa medium. These ascospores are globose and located in asci. Each ascus contains one to four ascospores. The asci do not rupture at maturity. Ascospores are stained with Kinyoun stain and ascospore stain. When stained with Gram stain, ascospores are gram-negative while vegetative cells are gram-positive.

The fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe is a single-celled haploid organism that reproduces asexually by mitosis and fission. However, exposure to the DNA damaging agent hydrogen peroxide induces pair-wise mating of haploid cells of opposite mating type to form transient diploid cells that then undergo meiosis to form asci, each with four ascospores.[4] The production of viable ascospores depends on successful recombinational repair during meiosis.[5] When this repair is defective a quality control mechanism prevents germination of damaged ascospores. These findings suggest that mating followed by meiosis is an adaptation for repairing DNA damage in the parental haploid cells in order to allow production of viable progeny ascospores.

References

- Henry Liddell; Robert Scott. “ἀσκός”. A Greek-English Lexicon. Retrieved 27 February 2018 – via Perseus Project.

- Hawksworth DL. (2013). Ascomycete Systematics: Problems and Perspectives in the Nineties. Springer. p. 116. ISBN 978-1-4757-9290-4.

- Zhu, Mo; Riederer, Markus; Hildebrandt, Ulrich (2017). “Very-long-chain aldehydes induce appressorium formation in ascospores of the wheat powdery mildew fungus Blumeria graminis”. Fungal Biology. 121 (8): 716–728. doi:10.1016/j.funbio.2017.05.003. PMID 28705398.

- Bernstein C, Johns V (April 1989). “Sexual reproduction as a response to H2O2 damage in Schizosaccharomyces pombe”. J. Bacteriol. 171 (4): 1893–7. doi:10.1128/jb.171.4.1893-1897.1989. PMC 209837. PMID 2703462.

- Guo H, King MC (2013). “A quality control mechanism linking meiotic success to release of ascospores”. PLOS ONE. 8 (12): e82758. Bibcode:2013PLoSO…882758G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0082758. PMC 3846778. PMID 24312672.

Leave a Reply