The Institut für Sexualwissenschaft was an early private sexology research institute in Germany from 1919 to 1933. The name is variously translated as Institute of Sex Research, Institute of Sexology, Institute for Sexology or Institute for the Science of Sexuality. The Institute was a non-profit foundation situated in Tiergarten, Berlin. It was the first sexology research center in the world.

- Wolff 1986, p. 180.

- O’Brien, Jodi (2009). Encyclopedia of Gender and Society. SAGE Publications. p. 425. ISBN 978-1-4129-0916-7.

- Beachy 2014, p. 160–161.

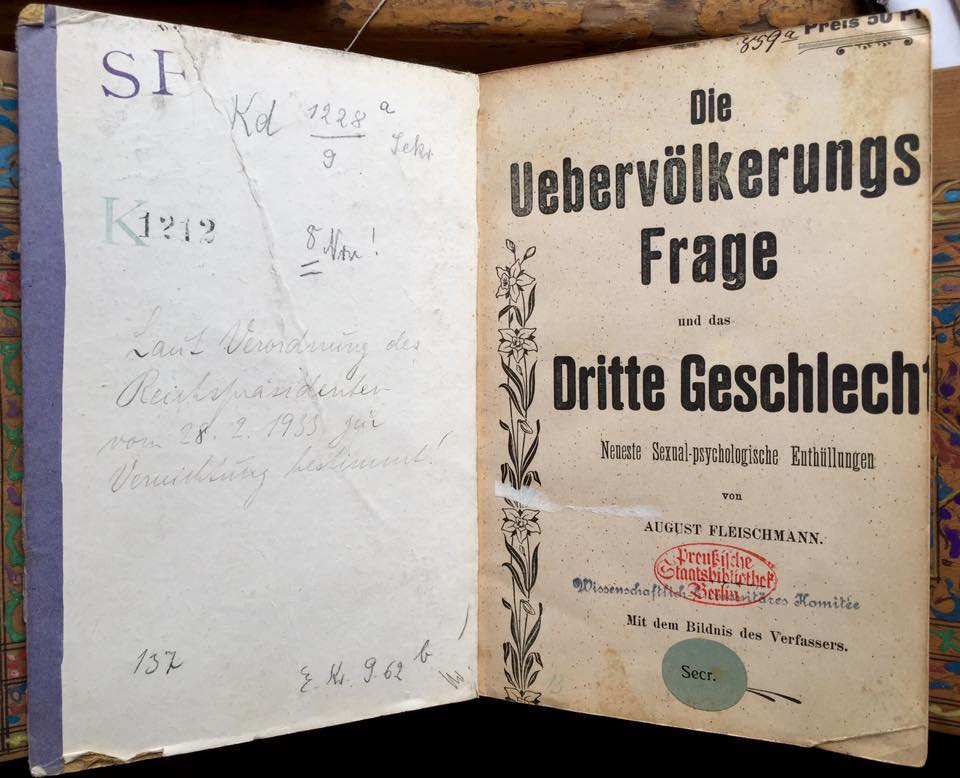

The Institute was headed by Magnus Hirschfeld, who since 1897 had run the Wissenschaftlich-humanitäres Komitee (‘Scientific-Humanitarian Committee’), which campaigned on progressive and rational grounds for LGBT rights and tolerance. The Committee published the long-running journal Jahrbuch für sexuelle Zwischenstufen. Hirschfeld built a unique library at the institute on gender, same-sex love and eroticism.

- Oosterhuis, Harry, ed. (1991). Homosexuality and Male Bonding in Pre-Nazi Germany. Translated by Hubert C. Kennedy. Harrington Park Press. ISBN 978-1-56023-008-3. Archived from the original on July 21, 2009.

- Strochlic, Nina (28 June 2022). “The great hunt for the world’s first LGBTQ archive”. National Geographic. Archived from the original on 5 July 2022. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

The institute pioneered research and treatment for various matters regarding gender and sexuality, including gay, transgender, and intersex topics. In addition, it offered various other services to the general public: this included treatment for alcoholism, gynecological examinations, marital and sex counseling, treatment for venereal diseases, and access to contraceptive treatment. It offered education on many of these matters to both health professionals and laypersons.

- Beachy 2014, p. 160–164.

- Wolff 1986, p. 181.

The Nazi book burnings in Berlin included the archives of the institute. After the Nazis gained control of Germany in the 1930s, the institute and its libraries were destroyed as part of a Nazi government censorship program by youth brigades, who burned its books and documents in the street.

- “Institute of Sexology”. Qualia Folk. 8 December 2011. Archived from the original on 18 January 2015. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- “Magnus Hirschfeld”. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

The bronze bust of Hirschfeld survived. A street cleaner salvaged and stored it the day after the burnings, and it was donated to the Berlin Academy of Arts after World War II. Reportedly also spared from the destruction were a large collection of psycho-biological questionnaires, pertaining to Hirschfeld’s research of homosexuality. The Nazis were assured that these were simple medical histories. However, few of these have since been rediscovered.

- Strochlic, Nina (28 June 2022). “The great hunt for the world’s first LGBTQ archive”. National Geographic. Archived from the original on 5 July 2022. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

- Bauer, Heike (2014). “Burning Sexual Subjects: Books, Homophobia and the Nazi Destruction of the Institute of Sexual Science in Berlin”. In Partington, Gill; Smyth, Adam (eds.). Book Destruction from the Medieval to the Contemporary. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 17–33. doi:10.1057/9781137367662_2. ISBN 978-1-137-36766-2. Retrieved 2022-10-07.

Origins and purpose

The Institute of Sex Research was founded by Magnus Hirschfeld and his collaborators Arthur Kronfeld, a once famous psychotherapist and later professor at the Charité, and Friedrich Wertheim, a dermatologist. Hirschfeld gave a speech on 1 July 1919, when the institute was inaugurated. It opened on 6 July 1919. The building, located in the Tiergarten district, was purchased by Hirschfeld from the government of the Free State of Prussia following World War I. A neighboring building was purchased in 1921, adding more overall space to the institute.

- Tamagne, Florence (2007). “Liberation on the Move: The Golden Age of Homosexual Movements”. A History of Homosexuality in Europe, Vol. I & II: Berlin, London, Paris 1919-1939. Algora Publishing. pp. 59–104. ISBN 978-0-87586-357-3.

- “Arthur Kronfeld”. Internet Publikation für Allgemeine und Integrative Psychotherapie. Archived from the original on 8 August 2022. Retrieved 2022-01-23.

- Giami, Alain; Levinson, Sharman (2021-07-12). Histories of Sexology: Between Science and Politics. Springer Nature. p. 55. ISBN 978-3-030-65813-7.

- “Magnus Hirschfeld and HKW”. Haus der Kulturen der Welt. Archived from the original on 9 November 2021. Retrieved October 7, 2022.

- Jander, Thomas (23 July 2019). “What’s that for? A Licence to Be (Different)”. Deutsches Historisches Museum Blog. Archived from the original on 21 November 2021. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- Grossmann, Atina (1995). Reforming Sex: The German Movement for Birth Control and Abortion Reform, 1920-1950. Oxford University Press. pp. 15–17. ISBN 978-0-19-505672-3.

- Bauer, Heike (2014). “Burning Sexual Subjects: Books, Homophobia and the Nazi Destruction of the Institute of Sexual Science in Berlin”. In Partington, Gill; Smyth, Adam (eds.). Book Destruction from the Medieval to the Contemporary. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 17–33. doi:10.1057/9781137367662_2. ISBN 978-1-137-36766-2. Retrieved 2022-10-07.

- Beachy 2014, p. 161.

- Wolff 1986, p. 182.

As well as being a research library and housing a large archive, the institute also included medical, psychological, and ethnological divisions, and a marriage and sex counseling office. Other fixtures at the institute included a museum for sexual artifacts, medical exam rooms, and a lecture hall. The institute conducted around 18,000 consultations for 3,500 people in its first year. Clients often received advice for free. Poorer visitors also received medical treatment for free.[citation needed] According to Hirschfeld, about 1,250 lectures had been held in the first year.

- Tamagne, Florence (2007). “Liberation on the Move: The Golden Age of Homosexual Movements”. A History of Homosexuality in Europe, Vol. I & II: Berlin, London, Paris 1919-1939. Algora Publishing. pp. 59–104. ISBN 978-0-87586-357-3.

- Matte, Nicholas (2005-10-01). “International Sexual Reform and Sexology in Europe, 1897–1933”. Canadian Bulletin of Medical History. 22 (2): 253–270. doi:10.3138/cbmh.22.2.253. ISSN 2816-6469. PMID 16482697.

- Beachy 2014, p. ix.

- Marcuse, Max (2011-08-02). Handwörterbuch der Sexualwissenschaft: Enzyklopädie der natur- und kulturwissenschaftlichen Sexualkunde des Menschen [Hand Dictionary of Sexology: Encyclopedia of Natural and Cultural-Scientific Sex Education in Humans] (in German). De Gruyter. pp. xi. ISBN 978-3-11-088786-0.

- Wolff 1986, p. 177.

In addition, the institute advocated sex education, contraception, the treatment of sexually transmitted diseases, and women’s emancipation. Inscribed on the building was the phrase per scientiam ad justitiam (translated as “through science to justice”). This was also the personal motto of Hirschfeld as well as the slogan of the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee.

- “Magnus Hirschfeld”. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- Weeks, Jeffrey (1997). Segal, Lynne (ed.). New Sexual Agendas. New York University Press. pp. 48–49. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-25549-8. ISBN 0-8147-8076-8. OCLC 35646591. OL 19515251W. S2CID 142426128.

- Beachy 2014, p. 86.

Organization

The institute was financed by the Magnus-Hirschfeld-Foundation, a charity which itself was funded by private donations. Along with Magnus Hirschfeld, a number of others (including many professional specialists) worked on the staff of the institute at different points in time, including:

| Felix Abraham [de] — psychiatrist August Bessunger — radiologist Karl Giese — archivist Berndt Götz — psychiatrist Hans Graaz — naturopath, medical doctor Friedrich Hauptstein — administrative director Kurt Hiller — lawyer Max Hodann — sex educator Hans Wilhelm Carl Friedenthal [de] — anthropologist Hans Kreiselmaier — gynecologist Arthur Kronfeld — psychiatrist, psychologist | Ewald Lausch — medical assistant Ludwig Levy-Lenz — gynecologist Eugen Littaur — otolaryngologist Franz Prange — endocrinologist Ferdinand von Reitzenstein [de] — ethnologist Adelheid Rennhack — housekeeper Arthur Röser — librarian Bernard Schapiro — dermatologist, andrologist Arthur Weil — neuroendocrinologist, neuropathologist Friedrich Wertheim — dermatologist |

- Bauer, Heike (2014). “Burning Sexual Subjects: Books, Homophobia and the Nazi Destruction of the Institute of Sexual Science in Berlin”. In Partington, Gill; Smyth, Adam (eds.). Book Destruction from the Medieval to the Contemporary. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 17–33. doi:10.1057/9781137367662_2. ISBN 978-1-137-36766-2. Retrieved 2022-10-07.

- Dose 2014, p. 53–55.

- “Hans Graaz, M.D.” Magnus-Hirschfeld-Gesellschaft. Retrieved December 4, 2022.

- Kraß, Andreas; Sluhovsky, Moshe; Yonay, Yuval (2021-12-31). Queer Jewish Lives Between Central Europe and Mandatory Palestine: Biographies and Geographies. transcript Verlag. pp. 34–36. ISBN 978-3-8394-5332-2.

- Borgwardt, G. (2002). “Bernard Schapiro”. Sudhoffs Archiv. 86 (2): 181–197. PMID 12703271.

Some others worked for the institute in various domestic affairs. Some of the people who worked at the institute simultaneously lived there, including Hirschfeld and Giese. Affiliated groups held offices at the institute. This included the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee, Helene Stöcker‘s Deutscher Bund für Mutterschutz und Sexualreform [de], and the World League for Sexual Reform (WLSR). The WLSR has been described as the “international face” of the institute. In 1929 Hirschfeld presided over the third international congress of the WLSR at Wigmore Hall. During his address there, he stated that “A sexual impulse based on science is the only sound system of ethics.”

- Bauer, Heike (2014). “Burning Sexual Subjects: Books, Homophobia and the Nazi Destruction of the Institute of Sexual Science in Berlin”. In Partington, Gill; Smyth, Adam (eds.). Book Destruction from the Medieval to the Contemporary. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 17–33. doi:10.1057/9781137367662_2. ISBN 978-1-137-36766-2. Retrieved 2022-10-07.

- Matte, Nicholas (2005-10-01). “International Sexual Reform and Sexology in Europe, 1897–1933”. Canadian Bulletin of Medical History. 22 (2): 253–270. doi:10.3138/cbmh.22.2.253. ISSN 2816-6469. PMID 16482697.

- Weeks, Jeffrey (1997). Segal, Lynne (ed.). New Sexual Agendas. New York University Press. pp. 48–49. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-25549-8. ISBN 0-8147-8076-8. OCLC 35646591. OL 19515251W. S2CID 142426128.

- Beachy 2014, p. 163.

- Healey, Dan (2012-04-26). Homosexual Desire in Revolutionary Russia: The Regulation of Sexual and Gender Dissent. University of Chicago Press. pp. 132–138. ISBN 978-0-226-92254-6.

- “League for Sexual Reform: International Congress Opened”. The Times. No. 45303. 9 September 1929. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- “League for Sexual Reform”. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 93 (16): 1234–1235. 19 October 1929. Archived from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

Divisions for the institute included ones dedicated to sexual biology, pathology, sociology and ethnography. Plans were allotted for the institute to both research and practice medicine in equal measure, though by 1925 a lack of funding meant the institute had to cut its medical research. This was to include matters of sexuality, gender, venereal disease, and birth control.

- Beachy 2014, p. 161–162.

Transgender people were on the staff of the institute as receptionists and maids, as well as being among the clients there.

- Crocq, Marc-Antoine (2021-01-01). “How gender dysphoria and incongruence became medical diagnoses – a historical review”. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 23 (1): 44–51. doi:10.1080/19585969.2022.2042166. ISSN 1958-5969. PMC 9286744. PMID 35860172.

- Stryker, Susan (2017-11-07). “A Hundred-Plus Years of Transgender History”. Transgender History: The Roots of Today’s Revolution (2nd ed.). Basic Books. ISBN 978-1-58005-690-8. Archived from the original on 23 December 2021.

Bibliography

- Dose, Ralf (2014). Magnus Hirschfeld: The Origins of the Gay Liberation Movement. New York University Press. ISBN 978-1-58367-439-0. JSTOR j.ctt9qg6t2. OCLC 870272914.

- Beachy, Robert (2014). Gay Berlin: Birthplace of a Modern Identity. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-307-47313-4.

- Wolff, Charlotte (1986). Magnus Hirschfeld: A Portrait of a Pioneer in Sexology. Quartet Books. ISBN 978-0-7043-2569-2. OCLC 16923065. USHMM: bib31255.

Further reading

- Isherwood, Christopher. (1976) Christopher and His Kind, 1929-1939, 1st edition. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Full text on OpenLibrary.

- Blasius, Mark and Phelan, Shane ed. (1997) We Are Everywhere: A Historical Source Book of Gay and Lesbian Politics (See the chapter: “The Emergence of a Gay and Lesbian Political Culture in Germany” by James D. Steakley).

- Grau, Günter ed. (1995) Hidden Holocaust? Gay and Lesbian Persecution in Germany 1933-45.

- Lauritsen, John and Thorstad, David (1995) The Early Homosexual Rights Movement (1864-1935). (Second Edition revised)

- Steakley, James D. (9 June 1983) “Anniversary of a Book Burning”. pp.18–19, 57. The Advocate (Los Angeles)

- Marhoefer, Laurie. (2015) Sex and the Weimar Republic: German Homosexual Emancipation and the Rise of the Nazis. University of Toronto Press.

- Taylor, Michael Thomas; Timm, Annette F.; Herrn, Rainer eds. (2017) Not Straight From Germany: Sexual Publics and Sexual Citizenship Since Magnus Hirschfeld. JSTOR: 10.3998/mpub.9238370.

Film

- Rosa von Praunheim, director (Germany, 2001) The Einstein of Sex (A biographical drama about Magnus Hirschfeld – English subtitled version available).

External links

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Institut für Sexualwissenschaft.

- “Institute for Sexual Science (1919-1933)” Online exhibition of the Magnus Hirschfeld Society – warning, complex JavaScript and pop-up windows.

- Documentation in the Archive for Sexology, Berlin

- When Books Burn Archived 2018-04-12 at the Wayback Machine – University of Arizona multimedia exhibit.

- First homosexual movement

- Magnus Hirschfeld

- Sexology organizations

- Persecution of homosexuals in Nazi Germany

- Transgender studies

- Sexual orientation and medicine

- Scientific organizations established in 1919

- 1919 establishments in Germany

- Organizations disestablished in 1933

- 1933 disestablishments in Germany

- Medical research institutes in Germany

- Medical and health organisations based in Berlin

- Education in Nazi Germany

- Research institutes established in 1919

- Companies acquired from Jews under Nazi rule

Leave a Reply