Picture this: You’re strolling through a classical Greek agora, minding your own business, when BAM! You’re face-to-face with a square pillar sporting a head, maybe some pecs if you’re lucky, and – oh, hello there! – a rather prominent set of male genitalia at eye level. Talk about art that grabs your attention!

These saucy sculptures were supposedly named after Hermes, the god of boundaries, travel, and mischief. But let’s be real – they could’ve just as easily been called “blockheads with bits” given their connection to the Greek word for “blocks of stone.” It’s as if some ancient artist looked at a chunk of marble and thought, “You know what this needs? A face. And genitals. Definitely genitals.”

And let’s not forget the oil rubdowns and garland adornments. These statues were treated better than most people! It’s like a spa day, but for stone phalluses. Only in ancient Greece, folks! Feeling a bit down on your luck? Give that thing a rub, and watch your fortunes rise! The tradition of rubbing for luck persists today. Just ask the poor bronze boar in Florence, whose snout has been polished to a shine by eager tourists. Somehow, I don’t think that’s quite what the ancient Greeks had in mind, but hey, times change!

In Athens, these statues were more popular than gyros. They lined the streets, guarded homes, and even hung out in gyms. Talk about motivation for your workout! Nothing says “feel the burn” quite like a bearded god with exposed genitals cheering you on. These cheeky charmers were the Swiss Army knives of the ancient world. Need protection from evil spirits? Herma’s got you covered. Lost your way? Let herma point you in the right direction.

The Romans, never ones to pass up a good idea (or a risqué statue), adopted these titillating totems and called them “mercuriae.” Because nothing says “Welcome to Rome” like a stone pillar with a package, am I right?

But wait, it gets better! The Renaissance, that bastion of high culture and refined tastes, decided to revive this tradition. Imagine the conversation:

“What shall we use to adorn our gardens and palaces?”

“How about those Greek statues with the naughty bits?”

“Brilliant! Let’s call them ‘term figures’ to sound fancy.”

In conclusion, hermae are the ultimate proof that even in the loftiest realms of classical art, someone, somewhere, was thinking, “You know what would make this better? Genitals.” And for that, we salute them! It’s a testament to the enduring human appreciation for combining the highbrow with the lowbrow, the sacred with the profane, the head with the… well, you get the idea.

The Trial of Alcibiades – A tale so ridiculous it could only come from ancient Athens

It’s 415 BC, and Athens is buzzing with excitement for their upcoming Sicilian vacation – I mean, expedition. But on the eve of departure, someone decides to play a prank worthy of a frat house initiation. All the hermai – those phallic statues that apparently bring good luck (go figure) – get their stone manhoods lopped off.

The Athenians, being the chill, rational people they were, immediately jumped to the only logical conclusion: It must be a conspiracy to sabotage their war effort! Because nothing says “I’m going to destroy Athens” like dejunking some statues, right?

Enter Alcibiades, the Brad Pitt of ancient Greece. Handsome, charismatic, and with more enemies than you can shake a broken herma at. His rivals, seeing an opportunity juicier than a ripe olive, accused him of not just the herma-cide, but also of mocking sacred mysteries. Gasp! The horror!

Alcibiades, being the stand-up guy he was, said, “Sure, let’s have a trial. I’m innocent!” But his enemies, proving that political scheming is truly timeless, said, “Nah, you go on your little boat trip. We’ll just wait until you’re gone to condemn you to death. No biggie!” So off sails Alcibiades, blissfully unaware that back home, he’s being turned into Ancient Greece’s Most Wanted. By the time he hears about his death sentence, he’s probably sipping ouzo on a Sicilian beach.

The moral of the story? No idea.

Other Notes

In the earliest times Greek divinities were worshipped in the form of a heap of stones or a shapeless column of stone or wood. In many parts of Greece there were piles of stones by the sides of roads, especially at their crossings, and on the boundaries of lands. The religious respect paid to such heaps of stones, especially at the meeting of roads, is shown by the custom of each passer-by throwing a stone on to the heap or anointing it with oil. Later there was the addition of a head and phallus to the column, which became quadrangular (the number four was sacred to Hermes).

Before his role as protector of merchants and travelers, Hermes was a phallic god, associated with fertility, luck, roads and borders. His name perhaps comes from the word herma, referring to a square or rectangular pillar of stone, terracotta, or bronze.

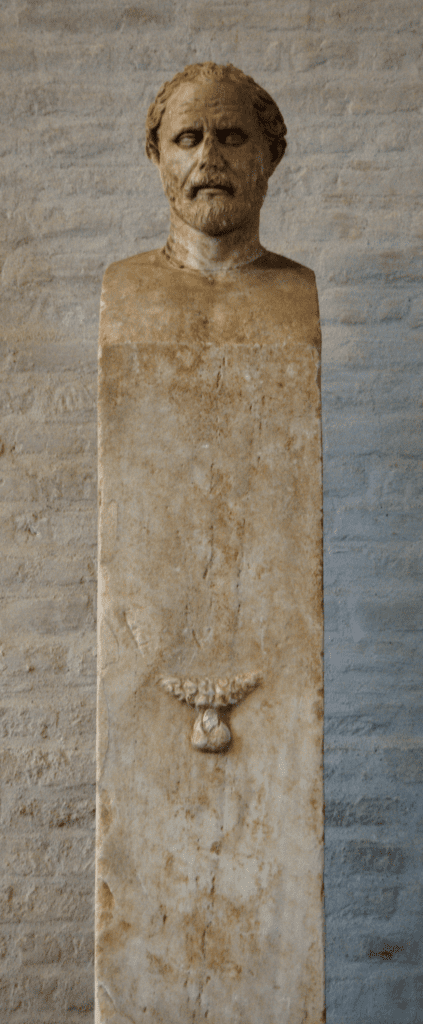

In Roman and Renaissance versions, the body was often shown from the waist up. The form was also used for portrait busts of famous public figures, especially writers like Socrates and Plato. Sappho appears on Ancient Greek herms, and anonymous female figures were often used from the Renaissance on, when herms were often attached to walls as decoration.

Leave a Reply