An echinoderm is any member of the phylum Echinodermata. The adults are recognisable by their (usually five-point) radial symmetry, and include starfish, brittle stars, sea urchins, sand dollars, and sea cucumbers, as well as the sea lilies or “stone lilies”. Adult echinoderms are found on the sea bed at every ocean depth, from the intertidal zone to the abyssal zone. The phylum contains about 7,000 living species, making it the second-largest grouping of deuterostomes, after the chordates.

- “echinoderm”. Dictionary.com Unabridged (Online). n.d.

- Hall, Danielle. “Echinoderms | Smithsonian Ocean”. ocean.si.edu. Retrieved 31 March 2023.

- “echinoderm”. Online Etymology Dictionary.

Sexual reproduction

Echinoderms become sexually mature after approximately two to three years, depending on the species and the environmental conditions. Almost all species have separate male and female sexes, though some are hermaphroditic. The eggs and sperm cells are typically released into open water, where fertilisation takes place. The release of sperm and eggs is synchronised in some species, usually with regard to the lunar cycle. In other species, individuals may aggregate during the reproductive season, increasing the likelihood of successful fertilisation. Internal fertilisation has been observed in three species of sea star, three brittle stars and a deep water sea cucumber. Even at abyssal depths, where no light penetrates, echinoderms often synchronise their reproductive activity.

- Young, Craig M.; Eckelbarger, Kevin J. (1994). Reproduction, Larval Biology, and Recruitment of the Deep-Sea Benthos. Columbia University Press. pp. 179–194. ISBN 0231080042.

Some echinoderms brood their eggs. This is especially common in cold water species where planktonic larvae might not be able to find sufficient food. These retained eggs are usually few in number and are supplied with large yolks to nourish the developing embryos. In starfish, the female may carry the eggs in special pouches, under her arms, under her arched body, or even in her cardiac stomach. Many brittle stars are hermaphrodites; they often brood their eggs, usually in special chambers on their oral surfaces, but sometimes in the ovary or coelom. In these starfish and brittle stars, development is usually direct to the adult form, without passing through a bilateral larval stage. A few sea urchins and one species of sand dollar carry their eggs in cavities, or near their anus, holding them in place with their spines. Some sea cucumbers use their buccal tentacles to transfer their eggs to their underside or back, where they are retained. In a very small number of species, the eggs are retained in the coelom where they develop viviparously, later emerging through ruptures in the body wall. In some crinoids, the embryos develop in special breeding bags, where the eggs are held until sperm released by a male happens to find them.

- Ruppert, Fox & Barnes 2004, pp. 887–888.

- Ruppert, Fox & Barnes 2004, p. 895.

- Ruppert, Fox & Barnes 2004, p. 888.

- Ruppert, Fox & Barnes 2004, p. 908.

- Ruppert, Fox & Barnes 2004, p. 916.

- Ruppert, Fox & Barnes 2004, p. 922.

Asexual reproduction

See also: § Regeneration

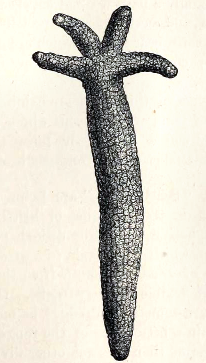

One species of seastar, Ophidiaster granifer, reproduces asexually by parthenogenesis. In certain other asterozoans, adults reproduce asexually until they mature, then reproduce sexually. In most of these species, asexual reproduction is by transverse fission with the disc splitting in two. Both the lost disc area and the missing arms regrow, so an individual may have arms of varying lengths. During the period of regrowth, they have a few tiny arms and one large arm, and are thus often known as “comets”.

- Yamaguchi, M.; J. S. Lucas (1984). “Natural parthenogenesis, larval and juvenile development, and geographical distribution of the coral reef asteroid Ophidiaster granifer“. Marine Biology. 83 (1): 33–42. doi:10.1007/BF00393083. S2CID 84475593.

- McGovern, Tamara M. (5 April 2002). “Patterns of sexual and asexual reproduction in the brittle star Ophiactis savignyi in the Florida Keys” (PDF). Marine Ecology Progress Series. 230: 119–126. Bibcode:2002MEPS..230..119M. doi:10.3354/meps230119. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- Monks, Sarah P. (1 April 1904). “Variability and Autotomy of Phataria“. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. 56 (2): 596–600. JSTOR 4063000.

- See last paragraph in review above AnalysisHotchkiss, Frederick H. C. (1 June 2000). “On the Number of Rays in Starfish”. American Zoologist. 40 (3): 340–354. doi:10.1093/icb/40.3.340.

- Fisher, W. K. (1 March 1925). “Asexual Reproduction in the Starfish, Sclerasterias“ (PDF). Biological Bulletin. 48 (3): 171–175. doi:10.2307/1536659. JSTOR 1536659. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 15 July 2011.

Adult sea cucumbers reproduce asexually by transverse fission. Holothuria parvula uses this method frequently, splitting into two a little in front of the midpoint. The two halves each regenerate their missing organs over a period of several months, but the missing genital organs are often very slow to develop.

- Kille, Frank R. (1942). “Regeneration of the Reproductive System Following Binary Fission in the Sea-Cucumber, Holothuria parvula (Selenka)” (PDF). Biological Bulletin. 83 (1): 55–66. doi:10.2307/1538013. JSTOR 1538013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

The larvae of some echinoderms are capable of asexual reproduction. This has long been known to occur among starfish and brittle stars, but has more recently been observed in a sea cucumber, a sand dollar and a sea urchin. This may be by autotomising parts that develop into secondary larvae, by budding, or by splitting transversely. Autotomised parts or buds may develop directly into fully formed larvae, or may pass through a gastrula or even a blastula stage. New larvae can develop from the preoral hood (a mound like structure above the mouth), the side body wall, the postero-lateral arms, or their rear ends.

- Eaves, Alexandra A.; Palmer, A. Richard (11 September 2003). “Reproduction: Widespread cloning in echinoderm larvae”. Nature. 425 (6954): 146. Bibcode:2003Natur.425..146E. doi:10.1038/425146a. hdl:10402/era.17195. PMID 12968170. S2CID 4430104.

- Jaeckle, William B. (1 February 1994). “Multiple Modes of Asexual Reproduction by Tropical and Subtropical Sea Star Larvae: An Unusual Adaptation for Genet Dispersal and Survival” (PDF). Biological Bulletin. 186 (1): 62–71. doi:10.2307/1542036. JSTOR 1542036. PMID 29283296. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 13 July 2011.

- Vaughn, Dawn (October 2009). “Predator-Induced Larval Cloning in the Sand Dollar Dendraster excentricus: Might Mothers Matter?”. Biological Bulletin. 217 (2): 103–114. doi:10.1086/BBLv217n2p103. PMID 19875816. S2CID 26030855.

Cloning is costly to the larva both in resources and in development time. Larvae undergo this process when food is plentiful or temperature conditions are optimal. Cloning may occur to make use of the tissues that are normally lost during metamorphosis. The larvae of some sand dollars clone themselves when they detect dissolved fish mucus, indicating the presence of predators. Asexual reproduction produces many smaller larvae that escape better from planktivorous fish, implying that the mechanism may be an anti-predator adaptation.

- Vaughn, Dawn (October 2009). “Predator-Induced Larval Cloning in the Sand Dollar Dendraster excentricus: Might Mothers Matter?”. Biological Bulletin. 217 (2): 103–114. doi:10.1086/BBLv217n2p103. PMID 19875816. S2CID 26030855.

- McDonald, Kathryn A.; Dawn Vaughn (1 August 2010). “Abrupt Change in Food Environment Induces Cloning in Plutei of Dendraster excentricus“. Biological Bulletin. 219 (1): 38–49. doi:10.1086/BBLv219n1p38. PMID 20813988. S2CID 24422314. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- Vaughn, Dawn; Richard R. Strathmann (14 March 2008). “Predators induce cloning in echinoderm larvae”. Science. 319 (5869): 1503. Bibcode:2008Sci…319.1503V. doi:10.1126/science.1151995. JSTOR 40284699. PMID 18339931. S2CID 206509992. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- Vaughn, Dawn (March 2010). “Why run and hide when you can divide? Evidence for larval cloning and reduced larval size as an adaptive inducible defense”. Marine Biology. 157 (6): 1301–1312. doi:10.1007/s00227-010-1410-z. S2CID 84336247.

Larval development

Development begins with a bilaterally symmetrical embryo, with a coeloblastula developing first. Gastrulation marks the opening of the “second mouth” that places echinoderms within the deuterostomes, and the mesoderm, which will host the skeleton, migrates inwards. The secondary body cavity, the coelom, forms by the partitioning of three body cavities. The larvae are often planktonic, but in some species the eggs are retained inside the female, while in some the female broods the larvae.

- Dorit, Walker & Barnes 1991, p. 778.

- Brusca, Moore & Shuster 2016, pp. 997–998.

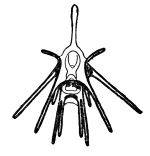

The larvae pass through several stages, which have specific names derived from the taxonomic names of the adults or from their appearance. For example, a sea urchin has an ‘echinopluteus’ larva while a brittle star has an ‘ophiopluteus’ larva. A starfish has a ‘bipinnaria‘ larva, which develops into a multi-armed ‘brachiolaria‘ larva. A sea cucumber’s larva is an ‘auricularia’ while a crinoid’s is a ‘vitellaria’. All these larvae are bilaterally symmetrical and have bands of cilia with which they swim; some, usually known as ‘pluteus’ larvae, have arms. When fully developed they settle on the seabed to undergo metamorphosis, and the larval arms and gut degenerate. The left hand side of the larva develops into the oral surface of the juvenile, while the right side becomes the aboral surface. At this stage the pentaradial symmetry develops.

- Dorit, Walker & Barnes 1991, p. 778.

- Brusca, Moore & Shuster 2016, pp. 997–998.

- van Egmond, Wim (1 July 2000). “Gallery of Echinoderm Larvae”. Microscopy UK. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

A plankton-eating larva, living and feeding in the water column, is considered to be the ancestral larval type for echinoderms, but in extant echinoderms, some 68% of species develop using a yolk-feeding larva. The provision of a yolk-sac means that smaller numbers of eggs are produced, the larvae have a shorter development period and a smaller dispersal potential, but a greater chance of survival.

- Uthicke, Sven; Schaffelke, Britta; Byrne, Maria (1 January 2009). “A boom–bust phylum? Ecological and evolutionary consequences of density variations in echinoderms”. Ecological Monographs. 79: 3–24. doi:10.1890/07-2136.1.

Related texts

- Brusca, Richard C.; Moore, Wendy; Shuster, Stephen M. (2016). Invertebrates (3rd ed.). Sunderland, Massachusetts. ISBN 978-1-60535-375-3. OCLC 928750550.

- Dorit, R. L.; Walker, W. F.; Barnes, R. D. (1991). Zoology, International edition. Saunders College Publishing. ISBN 978-0-03-030504-7.

- Ruppert, Edward E.; Fox, Richard, S.; Barnes, Robert D. (2004). Invertebrate Zoology (7th ed.). Cengage Learning. ISBN 81-315-0104-3.

External links

Wikispecies has information related to Echinodermata.

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Echinodermata.

- The Echinoid Directory from the Natural History Museum

- Echinodermata from the Tree of Life Web Project

- Echinoderms of the North Sea Archived 13 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Larval Echinodermata Fact Sheet

| Extant life phyla/divisions by domain |

|---|

Leave a Reply