Nasu (Also; Druj Nasu, Nasa, Nas, Nasuš) is the Avestan name of the female Zoroastrian demon (daeva) of corpse matter. She resides in the north (Vendidad. 7:2), where the Zoroastrian hell lies. Nasu takes the form of a fly, and is the manifestation of the decay and contamination of corpses (nasa) (Bundahishn. 28:29). When a death occurs, Nasu inhabits the corpse and acts as a catalyst for its decomposition. Nasu appears in various texts within the Avesta, notably the Vendidad, as the Vendidad gives particular focus to demons, purification rituals, and the disposal of corpses and other dead matter. Nasu is commonly considered “the greatest polluter of Ahura Mazda’s world.” Belief in Nasu has greatly influenced Zoroastrian funeral rites and burial ceremonies, as well as the general disdain for corpse matter that is harbored within Zoroastrian practitioners.

- Moazami, Mahnaz (2016). “Nasu”. www.iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2017-04-27.

Etymology

Druj, meaning “demoness,” is commonly used as a prefix for Nasu and other female daevas. Druj is a feminine Avestan language word meaning “falsehood,” the opposition of asha, or “truth.” Druj is the root for the adjective drəguuaṇt, meaning “owner of falsehood,” which “[designates] all beings who choose druj over asha.” Druj is used in various texts of the Avesta, with varying meanings. Depending upon the context, druj may refer to specific demons, or as a general term for that which is false, immoral, or unclean.

- Peterson, Joseph H. “Avestan Dictionary”. www.avesta.org. Retrieved 2017-04-27.

- Kohlberg, Etan (1998-12-15). “Evil”. www.iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2017-04-27.

The Avestan words nasu and nasa refer to corpses, or other solid dead matter such as nails and hair. Therefore, Nasu’s name literally means “corpse matter.”

- de Jong, Albert F. (1997). Traditions of the Magi: Zoroastrianism in Greek and Latin Literature. Brill. p. 137.

In the Vendidad

Contamination of the dead

Directly after death, as soon as the soul has left a corpse, “the druj Nasu rushes upon” the body, “in the shape of a raging fly, with knees and tail sticking out, droning without end” (Vd. 7:2). As soon as Nasu takes hold of a corpse, the body instantly becomes contaminated. If one comes into contact with a corpse, Nasu will emerge from the body and infect them, rendering them “unclean … for ever and ever” (Vd. 3:14). Nasu continues to inhabit the corpse until the sagdīd ritual is performed, during which a dog must look at the corpse, or until a carrion-eating bird or dog consumes the body, which causes her to return to her home in the north (Vd. 7:3).

Contamination of the living

Besides contaminating corpses upon death, Nasu also contaminates those who interact with corpse-matter in specific ways. In Vendidad 3:14, Ahura Mazda explains to the prophet Zoroaster that one must never carry a corpse on their own, lest Nasu’s infection transfers to them. If one carries a corpse alone, Nasu emerges “from the nose … , the eye, the tongue, the sexual organs, and the hinder parts” of the deceased, and “rushes upon [the corpse bearer] … [and stains him] even to the end of the nails, and he is unclean, thenceforth, forever and ever” (Vd. 3:14). In this case, there is no way to purify the infected individual. In order to avoid the spread of contamination, he must live in an enclosure where “the ground is the cleanest and the dryest and the least passed through by flocks and herds, by the fire of Ahura Mazda, by the consecrated bundles of Baresma,[a] and by the faithful” (Vd. 3:15). There, other Zoroastrians must provide him with “the coarsest food” and “the most worn-out clothes,” until he ages into an old man (hana) (Vd. 3:18-19). Once he is elderly, the infected must be beheaded, and his corpse is offered to the vultures. At this point, “he is absolved by his repentance” (Vd. 3:20-21).

- [a] Baresma: an Avestan language word for a wand of the Magi, made from a branch.

Nasu also attacks humans who consume the corpse of a dog or human, or those who put a corpse in water or fire. These individuals are considered unclean forever, with no option of repentance (Vd. 7:23-26). Nasu will also attack humans and dogs who are nearby a person at the time of their death (Vd. 5:27).

Purification

In some cases, a living individual who has been defiled by Nasu has a chance at regaining purity, if the proper purification rites are performed (Vd. 9:42). However, if the ritual is performed by an unqualified purifier, Nasu will grow stronger, and the contamination will heighten (Vd. 9:48).

In fargard 10 of the Vendidad, Ahura Mazda recommends recitation of certain verses from the Gathas to “fight against” Nasu and purify a contaminated individual (Vd. 10:1-12). Some verses must be recited twice (Yasna. 28:2, 35:2, 35:8, 39:4, 41:3, 41:5, 43:1, 47:1, 51:1, 53:1), thrice (Y. 27:14, 33:11, 35:5, 53:9), or four times (Y. 27:13, 34:15, 54:1).

The Sros baj, or “utterance against pollution,” an important daily recitation in honor of Sraosha, “is a powerful prophylactic prayer that protects one against decay and death.”

- Moazami, Mahnaz (2016). “Nasu”. www.iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2017-04-27.

Offspring

In fargard 18 of the Vendidad, Sraosha has a dialogue with Nasu. While striking Nasu, he asks her if she bears offspring without copulating with a man (Vd. 18:30). To this, Nasu responds that she is impregnated whenever practitioners of Zoroastrianism are greedy (Vd. 18:34), “emit seed” during sleep (Vd. 18:46), spill water (Vd. 18:40), or if they “[walk] without wearing the sacred girdle and the sacred shirt” (Vd. 18:54). Conversely, “the fruit of [her] womb” is destroyed every time one is generous to another Zoroastrian, or recites the Ahuna Vairya after emitting seed or spilling water.

Funeral rites and burial ceremonies

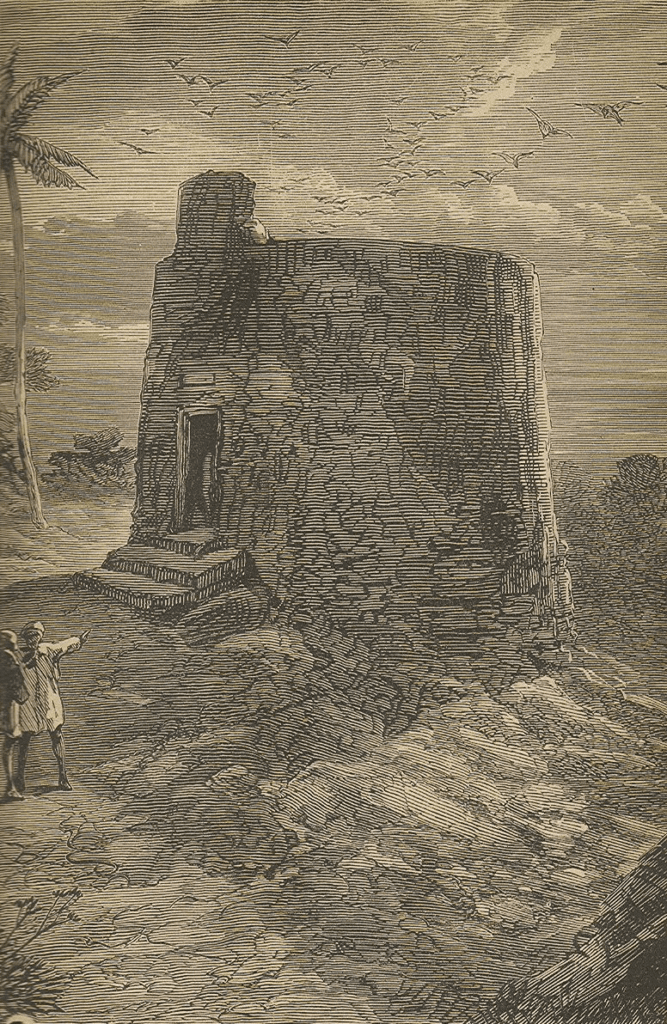

The belief that bodies are infested by Nasu upon death greatly influenced Zoroastrian burial ceremonies and funeral rites. Burial and cremation of corpses was prohibited, as such acts would defile the sacred creations of earth and fire respectively (Vd. 7:25). Burial of corpses was so looked down upon that the exhumation of “buried corpses was regarded as meritorious.” For these reasons, “Towers of Silence” were developed—open air, amphitheater like structures in which corpses were placed so carrion-eating birds could feed on them.

Russell, James R. “Burial iii. In Zoroastrianism”. www.iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2017-04-27.

Sagdīd, meaning “seen by a dog,” is a ritual that must be performed as promptly after death as possible. The dog is able to calculate the degree of evil within the corpse, and entraps the contamination so it may not spread further, expelling Nasu from the body (Denkard. 31). Nasu remains within the corpse until it has been seen by a dog, or until it has been consumed by a dog or a carrion-eating bird (Vd. 7:3). According to chapter 31 of the Denkard, the reasoning for the required consumption of corpses is that the evil influences of Nasu are contained within the corpse until, upon being digested, the body is changed from the form of nasa into nourishment for animals. The corpse is thereby delivered over to the animals, changing from the state of corrupted nasa to that of hixr, which is “dry dead matter,” considered to be less polluting.

- Moazami, Mahnaz (2016). “Nasu”. www.iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2017-04-27.

A path through which a funeral procession has traveled must not be passed again, as Nasu haunts the area thereafter, until the proper rites of banishment are performed (Vd. 8:15). Nasu is expelled from the area only after “a yellow dog with four eyes,[b] or a white dog with yellow ears” is walked through the path three times (Vd. 8:16). If the dog goes unwillingly down the path, it must be walked back and forth up to nine times to ensure that Nasu has been driven off (Vd. 8:17-18).

- [b] A dog with a spot above either eye.

Tower of Silence

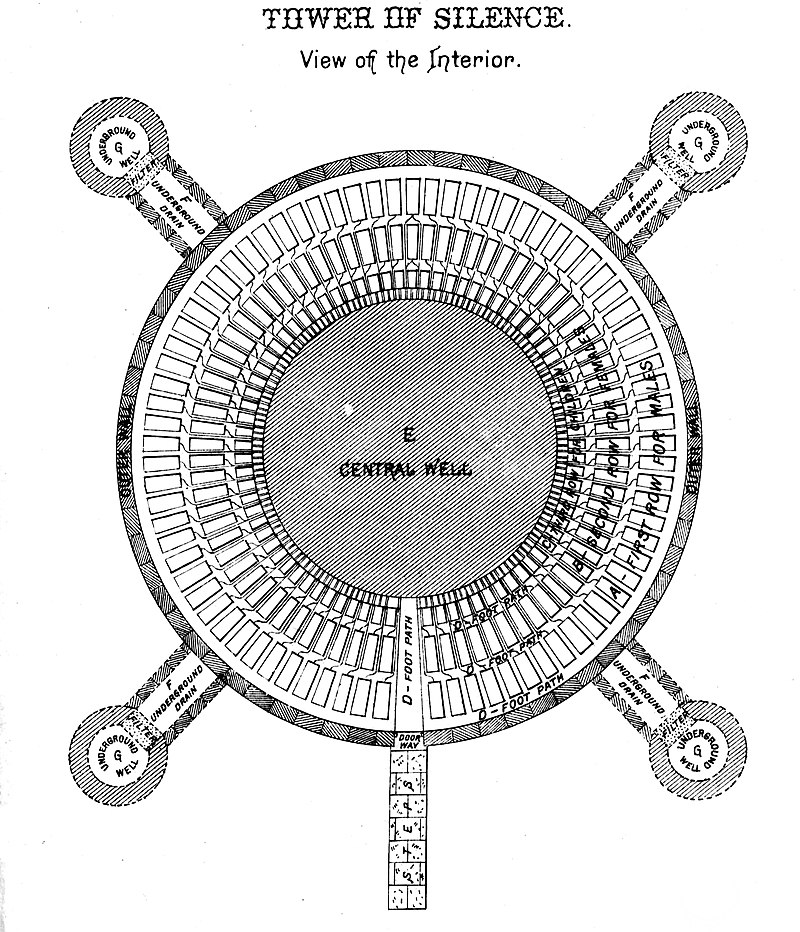

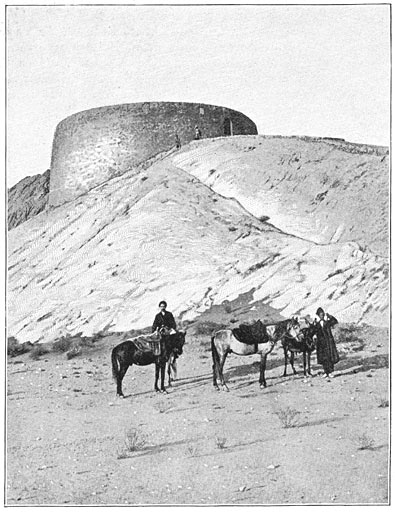

A dakhma (Persian: دخمه), also known as a Tower of Silence, is a circular, raised structure built by Zoroastrians for excarnation (that is, the exposure of human corpses to the elements for decomposition), in order to avert contamination of the soil and other natural elements by the dead bodies. Carrion birds, usually vultures and other scavengers, consume the flesh. Skeletal remains are gathered into a central pit where further weathering and continued breakdown occurs.

- Russell, James R. (1 January 2000). “BURIAL iii. In Zoroastrianism”. Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. IV/6. New York: Columbia University. pp. 561–563. ISSN 2330-4804. Archived from the original on 17 May 2013. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- Huff, Dietrich (2004). “Archaeological Evidence of Zoroastrian Funerary Practices”. In Stausberg, Michael (ed.). Zoroastrian Rituals in Context. Numen Book Series. Vol. 102. Leiden: Brill Publishers. pp. 593–630. doi:10.1163/9789047412502_027. ISBN 90-04-13131-0. ISSN 0169-8834. LCCN 2003055913.

- Malandra, W. W. (2013). “Iran”. In Spaeth, Barbette Stanley (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Ancient Mediterranean Religions. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 122. doi:10.1017/CCO9781139047784.009. ISBN 978-0-521-11396-0. LCCN 2012049271.

Ritual exposure by Iranian peoples

Main articles: Ancient Persia and Zoroastrians in Iran

Zoroastrian ritual exposure of the dead is first attested in the mid-5th century BCE Histories of Herodotus, an Ancient Greek historian who observed the custom amongst Iranian expatriates in Asia Minor; however, the use of towers is first documented in the early 9th century CE. In Herodotus’ account (in Histories i.140), the Zoroastrian funerary rites are said to have been “secret”; however they were first performed after the body had been dragged around by a bird or dog. The corpse was then embalmed with wax and laid in a trench.

- Russell, James R. (1 January 2000). “BURIAL iii. In Zoroastrianism”. Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. IV/6. New York: Columbia University. pp. 561–563. ISSN 2330-4804. Archived from the original on 17 May 2013. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- Huff, Dietrich (2004). “Archaeological Evidence of Zoroastrian Funerary Practices”. In Stausberg, Michael (ed.). Zoroastrian Rituals in Context. Numen Book Series. Vol. 102. Leiden: Brill Publishers. pp. 593–630. doi:10.1163/9789047412502_027. ISBN 90-04-13131-0. ISSN 0169-8834. LCCN 2003055913.

- Malandra, W. W. (2013). “Iran”. In Spaeth, Barbette Stanley (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Ancient Mediterranean Religions. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 122. doi:10.1017/CCO9781139047784.009. ISBN 978-0-521-11396-0. LCCN 2012049271.

- Stausberg, Michael (2004). “Bestattungsanlagen”. Die Religion Zarathushtras: Geschichte, Gegenwart, Rituale. Vol. 3. Stuttgart: Verlag W. Kohlhammer. pp. 204–245. ISBN 978-3170171206.

Writing on the culture of the Persians, Herodotus reports on the Persian burial customs performed by the magi, again, kept secret, according to his account. However, he writes that he knows they expose the body of male dead to dogs and birds of prey, then they cover the corpse in wax, and then it is buried. The Achaemenid custom for the dead is recorded in the regions of Bactria, Sogdia, and Hyrcania, but not in Western Iran.

- “Herodotus iii. Defining the Persians”. Encyclopaedia Iranica (online ed.). Archived from the original on 29 January 2019. Retrieved 24 January 2019.

- Encyclopaedia Iranica, edited by Ehsan Yar-Shater, Routledge & Kegan Paul Volume 6, Parts 1–3, p. 281a.

- Grenet, Frantz (January 2000). “BURIAL ii. Remnants of Burial Practices in Ancient Iran”. Encyclopaedia Iranica. Vol. IV. pp. 559–561. Fasc. 5–6.

The discovery of ossuaries in both Eastern and Western Iran dating to the 5th and 4th centuries BCE indicate that bones were sometimes isolated, but separation occurring through ritual exposure cannot be assumed: burial mounds, where the bodies were wrapped in wax, have also been discovered. The tombs of the Achaemenid emperors at Naqsh-e Rustam and Pasargadae likewise suggest non-exposure, at least until the bones could be collected. According to legend (incorporated by Ferdowsi into his Shahnameh; lit. ’The Book of Kings’), Zoroaster himself is interred in a tomb at Balkh (in present-day Afghanistan).

- Falk, Harry (1989), “Soma I and II”, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 52 (1): 77–90, doi:10.1017/s0041977x00023077, S2CID 146512196

The Byzantine historian Agathias has described the Zoroastrian burial of the Sasanian general Mihr-Mihroe: “the attendants of Mermeroes took up his body and removed it to a place outside the city and laid it there as it was, alone and uncovered according to their traditional custom, as refuse for dogs and horrible carrion”.

- Encyclopaedia Iranica, edited by Ehsan Yar-Shater, Routledge & Kegan Paul Volume 6, Parts 1–3, p. 281a.

- Boyce, Mary (October 31, 2011) [First published 15 December 1993]. “CORPSE, disposal of, in Zoroastrianism”. Encyclopaedia Iranica. Vol. VI. pp. 279–286. Fasc. 3.

Agathias described at second hand the disposal of the body of the Persian general Mihr-Mihrōē, who died in 555: ‘Then the attendants of Mihr-Mihrōē took up his body and removed it to a place outside the city and laid it there as it was, alone and uncovered according to their traditional custom, as refuse for dogs and horrible carrion birds’

Towers are a much later invention and are first documented in the early 9th century CE. The funerary ritual customs surrounding that practice appear to date to the Sassanid ra (3rd–7th CE). They are known in detail from the supplement to the Shayest ne Shayest, the two Rivayat collections, and the two Saddars.

- Boyce, Mary (1975). “The Zoroastrian Funeral Rites”. A history of Zoroastrianism: Early period. Vol. 1. Leiden: Brill. pp. 156–165, 325–330. doi:10.1163/9789004294004_014. ISBN 9789004294004.

One of the earliest literary descriptions of such a building appears in the late 9th-century Epistles of Manushchihr, where the technical term is astodan, ‘ossuary’. Another term that appears in the 9th- to 10th-century texts of Zoroastrian tradition (the so-called “Pahlavi books“) is dakhmag; in its earliest usage, it referred to any place for the dead.

Rationale

The doctrinal rationale for exposure is to avoid contact with earth, water, or fire, all three of which are considered sacred in the Zoroastrian religion.

- Huff, Dietrich (2004). “Archaeological Evidence of Zoroastrian Funerary Practices”. In Stausberg, Michael (ed.). Zoroastrian Rituals in Context. Numen Book Series. Vol. 102. Leiden: Brill Publishers. pp. 593–630. doi:10.1163/9789047412502_027. ISBN 90-04-13131-0. ISSN 0169-8834. LCCN 2003055913.

- Malandra, W. W. (2013). “Iran”. In Spaeth, Barbette Stanley (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Ancient Mediterranean Religions. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 122. doi:10.1017/CCO9781139047784.009. ISBN 978-0-521-11396-0. LCCN 2012049271.

Zoroastrian tradition considers human cadavers and animal corpses (in addition to cut hair and nail parings) to be nasu, i.e. unclean, polluting. Specifically, Nasu the corpse demon (daeva), is believed to rush into the body and contaminate everything it comes into contact with. For this reason, the Vīdēvdād (an ecclesiastical code whose title means, ‘given against the demons’) has rules for disposing of the dead as safely as possible. Moreover, the Vīdēvdād requires that graves, and raised tombs as well, must be destroyed.

- Russell, James R. (1 January 2000). “BURIAL iii. In Zoroastrianism”. Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. IV/6. New York: Columbia University. pp. 561–563. ISSN 2330-4804. Archived from the original on 17 May 2013. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- Huff, Dietrich (2004). “Archaeological Evidence of Zoroastrian Funerary Practices”. In Stausberg, Michael (ed.). Zoroastrian Rituals in Context. Numen Book Series. Vol. 102. Leiden: Brill Publishers. pp. 593–630. doi:10.1163/9789047412502_027. ISBN 90-04-13131-0. ISSN 0169-8834. LCCN 2003055913.

- Malandra, W. W. (2013). “Iran”. In Spaeth, Barbette Stanley (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Ancient Mediterranean Religions. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 122. doi:10.1017/CCO9781139047784.009. ISBN 978-0-521-11396-0. LCCN 2012049271.

- Boyce, Mary (1975). “The Zoroastrian Funeral Rites”. A history of Zoroastrianism: Early period. Vol. 1. Leiden: Brill. pp. 156–165, 325–330. doi:10.1163/9789004294004_014. ISBN 9789004294004.

- Brodd, Jeffrey (2003). World Religions. Winona, MN, USA: Saint Mary’s Press. ISBN 978-0-88489-725-5.

To preclude the pollution of the sacred elements: earth (zām), water (āpas), and fire (ātar), the bodies of the dead are placed at the top of towers and there exposed to the sun and to scavenging birds and necrophagous animals such as wild dogs. Thus, as an early-20th-century Secretary of the Bombay Parsi community explained: “putrefaction with all its concomitant evils… is most effectually prevented.”

- Russell, James R. (1 January 2000). “BURIAL iii. In Zoroastrianism”. Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. IV/6. New York: Columbia University. pp. 561–563. ISSN 2330-4804. Archived from the original on 17 May 2013. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- Huff, Dietrich (2004). “Archaeological Evidence of Zoroastrian Funerary Practices”. In Stausberg, Michael (ed.). Zoroastrian Rituals in Context. Numen Book Series. Vol. 102. Leiden: Brill Publishers. pp. 593–630. doi:10.1163/9789047412502_027. ISBN 90-04-13131-0. ISSN 0169-8834. LCCN 2003055913.

- Malandra, W. W. (2013). “Iran”. In Spaeth, Barbette Stanley (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Ancient Mediterranean Religions. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 122. doi:10.1017/CCO9781139047784.009. ISBN 978-0-521-11396-0. LCCN 2012049271.

- Modi, Jivanji Jamshedji Modi (1928), The Funeral Ceremonies of the Parsees, Anthropological Society of Bombay, archived from the original on 2005-02-07, retrieved 2005-09-09 Here, Modi is quoting from a “short description of the tower with a plan as given by Mr. Nusserwanjee Byrawjee, the late energetic Secretary of the public charity funds and properties of the Parsi community.”

In current times

Structure and process

Modern-day towers, which are fairly uniform in their construction, have an almost flat roof, with the perimeter being slightly higher than the centre. The roof is divided into three concentric rings: the bodies of men are arranged around the outer ring, women in the second ring, and children in the innermost ring. The ritual precinct may be entered only by a special class of pallbearers, called nusessalars, from the Avestan: nasa a salar, consisting of the word elements, -salar (‘caretaker’) and nasa- (‘pollutants’).

Once the bones have been bleached by the sun and wind, which can take as long as a year, they are collected in an ossuary pit at the centre of the tower, where—assisted by lime—they gradually disintegrate, and the remaining material, along with rainwater run-off, seeps through multiple coal and sand filters before being eventually washed out to sea.

- Sunavala, Nergish (28 October 2014). “Defunct Tower of Silence lives on in the heart of an Andheri residential colony”. The Times of India. Retrieved 1 May 2022.

- Modi, Jivanji Jamshedji Modi (1928), The Funeral Ceremonies of the Parsees, Anthropological Society of Bombay, archived from the original on 2005-02-07, retrieved 2005-09-09

Iran

In the Iranian Zoroastrian tradition, the towers were built atop hills or low mountains in locations distant from population centres. In the early 20th century, Iranian Zoroastrians gradually discontinued their use and began to favour burial or cremation.[citation needed]

The decision to change the system was accelerated by three considerations: the first problem arose with the establishment of the Dar ul-Funun medical school. Since Islam considers dissection of corpses as an unnecessary form of mutilation, thus forbidding it,[citation needed] there were no corpses for study available through official channels. The towers were repeatedly broken into, much to the dismay of the Zoroastrian community.[citation needed] Secondly, while the towers had been built away from population centres, the growth of the towns led to the towers now being within city limits.[citation needed] Finally, many of the Zoroastrians found the system outdated. Following long negotiations between the anjuman societies of Yazd, Kerman, and Tehran, the latter gained a majority and established a cemetery some 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) from Tehran at Ghassr-e Firouzeh (Firouzeh’s Palace). The graves were lined with rocks and plastered with cement to prevent direct contact with the earth. In Yazd and Kerman, in addition to cemeteries, orthodox Zoroastrians continued to maintain a tower until the Iranian revolution of 1979, when ritual exposure was prohibited by law.[citation needed]

India

Following the rapid expansion of the Indian cities, the squat buildings are today in or near population centres, but separated from the metropolitan bustle by gardens or forests. In Parsi Zoroastrian tradition, exposure of the dead is also considered to be an individual’s final act of charity, providing the birds with what would otherwise be destroyed.

In the late 20th century and early 21st century the vulture population on the Indian subcontinent declined (see Indian vulture crisis) by over 97% as of 2008, primarily due to diclofenac poisoning of the birds following the introduction of that drug for livestock in the 1990s, until banned for cattle by the Government of India in 2006. The few surviving birds are often unable to fully consume the bodies. In 2001, Parsi communities in India were evaluating captive breeding of vultures and the use of “solar concentrators” (which are essentially large mirrors) to accelerate decomposition. Some have been forced to resort to burial, as the solar collectors work only in clear weather. Vultures used to dispose of a body in minutes, and no other method has proved fully effective.

- Tait, Malcolm (10 October 2004). “India’s vulture population is facing catastrophic collapse and with it the sacrosanct corporeal passing of the Parsi dead”. The Ecologist. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007.

- Adam, David (31 January 2006). “Cattle drug blamed as India’s vultures near extinction”. The Guardian.

- Swan, Gerry; Naidoo, Vinasan; Cuthbert, Richard; et al. (January 2006). “Removing the threat of diclofenac to critically endangered Asian vultures”. PLOS Biology. 4 (3): e66. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0040066. PMC 1351921. PMID 16435886.

- Srivastava, Sanjeev (18 July 2001), “Parsis turn to solar power”, BBC News South Asia, archived from the original on 30 June 2006, retrieved 9 September 2005

The right to use the Towers of Silence is a much-debated issue among the Parsi community. The facilities are usually managed by the anjumans, the predominantly conservative local Zoroastrian associations. These usually having five priests on a nine-member board. In accordance with Indian statutes, these associations have domestic authority over trust properties and have the right to grant or restrict entry and use, with the result that the associations frequently prohibit the use by the offspring of a “mixed marriage”, that is, where one parent is a Parsi and the other is not.

- Palsetia, Jesse S. (2001). “Epilogue: Identity and the Present-Day Parsis”. The Parsis of India: Preservation of identity in Bombay city. Leiden: Brill. pp. 320–337. ISBN 9789004491274.

The towers remain in use as sacred locations for the Parsi community, though non-members may not enter them. In Mumbai visitors are shown a model of a tower. Organized tours can be taken to the site.

- My Visit To The Tower Of Silence Helped Me Come To Terms With Death

- Tower of Silence, Sky Burial and Birds of Prey

- “Citizen groups oppose heritage tour of Parsi Tower of Silence”. Hindustan Times. New Delhi, India: HT Digital Streams Ltd. 10 December 2016.

- “Protests don’t hinder heritage walk at Tower of Silence”. Hindustan Times. 12 December 2016.

Architectural and functional features

- The towers are uniform in their construction.

- The roof of the tower is lower in the middle than the outer and is divided into three concentric circles.

- The dead bodies are placed on stone beds on the roof of the tower and there is a central ossuary pit, into which the bodies fall after eaten by vultures.

- The bodies disintegrate naturally assisted with lime and the remaining is washed off by rainwater into multiple filters of coal and sand, finally reaching the sea.

In popular culture

Nasu appears as a villain in eight games from the Megami Tensei video game franchise: Digital Devil Story: Megami Tensei, Digital Devil Story: Megami Tensei II, Kyūyaku Megami Tensei, Shin Megami Tensei: if…, Last Bible III, Ronde, Giten Megami Tensei: Tokyo Mokushiroku, and Revelations: Persona. In these games, she is either referred to as Druj (ドゥルジ, Duruji), Nasu (ナース, Nāsu), or Nasu Fly (ナース蝿, Nāsu Hae). In Shin Megami Tensei: if… Nasu is a boss, while she appears as lesser demons in the other games.

Nasu is a card in four battle RPG smartphone games for Android and IOS: Age of Ishtaria, Guardian Cross, Legend of the Cryptids, and Blood Brothers. In each of these games, she is called Druj Nasu.

A Druj Nasu is a type of div that players can encounter in the tabletop role-playing game, Pathfinder.

See also

- Fire temple, Zoroastrian place of worship

- Seth Modi Hirji Vachha, builder of the first Bombay (Mumbai) dakhma (1672)

- Sky burial

- Vāyu-Vāta, air (vāyu) as a sacred element; the Zoroastrian divinity of wind

- Angra Mainyu

- Daeva

- Excarnation

- Ritual purification

- Vendidad

Notes

- Baresma: an Avestan language word for a wand of the Magi, made from a branch.

- A dog with a spot above either eye.

References

- Moazami, Mahnaz (2016). “Nasu”. www.iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2017-04-27.

- Peterson, Joseph H. “Avestan Dictionary”. www.avesta.org. Retrieved 2017-04-27.

- Kohlberg, Etan (1998-12-15). “Evil”. www.iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2017-04-27.

- de Jong, Albert F. (1997). Traditions of the Magi: Zoroastrianism in Greek and Latin Literature. Brill. p. 137.

- Russell, James R. “Burial iii. In Zoroastrianism”. www.iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2017-04-27.

- Russell, James R. (1 January 2000). “BURIAL iii. In Zoroastrianism”. Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. IV/6. New York: Columbia University. pp. 561–563. ISSN 2330-4804. Archived from the original on 17 May 2013. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- Huff, Dietrich (2004). “Archaeological Evidence of Zoroastrian Funerary Practices”. In Stausberg, Michael (ed.). Zoroastrian Rituals in Context. Numen Book Series. Vol. 102. Leiden: Brill Publishers. pp. 593–630. doi:10.1163/9789047412502_027. ISBN 90-04-13131-0. ISSN 0169-8834. LCCN 2003055913.

- Malandra, W. W. (2013). “Iran”. In Spaeth, Barbette Stanley (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Ancient Mediterranean Religions. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 122. doi:10.1017/CCO9781139047784.009. ISBN 978-0-521-11396-0. LCCN 2012049271.

- Stausberg, Michael (2004). “Bestattungsanlagen”. Die Religion Zarathushtras: Geschichte, Gegenwart, Rituale. Vol. 3. Stuttgart: Verlag W. Kohlhammer. pp. 204–245. ISBN 978-3170171206.

- “Herodotus iii. Defining the Persians”. Encyclopaedia Iranica (online ed.). Archived from the original on 29 January 2019. Retrieved 24 January 2019.

- Encyclopaedia Iranica, edited by Ehsan Yar-Shater, Routledge & Kegan Paul Volume 6, Parts 1–3, p. 281a.

- Grenet, Frantz (January 2000). “BURIAL ii. Remnants of Burial Practices in Ancient Iran”. Encyclopaedia Iranica. Vol. IV. pp. 559–561. Fasc. 5–6.

- Falk, Harry (1989), “Soma I and II”, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 52 (1): 77–90, doi:10.1017/s0041977x00023077, S2CID 146512196

- Boyce, Mary (October 31, 2011) [First published 15 December 1993]. “CORPSE, disposal of, in Zoroastrianism”. Encyclopaedia Iranica. Vol. VI. pp. 279–286. Fasc. 3.

Agathias described at second hand the disposal of the body of the Persian general Mihr-Mihrōē, who died in 555: ‘Then the attendants of Mihr-Mihrōē took up his body and removed it to a place outside the city and laid it there as it was, alone and uncovered according to their traditional custom, as refuse for dogs and horrible carrion birds’

- Boyce, Mary (1975). “The Zoroastrian Funeral Rites”. A history of Zoroastrianism: Early period. Vol. 1. Leiden: Brill. pp. 156–165, 325–330. doi:10.1163/9789004294004_014. ISBN 9789004294004.

- Brodd, Jeffrey (2003). World Religions. Winona, MN, USA: Saint Mary’s Press. ISBN 978-0-88489-725-5.

- Modi, Jivanji Jamshedji Modi (1928), The Funeral Ceremonies of the Parsees, Anthropological Society of Bombay, archived from the original on 2005-02-07, retrieved 2005-09-09

- Here, Modi is quoting from a “short description of the tower with a plan as given by Mr. Nusserwanjee Byrawjee, the late energetic Secretary of the public charity funds and properties of the Parsi community.”

- Sunavala, Nergish (28 October 2014). “Defunct Tower of Silence lives on in the heart of an Andheri residential colony”. The Times of India. Retrieved 1 May 2022.

- Modi, Jivanji Jamshedji Modi (1928), The Funeral Ceremonies of the Parsees, Anthropological Society of Bombay, archived from the original on 2005-02-07, retrieved 2005-09-09

- Tait, Malcolm (10 October 2004). “India’s vulture population is facing catastrophic collapse and with it the sacrosanct corporeal passing of the Parsi dead”. The Ecologist. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007.

- Adam, David (31 January 2006). “Cattle drug blamed as India’s vultures near extinction”. The Guardian.

- Swan, Gerry; Naidoo, Vinasan; Cuthbert, Richard; et al. (January 2006). “Removing the threat of diclofenac to critically endangered Asian vultures”. PLOS Biology. 4 (3): e66. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0040066. PMC 1351921. PMID 16435886.

- Srivastava, Sanjeev (18 July 2001), “Parsis turn to solar power”, BBC News South Asia, archived from the original on 30 June 2006, retrieved 9 September 2005

- Palsetia, Jesse S. (2001). “Epilogue: Identity and the Present-Day Parsis”. The Parsis of India: Preservation of identity in Bombay city. Leiden: Brill. pp. 320–337. ISBN 9789004491274.

- My Visit To The Tower Of Silence Helped Me Come To Terms With Death

- Tower of Silence, Sky Burial and Birds of Prey

- “Citizen groups oppose heritage tour of Parsi Tower of Silence”. Hindustan Times. New Delhi, India: HT Digital Streams Ltd. 10 December 2016.

- “Protests don’t hinder heritage walk at Tower of Silence”. Hindustan Times. 12 December 2016.

Further reading

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Towers of Silence.

Look up tower of silence in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- Vendidad Fargard 5, Purity Laws, as translated by James Darmesteter

- Wadia, Azmi (2002), “Evolution of the Towers of Silence and their Significance”, in Godrej, Pheroza J.; Mistree, Firoza Punthakey (eds.), A Zoroastrian Tapestry, New York: Mapin

- Excerpted in “A Zoroastrian Tapestry (book extract)”. The Hindu – Sunday Magazine. 21 July 2002. Archived from the original on 7 January 2003.

- Modi, Jivanji Jamshedji (2011) [Reprint of 2nd edition (1937), originally published by Jehangir B. Karani’s Sons: Bombay]. Peterson, Joseph H. (ed.). The Religious Ceremonies and Customs of the Parsees (PDF). Kasson, Minnesota, US: Avesta.org.

- Lucarelli, Fosco (February 9, 2012). “Towers of Silence: Zoroastrian Architectures for the Ritual of Death”, Socks-Studio

- Kotwal, Firoze M.; Mistree, Khojeste P. (2002), “Protecting the Physical World”, in Godrej, Pheroza J.; Mistree, Firoza Punthakey (eds.), A Zoroastrian Tapestry, New York: Mapin, pp. 337–365

- منصور خواجه پور [Khajepour, Mansour]; زینب رئوفی [Raoufi, Zeinab] (June 2018). “راهبردی نظری برای باززندهسازی دخمههای زرتشتیان در ایران (نمونۀ موردی : دخمۀ زرتشتیان کرمان)” [A Theoretical Approach to Restoration of Zoroastrians’ Tower of Silence (Dakhma) in Iran (A Case study of tower of silence of Kerman)]. ماهنامه علمی پژوهشی باغ نظر [Bagh-e-Nazar: The Scientific Journal of NAZAR research center for Art, Architecture & Urbanism] (in Persian and English). 15 (61): 57–70. doi:10.22034/bagh.2018.63865.

- Harris, Gardiner (29 November 2012). “Giving New Life to Vultures to Restore a Human Ritual of Death”, The New York Times

- Dunning, Brian (August 14, 2012). “Skeptoid #323: 8 Spooky Places, and Why They’re Like That”. Skeptoid.

1. Zoroastrian Towers of Silence

- Boyce, Mary (1979), Zoroastrians: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices, London: Routledge, pp. 156–162

- Boyce, Mary (1996), “Death among Zoroastrians”, Encyclopædia Iranica, vol. 7, Cosa Mesa: Mazda

Disambiguation

Nasu may also refer to:

- Nasu people, an ethnic group in China

- New American Standard Bible Update

- Nasu (那須), a traditional name for a region in northern Tochigi Prefecture, Japan. It is also in the names of several places:

- Nasushiobara, Tochigi, a city

- Nasukarasuyama, Tochigi, a city

- Nasu, Tochigi, a town

- Nasu District, Tochigi

- Nasu Highlands, an open area

- Nasu Mountains, volcanic peaks in the region

- Nasushiobara Station, a railway station takes its name from the region

- Nasu (茄子 or ナス), the Japanese word for eggplant

- Nasu (manga), a 2000 manga series authored by Iou Kuroda

- Nasu: Summer in Andalusia, a 2003 animated film adapted from Nasu

- Jinyu Nasu (那須 甚有, born 1999), Japanese footballer

- Kinoko Nasu (born 1973), Japanese author, co-founder of TYPE-MOON

- Sisu Nasu, military all-terrain transport vehicle of Finnish origin

- Nasu language, a Loloish language spoken by Yi people of China

- National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine

Leave a Reply