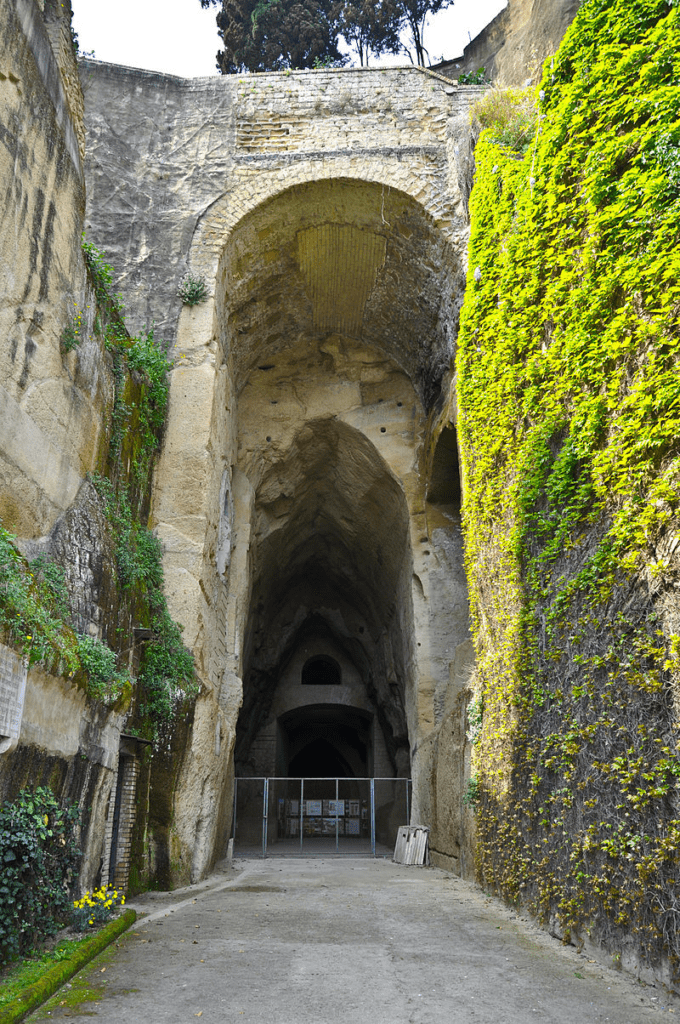

The Crypta Neapolitana (Latin for “Neapolitan crypt”) is an ancient Roman road tunnel near Naples, Italy. It was built in 37 BC and is over 700 metres long.

- Crypta Neapolitana (Naples, Italy), A Multidisciplinary Underground Heritage Site Graziano Ferrari1, Raffaella Lamagna1, Elena Rognoni1, Hypogea 2019 – Proceedings Of International Congress Of Speleology In Artificial Cavities – Dobrich, MAY 20-25 2019

The tunnel connected Naples with the so-called Phlegrean Fields and the town of Pozzuoli along the road known as the via Domiziana.

Via Domiziana is the modern name for the Via Domitiana in the Campania region of Italy, a major Roman road built in 95 AD under (and named for) the emperor, Domitian, to facilitate access to and from the important ports of Puteoli (modern Pozzuoli) and Portus Julius (home port of the western Imperial fleet, consisting of the waters around Baiae and Cape Misenum) in the Gulf of Naples. The Via Domitiana was not built from scratch, but was based on an existing road and it also used works undertaken in the Neronian period for the construction of the Fossa Neronis (the canal intended to connect Rome to Pozzuoli). The road left the Appian Way at Formiae or Sinuessa. It followed the coast and crossed the rivers Savona and Volturna, passed through an area of coastal lagoons by Linterne and Cumae and ended in Pozzuoli. In 102 Trajan extended the Via Domitiana to Naples. It was damaged by Alaric in 420 AD and ultimately destroyed by Gaiseric in 455 AD. It was partially restored under various rulers of the Kingdom of Naples in the Middle Ages and in its modern guise is a major coast road leading north from Naples. Statius wrote an entire poem on the theme of Via Domitiana. He recalled the progress made by the new road and praised the Emperor. The poem is also an interesting testimony on the construction of roads under the Roman Empire.

- di Mauro, Leonardo (2003). Ferrari-Bravo, Anna (ed.). Naples: The City and Its Famous Bay. Milan, Italy: Touring Club of Italy. p. 12. ISBN 88-365-2836-8.

- Balsdon, John (1970). Rome: the story of an empire. World University Library. New York: McGraw Hill. p. 64. OCLC 112699.

- The remains of the Roman bridge on the Volturna, inserted in the mediaeval fortress, are still visible in Castel Volturno

- Statius: Silvae , IV, 3

- Johannes JL Smolenaars, “Ideology and Poetics along the Via Domitiana: Statius Silvae 4.3”, in Flavian Poetry , ed. by Ruurd R. Nauta, Harm-Jan van Dam, and Johannes JL Smolenaars (“Mnemosyne Supplementa”), Leiden, Brill, 2006, pp. 223-244. ( ISBN 90-04-14794-2 )

The “Neapolitan Crypt” is also called, generically, a “grotta” (grotto) and is the reference in various place names in the area such as Piedigrotta (“at the foot of the grotto”) and Fuorigrotta (“at the other end of the grotto”). The tunnel, though ancient, was kept up and even expanded in recent centuries and remained in sporadic use until quite late, until superseded by two nearby modern vehicular tunnels around 1900.

Geography

The eastern entrance (on the Naples side) lies in the Vergiliano park of Piedigrotta (“at the foot of the grotta”); the western end is in the area now called Fuorigrotta (“outside the grotta”).

The site is also noteworthy for the presence of the so-called Virgil’s tomb, as well as the tomb of the Italian poet Giacomo Leopardi.

Virgil was the object of literary admiration and veneration before his death. In the following centuries and particularly in the Middle Ages his name became associated with legends of miraculous powers and his tomb the object of pilgrimages and pagan veneration. At the time of Virgil’s death, a large bay tree was near the entrance. According to a local legend, it died when Dante died, and Petrarch planted a new one; because visitors took branches as souvenirs the second tree died as well. When Virgil died at Brindisi in 19 BCE, he asked that his ashes be taken back to his villa just outside Naples. There a shrine was created for him, and sacred rites were held every year on his birthday.[citation needed] He was given the rites of a hero, at whose tomb the devout may find protection and counsel. Virgil’s tomb became a place of pilgrimage for many centuries, with Petrarch and Boccaccio being among those who visited the tomb. The tomb still contains a tripod burner originally dedicated to Apollo. There are no human remains in the tomb, however, as Virgil’s ashes were lost while being moved during the Middle Ages.

- Trapp, J. B. (1984). “The Grave of Vergil”. Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes. 47: 1–31. doi:10.2307/751436. JSTOR 751436. S2CID 195009111.

- Ziolkowski, Jan M.; Putnam, Michael C. J. (2008). The Virgilian Tradition: The First Fifteen Hundred Years. Yale University Press. pp. xxxiv–xxxv. ISBN 978-0300108224. Retrieved November 11, 2013.

- Suetonius: The Life of Virgil

- Oggetto Artistico : Virgil’s Tomb Archived 2012-04-02 at the Wayback Machine Parco della Tomba di Virgilio. Circuito informativo regionale della Campania per i Beni Culturali e Paesaggistici.

History

Naples and Pozzuoli were separated by a great impenetrable marsh: the first road between the two cities was probably built by the Greeks and was narrow and indirect.

The first Roman road connecting Neapolis and the Phlegrean fields, the via (Antiniana) per colles, was built at the beginning of the 1st century BC and followed the easiest route but it was nevertheless still long, difficult, tortuous and traversed steep hills. It climbed the hills of Vomero and came back down towards Fuorigrotta arriving at the modern Via Terracina from where it continued to the ports of Puteoli and Cumae. As Puteoli and associated trade between the two cities grew, the old road needed to be improved, so the tunnel shortened the route and avoided several hills.

The tunnel was first built by the architect Lucius Cocceius Auctus for Agrippa during the civil war between Octavian and Sextus Pompeius in c.37 BC. The new road, called via per cryptam, turned north at the west end of the tunnel, heading towards Via Leopardi and reconnecting with the old road, the via Neapolis-Puteoli, at the top of Via Terracina where a way-station (tabernae) and adjoining thermal spa complex has been excavated.

- Lucio Amato, Aldo Evangelista, Marco V Nicotera, C Viggiani: THE CRYPTA NEAPOLITANA; A ROMAN TUNNEL OF THE EARLY IMPERIAL AGE, January 2000, Conference: Unesco 2000

The tunnel is one of 4 road tunnels built in the area by Cocceius: others are the Grotta di Seiano (tunnel of Sejanus) in Posillipo, the Grotta di Cocceio from Lake Avernus to Cumae, and the Crypta Romana from Cumae to its port, as part of a network of military infrastructures including construction of the Portus Julius.

The Aqua Augusta (Serino) aqueduct was built later in parallel to the road tunnel.

The tunnel was still in use as a roadway until superseded by two modern tunnels in the early 20th century, and shows extensive restoration done by the architects of the Bourbon dynasty of Naples. During the Second World War it was used as a bomb shelter for the inhabitants of Bagnoli; the war and some landslides during the fifties put it back into a state of neglect. Today it has been restored as an archaeological site.

According to mediaeval legend, the tunnel was built by the poet Virgil in a single night.

- Lancaster, Jordan (2005), In the Shadow of Vesuvius: A Cultural History of Naples, I.B.Tauris, p. 48, ISBN 1-85043-764-5, retrieved 2008-04-30

Parco Vergiliano

Parco Vergiliano (not to be confused with Parco Virgiliano at Posillipo) is a public park in Naples, southern Italy. It is located directly across from the Mergellina railway station and in back of the church of Santa Maria di Piedigrotta.

It is a relatively small space and easy to overlook. The site is a monument tribute to the poet Virgil, and a plaque claims that the site is the final resting place of the poet. The site is at the eastern opening of the so-called Neapolitan Crypt, an ancient Roman tunnel that led through the Posillipo hill to connect to a major road leading north to Rome, itself. Legend says that the poet—also renowned as a sorcerer—called the tunnel into existence by his powers. The tunnel was probably the work of Lucius Cocceus Auctus, the Roman engineer who built the nearby Seiano Grotto and many of the fortifications of the Roman Imperial Port in Baia. Parco Virgiliano also contains the authenticated tomb of a more recent poet, Giacomo Leopardi, who died in Naples in 1837.

Parco Virgiliano

Parco Virgiliano (the Park of Remembrance) is a scenic park located on the hill of Posillipo, Naples, Italy. The Park serves as a green oasis, built on the tufa stone typical to the coast of Posillipo.

A series of terraces overlooking the whole Gulf of Naples provides the park with a unique array of impressive vistas, including views of the coasts of Amalfi and Sorrento, Mount Vesuvius, Gaiola Bay, Pollione’S amphitheater, Trentaremi Bay, Nisida island, the factory neighbourhood of Bagnoli, Pozzuoli, Baia, Bacoli, Monte di Procida and the beautiful islands of Ischia, Capri and Procida.

The park offers several playgrounds designed for children of various age-groups, as well as many kiosks which during the summer nights are often packed with youngsters just relaxing. The park also has a small amphitheater, where events are organized in the summers.

See also

References

- Crypta Neapolitana (Naples, Italy), A Multidisciplinary Underground Heritage Site Graziano Ferrari1, Raffaella Lamagna1, Elena Rognoni1, Hypogea 2019 – Proceedings Of International Congress Of Speleology In Artificial Cavities – Dobrich, MAY 20-25 2019

- Strabo , Geography , book V, chap. 4, par. 5

- Lucio Amato, Aldo Evangelista, Marco V Nicotera, C Viggiani: THE CRYPTA NEAPOLITANA; A ROMAN TUNNEL OF THE EARLY IMPERIAL AGE, January 2000, Conference: Unesco 2000

- Lancaster, Jordan (2005), In the Shadow of Vesuvius: A Cultural History of Naples, I.B.Tauris, p. 48, ISBN 1-85043-764-5, retrieved 2008-04-30

- Trapp, J. B. (1984). “The Grave of Vergil”. Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes. 47: 1–31. doi:10.2307/751436. JSTOR 751436. S2CID 195009111.

- Ziolkowski, Jan M.; Putnam, Michael C. J. (2008). The Virgilian Tradition: The First Fifteen Hundred Years. Yale University Press. pp. xxxiv–xxxv. ISBN 978-0300108224. Retrieved November 11, 2013.

- Suetonius: The Life of Virgil

- Oggetto Artistico : Virgil’s Tomb Archived 2012-04-02 at the Wayback Machine Parco della Tomba di Virgilio. Circuito informativo regionale della Campania per i Beni Culturali e Paesaggistici.

- Vincenzo Palazzolo di Gravina (1875). Il blasone in Sicilia (in Italian). Visconti & Huber.

- F. Mugnos (2007). Teatro genologico delle famiglie del Regno di Sicilia, rist. an (in Italian). Vol. III. Sala Bolognese: Forni. The Leopardi were descendant of Leopardo, son of Crispo, eldest son of Constantine the Great.

- A. Vitello (1963). I Gattopardi di Donnafugata (in Italian). Flaccovio. p. 39.

External links

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Crypta Neapolitana.

| Archaeological sites in Campania |

|---|

Leave a Reply