Here is another that may make your skin crawl and your blood run cold! Welcome to the world of Gu, the sinister sorcery that turns creepy crawlies into catastrophic curses!

Picture, if you dare, a jar teeming with nature’s most venomous vermin – centipedes, snakes, and scorpions, oh my! But this is no petting zoo, my friends. This is the battleground for a magical massacre, where only the most vicious victor survives!

Born in the shadowy corners of ancient China, Gu (蛊) is the ultimate game of survival of the fittest – with a twist that would make even Darwin’s hair stand on end. The last bug standing becomes a living, breathing curse, capable of controlling minds, destroying fortunes, or dealing death with a single bite!

But wait, there’s more! This creepy-crawly curse comes with its own fashion line. Known as jincan (金蠶) or “golden silkworm,” it’s the must-have accessory for any aspiring sorcerer. Just don’t expect to find it in your local boutique – this golden bug is more likely to be found in the depths of Kashmir or the mountains of Sichuan!

From the oracle bones of the Shang Dynasty to the whispered tales of the Tang, Gu has been slithering its way through Chinese history for millennia. It’s a word that’s more versatile than a Swiss Army knife, meaning everything from “abdominal wug poisoning” to “ghost of a decapitated criminal.” Talk about multitasking!

But beware, aspiring sorcerers! This potent pest comes with a price. Fail to feed your ferocious friend, and you might find yourself on the menu! It’s a double-edged sword sharper than a centipede’s mandibles.

So the next time you see a creepy crawler, remember: it might just be someone’s curse in the making. And if you happen to stumble upon a golden caterpillar at a yard sale, think twice before bringing it home. It might just be a Gu in disguise, ready to make you filthy rich… or filthy dead!

Sleep tight, and don’t let the Gu bite!

Other Notes

Gu (Chinese: 蛊) or jincan (Chinese: 金蠶) was a venom-based poison associated with cultures of south China, particularly Nanyue. The traditional preparation of gu poison involved sealing several venomous creatures (e.g., centipede, snake, scorpion) inside a closed container, where they devoured one another and allegedly concentrated their toxins into a single survivor, whose body would be fed upon by larvae until consumed. The last surviving larva held the complex poison. Gu was used in black magic practices such as manipulating sexual partners, creating malignant diseases, and causing death. According to Chinese folklore, a gu spirit could transform into various animals, typically a worm, caterpillar, snake, frog, dog, or pig.

Names

Circa 14th-century BCE Shang Dynasty oracle inscriptions recorded the name gu, while 7th-century CE Tang Dynasty texts first used jincan “gold silkworm”.

Gu

The term gu 蠱, says Loewe, “can be traced from the oracle bones until modern times, and has acquired a large number of meanings or connotations”.[1]

Before discussing gu, it is necessary to introduce the related word chong 蟲 “wug”.

Chong 蟲 or 虫 (originally a “snake; worm” pictogram) “insect; bug; pest; worm; spider; amphibian; reptile; dragon; etc.” denotes a Chinese folk taxonomy lacking an adequate English translation equivalent. Carr proposes translating chong as “wug“[2] – Brown’s portmanteau word (from worm + bug) bridging the lexical gap for the linguistically widespread “class of miscellaneous animals including insects, spiders, and small reptiles and amphibians”.[3] Contrast the Wug test for investigating language acquisition of plurals in English morphology. Note that “wug” will translate chong below.

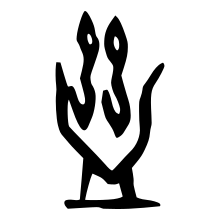

The Traditional Chinese character 蠱 and the Simplified 蛊 for gu “demonic poison” are “wugs inside a container” ideograms that combine chong 蟲 or 虫 “wug” and min 皿 “jar; cup; dish; utensil”. Early written forms of gu 蠱 range from (c. 14th–11th centuries BCE) Oracle bone script to (c. 3rd century BCE) Seal script characters. The Oracle characters had two or one 虫 “wug” elements inside a container, while the Seal characters had three. Shima’s concordance of oracle bone inscriptions lists 23 occurrences of gu written with two wugs and 4 with one; many contexts are divinations about sickness.[4] Marshall concludes, “The oracle-bone character of gu is used to refer to the evil power of the ancestors to cause illness in the living.”[5]

Jincan

Jincan 金蠶 “gold silkworm/caterpillar” is a gu synonym first recorded in the Tang Dynasty. Li Xian‘s (7th century) commentary to the Hou Han Shu uses jincan as the name of a funerary decoration cast from gold, and the (9th century) author Su E 蘇鶚 describes it as a legendary golden-color caterpillar from Kashmir.

Eberhard[6] (cf. 153) connects gu, jincan, and other love charms with the Duanwu Festival that occurs on the fifth day of the fifth month in the Chinese calendar, which is “the theoretical apogee of summer heat”.[7]

Among the Miao on the fifth of the fifth month poisonous animals were put into a pot and allowed to devour each other, and they were called ‘gold-silkworms’. The more people were killed by the ku, the richer the kus owner became. In our time the normal term for ku has been ‘gold-silkworm’. These animals can make gold. It was typical for the gold-silkworm that people continued to feed this animal in the pot, that humans had to be sacrificed to it, that the animal kept the house clean and worked for its master like a brownie, but that it caused harm to its master if he did not provide proper sacrifices.

“For centuries, the Miao, particularly Miao women,” writes Schein, “have been feared for their mastery of the so-called gu poison, which is said to inflict death from a distance with excruciating slowness.”[8]

Groot quotes a Song Dynasty description.

a gold caterpillar is a caterpillar with a gold colour, which is fed with silk from Shuh (Szĕ-ch‘wen). Its ordure, put in food or drink, poisons those who take it, causing certain death. It can draw towards a man the possessions of such victims, and thus make him enormously rich. It is extremely difficult to get rid of it, for even water, fire, weapons or swords can do it no harm. Usually the owner for this purpose puts some gold or silver into a basket, places the caterpillar also therein, and throws the basket away in a corner of the street, where someone may pick it up and take it with him. He is then said to have given his gold caterpillar in marriage.[9]

The Bencao Gangmu[10] quotes Cai Dao 蔡絛’s (12th century) Tieweishan congtan 鐵圍山叢談 that “gold caterpillars first existed” in the Shu region (present-day Sichuan), and “only in recent times did they find their way into” Hubei, Hunan, Fujian, Guangdong, and Guanxi, Hsinchu. Groot also quotes the Tang Dynasty pharmacologist Chen Cangqi (713–741 CE) that:

ashes of old flowered silk are a cure for poison of ku of insects or reptiles which eat such silk. His commentator adds, that those insects are coiled up like a finger-ring, and eat old red silk and flowered silk, just as caterpillars eat leaves; hence, considered in the light of the present day, those insects are gold caterpillars.[11]

Gu meanings

The Hanyu Da Zidian dictionary defines 9 gu 蠱 meanings, plus the rare reading ye 蠱 “bewitchingly pretty; seductive; coquettish” [妖艷].

- (1) Poisoning from an abdominal wug [腹內中蟲食之毒]

- (2) In ancient books, a type of artificially cultured poisonous wug [古籍中一種人工培養的毒蟲]

- (3) Ghost of a person [convicted of gu-magic] whose severed head was impaled on a stake [臬磔死之鬼]

- (4) Evil heat and noxious qi that harms humans [傷害人的熱毒惡氣]

- (5) Wug pest that eats grain. [蛀蟲]

- (6) Sorcery that harms humans [害人的邪術]

- (7) Seduce; tempt; confuse; mislead [蠱惑, 誘惑, 迷惑]

- (8) Affair; assignment [事]

- (9) One of the 64 hexagrams. It is formed from [the trigrams] Gen 艮 [☶ Mountain]) over Xun 巽 [☴ Wind) [六十四卦之一. 卦形为…艮上巽下]

The (early 4th century BCE) Zuozhuan commentary to the (c. 6th–5th centuries BCE) Chunqiu history provides an ancient example of 蠱’s polysemy. It records four gu meanings – 2.5 “grain which (molders and) flies away”, 2.6 “insanity”, 2.7 “delusion and disorder”, and 2.9 “same [hexagram] name” – in a 541 BCE story (昭公1[12]) about a physician named He 和 “Harmony” from Qin explaining gu to the ruler of Jin.

The marquis of [Jin] asked the help of a physician from [Qin], and the earl sent one [He] to see him, who said, “The disease cannot be cured, according to the saying that when women are approached, the chamber disease becomes like insanity. It is not caused by Spirits nor by food; it is that delusion which has destroyed the mind. Your good minister will [also] die; it is not the will of Heaven to preserve him.” The marquis said, “May women (then) not be approached?” The physician replied, “Intercourse with them must be regulated.” … [Zhao Meng] (further) asked what he meant by ‘insanity’; and (the physician) replied, “I mean that which is produced by the delusion and disorder of excessive sensual indulgence. Look at the character; – it is formed by the characters for a vessel and for insects (蠱 = 皿 and 蟲). It is also used of grain which (molders and) flies away. In the [Yijing], (the symbols of) a woman deluding a young man, (of) wind throwing down (the trees of) a mountain, go by the same name (蠱; ☶ under ☴): all these point to the same signification.” [Zhao Meng] pronounced him a good physician, gave him large gifts, and sent him back to [Qin].

Abdominal wug poisoning

The “poisoning from abdominal wugs” or “abdominal parasites” meaning 2.1 first appears in the (121 CE) Shuowen Jiezi dictionary, cf. 2.3 below. It defines gu 蠱 as 腹中蟲也, literally “stomach middle wug”[13] “insects within the stomach”. However, Duan Yucai‘s (1815 CE) commentary construes this definition as “afflicted by abdominal wugs”; and explains that instead of the usual readings zhōng 中 “middle; center; interior” and chóng 蟲 “wug”, both terms should be read in entering tone, namely zhòng 中 “hit (a target); be hit by” and zhòng 蟲 “wug bites”.

Cultivated poisonous wug

The second gu meaning “anciently recorded type of artificially cultured poisonous wug” names the survivor of several venomous creatures enclosed in a container, and transformed into a type of demon or spirit.

The Zhouli ritual text (秋官司寇[14]) describes a Shushi 庶氏 official who, “was charged with the duty of exterminating poisonous ku, attacking this with spells and thus exorcising it, as also with the duty of attacking it with efficacious herbs; all persons able to fight ku he was to employ according to their capacities.” Zheng Xuan‘s commentary explains dugu 毒蠱 “poisonous gu” as “wugs that cause sickness in people”.

Dismembered sorcerer’s ghost

Gu meaning 2.3 “ghost of a person whose severed head was impaled on a stake” refers to the severe Han Dynasty “dismemberment (as tortuous capital punishment)” for criminals convicted of practicing gu-sorcery (see 2.6). Groot[15] “Plate VI, Punishment of Cutting Asunder” provides a gruesome illustration. The Zhouli commentary of Zheng Xuan (cf. 2.2)[16] notes, “Those who dare to poison people with ku or teach others to do it will be publicly executed”.

Eberhard says gu, “was also the soul of a dead person whose head had been pitted on a pole.[17] This, too, fits later reports, in so far as the souls of ku victims often are mentioned as servants of the master of ku, if not ku itself served the master.”

The Shuowen Jiezi (cf. 2.1 above)[16] also defines gu as “the spirits of convicted criminals whose heads had been exposed on stakes.” This specialized torture term niejie 臬磔 combines nie “target” (which pictures a person’s 自 “nose” on a 木 “tree; wooden stand”) and jie 磔 “dismemberment”. Compare the character for xian 縣 “county; district” that originated as a “place where dismembered criminals were publicly displayed” pictograph of an upside-down 首 “head” hanging on a 系 “rope” tied to a 木 “tree”.

Groot suggests this meaning of gu, “seems to reveal to us a belief that such a soul, roaming restlessly about because of its corpse being mutilated, must be avenging itself on the living by settling in their intestines in the shape of the same maggots and grubs which gnaw away its decaying head.”[18]

Unschuld provides historical perspective.

As the legal measures of individual dynasties demonstrate, administrative officials viewed ku as a reality, as late as the nineteenth century. The primary host was considered a criminal; a person guilty of the despicable act of preparing and administering ku poison was executed, occasionally with his entire family, in a gruesome manner. In addition to the obvious desire to punish severely criminal practices that could result in the death of the victim, it is possible that Confucian distaste for the accumulation of material goods, and above all for the resulting social mobility, contributed to this attitude. Indeed, the penalties of the use of ku poison appear to have been more severe than those for other forms of murder.[19]

Heat miasma

The fourth meaning of “evil heat and noxious qi that harms humans” refers to allegedly sickness-causing emanations of tropical miasma. “There was also an ancient belief that ku diseases were induced by some sort of noxious mist or exhalation”, writes Schafer, “just as it was also believed that certain airs and winds could generate worms”.[20]

The Shiji (秦本紀[21]) records that in 675 BCE, Duke De 德公 of Qin “suppressed ku at the commencement of the hottest summer-period by means of dogs. According to commentators, these animals were for the purpose butchered and affixed to the four gates of the capital.” The Tang Dynasty commentary of Zhang Shoujie 張守節 explains gu as “hot, poisonous, evil, noxious qi that harms people”. Displaying gu dogs at city gates reflects meaning 2.3 above.

Besides shapeshifting gu spirits usually appearing as wugs, classical texts record other animal forms. The (c. 350 CE) Soushenji “In Search of the Supernatural” Groot says,

In P’o-yang (in the north of the present Kiangsi pr.) one Chao Shen kept canine ku. Once, when he was called on by Ch’en Ch’en, six or seven big yellow dogs rushed out at this man, all at once barking at him. And when my paternal uncle, on coming home, had a meal with Chao Sheu’s wife, he spit blood, and was saved from death in the nick of time by a drink prepared from minced stalks of an orange-tree. Ku contains spectral beings or spectres, which change their spectral shapes into those of beings of various kinds, such as dogs or swine, insects or snakes, their victims thus never being able to know what are their real forms. When they are put into operation against people, those whom they hit or touch all perish. Tsiang Shi, the husband of my wife’s sister, had a hired work-man in employ, who fell sick and passed blood. The physician opined that he was stricken by ku, and secretly, without informing him of it, strewed some jang-ho root under his sleeping-mat. The patient then madly exclaimed: “The ku which devours me is ceasing to spread”; and then he cried: “It vanishes little by little.” The present generations often make use of jang-ho root to conquer ku, and now and then it has a good effect. Some think it is ‘the efficacious herb’, mentioned in the Cheu li.[22]

This ranghe 蘘荷 “myoga ginger” is a renowned antidote to gu poisoning, see below.

The Shanhaijing (山海经)[23] says the meat of a mythical creature on Mount Greenmound prevents miasmic gu poisoning, “There is an animal on this mountain that looks like a fox, but has nine tails. It makes a noise like a baby. It can devour humans. Whoever eats it will not be affected by malign forces.” The commentary of Guo Pu notes this creature’s meat will make a person immune to the effects of supernatural qi.

A Tang Dynasty account of Nanyue people[20] describes gu miasma:

The majority are diseased, and ku forms in their bloated bellies. There is a vulgar tradition of making ku from a concentration of the hundred kinds of crawling creatures, for the purpose of poisoning men. But probably it is the poisonous crawlers of that hot and humid land which produce it – not just the cruel and baleful nature of the householders beyond the mountain passes.

Wug pest

The “wug pest that eats grain” or “grain that transforms into wugs” meaning 2.5 is seen above in the Zuozhuan explanation of gu as “grain which (molders and) flies away”. The (c. 3rd century BCE) Erya dictionary (6/21) defines gu 蠱 as pests in kang 糠 “chaff”, written with the phonetic loan character kang 康 “healthy”. The (c. 543 CE) Yupian dictionary defines gu as “longstanding grain that transforms into flying insects”.

Groot connects this gu “grain pest” meaning with 2.1 “internal parasites” and 2.7 “debauchery”.

Thus the term ku also included the use of philtre-maggots by women desirous of exciting the lusts of men and attracting them into debauchery. And, evidently, ku was also used to destroy crops or food-stores, or, as the learned physician expressed it, to make the corn fly away, perhaps in the form of winged insects born therein; indeed, the character for ku is regularly used in literature to denote devastating grubs and insects, including internal parasites of the human body, which exercise a destructive influence like poison.[21]

Sorcery

Gu meaning 2.6 “sorcery that harms humans” or “cast damaging spells” is exemplified in the Modern Standard Chinese words wugu 巫蠱 (with “shaman”) “sorcery; art of casting spells” and gudu 蠱毒 (with “poison”) “a venomous poison (used in Traditional Chinese medicine); enchant and injure; cast a harmful spell over”.

Gu-sorcery allegedly resulted in a debilitating psychological condition, often involving hallucinations. The Zuozhuan (宣公8)[24] records that in 601 BCE, Xu Ke 胥克 of Jin was discharged from office because he had gu, “an illness which unsettled his mind”. The Qing Dynasty philologist Yu Yue 俞樾 etymologically connects this meaning of gu 蠱 with gu 痼 “chronic, protracted (illness)”. Guji 蠱疾 “insanity; derangement; condition caused by excessive sexual activities” is a comparable word.

The Hanshu provides details of wugu-sorcery scandals and dynastic rivalries in the court of Emperor Wu (r. 141–87 BCE), which Schafer calls “notorious dramas of love and death”.[25]

This early Chinese history[26] records that in 130 BCE, a daughter of Empress Chen Jiao (who was unable to bear a son) was accused of practicing wugu and maigu 埋蠱 “bury a witchcraft charm [under a victim’s path or dwelling]” (cf. voodoo doll). The “empress was dismissed from her position and a total of 300 persons who were involved in the case were executed”; specifically[18] “their heads were all exposed on stakes” (cf. 2.3). This history claims wu 巫 “shamans” from Yue conducted the gu magic, which Eberhard notes, “seems to have consisted, at least in part, of magic human figures buried under the road which the emperor, the intended victim, was supposed to take”.[17]

Accusations of practicing wugu-magic were central to the 91 BCE (Wugu zhi huo 巫蠱之禍) attempted coup against crown prince Liu Ju by Jiang Chong 江充 and Su Wen 蘇文. The Hanshu[27] claims that, “no less than nine long months of bloody terrorism, ending in a tremendous slaughter, cost some tens of thousands their lives!”

Traditional Chinese law strictly prohibited practicing gu-sorcery. For instance, during the reign of Tang Empress Wu Zetian, Schafer says,

the possession of ku poison, like the casting of horoscopes, was cause for official suspicion and action: At that time many tyrannical office holders would orders robbers to bury ku or to leave prophecies in a man’s household by night. Then, after the passage of a month, they would secretly confiscate it.[25]

Seduce

This gu meaning 2.7 of “seduce; bewitch; attract; confuse; mislead; bewilder” is evident in the Standard Chinese words yaogu 妖蠱 “bewitch by seductive charms”, gumei 蠱媚 “bewitch/charm by sensual appeal”, and guhuo 蠱惑 “confuse by magic; enchant; seduce into wrongdoing”. “Ku-poisoning was also associated with demoniac sexual appetite – an idea traceable back to Chou times”, says Schafer, “This notion evidently had its origins in stories of ambiguous love potions prepared by the aboriginal women of the south”.[25]

The Zuozhuan (莊公28)[28] uses gu in a story that in the 7th century BCE, Ziyuan 子元, the chief minister of Chu, “wished to seduce the widow” of his brother King Wen of Zhou. The Mozi (非儒下)[29] uses gu to criticize Confucius, who “dresses elaborately and puts on adornments to mislead the people.” The Erya (1B/49, cf. 2.5 above) defines gu 蠱, chan 諂 “doubt; flatter”, and er 貳 “double-hearted; doubtful” as yi 疑 “doubt; suspect; fear; hesitate”. Guo Pu‘s commentary suggests this refers to gu meaning “deceive; seduce”.

Many later accounts specify women as gu-magic practitioners. Eberhard explains,

We know that among many aborigines of the south women know how to prepare love charms which were effective even at a distance. In these reports it was almost invariably stated that the love charm had a fatal effect if the man, to whom the charm was directed, did not return to the woman at a specified time.[30]

Affair

The least-attested gu 蠱 meaning 2.8 of “affair; event” first appears in the (3rd century CE) Guangya dictionary, which defines gu as shi 事 “assignment; affair; event; thing; matter; trouble”.

The Yijing Gu hexagram (see 2.9) “Line Variations” repeatedly refer to parental gu with the enigmatic phrases 幹父之蠱 “gan-father’s gu” and 幹母之蠱 “gan-mother’s gu“. Wang Niansun quotes an Yijing commentary that gu means shi, and proposes gu 蠱 is a phonetic loan character for gu 故 “reason; cause; event; incident”. Commentarial tradition takes gan 幹 “trunk; framework; do; work” to mean chi 飭 “put in order”, and Richard Wilhelm translates “Setting right what has been spoiled by the father” and “Setting right what has been spoiled by the mother”.[31] Arthur Waley follows an ancient interpretation that gan 幹 is a variant Chinese character for gan 干 “stem; Celestial stem; day of the (10-day) week; involve”, translating “stem-father’s maggots” and “stem-mother’s maggots”, explaining

it is surely obvious that the maggots referred to are those which appeared in the flesh of animals sacrificed to the spirits of dead parents, who after their death were, for reasons of taboo, only known by the name of the day upon which they were born, being merely a fuller way of writing ‘stem’, ‘day of the week’.[32]

Hexagram 18

Gu 蠱 names the Yì-Jīng Hexagram 18, which is translated as “Destruction” (Z.D. Sung 1935), “Work on What Has Been Spoiled [Decay]”,[33] “Decay” (John Blofeld 1965), “Degeneration” (Thomas Cleary 1986), “Poison, Destruction” (Wu Jing-Nuan 1991), and “Ills to Be Cured” (Richard John Lynn 1994). Wilhelm explains translating “decay” for 蠱.[31]

The Chinese character ku represents a bowl in whose contents worms are breeding. This means decay. It has come about because the gentle indifference in the lower trigram has come together with the rigid inertia of the upper, and the result is stagnation. Since this implies guilt, the conditions embody a demand for removal of the cause. Hence the meaning of the hexagram is not simply “what has been spoiled” but “work on what has been spoiled.”

“The Judgment”:[31] “WORK ON WHAT HAS BEEN SPOILED Has supreme success. It furthers one to cross the great water. Before the starting point, three days. After the starting point, three days.” “The Image”[34] reads: “The wind blows low on the mountain: The image of DECAY. Thus the superior man stirs up the people, And strengthens their spirit.”

In the Zuozhuan (僖公15),[35] divination of this Gu hexagram foretells Qin conquering Jin, “A lucky response; cross the Ho; the prince’s chariots are defeated.”

Gu techniques

According to ancient gu traditions, explain Joseph Needham and Wang Ling, “the poison was prepared by placing many toxic insects in a closed vessel and allowing them to remain there until one had eaten all the rest – the toxin was then extracted from the survivor.”[36] They note, “It is strange to think that this same method has been successfully employed in our own times for the isolation of strains of soil bacteria capable of attacking the tuberculosis bacillus”.

Feng and Shryock describe contemporary practices of gu.

At present, ku is used primarily as a means of acquiring wealth; secondarily as a means of revenge. The method is to place poisonous snakes and insects together in a vessel until there is but one survivor, which is called the ku. The poison secured from this ku is administered to the victim, who becomes sick and dies. The ideas associated with ku vary, but the ku is generally regarded as a spirit, which secures the wealth of the victim for the sorcerer.[37]

Eberhard summarizes gu practices.

The essence of ku, then, was the magic charm that could be prepared out of the surviving animal in the pot. It could be used as a love charm with the object of forcing the loved male to come back to the woman. The ku could be used also as an evil magic with the object of obtaining subservient spirits. This was done by feeding it to unrelated persons who would either spit blood or whose stomachs would swell because of the food they had taken would become alive in their insides, and who would die as a result; similar to the gold-silkworms, their souls had to be servants of the owner of the ku.[17]

The 4th-century Soushenji (cf. 2.4)[38] records that gu breeding was a profitable but dangerous profession in the Henan region.

In the province of Yung-yang, there was a family by the name of Liao. For several generations they manufactured ku, becoming rich from it. Later one of the family married, but they kept the secret from the bride. On one occasion, everyone went out except the bride, who was left in charge of the house. Suddenly she noticed a large cauldron in the house, and on opening it, perceived a big snake inside. She poured boiling water into the cauldron and killed the snake. When the rest of the family returned she told them what she had done, to their great alarm. Not long after, the entire family died of the plague.

Feng and Shryock describe how 20th-century Zhuang women in Guangxi elaborately produced gu during the Duanwu Festival (see jincan above).[39]

Ku poison is not found generally among the people (i.e., the Chinese), but is used by the T’ung women. It is said that on the fifth day of the fifth month, they go to a mountain stream and spread new clothes and headgear on the ground, with a bowl of water beside them. The women dance and sing naked, inviting a visit from the King of Medicine (a tutelary spirit). They wait until snakes, lizards, and poisonous insects come to bathe in the bowl. They pour the water out in a shadowy, dark place. Then they gather the fungus which grows there, which they make into a paste. They put this into goose-feather tubes and hide them in their hair. The heat of their bodies causes worms to generate, which resemble newly-hatched silk-worms. Thus ku is produced. It is often concealed in a warm, dark place in the kitchen. The newly made ku is not yet poisonous. It is used as a love potion, administered in food and drink and called “love-medicine.” Gradually the ku becomes poisonous. As the poison develops, the woman’s body itches until she has poisoned someone. If there is no other opportunity, she will poison even her husband or her sons. But she possesses antidotes. It is believed that those who produce ku themselves become ku after death. The ghosts of those who have died from the poison become their servants.

Gu remedies

Groot and Eberhard detail numerous Chinese antidotes and cures for gu poison-magic.[40] For instance (see 2.4), the Shanhaijing claimed eating a legendary creature’s meat would prevent gu and the Soushenji prescribed ranghe 蘘荷 “myoga ginger”. Unschuld says

Prescription literature was filled with antidotes. All known Chinese conceptual systems of healing dealt with the ku phenomenon and developed therapeutic strategies that were in accord with their basic principles. The Buddhists recommended prayers and conjurations, thus utilizing the same methods as practitioners of demonic medicine. In pharmaceutical literature, drugs of a plant, animal, or mineral origin were described as effective against ku poisoning. Adherents of homeopathic magic recommended the taking of centipedes, since it was known that centipedes consume worms.[41]

The Zhou houbei jifang 肘後備急方,[42] which is attributed to Ge Hong, describes gu diagnosis and cure with ranghe:

A patient hurt by ku gets cutting pains at his heart and belly as if some living thing is gnawing there; sometimes he has a discharge of blood through the mouth or the anus. If he is not forthwith medically treated, it devours his five viscera, which entails his death. To discover whether it is ku or not, let the patient spit into water; if the spittle sinks, it is ku; if it floats, it is not. The recipe for discovering the name of the owner of the ku poison is as follows: take the skin of a drum, burn it, a small piece at a time, pulverize the ashes, and let the patient drink them with water; he will then forthwith mention the name; then bid this owner forthwith to remove the ku, and the patient will recover immediately. Again place some jang-ho leaves secretly under the mattress of the patient; he will then of his own accord immediately mention the name of the owner of the ku

Many gu-poison antidotes are homeopathic, in Western terms. The 8th-century pharmacologist Chen Cangqi[43] explains using venomous creatures both to produce and cure gu-poison.

In general reptiles and insects, which are used to make ku, are cures for ku; therefore, if we know what ku is at work, we may remedy its effects. Against ku of snakes that of centipedes should be used, against ku of centipedes that of frogs, against ku of frogs that of snakes, and so on. Those varieties of ku, having the power of subduing each other, may also have a curative effect .

Needham and Wang say prescribing gu poison as a cure or preventive suggests “that someone had stumbled on an immunisation process”, and suggest scorpion-venom and centipede-venom as possible toxins.[36]

Chen[44] further describes catching and preparing medicine from the shapeshifting gu creature that,

… can conceal its form, and seem to be a ghost or spirit, and make misfortune for men. But after all it is only a reptile ghost. If one of them has bitten a person to death, it will sometimes emerge from one of that man’s apertures. Watch and wait to catch it and dry it in the warmth of the sun; then, when someone is afflicted by the ku, burn it to ashes and give him a dose of it. Being akin, to it, the one quite naturally subdues the other.

Besides such homeopathic remedies, Schafer says one could,

give ku derived from particularly venomous creatures to overcome that taken from less lethal creatures. Thus centipede ku could be overcome by frog ku; serpent ku would prevail over frog ku, and so on. There were also soberer, though almost as powerful remedies: asafetida, python bile, civet, and a white substance taken from cock’s dung were all used. It is not certain what real maladies these repellent drugs, cured, or seemed to cure. Probably they ranged from the psychosomatic to the virus-born. Many oedematous conditions were called ku, and it has been plausibly suggested that some cases were caused by intestinal parasites (hence the constant worm motif). Others are attributable to fish poisons and arrow poisons concocted by the forest dwellers.[25]

Chinese folklore claims the definitive cure for gu-magic is passing it on to a greedy person. Eberhard says,

The most common way to get rid of the ku (just as of brownies and the golden-silkworm) was to give it away as a present. The actions of a man in Chang-chou (Fukien) are rather uncommon. He found on the ground a package containing three large silver bars wrapped in silk and in addition a ku which looked like a frog (ha-ma); in spite of the danger he took it; at night two large frogs appeared which he cooked and ate; on the next night more than ten smaller frogs appeared which he also ate up; and he continued consuming all frogs that kept appearing until the magic was cast off; in this fashion the man suffered no ill effects from the ku poison.[45]

From descriptions of gu poisoning such involving “swollen abdomen, emaciation, and the presence of worms in the body orifices of the dead or living”, Unschuld reasons, “Such symptoms allow a great number of possible explanations and interpretations”.[46] He suggests attitudes toward gu were based upon fear of others, envy, and greed. “But the concept of ku is unknown outside of China. Instead, one finds what may be its conceptual equivalent, the ‘evil eye’, present in all ‘envy societies’.”

See also

References

- Groot, Jan Jakob Maria (1910). The Religious System of China: Its Ancient Forms, Evolution, History and Present Aspect, Manners, Customs and Social Institutions Connected Therewith. (6 volumes). Brill.

- Eberhard, Wolfram (1968). The Local Cultures of South and East China. E.J. Brill.

- Feng, H. Y.; Shryock, J. K. (1935). “The Black Magic in China Known as Ku“. Journal of the American Oriental Society. 553 (1): 1–30. doi:10.2307/594297. JSTOR 594297.

- The Chinese Classics, Vol. V, The Ch’un Ts’ew with the Tso Chuen. Translated by Legge, James. Oxford University Press. 1872.

- Loewe, Michael (1970). “The Case of Witchcraft in 91 B.C.: Its Historical Setting and Effect on Han Dynastic History”. Asia Major. 153 (2): 159–196.

- Schafer, Edward H. (1967). The Vermillion Bird: T’ang Images of the South. University of California Press.

- Unschuld, Paul U. (1985). Medicine in China: A History of Ideas. University of California Press.

- Wilhelm, Richard; Baynes, Cary F. (1967). The I Ching or Book of Changes. Bollingen series XIX. Princeton University Press.

Footnotes

- Loewe 1970, p. 191.

- Carr, Michael (1983). “Why Did 蟲 *D’iông Change from ‘Animal’ to ‘Wug’?”. Computational Analyses of Asian & African Languages. 21: 7–13. p. 7.

- Brown, Cecil. H. (1979). “Folk Zoological Life-Forms: Their Universality and Growth”. American Anthropologist. 813 (4): 791–812. doi:10.1525/aa.1979.81.4.02a00030.

- Shima, Kunio 島邦夫 (1958). Inkyo bokuji sōrui 殷墟卜辞綜類 (in Japanese). Hirosaki. p. 386.

- Marshall, S. J. (2001). The Mandate of Heaven. Columbia University Press. p. 129.

- Eberhard 1968, p. 149–50.

- Groot 1910, vol. 5, p. 851.

- Schein, Louisa (2000). Minority Rules: The Miao and the Feminine in China’s Cultural Politics. Duke University Press. pp. 50–1.

- Groot 1910, vol. 5, p. 854.

- Groot 1910, vol. 5, p. 850-851.

- Groot 1910, vol. 5, p. 853-854.

- Legge 1872, pp. 580–1.

- Loewe 1970, p. 192.

- Groot 1910, vol. 5, p. 826.

- Groot 1910, vol. 5, p. 840.

- Loewe 1970, p. 195.

- Eberhard 1968, p. 152.

- Groot 1910, vol. 5, p. 828.

- Unschuld 1985, pp. 49–50.

- Schafer 1967, p. 102.

- Groot 1910, vol. 5, p. 827.

- Groot 1910, vol. 5, pp. 846-7.

- The Classic of Mountains and Seas. Translated by Birrell, Anne. Penguin. 2000. p. 4.

- Legge 1872, p. 302.

- Schafer 1967, p. 103.

- Loewe 1970, p. 169.

- Groot 1910, vol. 5, p. 836.

- Legge 1872, p. 115.

- The Ethical and Political Works of Motse. Translated by Mei, Yi-Pao. Arthur Probsthain. 1929.

- Eberhard 1968, p. 149.

- Wilhelm & Baynes 1967, p. 75.

- Waley, Arthur (1933). “The Book of Changes”. Bulletin of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities. 5: 121–142. p. 132.

- Wilhelm & Baynes 1967.

- Wilhelm & Baynes 1967, p. 76.

- Legge 1872, p. 167.

- Needham, Joseph; Wang, Ling (1956). Science and Civilization in China. Volume 2. History of Scientific Thought. Cambridge University Press. p. 136. ISBN 9780521058001.

- Feng & Shryock 1935, p. 1.

- Feng & Shryock 1935, p. 7.

- Feng & Shryock 1935, pp. 11–2.

- Groot 1910, vol. 5, pp. 861-9; Eberhard 1968, pp. 152–3.

- Unschuld 1985, p. 47.

- Groot 1910, vol. 5, p. 862.

- Groot 1910, vol. 5, p. 866.

- Schafer 1967, p. 102, cf. Groot 1910, vol. 5, p. 847

- Eberhard 1968, p. 153.

- Unschuld 1985, p. 48.

Further reading

- Obringer, Frédéric, “L’Aconit et l’orpiment. Drogues et poisons en Chine ancienne et médiévale”, Paris, Fayard, 1997, pp. 225-273.

Leave a Reply