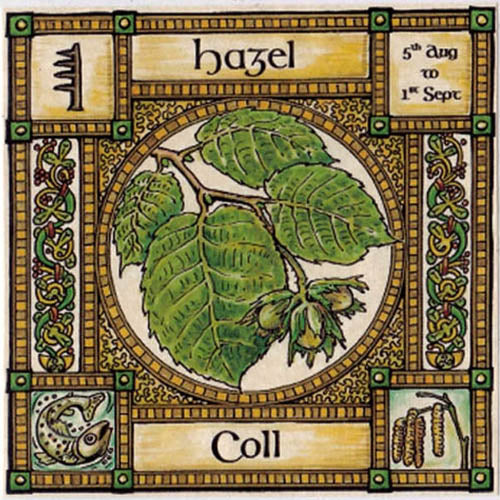

hazel

Hazels are plants of the genus Corylus of deciduous trees and large shrubs native to the temperate Northern Hemisphere. The genus is usually placed in the birch family Betulaceae, though some botanists split the hazels (with the hornbeams and allied genera) into a separate family Corylaceae. The fruit of the hazel is the hazelnut. Archaeologists found large quantities of hazelnut shells in Mesolithic and Neolithic sites in what is now Sweden, Denmark, and Germany. Evidence of hazelnuts in China dates to around 3000 B.C.

The oldest confirmed hazel species is Corylus johnsonii found as fossils in the Ypresian-age rocks of Ferry County, Washington, USA

Botanical name

corylus

from Greek

Korys 'hat or helmet'

Never forget to scroll down! Never forget to scroll down! Never forget to scroll down!

“If you you love me, crack and fly; If you hate me, burn and die.”

Two hazel-nuts I threw into the flame,

And to each nut I gave a sweetheart’s name:

This with the loudest bounce me sore amazed,

That in a flame of brightest colour blazed;

As blazed the nut, so may thy passion grow,

For ’twas thy nut that did so brightly glow!

Burning the nuts is a favourite charm.

They name the lad and lass to each particular nut, as they lay them in the fire;

and accordingly as they burn quietly together, or start from beside one another,

the course and issue of the courtship will be.”

water witching

hazel rods were all the rage

What On Earth

Penitential

Rods

I stumbled upon this as one of those red links to nowhere on Wikipedia (where it was called Virgula Poenitentiaria - penitential wand in Rome).

I immediately consulted Google but Google is not cooperating. I find it hard to believe two blogs and a reddit article is the totality of the information available. Either the search criteria is incorrect or this material is missing/sparce from the internet. This may not be its final resting place but it looks interesting and I want to make a note of it.

the penitential rod

Nevertheless, one website says:

"In the great Roman Major Basilicas there were special indulgences granted to pilgrims on certain days of the year and special occasions. You would approach the Major (or Minor) Penitentiary, seated on his great throne-like chair (for he was like a tribune or judge), kneel before him and – if you had a document saying that you had fulfilled your pilgrimage, etc., it would be brought to him – he would then bop you on your penitential head with the penitential wand in his benignity, thus granting you the indulgence. There is still one of these chairs in St. John Lateran."

One website says:

"In the great Roman Major Basilicas there were special indulgences granted to pilgrims on certain days of the year and special occasions. You would approach the Major (or Minor) Penitentiary, seated on his great throne-like chair (for he was like a tribune or judge), kneel before him and – if you had a document saying that you had fulfilled your pilgrimage, etc., it would be brought to him – he would then bop you on your penitential head with the penitential wand in his benignity, thus granting you the indulgence. There is still one of these chairs in St. John Lateran."

And I found this on Reddit (the author attributes 'the last page of the 1952 editio typica of the Enchiridion Indulgentiarum'):

THE PENITENTIAL ROD 781

To the faithful, who on any day of the year, in the Basilicas of St John Lateran, St Peter, St Paul Outside the Walls, and St Mary Major, shall go to the Minor Penitentiaries, and submit themselves, moved by feelings of Christian humility and sincere contrition, to be touched with the penitential rod, is granted:

An indulgence of three hundred days, once per day.

But to those who shall go to His Eminence the Cardinal Major Penitentiary, exercising his office on the appointed days of Holy Week in the four said Basilicas, and who, moved by the same feelings, equally submit themselves to be touched with the penitential rod, is granted:

An indulgence of seven years (S. Paen. Ap., 20 Jul., 1942).

and in the same Reddit article, this is said to be from p. 239 of Acta Apostolicae Sedis 34

The penitential rod This custom of the penitential rod—which had become largely symbolic, because for a good long while it had not been a matter of a good beating (even deserved) of repentant penitents—consisted in letting one's head or shoulder be touched by the very long stick which the Penitentiary bore on certain days of Holy Week.

I am putting the verbs in the past tense, because it is no use anymore to hurry to the Roman basilicas for this motive (nor others besides): the custom has lapsed into desuetude, not to say been abrogated (but abrogated is a legal term ) since 1967 (if memory serves) for reasons that are easy to guess and which I need not explain here.

I personally had the privilege of getting to know and admire two minor penitentiaries (one formerly of St Peter's Basilica, the other of St Mary Major), in the early 1980s, who had never given in to the Novus Ordo Missae and had hidden themselves during these years of lead among friends to celebrate in private oratories (and more without naming the pope in the Canon). But they never applied the penitential rod, however much I asked. And they both departed this vale of tears some years ago.

and this, said to be written by a Jesuit in 1665:

"This custom of the penitential rod—which had become largely symbolic, because for a good long while it had not been a matter of a good beating (even deserved) of repentant penitents—consisted in letting one's head or shoulder be touched by the very long stick which the Penitentiary bore on certain days of Holy Week. the custom was abolished in 1967.

TWO

SHAKES

of A

LAMB'S TAIL

Hazel catkins or lambs' tails

These familiar yellow tassels are the male flowers that release their powdery pollen as they dance on the breeze, while the inconspicuous female flowers on the same twigs, wait for it to blow their way. Hazel Catkins If you still need convincing that the Spring is well under way look out for the splashes of golden catkins unfurling from Hazel trees. They flower at a time when there aren’t many insects around to do the job and are finished before the leaves start to grow. These male catkins began forming in the Autumn and have passed the winter months as little hard buds, each holding about one hundred flowers. As the daylight increases, they slowly open out into long, dangly ‘lambs’ tails’ shedding clouds of yellow pollen onto each breath of wind. "To avoid self-fertilisation, each Hazel tree waits until its male catkins have died before opening the almost invisible female flowers. These are really hard to see, consisting of tiny tufts of red hairs peeking out from a round bud which will become the familiar hazelnut if fertilized. You’ll find catkins on other trees that are pollinated by the wind e.g. hazel, birch, oak and beech trees as well.

"If you give the branch a shake, a million tiny particles of golden dust will flood out as if by magic – a truly breathtaking sign that Spring has begun."

Young male catkins of hazel (Corylus avellana)

Etymology of catkin illustrated by pussy willow catkins from a children's book

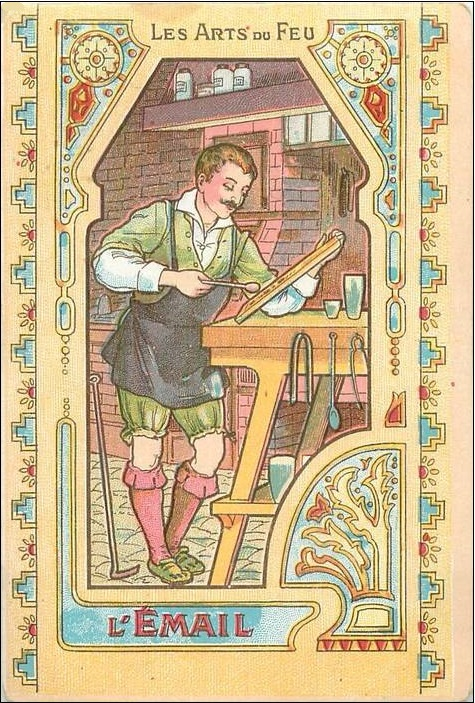

ANCIENT ENAMEL RECIPE CALLS FOR OIL OF FILBERTS AND HAZEL ROD

“Enamel is thus made : take lead, and melt it, continually taking off the pellicle which floats on the surface, until the whole of the lead is wasted away; of which take one part, and of the powder hereafter mentioned, as much; and this is the said powder: take small white pebbles which are found in streams, and pound them into most subtle powder; and if you wish to have yellow enamel, add oil of filberts and stir with a hazel rod; for green, add filings of copper, or verdigris; for red, add filings of latten with calamine; for blue, good azure* or saff’re, of which glaziers make blue glass.”

FROM THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL JOURNAL

OF

FILBERTS

AND

PHILBERTS

AND feast days

Hazelnuts, cobnuts and Filberts

The hazelnut is the fruit of the hazel tree and therefore includes any of the nuts deriving from species of the genus Corylus, especially the nuts of the species Corylus avellana. They are also known as cobnuts or filberts according to species.

A hazelnut cob is roughly spherical to oval, about 15–25 millimetres (5⁄8–1 inch) long and 10–15 mm (3⁄8–5⁄8 in) in diameter, with an outer fibrous husk surrounding a smooth shell, while a filbert is more elongated, being about twice as long as its diameter. The nut falls out of the husk when ripe, about seven to eight months after pollination. The seed is edible and consumed raw, roasted or ground into a paste. The seed has a thin, dark brown skin, which is sometimes removed before cooking.

Cobnuts

In Ireland and the United Kingdom, hazelnuts are sometimes referred to as cobnuts, for which a specific cultivated variety – Kent cobnuts – is the main variety cultivated in fields known as plats, hand-picked, and eaten green. According to the BBC, a national collection of cobnut varieties exists at Roughway Farm in Kent.

Corylus maxima, the filbert, is a species of hazel

The filbert is similar to the related common hazel, C. avellana, differing in having the nut more fully enclosed by the tubular involucre. This feature is shared by the beaked hazel C. cornuta of North America, and the Asian beaked hazel C. sieboldiana of eastern Asia.

Filbertone is the principal flavor compount of hazelnuts

It is used in perfumery and is designated as generally recognized as safe (GRAS) for use in foods. Because filbertone is found in hazelnut oil, its presence can be used to detect the adulteration of olive oil with less expensive hazelnut oil. The natural compound is mixture of both enantiomers, and the composition can vary depending on the source. See also: 2-Octanone and 3-Octanone

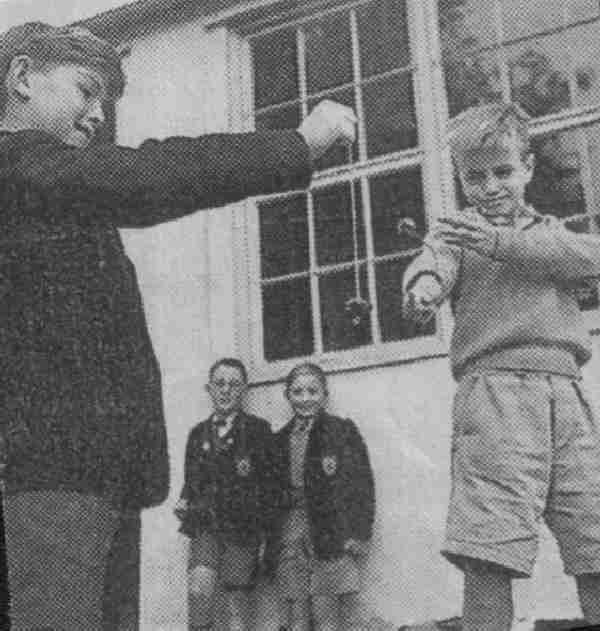

They are called cobnuts because cob was a word used to refer to the head or "noggin", and children had a game in which they would tie a string to a hazelnut and use it to try to hit an opponent on the head.

Statue of Saint Philibert

CONKERS

CHILDREN'S

GAME

THIS GAME IS CURRENTLY PLAYED WITH BUCKEYES

Conkers is a traditional children's game in Great Britain and Ireland played using the seeds of horse chestnut trees—the name 'conker' is also applied to the seed and to the tree itself. The game is played by two players, each with a conker threaded onto a piece of string: they take turns striking each other's conker until one breaks.

The first mention of the game is in Robert Southey's memoirs published in 1821. He describes a similar game, but played with snail shells or hazelnuts. It was only from the 1850s that using horse chestnuts was regularly referred to in certain regions. The game grew in popularity in the 19th century, and spread beyond England. The first recorded game of conkers using horse chestnuts was on the Isle of Wight in 1848

There is uncertainty of the origins of the name. The name may come from the dialect word conker, meaning "knock out" (perhaps related to French conque meaning a conch, as the game was originally played using snail shells and small bits of string.

The name may also be influenced by the verb conquer, as earlier games involving shells and hazelnuts have also been called conquerors.

Another possibility is that it is an onomatopoeia, representing the sound made by a horse chestnut as it hits another hard object, such as a skull (another children's "game", also called conkers, consists of simply throwing the seeds at one another over a fence or wall).

FROM HAZELNUTS TO BUCKEYES

The Hazel Moon was known to the Celts as Coll, which translates to "the life force inside you". Hazel is often associated in Celtic lore with sacred wells and magical springs containing the salmon of knowledge.

Magical History & Associations: The bird associated with this month is the crane, the color is brown, and the gemstone is band-red agate. The Hazel, a masculine herb, is associated with the element of air, the planet of Mercury, the day of Wednesday, and is sacred to Mercury, Thor, Artemis, Fionn, Diana and Lazdona (the Lithuanian Hazelnut Tree Goddess).

This website says:

- In England, all the knowledge of the arts and sciences was thought to be bound to the eating of Hazel nuts.

- Hazel also has protective uses as anti-lightning charms.

- A sprig of Hazel or a talisman of two Hazel twigs tied together with red or gold thread to make a solar cross can be carried as a protective good luck charm.

- The mistletoe that grows on hazel protects against bewitching.

- A cap of Hazel leaves and twigs ensures good luck and safety at sea, and protects against shipwrecks.

- In England, the Hazelnut is a symbol of fertility – a bag of nuts bestowed upon a bride will ensure a fruitful marriage.

- The Hazel is a tree that is sacred to the fey Folk. A wand of hazel can be used to call the Fey.

- If you sleep under a Hazel bush you will have vivid dreams.

- Hazel can be used for all types of divination and dowsing.

- Until the seventeenth century, a forked Hazel stick was used to divine the guilt of persons in cases of murder and theft.

- Druids often made wands from Hazel wood, and used the wands for finding ley lines.

- Hazel twigs or a forked branch can be used to divine for water or to find buried treasure.

- The wood of the Hazel can help to divine the pure source of poetry and wisdom.

and this website says:

- The importance of the well of wisdom can be readily observed at many holy wells and sacred springs around Ireland, where hazel trees grow to this day, and their branches are often decorated with strips of colorful cloth at votive offerings.

- Ancient Gaelic well shafts have been found which revealed gifts to the otherworld wrapped in hazel leaves and nuts.

- The Tuatha Lord whose name was Mac Cuill, or son of the hazel, was given a third of the country for his use to grow hazel trees.

- The seat of the High Kings of Ireland, Tara, was raised close to a hazel wood, and Clonard’s mighty monastery was built in the Wood of the White Hazel.

- Placenames associated with the hazel can be found everywhere in Ireland, and along with the apple tree and the hawthorn, marked the borders between worlds where magical things happened. These trees were said to be guarded by the fairy of poetry, the Bile Ratha, called the Hind Etin in Scotland and by other names in other places.

- The druids brewed a strange liquor called “hazelmead” which gave them prophetic dreams and uncanny visions, especially when consumed before the fires of the cross-quarter festivals, the soltices.

- Besides its rich mythological value, the hazel tree had many practical uses – for the making of staves and walking sticks, with hazel shafts being pinned into the curve of a shepherd’s crook as they grew, for making wattle huts and walls, the frames of coracle boats, baskets and all things of woven wood, to hold down the thatch on cottage roofs, and the leaves were fed to cattle as fodder in winter. One source said the last item ensured milk production. I will link it here when I find it again. In the meantime, I found this recent study suggesting hazel leaves, in place of alfalfa, substantially shifted volatile urinary nitrogen to the faeces and reduced methane emissions without reducing milk production in dairy cows: [M. Terranova, Increasing the proportion of hazel leaves in the diet of dairy cows reduced methane yield and excretion of nitrogen in volatile form, but not milk yield, Animal Feed Science and Technology Volume 276, June 2021 doi.org/10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2020.114790]

- Most importantly, the nuts of the hazel tree were eaten as food, providing much-needed protein which was often ground and added to flour for bread.

- A paste made from hazelnuts was used as a replacement for chocolate at times, and it can be mashed into butter as well.

well of Wisdom

The Celts believed hazelnuts gave wisdom and inspiration. According to Celtic mythology a hazel tree was the first creation on Earth. Some say the first Irish hazel tree grew upon the Well of Wisdom and held all the knowledge of the universe within itself. There are numerous variations of this tale including one where nine hazel trees grew around a sacred pool. In any case, hazelnuts dropped into the water and were eaten by salmon (a sacred fish) which absorbed the wisdom. A Druid teacher, in his bid to become omniscient, caught one of these special salmon and asked a student to cook the fish, but not to eat it. While he was cooking the fish, a blister formed and he used his thumb to burst it, which he then put to his mouth to cool, thereby absorbing the fish's wisdom. This boy was called Fionn Mac Cumhail (Fin McCool) and went on to become one of the most heroic leaders in Gaelic mythology.

Connla's Well

The Dindsenchas of Irish mythology ( meaning "lore of places") give the physical origins, and etymological source of several bodies of water – in these myth poems the sources of rivers and lakes is sometimes given as being from magical wells. Connla's Well is one of a number of wells in the Irish "Celtic Otherworld". It is also termed "The Well of Wisdom", or "The Well of Knowledge", and is the mythical source of the River Shannon. The epithet Connla's Well is known from the Dindsenchas. Another well is described in the dindsenchas about Boann, in the text as ("Secret Well") mythologically given as the origin of the River Boyne. This well has also been referred to as Nechtan's Well, or the Well of Segais. Some writers conflate both Nechtan's and Connla's well, making it the source of both Shannon and Boyne. Loch Garman's mythological origin is also given in the dindsenchas – in some translations or interpretations of the text the source of the water is given as the Well of Coelrind, though this has also been rendered as port of .., or even fountain of ...

Connla's Well In the Dindsenchas (Sinann I) refers to a "well with flow unfailing" as the source of the Sinann (Shannon). In (Sinann II) the well is referred to as Connla's well. In the poem the well is associated with the drowning of Sinend, daughter of Lodan Lucharglan, son of Ler, of the Tuatha Dé Danann – giving the river its name. Hazel trees, the nuts thereof which fall into the water and feed Salmon are also mention in Sinann II.

Tipra Chonnlai, ba mór muirn, | Connla’s well, loud was its sound, |

| (Gwynn 1913, Sinann II, pp.292–293) | |

(Meyer & Nutt 1895) speculated that the name Connla's Well derived from some event (now lost) happening after Connla the Ruddy's journey to the land of the Aos Si. (O'Curry 1883) states that there is a tradition that the seven streams flowing from the well formed the rivers including the River Boyne, River Suir, River Barrow, and River Slaney.

Nechtain mac Labrada laind, | Nechtain son of bold Labraid |

| (Gwynn 1913, Boand I, pp.28–29) | |

Well of Segais/Nechtan's Well

This well is sometimes known as the Well of Segais (Segais means "forest"), from Boann's name in the otherwold, and the Boyne is also known as the Sruth Segsa. Other sources also refer to this well as Nechtan's Well. In the Dictionary of Celtic Mythology (ed. James MacKillop) this well, as well as the Well of Connla are conflated, as Well of Segais, which is stated to be the source of both the River Shannon and River Boyne.

Well of Coelrind

The term Well of Coelrind has been used with reference to the formation of Loch Garman as described in the dindsenchas. In the tale Garman mac Bomma Licce (Garman, son of Bomma Licce) steals the queen's crown at Temair during the drinking during the feast of Samain. He is pursued to the mouth of the River Slaney where the waters burst forth drowning him – hence giving the name of Loch Garman. In (Gwynn 1913) there is no mention of a well, the place is rendered as port Cóelrenna ("port Coelrenna"). In (Stokes 1894) the place of drowning is translated as the "well of Port Coelrenna", and the water is said to have burst forth as Garman was being drowned. Elsewhere the place is translated "fountain [of] Caelrind".

Legacy

Connla's Well is a common motif in Irish poetry, appearing, for example, in George William Russell's poem "The Nuts of Knowledge" or "Connla's Well": And when the sun sets dimmed in eve, and purple fills the air, I think the sacred hazel-tree is dropping berries there, From starry fruitage, waved aloft where Connla's Well o'erflows; For sure, the immortal waters run through every wind that blows. Yeats described the well, which he encountered in a trance, as being full of the "waters of emotion and passion, in which all purified souls are entangled". See also:

Ogham

Ogham is an Early Medieval alphabet sometimes known as the Celtic tree alphabet. Coll is the Irish name of the ninth letter of the Ogham alphabet ᚉ, meaning "hazel-tree", which is related to Welsh collen pl. cyll, and Latin corulus. Its Proto-Indo-European root was *kos(e)lo-. Its phonetic value is [k]. Eamhancholl ᚙ CH or X, later AE means twin-of-coll or twin-of-hazel.

fairy tales

"The Hazelnut Child" (German: Das Haselnusskind) is a Bukovinian fairy tale collected by the Polish-German scholar Heinrich von Wlislocki (1856–1907) in Märchen Und Sagen Der Bukowinaer Und Siebenbûrger Armenier (1891, Hamburg: Verlagsanstalt und Druckerei Actien-Gesellschaft). Andrew Lang included it in The Yellow Fairy Book (1894) and Ruth Manning-Sanders included it in A Book of Dwarfs (1964).

"The Hazel Branch" from Grimms' Fairy Tales claims that hazel branches offer the greatest protection from snakes and other things that creep on the earth.

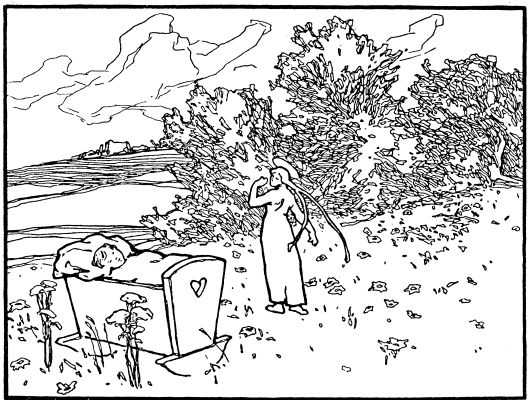

In the Grimm tale "Cinderella", a hazel branch is planted by the protagonist at her mother's grave and grows into a tree that is the site where the girl's wishes are granted by birds. “Shake your branches, little tree, Toss gold and silver down on me.” In this version of Cinderella, the hazel tree and the birds take on the role of fairy godmother.

ROMEO & JULIET

Mercutio is a fictional character in William Shakespeare's 1597 tragedy, Romeo and Juliet. Some of his lines include:

"Thou, why, thou wilt quarrel with a man that hath a hair more or a hair less in his beard than thou hast. Thou wilt quarrel with a man for cracking nuts, having no other reason but because thou hast hazel eyes. What eye but such an eye would spy out such a quarrel?"

"O, then, I see Queen Mab hath been with you. She is the fairies' midwife, and she comes In shape no bigger than an agate-stone On the fore-finger of an alderman, Drawn with a team of little atomies Athwart men's noses as they lie asleep; Her wagon-spokes made of long spiders' legs, The cover of the wings of grasshoppers, The traces of the smallest spider's web, The collars of the moonshine's watery beams, Her whip of cricket's bone, the lash of film, Her wagoner a small grey-coated gnat, Not so big as a round little worm Prick'd from the lazy finger of a maid; Her chariot is an empty hazel-nut Made by the joiner squirrel or old grub, Time out o' mind the fairies' coachmakers. And in this state she gallops night by night Through lovers' brains, and then they dream of love; O'er courtiers' knees, that dream on court'sies straight, O'er lawyers' fingers, who straight dream on fees, O'er ladies ' lips, who straight on kisses dream, Which oft the angry Mab with blisters plagues, Because their breaths with sweetmeats tainted are: Sometime she gallops o'er a courtier's nose, And then dreams he of smelling out a suit; And sometime comes she with a tithe-pig's tail Tickling a parson's nose as a' lies asleep, Then dreams, he of another benefice: Sometime she driveth o'er a soldier's neck, And then dreams he of cutting foreign throats, Of breaches, ambuscadoes, Spanish blades, Of healths five-fathom deep; and then anon Drums in his ear, at which he starts and wakes, And being thus frighted swears a prayer or two And sleeps again. This is that very Mab That plats the manes of horses in the night, And bakes the elflocks in foul sluttish hairs, Which once untangled, much misfortune bodes: This is the hag, when maids lie on their backs, That presses them and learns them first to bear, Making them women of good carriage: This is she—"

THE TAMING OF THE SHREW

Petruchio is the male protagonist in Shakespeare's The Taming of the Shrew (c. 1590–1594). Some of his lines include:

O sland'rous world! Kate like the hazel-twig Is straight and slender, and as brown in hue As hazel-nuts, and sweeter than the kernels. O, let me see thee walk. Thou dost not halt.

w.b. yeats

THE SONG OF WANDERING AENGUS

by William Butler Yeats

I went out to the hazel wood,

Because a fire was in my head,

And cut and peeled a hazel wand,

And hooked a berry to a thread;

And when white moths were on the wing,

And moth-like stars were flickering out,

I dropped the berry in a stream

And caught a little silver trout.

When I had laid it on the floor

I went to blow the fire a-flame,

But something rustled on the floor,

And someone called me by my name:

It had become a glimmering girl

With apple blossom in her hair

Who called me by my name and ran

And faded through the brightening air.

Though I am old with wandering

Through hollow lands and hilly lands,

I will find out where she has gone,

And kiss her lips and take her hands;

And walk among long dappled grass,

And pluck till time and times are done,

The silver apples of the moon,

The golden apples of the sun.

Source: The Wind Among the Reeds (1899)

At least 21 species of fungus have a mutualistic relationship with hazel. Lactarius pyrogalus grows almost exclusively on hazel, and hazel is one of two kinds of host for the rare Hypocreopsis rhododendri. In the UK, five species of moth are specialised to feed on hazel including Parornix devoniella. Animals which eat hazelnuts include red deer, dormouse and red squirrel.

hazel gloves

Hypocreopsis rhododendri is an ascomycete fungus. It is commonly known as hazel gloves due to the resemblance of its orange-brown, radiating lobes to rubber gloves, and because it is found on hazel (Corylus avellana) stems. Hypocreopsis rhododendri is found on the hyperoceanic west coasts of Britain and Ireland, in the Atlantic Pyrenees in south western France, and in the Appalachian mountains in the eastern United States. In the Appalachian mountains, H. rhododendri was originally found growing on Rhododendron maximum, and was subsequently found on Kalmia latifolia and Quercus sp. In Europe, H. rhododendri is found in Atlantic hazel woodland, mainly on hazel stems. It has never been found on Rhododendron species. Although H. rhododendri is found on woody stems, it has been suggested that it is not a wood-decay fungus, but is instead a parasite of the wood-decay fungus Hymenochaete corrugata.

Script Lichen

A script lichen, or graphid lichen, is a member of a group of lichens which have spore producing structures that look like writing on the lichen body. The structures are elongated and narrow apothecia called lirellae, which look like short scribbles on the thallus. "Graphid" is derived from Greek for "writing". Several rare species of Graphidion lichen depend on hazel trees.

Lactarius pyrogalus, commonly known as the fire-milk lactarius, is a species of inedible mushroom in genus Lactarius. The generic name Lactarius means producing milk (lactating) - a reference to the milky latex that is exuded from the gills of milkcap fungi when they are cut or torn. The specific epithet pyrogalus is a Latin adjective meaning fire milk - a reference to the extremely acrid latex within the flesh of this innocuous-looking milkcap. It is greyish and differentiated from other grey Lactarius by its widely spaced, yellow gills. It is found on the forest floor in mixed woodland, especially at the base of hazel trees. It is particularly common in hazel woodland managed for coppice. It can also be found elsewhere on the ground in mixed woodland. It is found in the autumn months of August, September and October. The well-spaced, yellow gills differentiate it from other greyish Lactarius species. The spores are amyloid, meaning they stain dark blue in Melzer's reagent, and feature an incomplete net. Lactarius pyrogalus has a very hot, acrid taste and is acidic. It is due to this taste that it received both its English name, fire-milk lactarius, and its scientific name, with "pyrogalus" translating as "fire milk". Despite not being poisonous, it is not regarded as edible and should be avoided. This is unlike its relative, the saffron milk-cap (L. deliciosus), which is regarded as a choice mushroom.

RED SQUIRREL

The red squirrel or Eurasian red squirrel (Sciurus vulgaris) is a species of tree squirrel in the genus Sciurus common throughout Europe and Asia. The red squirrel is an arboreal, primarily herbivorous rodent. In Great Britain, Ireland, and in Italy numbers have decreased drastically in recent years. This decline is associated with the introduction by humans of the eastern grey squirrel (Sciurus carolinensis) from North America. However, the population in Scotland is stabilising due to conservation efforts, awareness and the increasing population of the pine marten, a European predator that selectively controls grey squirrels.

The red squirrel eats mostly the seeds of trees, neatly stripping conifer cones to get at the seeds within, fungi, nuts (especially hazelnuts but also beech, chestnuts and acorns), berries, vegetables, garden flowers, tree sap and young shoots. More rarely, red squirrels may also eat bird eggs or nestlings. A Swedish study shows that out of 600 stomach contents of red squirrels examined, only 4 contained remnants of birds or eggs. A red squirrel burying hazelnuts Squirrel on a tree Excess food is put into caches called "middens", either buried or in nooks or holes in trees, and eaten when food is scarce. Although the red squirrel remembers where it created caches at a better-than-chance level, its spatial memory is substantially less accurate and durable than that of grey squirrels. Between 60% and 80% of its active period may be spent foraging and feeding. The active period for the red squirrel is in the morning and in the late afternoon and evening. It often rests in its nest in the middle of the day, avoiding the heat and the high visibility to birds of prey that are dangers during these hours. During the winter, this mid-day rest is often much briefer, or absent entirely, although harsh weather may cause the animal to stay in its nest for days at a time.

In Norse mythology, Ratatoskr is a red squirrel who runs up and down with messages in the world tree, Yggdrasil, and spreads gossip. In particular, he carried messages between the unnamed eagle at the top of Yggdrasill and the wyrm Níðhöggr beneath its roots. The red squirrel used to be widely hunted for its pelt. In Finland, squirrel pelts were used as currency in ancient times, before the introduction of coinage. The expression "squirrel pelt" is still widely understood there to be a reference to money. It has been suggested that the trade in red squirrel fur, highly prized in the medieval period and intensively traded, may have been responsible for the leprosy epidemic in medieval Europe. Within Great Britain, widespread leprosy is found early in East Anglia, to which many of the squirrel furs were traded, and the strain is the same as that found in modern red squirrels on Brownsea Island. The red squirrel is the national mammal of Denmark. Red squirrels are a common feature in English heraldry, where they are always depicted sitting up and often in the act of cracking a nut.

The American red squirrel (Tamiasciurus hudsonicus) is one of three species of tree squirrels currently classified in the genus Tamiasciurus, known as the pine squirrels (the others are the Douglas squirrel, T. douglasii, and the southwestern red squirrel, T. fremonti). The American red squirrel is variously known as the pine squirrel or piney squirrel, North American red squirrel, chickaree, or simply red squirrel.

It feeds primarily on the seeds of conifer cones, and is widely distributed across much of the United States and Canada wherever conifers are common, except in the southwestern United States, where it is replaced by the formerly conspecific southwestern red squirrel, and along the Pacific coast of the United States, where its cousin the Douglas squirrel is found instead. The squirrel has been expanding its range into hardwood forests. An isolated population of red squirrels in Arizona has experienced considerable declines in population size. In 1987, this portion of the population was listed as an endangered species.

American red squirrels are primarily granivores, but incorporate other food items into their diets opportunistically. In The Yukon, extensive behavioral observations suggest white spruce seeds (Picea glauca) comprise more than 50% of a red squirrel's diet, but squirrels have also been observed eating spruce buds and needles, mushrooms, willow (Salix sp.) leaves, poplar (Populus sp.) buds and catkins, bearberry (Arctostaphylos sp.) flowers and berries, and animal material such as bird eggs or even snowshoe hare leverets (young). White spruce cones mature in late July and are harvested by red squirrels in August and September. These harvested cones are stored in a central cache and provide energy and nutrients for survival over the winter and reproduction the following spring. The fallen scales from consumed seed cones can collect in piles, called middens, up to twelve meters across. White spruce exhibits two- to six-year masting cycles, where a year of superabundant cone production (mast year) is followed by several years in which few cones are produced. American red squirrel territories may contain one or several middens. American red squirrels eat a variety of mushroom species, including some that are deadly to humans.

RED DEER

The red deer (Cervus elaphus) is one of the largest deer species. A male red deer is called a stag or hart, and a female is called a hind. The red deer inhabits most of Europe, the Caucasus Mountains region, Anatolia, Iran, and parts of western Asia. It also inhabits the Atlas Mountains of Northern Africa; being the only living species of deer to inhabit Africa. Red deer have been introduced to other areas, including Australia, New Zealand, the United States, Canada, Peru, Uruguay, Chile and Argentina. In many parts of the world, the meat (venison) from red deer is used as a food source.

Red deer are widely depicted in cave art found throughout European caves, with some of the artwork dating from as early as 40,000 years ago, during the Upper Paleolithic. Siberian cave art from the Neolithic of 7,000 years ago has abundant depictions of red deer, including what can be described as spiritual artwork, indicating the importance of this mammal to the peoples of that region (Note: these animals were most likely wapiti (C. canadensis) in Siberia, not red deer). Red deer are also often depicted on Pictish stones (circa 550–850 AD), from the early medieval period in Scotland, usually as prey animals for human or animal predators. In medieval hunting, the red deer was the most prestigious quarry, especially the mature stag, which in England was called a hart.

The red deer can produce 10 to 15 kg (20 to 35 lb) of antler velvet annually.[citation needed] On ranches in New Zealand, China, Siberia, and elsewhere, this velvet is collected and sold to markets in East Asia, where it is used for holistic medicines, with South Korea being the primary consumer. In Russia, a medication produced from antler velvet is sold under the brand name Pantokrin (Russian: Пантокри́н; Latin: Pantocrinum).[citation needed] The antlers themselves are also believed by East Asians to have medicinal purposes and are often ground up and used in small quantities.

Deer hair products are also used in the fly fishing industry, being used to tie flies.[citation needed] Deer antlers are also used for decorative purposes and have been used for artwork, furniture and other novelty items. Deer antlers were and still are the source material for horn furniture. Already in the 15th century trophies of case were used for clothes hook, storage racks and chandeliers, the so-called Lusterweibchen. In the 19th century the European nobility discovered red deer antlers as perfect decorations for their manors and hunting castles.

HAZEL DORMOUSE

The hazel dormouse or common dormouse (Muscardinus avellanarius) is a small dormouse species native to Europe and the only living species in the genus Muscardinus. The hazel dormouse is native to northern Europe and Asia Minor. It is the only dormouse native to the British Isles, and is therefore often referred to simply as the "dormouse" in British sources, although the edible dormouse, Glis glis, has been accidentally introduced and now has an established population in South East England. Though Ireland has no native dormouse, the hazel dormouse was discovered in County Kildare in 2010, and appears to be spreading rapidly, helped by the prevalence of hedgerows in the Irish countryside.

This small mammal has reddish brown fur that can vary up to golden-brown or yellow-orange-brown becoming lighter in the lower part. Eyes are large and black. Ears are small and not very developed, while the tail is long and completely covered with hair. It is a nocturnal creature and spends most of its waking hours among the branches of trees looking for food. It will make long detours rather than come down to the ground and expose itself to danger. The hazel dormouse hibernates from October to April–May. The hazel dormouse spends a large proportion of its life sleeping − either hibernating in winter or in torpor in summer.

Examination of hazelnuts may show a neat, round hole in the shell. This indicates it has been opened by a small rodent, e.g., the dormouse, wood mouse, or bank vole. Other animals, such as squirrels or jays, will either split the shell completely in half or make a jagged hole in it.

Further examination reveals the cut surface of the hole has toothmarks which follow the direction of the shell. In addition, there will be toothmarks on the outer surface of the nut, at an angle of about 45 degrees to the cut surface.

The hazel dormouse requires a variety of arboreal foods to survive. It eats berries and nuts and other fruit with hazelnuts being the main food for fattening up before hibernation. The dormouse also eats hornbeam and blackthorn fruit where hazel is scarce. Other food sources are the buds of young leaves, and flowers which provide nectar and pollen. The dormouse also eats insects found on food-source trees, particularly aphids and caterpillars.

The oldest fossils of the genus Muscardinus date to the Serravallian stage of the Middle Miocene approximately 13.8 to 11.6 million years ago in what is now Spain. The oldest fossils of the modern species date to the Early Pleistocene.

The hazel dormouse is protected by and in UK under the Wildlife and Countryside Act.

misc

Nutella is a brand of sweetened hazelnut cocoa spread. Nutella is manufactured by the Italian company Ferrero and was first introduced in 1964.

Ferrero was using 25 percent of the global supply of hazelnuts at the time the source article was compiled, though not all of this was used exclusively in Nutella.

Gianduia or gianduja is a homogeneous blend of chocolate with 30% hazelnut paste, invented in Turin during Napoleon's regency (1796–1814). It can be consumed in the form of bars or as a filling for chocolates.

The Continental System, imposed by Napoleon in 1806, prevented British goods from entering European ports under French control, putting a strain on cocoa supplies. A chocolatier in Turin named Michele Prochet extended the little chocolate he had by mixing it with hazelnuts from the Langhe hills south of Turin. It is unclear when gianduja bars were made for the first time. However, Kohler is generally credited for the addition of (whole) hazelnuts to chocolate bars in 1830. And it is also known that, in 1852, Turin-based chocolate manufacturer Caffarel invented gianduiotto, which is a small ingot-shaped gianduja. In 1951, Pietro Ferrero invented a creamy spread based on Gianduja, which became the precursor of Nutella.

It takes its name from Gianduja, a Carnival and marionette character who represents the archetypal Piedmontese, natives of the Italian region where hazelnut confectionery is common.

The gianduiotto is chocolate originally from Piedmont, in northern Italy. Gianduiotti are shaped like ingots and individually wrapped in a (usually) gold- or silver-colored foil cover. It is a specialty of Turin, and takes its name from gianduja, the preparation of chocolate and hazelnut used for gianduiotti and other sweets (including Nutella and bicerin di Gianduiotto).

This preparation itself is named after Gianduja, a mask in commedia dell'arte, a type of Italian theater, that represents the archetypal Piedmontese. Indeed, Gianduja's hat inspired the shape of the gianduiotto.

Wikipedia suggests the hat is the tricorn hat aka the cocked hat (He is dressed, in the usual version with a tricorn hat and a brown jacket with red borders.) Maybe they meant the bicorn? Some interesting history with both so...

the

hazel

in the

unicorn tapestries

Hazel appears in four of the unicorn tapestries

"In The Unicorn is Killed and Brought Back to the Castle, a hazel in both fruit and flower is prominently depicted in the lower left corner. Perched on a branch, a red squirrel clutches a nut in his paw. He or she may not be quite as bad as an elf, but Norse and Germanic myth claims that squirrels were messengers between spirits of the underworld who lived at the base of trees and the gods above." — Christina Alphonso

REFERENCES

GENERAL

gianduja resembles a bar of chocolate. It is softer on the tooth than a plain chocolate bar (because of the oil from the hazelnuts)

FUNGUS

- Coppins A.M. & Coppins, B.J. (2010). Atlantic hazel. Scottish Natural Heritage.

- Thaxter R. (1922) Note on Two Remarkable Ascomycetes. Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 57, 425-434.

- Ainsworth A.M. (2003) Report on hazel gloves Hypocreopsis rhododendri, a UK BAP ascomycete fungus. English Nature Research Report No. 541. English Nature, Peterborough.

- Buchanan P.K. & May T.W. (2003). Conservation of New Zealand and Australian fungi. New Zealand Journal of Botany, 41, 407-421.

- Hansen L. & Knudsen H. (2000). Nordic Macromycetes Vol. 1. Ascomycetes. Nordsvam, Copenhagen.

- Hypocreopsis rhododendri in Index Fungorum

- Report on hazel gloves Hypocreopsis rhododendri, a UK BAP ascomycete fungus. English Nature Research Report.

- Hazel gloves. Scottish Natural Heritage.

- Scottish Fungi: Hazel gloves research news.

- “Lactarius pyrogalus (Bull.) Fr. 1838″. MycoBank. International Mycological Association. Retrieved 2011-06-06.

- Phillips, Roger (1981). Mushrooms and Other Fungi of Great Britain and Europe. London: Pan Books. p. 85. ISBN 0-330-26441-9.

- Roody, William C. (2003). Mushrooms of West Virginia and the Central Appalachians. Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky. p. 100. ISBN 978-0-8131-9039-6. Retrieved 2008-07-31.

- Pegler, David N. (1983). Mushrooms and Toadstools. London: Mitchell Beazley Publishing. p. 78. ISBN 0-85533-500-9.

- Jordan, Michael (2004). The Encyclopedia of Fungi of Britain and Europe. London: Frances Lincoln. p. 306. ISBN 978-0-7112-2378-3. Retrieved 2008-07-31.[permanent dead link]

- Sterry, Paul (1997). Complete British Wildlife. HarperCollins. p. 352. ISBN 978-0-583-33638-3.

- Phillips, 80.

- First Nature website

- What is a lichen?, Australian National Botanical Garden

- Jungle Dragon website

MESOLITHIC AND NEOLITHIC HAZELNUTS

- “Mesolithic food industry on Colonsay” Dec 1995) British Archaeology. No. 5. Retrieved 25 May 2008.

- Facts and Details website

- Gershon, Livia, Hazelnut Shell Sheds Light on Life in Scotland More Than 10,000 Years Ago, Smithsonian Magazine website March 10, 2021

- Moffat, Alistair (2005) Before Scotland: The Story of Scotland Before History. London. Thames & Hudson. p. 91–2.

WANDS

- Tribe, Shawn, Lost Romanitas: The Virgula Poenitentiaria — Or Penitential Wand / Rod, The Litigurical Arts Journal, February 18, 2022

- Zuhlsdorf, Fr John, Ask Father:What’s up with the ‘penitential wand’ and indulgences? Fr Z’s Blog 27 December 2016

- Ibrey, The Custom of the Penitential Rod, Reddit.com 2019

ogham

- McManus, Damian (1991). A Guide to Ogam. Maynooth Monographs. Vol. 4. Co. Kildare, Ireland: An Sagart. p. 37. ISBN 1-870684-75-3. ISSN 0790-8806.

The name of the ninth letter of the alphabet is the word for ‘hazel-tree’, Old Irish coll, cognate with Welsh collen pl. cyll hazel-tree(s), Latin corulus from the root *kos(e)lo-. The etymology confirms /k/ (as opposed to /kʶ/, see the next letter) as the value of this letter in Primitive Irish.

- McManus, Damian (1988). “Irish Letter-Names and Their Kennings”. Ériu. 39: 127–168. JSTOR 30024135.

- Wikipedia Forfeda page https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Forfeda

DIVINATION BY NUTS

- Williams, Caitlin, Fantastical Austen – Happy Nutcrack Day, Jane Austen Variations website, October 27, 2016

- The Hazel Tree, Scottish Country Dance of the Day website (this page also features a dance called Hazel Tree and links to a recipe for some kind of hazelnut cake)

TWO SHAKES OF A LAMB'S TAIL, CATKINS AND MORE

- ORDER OF BARDS, OVATES AND DRUIDS , “Hazel” Druidry website

FILBERTS, PHILBERTS AND FEAST DAYS

- Woolf, Jo, A Wand of Hazel, The Hazel Tree website

Well of Wisdom

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wells_in_the_Irish_Dindsenchas

- Monaghan, Patricia (2004), The Encyclopedia of Celtic Mythology and Folklore, “Bóand”, p.50

- Ford, Patrick K. (1974), “The Well of Nechtan and “La Gloire Lumineuse””, in Larson, Gerald J.; Littleton, C. Scott; Puhvel, Jaan (eds.), Myth in Indo-European Antiquity, pp. 67–74

- Dumézil, Georges (1963), “Le puits de Nechtan”, Celtica: Journal of the School of Celtic Studies (in French), 6

- Scottish Studies, 1962, p. 62

- O’Beirne Crowe, J. (1872), “Ancient Lake Legends of Ireland. No. II. The Vision of Cathair Mor, King of Leinster, and Afterwards Monarch of Ireland, Foreboding the Origin of Loch Garman (Wexford Haven)”, The Journal of the Royal Historical and Archaeological Association of Ireland, 4th series, 2 (1): 26–49, JSTOR 25506605

- Greer, Mary K. (1996). Women of the Golden Dawn. Park Street Press. p. 197. ISBN 978-0-89281-607-1.

- O’Curry, Eugene (1883), On the Manners and Customs of the Ancient Irish, vol. 2, ISBN 9780876960103

- Stokes, Whitley, ed. (1894), “The Prose Tales from the Rennes Dindshenchas”, Revue Celtique (in Ga and English), 15, [Tales 33-80], pp.418–484 , e-text via CELT : text and translation

- Meyer, Kuno; Nutt, Alfred (1895), “The Voyage of Bran Son of Febal (Part 1)”, Grimm Library, London: David Nut, no. 4

- Meyer, Kuno; Nutt, Alfred (1897), “The Voyage of Bran Son of Febal (Part 2)”, Grimm Library, London: David Nut, no. 6

- Gwynn, Edward, ed. (1913), “The Metrical Dindshenchas Part 3”, Royal Irish Academy Todd Lecture Series, Hodges, Figgis, & Co., Dublin ; Williams and Norgate, London, vol. X , e-text at CELT : text and translation

- MacKillop, James (2004), A Dictionary of Celtic Mythology, Oxford University Press

Divination by nuts

Divination by nuts