The enzyme juvenile hormone esterase (EC 3.1.1.59, systematic name methyl-(2E,6E,10R)-10,11-epoxy-3,7,11-trimethyltrideca-2,6-dienoate acylhydrolase, JH esterase) catalyzes the hydrolysis of juvenile hormone:

- (1) juvenile hormone I + H2O = juvenile hormone I acid + methanol

- (2) juvenile hormone III + H2O = juvenile hormone III acid + methanol

Nomenclature and function

This enzyme belongs to the family of hydrolases, specifically those acting on carboxylic ester bonds. The systematic name of this enzyme class is methyl-(2E,6E)-(10R,11S)-10,11-epoxy-3,7,11-trimethyltrideca-2,6-dienoate acylhydrolase. Other names in common use include JH esterase, juvenile hormone esterase, and juvenile hormone carboxyesterase.

Juvenile hormone (JH) controls insect metamorphosis.

- Gilbert et al., 1977

High JH titers maintain the larval state while a decrease in the JH titer initiates the pupation sequence as well as a change in tissue commitment away from synthesis of larval tissues to pupal tissues at the pupal stage.The drop in JH titer at the beginning of the last larval instar in the Lepidoptera appears to be due to a combination of increased metabolism and decreased synthesis. In the Lepidoptera, JH is initially metabolized by ester hydrolysis; esterases capable of hydrolyzing JH are detectable in the hemolymph at times during the last larval instar that appear to coincide with reported drops in the JH titre. The JHE’s are also selective for the 2E methyl ester of the naturally occurring JH’s. These studies suggest that the JHE’s may be important in the regulation of the JH titre and therefore involved in the initiation of and the commitment to the pupal stage. JHE’s appear to be produced by the fat body and this production can be stimulated by exogenous JH in Hyalophora pupae, a stage devoid of JHE activity. Stimulation of JHE activity by JH has also been noted recently in adults of Leptinotarsa decemlineata and pupae of Galleria mellonella. However, to date, no reported studies have examined this phenomenon during the last larval instar when these enzymes are thought to be of primary importance. Thus this laboratory undertook an investigation of the hemolymph JHE regulation during the last larval instar of the cabbage looper, Trichoplusia ni.

- Nijhout and Williams, 1974

- Riddiford, 1976

- Nowock and GILBERT, 1976a; Sanburg et al., 1975a; Sanburg et al., 1975b

- Nijhout, 1975

- Hammock and Quistad, 1976; Slade and Zibitt, 1972

- Vince and Gilbert, 1977:Sparks, 1979 #1170; Weirich and Wren, 1973

- Hammock et al., 1977; Weirich and Wren, 1973; Weirich and Wren, 1976

- Hammock et al., 1975; Nowock and Gilbert, 1976b; Whitmore et al., 1974

- Whitmore, 1972 #1160;Whitmore et al., 1974

- Kramer, 1978

- Reddy et al., 1979

Hemolymph, or haemolymph, is a fluid, analogous to the blood in vertebrates, that circulates in the interior of the arthropod (invertebrate) body, remaining in direct contact with the animal’s tissues. It is composed of a fluid plasma in which hemolymph cells called hemocytes are suspended. In addition to hemocytes, the plasma also contains many chemicals. It is the major tissue type of the open circulatory system characteristic of arthropods (for example, arachnids, crustaceans and insects). In addition, some non-arthropods such as mollusks possess a hemolymphatic circulatory system. Oxygen-transport systems were long thought unnecessary in insects, but ancestral and functional hemocyanin has been found in the hemolymph. Insect “blood” generally does not carry hemoglobin, although hemoglobin may be present in the tracheal system instead and play some role in respiration. In the grasshopper, the closed portion of the system consists of tubular hearts and an aorta running along the dorsal side of the insect. The hearts pump hemolymph into the sinuses of the hemocoel where exchanges of materials take place. The volume of hemolymph needed for such a system is kept to a minimum by a reduction in the size of the body cavity. The hemocoel is divided into chambers called sinuses. Coordinated movements of the body muscles gradually bring the hemolymph back to the dorsal sinus surrounding the hearts. Between contractions, tiny valves in the wall of the hearts open and allow hemolymph to enter. Hemolymph fills all of the interior (the hemocoel) of the animal’s body and surrounds all cells. It contains hemocyanin, a copper-based protein that turns blue when oxygenated, instead of the iron-based hemoglobin in red blood cells found in vertebrates, giving hemolymph a blue-green color rather than the red color of vertebrate blood. When not oxygenated, hemolymph quickly loses its color and appears grey. The hemolymph of lower arthropods, including most insects, is not used for oxygen transport because these animals respirate through other means, such as tracheas, but it does contain nutrients such as proteins and sugars. Muscular movements by the animal during locomotion can facilitate hemolymph movement, but diverting flow from one area to another is limited. When the heart relaxes, hemolymph is drawn back toward the heart through open-ended pores called ostia. Note that the term “ostia” is not specific to insect circulation; it literally means “doors” or “openings”, and must be understood in context. Hemolymph can contain nucleating agents that confer extra cellular freezing protection. Such nucleating agents have been found in the hemolymph of insects of several orders, i.e., Coleoptera (beetles), Diptera (flies), and Hymenoptera.

- Inorganic

- Hemolymph is composed of water, inorganic salts (mostly sodium, chlorine, potassium, magnesium, and calcium), and organic compounds (mostly carbohydrates, proteins, and lipids). The primary oxygen transporter molecule is hemocyanin.

- Amino acids

- Arthropod hemolymph contains high levels of free amino acids. Most amino acids are present but their relative concentrations vary from species to species. Concentrations of amino acids also vary according to the arthropod stage of development. An example of this is the silkworm and its need for glycine in the production of silk.

- Proteins

- Proteins present in the hemolymph vary in quantity during the course of development. These proteins are classified by their functions: chroma proteins, protease inhibitors, storage, lipid transport, enzymes, the vitellogenins, and those involved in the immune responses of arthropods. Some hemolymphic proteins incorporate carbohydrates and lipids into the structure.

- Other organic constituents

- Nitrogen metabolism end products are present in the hemolymph in low concentrations. These include ammonia, allantoin, uric acid, and urea. Arthropod hormones are present, most notably the juvenile hormone. Trehalose can be present and sometimes in great amounts along with glucose. These sugar levels are maintained by the control of hormones. Other carbohydrates can be present. These include inositol, sugar alcohol, hexosamines, mannitol, glycerol and those components that are precursors to chitin. Free lipids are present and are used as fuel for flight. Hemocytes Main article: Hemocyte (invertebrate immune system cell) There are free-floating cells, the hemocytes, within the hemolymph. They play a role in the arthropod immune system. The immune system resides in the hemolymph. This open system might appear to be inefficient compared to the closed circulatory systems of the vertebrates, but the two systems have very different demands placed on them. In vertebrates, the circulatory system is responsible for transporting oxygen to all the tissues and removing carbon dioxide from them. It is this requirement that establishes the level of performance demanded of the system. The efficiency of the vertebrate system is far greater than is needed for transporting nutrients, hormones, and so on, whereas in insects, exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide occurs in the tracheal system. Hemolymph plays no part in the process in most insects. Only in a few insects living in low-oxygen environments are there hemoglobin-like molecules that bind oxygen and transport it to the tissues. Therefore, the demands placed upon the system are much lower. Some arthropods and most molluscs possess the copper-containing hemocyanin, however, for oxygen transport.[citation needed] In some species, hemolymph has other uses than just being a blood analogue. As the insect or arachnid grows, the hemolymph works something like a hydraulic system, enabling the insect or arachnid to expand segments before they are sclerotized. It can also be used hydraulically as a means of assisting movement, such as in arachnid locomotion. Some species of insect or arachnid are able to autohaemorrhage when they are attacked by predators. Queens of the ant genus Leptanilla are fed with hemolymph produced by the larvae. On the other hand, Pemphigus spyrothecae utilize hemolymph as an adhesive, allowing the species to stick to predators and subsequently attack the predator; it was found that with larger predators, more aphids were stuck after the predator was defeated.

- Chapman, R.F. (1998). The Insects: Structure and Function (4th ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-57890-5.

- Wyatt, G. R. (1961). “The Biochemistry of Insect Hemolymph”. Annual Review of Entomology. 6: 75–102. doi:10.1146/annurev.en.06.010161.000451. S2CID 218693.

- Hagner-Holler, Silke; Schoen, Axel; Erker, Wolfgang; Marden, James H.; Rupprecht, Rainer; Decker, Heinz; Burmester, Thorsten (2004-01-20). “A respiratory hemocyanin from an insect”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 101 (3): 871–874. Bibcode:2004PNAS..101..871H. doi:10.1073/pnas.0305872101. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 321773. PMID 14715904.

- Hankeln, Thomas; Jaenicke, Viviane; Kiger, Laurent; Dewilde, Sylvia; Ungerechts, Guy; Schmidt, Marc; Urban, Joachim; Marden, Michael C.; Moens, Luc; Burmester, Thorsten (2002-06-04). “Characterization ofDrosophilaHemoglobin”. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (32): 29012–29017. doi:10.1074/jbc.m204009200. ISSN 0021-9258. PMID 12048208.

- Richards, O. W.; Davies, R.G. (1977). Imms’ General Textbook of Entomology: Volume 1: Structure, Physiology and Development Volume 2: Classification and Biology. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 0-412-61390-5.

- Zachariassen, Karl Erik; Baust, John G.; Lee, Richard E. (1982). “A method for quantitative determination of ice nucleating agents in insect hemolymph”. Cryobiology. 19 (2): 180–4. doi:10.1016/0011-2240(82)90139-0. PMID 7083885.

- Sowers, A.D; Young, S.P; Grosell, M.; Browdy, C.L.; Tomasso, J.R. (2006). “Hemolymph osmolality and cation concentrations in Litopenaeus vannamei during exposure to artificial sea salt or a mixed-ion solution: Relationship to potassium flux”. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology. 145 (2): 176–80. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.06.008. PMID 16861020.

- Chapman 1998, p. 108.

- Chapman 1998, p. 111.

- Chapman 1998, p. 114.

- Bateman, P. W.; Fleming, P. A. (2009). “There will be blood: Autohaemorrhage behaviour as part of the defence repertoire of an insect”. Journal of Zoology. 278 (4): 342–8. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2009.00582.x.

- Genus Leptanilla Australian Ants Online

- “Do insects have blood?”. Boston Globe. October 17, 2005. Archived from the original on October 2, 2022.

- Bolstad, Kat (May 2, 2008). “Blue Squid Blood – Murky Water”. Te Papa Tongarewa Museum of New Zealand. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015.

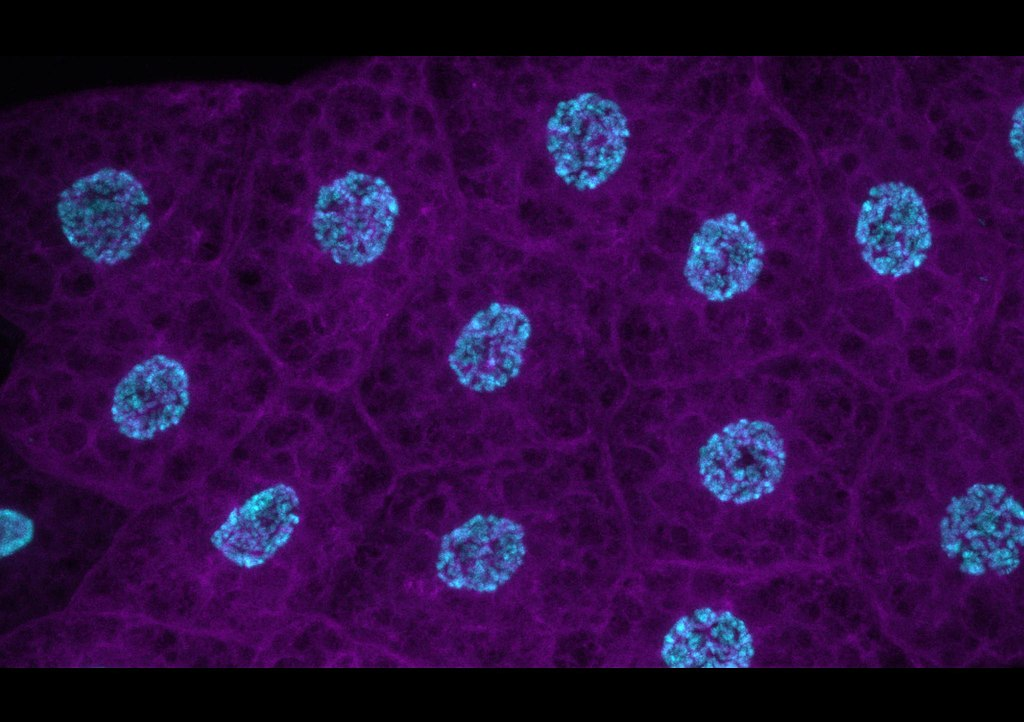

Fat body is a highly dynamic insect tissue composed primarily of storage cells. It is distributed throughout the insect’s internal body cavity (the haemocoel), in close proximity to the epidermis, digestive organs and ovaries. Its main functions are nutrient storage and metabolism, for which it is commonly compared to a combination of adipose tissue and liver in mammals. However, it may also serve a variety of other roles, such as: endocrine regulation, systemic immunity, vitellogenesis, and main site of production of antimicrobial molecules called antimicrobial peptides (or AMPs). Its presence, structure, cellular composition, location, and functions vary widely among insects, even between different species of the same genus or between developmental stages of the same individual, with other specialized organs taking over some or all of its functions. The fat body serves different roles including lipid storage and metabolism, endocrine regulation, and immunity. The fat body is of mesodermal origin and is normally composed of a network of thin sheets, ribbons or small nodules suspended in hemocoel by connective tissue and tracheae, so that most of its cells are in direct contact with hemolymph. The fat body has been best studied in insects. Nevertheless, it is present in other arthropod subphyla including Chelicerata, Crustacea, and all major classes of Myriapoda, although not all subtaxa.

- Arrese, Estela L.; Soulages, Jose L. (1 January 2010). “Insect Fat Body: Energy, Metabolism, and Regulation”. Annual Review of Entomology. 55 (1): 207–225. doi:10.1146/annurev-ento-112408-085356. PMC 3075550.

- Coons, Lewis B. (December 2013). “Fat body and nephrocytes”. In Sonenshine, Daniel E.; Roe, R. Michael (eds.). Biology of ticks. Oxford University Press. pp. 287–308. ISBN 978-0-19-974405-3.

- Chapman, R.F. (2013). Simpson, Stephen J.; Douglas, Angela E. (eds.). The Insects: Structure and Function. Cambridge University Press. pp. 132–145. ISBN 978-0-521-11389-2.

- Cohen, Ephraim (2009). “Fat Body”. In Resh, Vincent H.; Cardé, Ring T. (eds.). Encyclopedia of Insects. Academic Press. pp. 356–357. ISBN 978-0-08-092090-0.

JH esterase induction

Juvenile hormone esterase is induced by factors naturally occurring in the head of insects. In addition, it is induced by treatment of insects with either natural juvenile hormone, with JH I being the most potent inducer. Synthetic agonists of JH have been shown to possess this same activity, albeit at a lower potency than JH I. In another study, it has been shown that factors present in the head of the insect are potent inducers of JH activity. Starvation of lepidopteran larvae also induces appearance of JH esterase.

- Jones et al., 1980

- Sparks and Hammock, 1979

- Sparks et al., 1979

- Jones et al., 1980

- Sparks et al., 1983

JH esterase inhibitors

A number of compounds have been discovered which are potent inhibitors of JH esterase. Many of these are insecticides falling into two major structural groups, the phosphoamidothiolates and S-phenylphosphates; carbamate insecticides were also tested. By far the most potent inhibitor was an ethoxythiophenylphospamidothiolate, with IC50 < 1 nM. Of particular interest in this study is that ethyl and isopropyl analogs of natural JHs were NOT cleaved by the esterase, showing that it is methyl ester specific. JH I and JH III were tested at nominal concentrations of 5 μM. Later a trifluoromethyl ketone (3-octylthio-1,1,1-trifluoro-2-propanone) was shown to be a highly potent, high affinity slow, tight binding inhibitor of the JH esterase of Trichoplusia ni, the same Lepidopteran which was used in the other study in this section. This study reported very sophisticated kinetic analyses of the inhibition of this compound (acronym OTFP), JH I was shown to be degraded more readily by the enzyme than JH III, with a Km value about twice the value of JH III.

- Hammock et al., 1977

- Abdel-Aal et al., 1984

JH esterase fluctuations with time and relation to insect development

JH esterase and JH epoxide hydrolase are crucial in terminating the action of JH. The role of juvenile hormone binding proteins are also important, as they afford juvenile hormone protection from hydrolytic enzymes. This makes for a very complicated scenario that is difficult to investigate, and also difficult to distinguish between different species. Very detailed studies have been done on JH, JH acid, ecdysone, and JH titers have been done in precisely timed larvae of Manduca sexta as a function of development during the fifth larval stadium. In these larvae the principle JH are JH I, and JH II, with low levels of JH 0 and JH III. There is a large peak of JH I and II at the end of the fourth stadium, accompanied by lower levels of their acid metabolites. Then a broad peak of JH esterase starts on day 1.5 to day 4. Subsequently, ecdysteroid titers rise slightly on day 3.5, then a massive peak of ecdysteroid starting on day 5 persisting at somewhat lower levels to day 5. This is accompanied by a sharp peak of JH I and JH II, beginning on day 4 and ending on day 6. JH I acid titers are almost the same as JH I titer, except on day 7 when is a sharp peak of only JH I acid. This is just as ecdysteroid titers are decreasing. A very similar timing of peaks of JH esterase and ecdysone has been observed in Galleria mellonella. These data are consistent with a classical model for lepidopterans where JH is high at each larval molt, but must rise together with ecdysone prior to pupation to initiate the pupal molt. They are also consistent with a model advanced by others that corpora allata maintained in vitro of day 0 M. sexta larva secrete high levels of JH, but that the shift to producing only JH acid at day 4, which is then methylated by imaginal discs to generate the JH peak. However, secretion of the relative amounts of JH produced by CA of Manduca sexta has been found to differ considerably from in vivo titers. Investigation of JH titers in Trichoplusia ni have led to very similar conclusions as regards the timing of pulses of JH temporally and with respect to edysone secretion. However, the principle JH in this species is JH II. Injection of an esterase inhibitor, EPPAT, was found to increase juvenile hormone titers, and starvation was found to increase juvenile hormone titers. In addition, parasitization of larvae with Chelonus sp. (Hymenoptera) was found to decrease JH II titers, but to cause an increase in JH III titers, apparently derived from the parasite.

- Braun and Wyatt, 1995; De Kort and Granger, 1996; Plapp et al., 1998; Prestwich et al., 1996

- Baker et al., 1987

- Hwanghsu et al., 1979

- Sparagana et al., 1985; Sparagana et al., 1984

- Baker et al., 1987

- Jones et al., 1990

JH esterase protein structure

The crystal structure of esterase from the tobacco hornworm Manduca sexta has been solved in complex with the transition state analogue inhibitor 3-octylthio-1,1,1-trifluoropropan-2-one (OTFP) covalently bound to the active site. This crystal structure contains a long, hydrophobic binding pocket with the solvent-inaccessible catalytic triad located at the end. The structure explains many of the interactions observed between JHE and its substrates and inhibitors, such as the preference for methyl esters vs. ethyl or isopropyl esters, and long hydrophobic backbones. The enzyme is extremely efficient, with a cat/Km of at least 3 x 107 M-1 s-1. The primary sequence is 583 amino acids long, with a 22 amino acid protein. The calculated Mr of the active form is 62.1 kDa.

- Wogulis et al., 2006

Written References

- Abdel-Aal, Y.A.I., Roe, R., Hammock, B.D., 1984. Kinetic properties of the inhibition juvenile hormone esterase by two trifluoromethylketones and O-ethyl, S-phenyl phosphoramidothioate. Pest. Biochem. Physiol. 21, 232-241.

- Baker, F.C., Tsai, L.W., Reuter, C.C., Schooley, D.A., 1987. In vivo fluctuation of JH, JH acid, and ecdysteroid titer, and JH esterase activity, during development of fifth stadium Manduca sexta. Insect Biochem. 17, 989-996.

- Braun, R.P., Wyatt, G.R., 1995. Growth of the male accessory gland in adult locusts: Roles of juvenile hormone, JH esterase, and JH binding proteins. Arch.Insect Biochem.Physiol. 30, 383-400.

- De Kort, C.A.D., Granger, N.A., 1996. Regulation of JH titers: The relevance of degradative enzymes and binding proteins. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 33, 1-26.

- Gilbert, L.I., Goodman, W., Bollenbacher, W.E., 1977. Biochemistry of regulatory lipids and sterols in insects., in: Goodwin, T.W. (Ed.), Biochemistry of Lipids II. International Review of Biochemistry. University Park Press, Baltimore, pp. I-50.

- Hammock, B., Nowock, J., Goodman, W., Stamoudis, V., Gilbert, L.I., 1975. Influence of Hemolymph-Binding Protein on Juvenile-Hormone Stability and Distribution in Manduca Sexta Fat-Body and Imaginal Disks In vitro. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology 3, 167-184.

- Hammock, B.D., Quistad, G.B., 1976. The degradative metabolism of juvenoids by insects, in: Gilbert, L.I. (Ed.), The Juvenile Hormones. Plenum Press, New York, pp. 374–393.

- Hammock, B.D., Sparks, T.C., Mumby, S.M., 1977. Selective inhibition of JH esterases from cockroach hemolymph. Pest. Biochem. Physiol. 7, 517-530.

- Hwanghsu, K., Reddy, G., Kumaran, A.K., Bollenbacher, W.E., Gilbert, L.I., 1979. Correlations between Juvenile Hormone Esterase-Activity, Ecdysone Titer and Cellular Reprogramming in Galleria Mellonella. J. Insect Physiol. 25, 105-111.

- Jones, G., Hanzlik, T., Hammock, B.D., Schooley, D.A., Miller, C.A., Tsai, L.W., Baker, F.C., 1990. The Juvenile Hormone Titre During the Penultimate and Ultimate Larval Stadia of Trichoplusia ni. J. Insect Physiol. 36, 77-83.

- Jones, G., Wing, K.D., Jones, D., Hammock, B.D., 1980. The source and action of head factors regulating juvenile hormone esterase in larvae of the cabbage looper, Trichoplusia ni. J. Insect Physiol. 27, 85-91.

- Kramer, S.J., 1978. Regulation of the activity of JH-specific esterases in the Colorado potato beetle, Leptinotarsa decemlineata. J. Insect Physiol. 24, 743-747.

- Nijhout, H., Williams, C., 1974. Control of Moulting and Metamorphosis in the Tobacco Hornworm, Manduca Sexta (L.): Cessation of Juvenile Hormone Secretion as a Trigger for Pupation J. Exp. Biol. 61, 493-450.

- Nijhout, H.F., 1975. Dynamics of juvenile hormone action in larvae of the tobacco horn worm. Biological Bulletin of the Marine Biological Laboratory, Woods Hole 149, 568-579.

- Nowock, J., GILBERT, L., 1976a. In vitro analysis of factors regulating the juvenile hormone titer of insects, in: Kurstack, E., Maramorosch, K. (Eds.), Invertebrate Tissue Culture. Academic Press, New York, pp. 203–212.

- Nowock, J., Gilbert, L.I., 1976b. In vitro analysis of factors regulating the juvenile hormone titer of insects, in: K., K.E.a.M. (Ed.), Invertebrate Tissue Culture. Academic Press, New York, pp. 203–212.

- Plapp, F.W., Jr., Cariño, F.A., Wei, V.K., 1998. A juvenile hormone binding protein from the house fly and its possible relationship to insecticide resistance. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 37, 64-72.

- Prestwich, G.D., Wojtasek, H., Lentz, A.J., Rabinovich, J.M., 1996. Biochemistry of proteins that bind and metabolize juvenile hormones. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 32, 407-419.

- Reddy, G., Hwanghsu, K., Kumaran, A.K., 1979. Factors Influencing Juvenile Hormone Esterase-Activity in the Wax Moth, Galleria-Mellonella. J. Insect Physiol. 25, 65-71.

- Riddiford, L.M., 1976. Hormonal control of insect epidermal cell commitment in vitro. Nature 259, 115-117.

- Sanburg, L.L., Kramer, K.J., Kezdy, F.J., Law, J.H., 1975a. Juvenile hormone-specific esterases in the haemolymph of the tobacco hornworm, Manduca sexta. J. Insect Physiol. 21, 873-887.

- Sanburg, L.L., Kramer, K.J., Kezdy, F.J., Law, J.H., Oberlander, H., 1975b. Role of juvenile hormone esterases and carrier proteins in insect development. Nature 253, 266-267.

- Slade, M., Zibitt, C.H., 1972. Metabolism of Cecropia Juvenile Hormone in Insects and in Mammals, in: Menn, J.J., Beroza, M. (Eds.), Insect Juvenile Hormones: Chemistry and Action. Academic Press, New York, pp. 155–176.

- Sparagana, S.P., Bhaskaran, G., Barrera, P., 1985. Juvenile hormone acid methyltransferase activity in imaginal discs of Manduca sexta prepupae. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 2, 191-202.

- Sparagana, S.P., Bhaskaran, G., Dahm, K.H., Riddle, V., 1984. Juvenile hormone production, juvenile hormone esterase, and juvenile hormone acid methyltransferase in corpora allata of Manduca sexta. J. Exp. Zool. 230, 309-313.

- Sparks, T.C., Hammock, B.D., 1979. Induction and regulation of juvenile hormone esterases during the last larval instar of the cabbage looper, Trichoplusia ni. J. Insect Physiol. 25, 551-560.

- Sparks, T.C., Hammock, B.D., Riddiford, L.M., 1983. The haemolyph juvenile hormone esterase of Manduca sexta (L.)-inhibition and regulation. Insect Biochem. 13, 529-541.

- Sparks, T.C., Wing, K.D., Hammock, B.D., 1979. Effects of the anti hormone-hormone mimic ETB on the induction of insect juvenile hormone esterase in Trichoplusia ni. Life Sci. 25, 445-450.

- Vince, R.K., Gilbert, L.I., 1977. Juvenile hormone esterase activity in precisely timed last instar larvae and pharate pupae of Manduca sexta. Insect Biochem. 7, 115-120.

- Weirich, G., Wren, J., 1973. The substrate specificity of juvenile hormone esterase from Manduca sexta haemolymph. Life Sci. 13, 213-226.

- Weirich, G.F., Wren, J., 1976. Juvenile-hormone esterase in insect development: a comparative study. Physiological Zoology 49, 341-350.

- Whitmore, D., Gilbert, L.I., Ittycher.Pi, 1974. Origin of Hemolymph Carboxylesterases Induced by Insect Juvenile-Hormone. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology 1, 37-54.

- Wogulis, M., Wheelock, C.E., Kamita, S.G., Hinton, A.C., Whetstone, P.A., Hammock, B.D., Wilson, D.K., 2006. Structural Studies of a Potent Insect Maturation Inhibitor Bound to the Juvenile Hormone Esterase of Manduca sexta. Biochemistry 45, 4045-4057.

Further reading

- Foucher AL, McIntosh A, Douce G, Wastling J, Tait A, Turner CM (2006). “A proteomic analysis of arsenical drug resistance in Trypanosoma brucei“. Proteomics. 6 (9): 2726–32. doi:10.1002/pmic.200500419. PMID 16526094.

- Mitsui T, Riddiford LM, Bellamy G (1979). “Metabolism of juvenile hormone by the epidermis of the tobacco hornworm (Manduca sexta)”. Insect Biochem. 9 (6): 637–643. doi:10.1016/0020-1790(79)90103-3.

References

- Gilbert et al., 1977

- Nijhout and Williams, 1974

- Riddiford, 1976

- Nowock and GILBERT, 1976a; Sanburg et al., 1975a; Sanburg et al., 1975b

- Nijhout, 1975

- Hammock and Quistad, 1976; Slade and Zibitt, 1972

- Vince and Gilbert, 1977:Sparks, 1979 #1170; Weirich and Wren, 1973

- Hammock et al., 1977; Weirich and Wren, 1973; Weirich and Wren, 1976

- Hammock et al., 1975; Nowock and Gilbert, 1976b; Whitmore et al., 1974

- Whitmore, 1972 #1160;Whitmore et al., 1974

- Kramer, 1978

- Reddy et al., 1979

- Jones et al., 1980

- Sparks and Hammock, 1979

- Sparks et al., 1979

- Jones et al., 1980

- Sparks et al., 1983

- Hammock et al., 1977

- Abdel-Aal et al., 1984

- Braun and Wyatt, 1995; De Kort and Granger, 1996; Plapp et al., 1998; Prestwich et al., 1996

- Baker et al., 1987

- Hwanghsu et al., 1979

- Sparagana et al., 1985; Sparagana et al., 1984

- Baker et al., 1987

- Jones et al., 1990

- Wogulis et al., 2006

Leave a Reply