Reactive arthritis, also known as Reiter’s syndrome, is a form of inflammatory arthritis that develops in response to an infection in another part of the body (cross-reactivity). Coming into contact with bacteria and developing an infection can trigger the disease. By the time the patient presents with symptoms, often the “trigger” infection has been cured or is in remission in chronic cases, thus making determination of the initial cause difficult.

- American College of Rheumatology. “Reactive Arthritis”. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- Mayo Staff (5 March 2011). “Reactive Arthritis (Reiter’s Syndrome)”. Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 16 May 2011.

The arthritis often is coupled with other characteristic symptoms; this has been called Reiter’s syndrome, Reiter’s disease or Reiter’s arthritis. The term “reactive arthritis” is increasingly used as a substitute for this designation because of Hans Reiter‘s war crimes with the Nazi Party.

The manifestations of reactive arthritis include the following triad of symptoms: an inflammatory arthritis of large joints, inflammation of the eyes in the form of conjunctivitis or uveitis, and urethritis in men or cervicitis in women. Arthritis occurring alone following sexual exposure or enteric infection is also known as reactive arthritis. Patients can also present with mucocutaneous lesions, as well as psoriasis-like skin lesions such as circinate balanitis, and keratoderma blennorrhagicum. Enthesitis can involve the Achilles tendon resulting in heel pain. Not all affected persons have all the manifestations.

- H. Hunter Handsfield (2001). Color atlas and synopsis of sexually transmitted diseases, Volume 236. McGraw-Hill Professional. p. 148. ISBN 978-0-07-026033-7.

The clinical pattern of reactive arthritis commonly consists of an inflammation of fewer than five joints which often includes the knee or sacroiliac joint. The arthritis may be “additive” (more joints become inflamed in addition to the primarily affected one) or “migratory” (new joints become inflamed after the initially inflamed site has already improved).

- Primer on the Rheumatic Diseases, By John H. Klippel, page 218

- Rheumatology in Practice, By J. A. Pereira da Silva, Anthony D. Woolf page 5.9

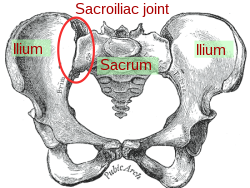

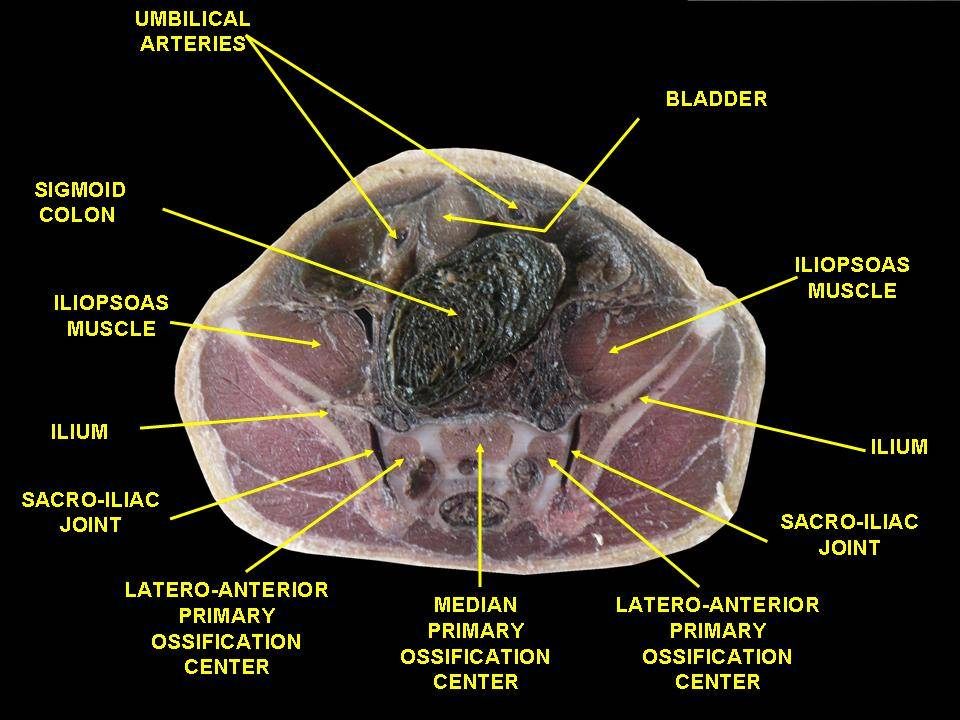

The sacroiliac joint or SI joint (SIJ) is the joint between the sacrum and the ilium bones of the pelvis, which are connected by strong ligaments. In humans, the sacrum supports the spine and is supported in turn by an ilium on each side. The joint is strong, supporting the entire weight of the upper body. It is a synovialplane joint with irregular elevations and depressions that produce interlocking of the two bones. The human body has two sacroiliac joints, one on the left and one on the right, that often match each other but are highly variable from person to person.

- Solonen, K. A. (1957). “The sacroiliac joint in the light of anatomical, roentgenological and clinical studies”. Acta Orthopaedica Scandinavica Supplementum. 27: 1–127. PMID 13478452.

Aging changes the characteristics of the sacroiliac joint. The joint’s surfaces are flat or planar in early life. Once walking ability is developed, the sacroiliac joint surfaces begin to develop distinct angular orientations and lose their planar or flat topography. They also develop an elevated ridge along the iliac surface and a depression along the sacral surface. The ridge and corresponding depression, along with the very strong ligaments, increase the sacroiliac joints’ stability and makes dislocations very rare. The fossae lumbales laterales (“dimples of Venus“) correspond to the superficial topography of the sacroiliac joints.

- Walker, Joan M. (1986). “Age-Related Differences in the Human Sacroiliac Joint: A Histological Study; Implications for Therapy”. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 7 (6): 325–34. doi:10.2519/jospt.1986.7.6.325. PMID 18802258.

- Alderink, Gordon J. (1991). “The Sacroiliac Joint: Review of Anatomy, Mechanics, and Function”. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 13 (2): 71–84. doi:10.2519/jospt.1991.13.2.71. PMID 18796854.

- Vleeming, A.; Schuenke, M. D.; Masi, A. T.; Carreiro, J. E.; Danneels, L.; Willard, F. H. (2012). “The sacroiliac joint: An overview of its anatomy, function and potential clinical implications”. Journal of Anatomy. 221 (6): 537–67. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2012.01564.x. PMC 3512279. PMID 22994881.

Ligaments

The ligaments of the sacroiliac joint include the following:

- Anterior sacroiliac ligament

- Interosseous sacroiliac ligament

- Posterior sacroiliac ligament

- Sacrotuberous ligament

- Sacrospinous ligament

- Vleeming, A.; Schuenke, M. D.; Masi, A. T.; Carreiro, J. E.; Danneels, L.; Willard, F. H. (2012). “The sacroiliac joint: An overview of its anatomy, function and potential clinical implications”. Journal of Anatomy. 221 (6): 537–67. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2012.01564.x. PMC 3512279. PMID 22994881.

The ligaments of the sacroiliac joint loosen during pregnancy due to the hormones estrogen and relaxin; this loosening, along with that of the related symphysis pubis, permits the pelvic joints to widen during the birthing process. The long SI ligaments may be palpated in thin persons for pain and compared from one side of the body to the other; however, the reliability and the validity of comparing ligaments for pain have currently not been shown. The interosseous ligaments are very short and run perpendicular from the iliac surface to the sacrum, they keep the auricular surfaces from abducting or opening/distracting.[citation needed]

- Fiani B, Sekhon M, Doan T, Bowers B, Covarrubias C, Barthelmass M, De Stefano F, Kondilis A. Sacroiliac Joint and Pelvic Dysfunction Due to Symphysiolysis in Postpartum Women. Cureus. 2021 Oct 9;13(10):e18619. doi: 10.7759/cureus.18619. PMID: 34786225; PMCID: PMC8580107.

- Aldabe D, Ribeiro DC, Milosavljevic S, Dawn Bussey M. Pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain and its relationship with relaxin levels during pregnancy: a systematic review. Eur Spine J. 2012 Sep;21(9):1769-76. doi: 10.1007/s00586-012-2162-x. Epub 2012 Feb 4. PMID: 22310881; PMCID: PMC3459115.

Inflammation and dysfunction

Main articles: Sacroiliitis and Sacroiliac joint dysfunction

Sacroiliitis refers to inflammation of one or both sacroiliac joints, and is one cause of low back pain. With sacroiliitis, the individual may experience pain in the low back, buttock or thigh, depending on the amount of inflammation.

Common mechanical problems of the sacroiliac joint are often called sacroiliac joint dysfunction (also termed SI joint dysfunction; SIJD). Sacroiliac joint dysfunction generally refers to pain in the sacroiliac joint region that is caused by abnormal motion in the sacroiliac joint—either too much or too little motion. It typically results in inflammation of the SI joint, or sacroiliitis.

Signs and symptoms

The following are signs and symptoms that may be associated with an SI joint (SIJ) problem:

- Mechanical SIJ dysfunction usually causes a dull unilateral low back pain.

- The pain is often a mild to moderate ache around the dimple or posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS) region.

- The pain may become worse and sharp while doing activities such as standing up from a seated position or lifting the knee towards the chest during stair climbing.

- Pain is typically on one side or the other (unilateral PSIS pain), but the pain can occasionally be bilateral.

- When the pain of SIJ dysfunction is severe (which is infrequent), there can be referred pain into the hip, groin, and occasionally down the leg, but rarely does the pain radiate below the knee.

- Pain can be referred from the SIJ down into the buttock or back of the thigh, and rarely to the foot.

- Low back pain and stiffness, often unilateral, that often increases with prolonged sitting or prolonged walking.

- Pain may occur during sexual intercourse; however, this is not specific to just sacroiliac joint problems.

The hormonal changes of menstruation, pregnancy, and lactation can affect the integrity of the ligament support around the SIJ, which is why women often find the days leading up to their period are when the pain is at its worst. During pregnancy, female hormones are released that allow the connective tissues in the body to relax. The relaxation is necessary so that during delivery, the female pelvis can stretch enough to allow birth. This stretching results in changes to the SIJs, making them overly mobile. Over a period of years, these changes can eventually lead to wear-and-tear arthritis. As would be expected, the more pregnancies a woman has, the higher her chances of SI joint problems. During the pregnancy, micro tears and small gas pockets can appear within the joint.[citation needed]

Muscle imbalance, trauma (e.g., falling on the buttock) and hormonal changes can all lead to SIJ dysfunction. Sacroiliac joint pain may be felt anteriorly; however, care must be taken to differentiate this from hip joint pain.

Women are considered more likely to suffer from sacroiliac pain than men, mostly because of structural and hormonal differences between the sexes, but so far no credible evidence exists that confirms this notion. Female anatomy often allows one fewer sacral segment to lock with the pelvis, and this may increase instability.

Reactive arthritis is an RF-seronegative, HLA-B27-linked arthritis often precipitated by genitourinary or gastrointestinal infections. The most common triggers are intestinal infections (with Salmonella, Shigella or Campylobacter) and sexually transmitted infections (with Chlamydia trachomatis); however, it also can happen after group A streptococcal infections.

- Ruddy, Shaun (2001). Kelley’s Textbook of Rheumatology, 6th Ed. W. B. Saunders. pp. 1055–1064. ISBN 978-0-7216-9033-9.

- Siala, Mariam; et al. (2008). “Analysis of bacterial DNA in synovial tissue of Tunisian patients with reactive and undifferentiated arthritis by broad-range PCR, cloning and sequencing”. Arthritis Research & Therapy. BioMed Central. 10 (2): R40. doi:10.1186/ar2398. PMC 2453759. PMID 18412942.

- Infectious Diseases Immunization Committee (1995). “Poststreptococcal arthritis”. The Canadian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 6 (3): 133–135. doi:10.1155/1995/470341. PMC 3327910. PMID 22514384.

- “Reactive Arthritis”. www.rheumatology.org. Retrieved 18 September 2019.

It most commonly strikes individuals aged 20–40 years of age, is more common in men than in women, and more common in white than in black people. This is owing to the high frequency of the HLA-B27 gene in the white population. It can occur in epidemic form. Patients with HIV have an increased risk of developing reactive arthritis as well.

- Sampaio-Barros PD, Bortoluzzo AB, Conde RA, Costallat LT, Samara AM, Bértolo MB (June 2010). “Undifferentiated spondyloarthritis: a longterm followup”. The Journal of Rheumatology. 37 (6): 1195–1199. doi:10.3899/jrheum.090625. PMID 20436080. S2CID 45438826.

- Geirsson AJ, Eyjolfsdottir H, Bjornsdottir G, Kristjansson K, Gudbjornsson B (May 2010). “Prevalence and clinical characteristics of ankylosing spondylitis in Iceland – a nationwide study”. Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology. 28 (3): 333–40. PMID 20406616.

Numerous cases during World Wars I and II focused attention on the triad of arthritis, urethritis, and conjunctivitis (often with additional mucocutaneous lesions), which at that time was also referred to as Fiessenger–Leroy–Reiter syndrome.

- Harrison’s Rheumatology, Second Edition [Anthony Fauci, Carol Langford], Ch.9 THE SPONDYLOARTHRITIDES, Reactive Arthritis, page.134

Signs and symptoms

- Because common systems involved include the eye, the urinary system, and the hands and feet, one clinical mnemonic in reactive arthritis is “Can’t see, can’t pee, can’t climb a tree.”

- Mark A. Marinella (1 September 2001). Recognizing Clinical Patterns: Clues to a Timely Diagnosis. Hanley & Belfus. p. 44. ISBN 978-1-56053-485-3.

- The classic triad consists of:

- Conjunctivitis

- Nongonococcal urethritis

- Asymmetric oligoarthritis

- Symptoms generally appear within 1–3 weeks but can range from 4 to 35 days from the onset of the inciting episode of the disease.

- The classical presentation of the syndrome starts with urinary symptoms such as burning pain on urination (dysuria) or an increased frequency of urination. Other urogenital problems may arise such as prostatitis in men and cervicitis, salpingitis and/or vulvovaginitis in women.

- It presents with monoarthritis affecting the large joints such as the knees and sacroiliac spine causing pain and swelling. An asymmetrical inflammatory arthritis of interphalangeal joints may be present but with relative sparing of small joints such as the wrist and hand.

- Patient can have enthesitis presenting as heel pain, Achilles tendinitis or plantar fasciitis, along with balanitis circinata (circinate balanitis), which involves penile lesions present in roughly 20 to 40 percent of the men with the disease.

- A small percentage of men and women develop small hard nodules called keratoderma blennorrhagicum on the soles of the feet and, less commonly, on the palms of the hands or elsewhere. The presence of keratoderma blennorrhagica is diagnostic of reactive arthritis in the absence of the classical triad. Subcutaneous nodules are also a feature of this disease.

- Ocular involvement (mild bilateral conjunctivitis) occurs in about 50% of men with urogenital reactive arthritis syndrome and about 75% of men with enteric reactive arthritis syndrome. Conjunctivitis and uveitis can include redness of the eyes, eye pain and irritation, or blurred vision. Eye involvement typically occurs early in the course of reactive arthritis, and symptoms may come and go.

- Dactylitis, or “sausage digit”, a diffuse swelling of a solitary finger or toe, is a distinctive feature of reactive arthritis and other peripheral spondylarthritides but can also be seen in polyarticular gout and sarcoidosis.

- Mucocutaneous lesions can be present. Common findings include oral ulcers that come and go. In some cases, these ulcers are painless and go unnoticed. In the oral cavity, the patients may experience recurrent aphthous stomatitis, geographic tongue and migratory stomatitis in higher prevalence than the general population.

- Zadik Y, Drucker S, Pallmon S (August 2011). “Migratory stomatitis (ectopic geographic tongue) on the floor of the mouth”. J Am Acad Dermatol. 65 (2): 459–60. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.04.016. PMID 21763590.

- Some patients experience serious gastrointestinal problems similar to those of Crohn’s disease.

- About 10 percent of people with reactive arthritis, especially those with a prolonged course of the disease, will develop cardiac manifestations, including aortic regurgitation and pericarditis. Reactive arthritis has been described as a precursor of other joint conditions, including ankylosing spondylitis.

Causes

See also: List of human leukocyte antigen alleles associated with cutaneous conditions

Reactive arthritis is associated with the HLA-B27 gene on chromosome 6 and by the presence of enthesitis as the basic pathologic lesion and is triggered by a preceding infection. The most common triggering infection in the US is a genital infection with Chlamydia trachomatis. Other bacteria known to cause reactive arthritis which are more common worldwide are Ureaplasma urealyticum, Salmonella spp., Shigella spp., Yersinia spp., and Campylobacter spp. A bout of food poisoning or a gastrointestinal infection may also precede the disease (the last four genera of bacteria mentioned above are enteric bacteria). Shigella is the most common organism causing reactive arthritis following diarrhea. Chlamydia trachomatis is the most common cause of reactive arthritis following urethritis. Ureaplasma and mycoplasma are rare causes. There is some circumstantial evidence for other organisms causing the disease, but the details are unclear.

- Kataria, RK; Brent LH (June 2004). “Spondyloarthropathies”. American Family Physician. 69 (12): 2853–2860. PMID 15222650. Archived from the original on 9 July 2008. Retrieved 16 June 2013.

- Hill Gaston JS, Lillicrap MS (2003). “Arthritis associated with enteric infection”. Best Pract Ice & Research. Clinical Rheumatology. 17 (2): 219–239. doi:10.1016/S1521-6942(02)00104-3. PMID 12787523.

- Paget, Stephen (2000). Manual of Rheumatology and Outpatient Orthopedic Disorders: Diagnosis and Therapy (4th ed.). Lippincott, Williams, & Wilkins. pp. chapter 36. ISBN 978-0-7817-1576-8.

Reactive arthritis usually manifests about 1–3 weeks after a known infection. The mechanism of interaction between the infecting organism and the host is unknown. Synovial fluid cultures are negative, suggesting that reactive arthritis is caused either by an autoimmune response involving cross-reactivity of bacterial antigens with joint tissues or by bacterial antigens that have somehow become deposited in the joints.[citation needed]

(HLA) B27

Human leukocyte antigen (HLA) B27 (subtypes B*2701-2759) is a class I surface molecule encoded by the B locus in the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) on chromosome 6 and presents antigenic peptides (derived from self and non-self antigens) to T cells. HLA-B27 is strongly associated with ankylosing spondylitis and other associated inflammatory diseases, such as psoriatic arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, and reactive arthritis.

- M. A. Khan (2010). “HLA and spondyloarthropathies”. In Narinder K. Mehra (ed.). The HLA Complex in Biology and Medicine. New Delhi, India: Jayppee Brothers Medical Publishers. pp. 259–275. ISBN 978-81-8448-870-8.

Prevalence

The prevalence of HLA-B27 varies markedly in the global population. For example, about 8% of Caucasians, 4% of North Africans, 2–9% of Chinese, and 0.1–0.5% of persons of Japanese descent possess the gene that codes for this antigen. Among the Sami in Northern Scandinavia (Sápmi), 24% of people are HLA-B27 positive, while 1.8% have associated ankylosing spondylitis, compared to 14-16% of Northern Scandinavians in general. In Finland, an estimated 14% of the population is positive for HLA-B27, while over 95% of patients with ankylosing spondylitis and approximately 70–80% of patients with Reiter’s disease or reactive arthritis have the genetic marker.

- M. A. Khan (2010). “HLA and spondyloarthropathies”. In Narinder K. Mehra (ed.). The HLA Complex in Biology and Medicine. New Delhi, India: Jayppee Brothers Medical Publishers. pp. 259–275. ISBN 978-81-8448-870-8.

- Johnsen, K.; Gran, J. T.; Dale, K.; Husby, G. (October 1992). “The prevalence of ankylosing spondylitis among Norwegian Samis (Lapps)”. The Journal of Rheumatology. 19 (10): 1591–1594. ISSN 0315-162X. PMID 1464873.

- Gran, J. T.; Mellby, A. S.; Husby, G. (January 1984). “The Prevalence of HLA-B27 in Northern Norway”. Scandinavian Journal of Rheumatology. 13 (2): 173–176. doi:10.3109/03009748409100382. ISSN 0300-9742.

- Bjelle, Anders; Cedergren, Bertil; Rantapää Dahlqvist, Solbritt (January 1982). “HLA B 27 in the Population of Northern Sweden”. Scandinavian Journal of Rheumatology. 11 (1): 23–26. doi:10.3109/03009748209098109. ISSN 0300-9742.

- “Vaasa, laboratorio-ohjekirja Ly-Kudosantigeeni B27 (Vaasa, laboratory manual Ly-Tissue antigen B27)” (in Finnish). 2014-07-21. Retrieved 2023-04-13.

Disease associations

The relationship between HLA-B27 and many diseases has not yet been fully elucidated. Though HLA-B27 is associated with a wide range of pathology, it does not appear to be the sole mediator in development of disease. In particular, 90% of people with ankylosing spondylitis (AS) are HLA-B27 positive, though only a small fraction of people with HLA-B27 ever develop AS. People who are HLA-B27 positive are also more likely to experience early onset AS than HLA-B27 negative individuals. There are additional genes being discovered that also predispose to AS and associated diseases, and additionally there are potential environmental factors (triggers) that may also play a role in susceptible individuals.

- Feldtkeller, Ernst; Khan, Muhammad; van der Heijde, Désirée; van der Linden, Sjef; Braun, Jürgen (March 2003). “Age at disease onset and diagnosis delay in HLA-B27 negative vs. positive patients with ankylosing spondylitis”. Rheumatology International. 23 (2): 61–66. doi:10.1007/s00296-002-0237-4. PMID 12634937. S2CID 6020403.

- Thomas, Gethin P.; Brown, Matthew A. (January 2010). “Genetics and genomics of ankylosing spondylitis”. Immunological Reviews. 233 (1): 162–180. doi:10.1111/j.0105-2896.2009.00852.x. PMID 20192999. S2CID 205223192.

- M. A. Khan (2010). “HLA and spondyloarthropathies”. In Narinder K. Mehra (ed.). The HLA Complex in Biology and Medicine. New Delhi, India: Jayppee Brothers Medical Publishers. pp. 259–275. ISBN 978-81-8448-870-8.

In addition to its association with ankylosing spondylitis, HLA-B27 is implicated in other types of seronegative spondyloarthropathy as well, such as reactive arthritis, certain eye disorders such as acute anterior uveitis and iritis, psoriatic arthritis, Crohn’s and ulcerative colitis associated spondyloarthritis. The shared association with HLA-B27 leads to increased clustering of these diseases. HLA antigens have also been studied in relation to autism.

- Elizabeth D Agabegi; Agabegi, Steven S. (2008). Step-Up to Medicine (Step-Up Series). Hagerstwon, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-7817-7153-5.

- Kataria, RK; Brent LH (June 2004). “Spondyloarthropathies”. American Family Physician. 69 (12): 2853–2860. PMID 15222650. Archived from the original on 2008-07-09. Retrieved 2009-06-29.

- Torres, Anthony; Jonna Westover (February 2012). “HLA Immune Function Genes in Autism”. Autism Research and Treatment. 2012 (12): 2853–2860. doi:10.1155/2012/959073. PMC 3420779. PMID 22928105.

Pathological mechanism

HLA-B27 is the most researched HLA-B allele due to its high relationship with spondyloarthropathies. Although it is not totally apparent how HLA-B27 promotes disease, there are some prominent views. The theories can be divided between antigen-dependent and antigen-independent categories.

- Hacquard-Bouder, Cécile; Ittah, Marc; Breban, Maxime (March 2006). “Animal models of HLA-B27-associated diseases: new outcomes”. Joint Bone Spine. 73 (2): 132–138. doi:10.1016/j.jbspin.2005.03.016. PMID 16377230.

Antigen-dependent theories

These theories consider a specific combination of antigen peptide sequence and the binding groove (B pocket) of HLA-B27 (which will have different properties from the other HLA-B alleles). The arthritogenic peptide hypothesis suggests that HLA-B27 has a unique ability to bind antigens from a microorganism that trigger a CD8 T-cell response that then cross-reacts with a HLA-B27/self-peptide pair. Furthermore, it has been shown that HLA-B27 can bind peptides at the cell surface. The molecular mimicry hypothesis is similar, however it suggests that cross reactivity between some bacterial antigens and self peptide can break tolerance and lead to autoimmunity.

- Hacquard-Bouder, Cécile; Ittah, Marc; Breban, Maxime (March 2006). “Animal models of HLA-B27-associated diseases: new outcomes”. Joint Bone Spine. 73 (2): 132–138. doi:10.1016/j.jbspin.2005.03.016. PMID 16377230.

- Bowness, Paul (21 March 2015). “HLA-B27”. Annual Review of Immunology. 33 (1): 29–48. doi:10.1146/annurev-immunol-032414-112110. PMID 25861975.

Antigen-independent theories

These theories refer to the unusual biochemical properties that HLA-B27 has. The misfolding hypothesis suggests that slow folding during HLA-B27’s tertiary structure folding and association with β2 microglobulin causes the protein to be misfolded, therefore initiating the unfolded protein response (UPR)—a pro-inflammatory endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress response. However, although this mechanism has been demonstrated both in vitro and in animals, there is little evidence of its occurrence in human spondyloarthritis. Also, the HLA-B27 heavy chain homodimer formation hypothesis suggests that B27 heavy chains tend to dimerise and accumulate in the ER, once again, initiating the UPR. Alternatively, cell surface B27 heavy chains and dimers can bind to regulatory immune receptors such as members of the killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptor family, promoting the survival and differentiation of pro-inflammatory leukocytes in disease.

- Hacquard-Bouder, Cécile; Ittah, Marc; Breban, Maxime (March 2006). “Animal models of HLA-B27-associated diseases: new outcomes”. Joint Bone Spine. 73 (2): 132–138. doi:10.1016/j.jbspin.2005.03.016. PMID 16377230.

- Bowness, Paul (21 March 2015). “HLA-B27”. Annual Review of Immunology. 33 (1): 29–48. doi:10.1146/annurev-immunol-032414-112110. PMID 25861975.

One more misfolding theory, published in 2004, proposes that β2 microglobulin-free heavy chains of HLA-B27 undergo a facile conformational change in which the C-terminal end of domain 2 (consisting of a long helix) becomes subject to a helix-coil transition involving residues 169–181 of the heavy chain, owing to the conformational freedom newly experienced by domain 3 of the heavy chain when there is no longer any bound light chain (i.e., β2 microglobulin) and owing to the consequent rotation around the backbone dihedral angles of residues 167/168. The proposed conformational transition is thought to allow the newly-generated coiled region (incorporating residues ‘RRYLENGKETLQR’ which have also been found to be naturally bound to HLA-B27 as a 9-mer peptide) to bind to either the peptide-binding cleft of the same polypeptide chain (in an act of self-display) or to the cleft of another polypeptide chain (in an act of cross-display). Cross-display is proposed to lead to the formation of large, soluble, high molecular weight (HMW), degradation-resistant, long-surviving aggregates of the HLA-B27 heavy chain. Together with any homodimers formed either by cross-display or by a disulfide-linked homodimerization mechanism, it is proposed that such HMW aggregates survive on the cell surface without undergoing rapid degradation, and stimulate an immune response. Three previously noted features of HLA-B27, which distinguish it from other heavy chains, underlie the hypothesis: (1) HLA-B27 has been found to be bound to peptides longer than 9-mers, suggesting that the cleft can accommodate a longer polypeptide chain; (2) HLA-B27 has been found to itself contain a sequence that has also been actually discovered to be bound to HLA-B27, as an independent peptide; and (3) HLA-B27 heavy chains lacking β2 microglobulin have been seen on cell surfaces.[citation needed]

- Luthra-Guptasarma, Manni; Singh, Balvinder (24 September 2004). “HLA-B27 lacking associated β2-microglobulin rearranges to auto-display or cross-display residues 169-181: a novel molecular mechanism for spondyloarthropathies”. FEBS Letters. 575 (1–3): 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2004.08.037. PMID 15388324.

HIV long-term nonprogressors

Around 1 in 500 people infected with HIV are able to remain symptom-free for many years without medication, a group known as long-term nonprogressors. The presence of HLA-B27, as well as HLA-B5701, is significantly common among this group.

- “HIV+ Long-Term Non-Progressor Study”. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. June 23, 2010. Archived from the original on July 19, 2011. Retrieved July 5, 2011.

- Deeks, Steven G.; Walker, Bruce D. (September 2007). “Human Immunodeficiency Virus Controllers: Mechanisms of Durable Virus Control in the Absence of Antiretroviral Therapy”. Immunity. 27 (3): 406–416. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2007.08.010. PMID 17892849.

Diagnosis

There are few clinical symptoms, but the clinical picture is dominated by arthritis in one or more joints, resulting in pain, swelling, redness, and heat sensation in the affected areas.

The urethra, cervix and the throat may be swabbed in an attempt to culture the causative organisms. Cultures may also be carried out on urine and stool samples or on fluid obtained by arthrocentesis.

Tests for C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate are non-specific tests that can be done to corroborate the diagnosis of the syndrome. A blood test for the genetic marker HLA-B27 may also be performed. About 75 percent of all the patients with reactive arthritis have this gene.

Diagnostic criteria

Although there are no definitive criteria to diagnose the existence of reactive arthritis, the American College of Rheumatology has published sensitivity and specificity guidelines.

- American College of Rheumatology. “Arthritis and Rheumatism”. Retrieved 16 May 2011.

| Method of diagnosis | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Episode of arthritis of more than 1 month with urethritis and/or cervicitis | 84.3% | 98.2% |

| 2. Episode of arthritis of more than 1 month and either urethritis or cervicitis, or bilateral conjunctivitis | 85.5% | 96.4% |

| 3. Episode of arthritis, conjunctivitis, and urethritis | 50.6% | 98.8% |

| 4. Episode of arthritis of more than 1 month, conjunctivitis, and urethritis | 48.2% | 98.8% |

Treatment

The main goal of treatment is to identify and eradicate the underlying infectious source with the appropriate antibiotics if still present. Otherwise, treatment is symptomatic for each problem. Nonspecific urethritis may be treated with a short course of tetracycline. Analgesics, particularly NSAIDs, are used. Steroids, sulfasalazine and immunosuppressants may be needed for patients with severe reactive symptoms that do not respond to any other treatment. Local corticosteroids are useful in the case of iritis.[citation needed]

Prognosis

Reactive arthritis may be self-limiting, frequently recurring, chronic or progressive. Most patients have severe symptoms lasting a few weeks to six months. 15 to 50 percent of cases involve recurrent bouts of arthritis. Chronic arthritis or sacroiliitis occurs in 15–30 percent of cases. Repeated attacks over many years are common, and patients sometimes end up with chronic and disabling arthritis, heart disease, amyloid deposits, ankylosing spondylitis, immunoglobulin A nephropathy, cardiac conduction abnormalities, or aortitis with aortic regurgitation. However, most people with reactive arthritis can expect to live normal life spans and maintain a near-normal lifestyle with modest adaptations to protect the involved organs.

- eMedicine/Medscape (5 January 2010). “Reactive Arthritis”. Retrieved 16 May 2011.

Epidemiology

Because women may be underdiagnosed, the exact incidence of reactive arthritis is difficult to estimate. A few studies have been completed, though. In Norway between 1988 and 1990, the incidence was 4.6 cases per 100,000 for chlamydia-induced reactive arthritis and 5 cases per 100,000 for that induced by enteric bacteria. In 1978 in Finland, the annual incidence was found to be 43.6 per 100,000.

- Kvien, T.; Glennas, A.; Melby, K.; Granfors, K; et al. (1994). “Reactive arthritis: Incidence, triggering agents and clinical presentation”. Journal of Rheumatology. 21 (1): 115–22. PMID 8151565.

- Isomäki, H.; Raunio, J.; von Essen, R.; Hämeenkorpi, R. (1979). “Incidence of rheumatic diseases in Finland”. Scandinavian Journal of Rheumatology. 7 (3): 188–192. doi:10.3109/03009747809095652. PMID 310157.

History

When reactive arthritis appears in a triad that also includes ophthalmic and urogenital manifestations, the eponym “Reiter’s syndrome” is often applied; German physician Hans Conrad Julius Reiter described the condition in a soldier he treated during World War I.

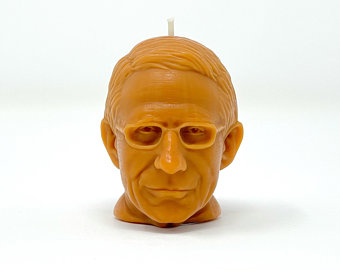

Hans Conrad Julius Reiter (26 February 1881 – 25 November 1969) was a German Nazi physician who conducted medical experiments at the Buchenwald concentration camp. He wrote a book on “racial hygiene” called Deutsches Gold, Gesundes Leben – Frohes Schaffen. In 1916, he described a disease with the symptoms urethritis, conjunctivitis and arthritis, which became known as Reiter’s syndrome.

- Wallace, DJ; Weisman, M (February 2000). “Should a war criminal be rewarded with eponymous distinction? The double life of Hans Reiter (1881–1969)”. Journal of Clinical Rheumatology. 6 (1): 49–54. doi:10.1097/00124743-200002000-00009. PMID 19078450.

- Deutsches gold, gesundes leben, frohes schaffen. OCLC 14742395.

Reiter was born in Reudnitz, near Leipzig in the German Empire. He studied medicine at Leipzig and Breslau (now Wrocław), and received a doctorate from Tübingen on the subject of tuberculosis. After receiving his doctorate, he went on to study at the hygiene institute in Berlin, the Pasteur Institute in Paris and St. Mary’s Hospital in London, where he worked with Sir Almroth Wright for two years. Reiter was also known for implementing strict anti-smoking laws in Nazi Germany.

- Good, Armin E. (1970). “Obituary – Hans Reiter, 1881–1969”. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 13 (3): 296–297. doi:10.1002/art.1780130313. hdl:2027.42/37714. PMID 4912634. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

First World War

During World War I, Reiter worked first as a German military physician on the Western Front in France. While there, he cared for several soldiers suffering from Weil’s disease, and made his first notable discovery that one of the causative bacteria were Leptospira icterohaemorrhagica, which had eluded culture methods and identification by other scientists ever since that disease had been recognized in 1886. Later, after being transferred to the Balkans, where he served in the 1st Hungarian Army, he reported a German lieutenant with non-gonococcal urethritis, arthritis, and uveitis that developed two days after a diarrheal illness and had a protracted course with relapses over several months. The combination of two of the elements, urethritis and arthritis, had been recognized in the 16th century, and the triad had first been reported by Sir Benjamin Collins Brodie, an English surgeon who lived from 1783 to 1862. Separately from Reiter, the triad was also reported in 1916 by Fiessinger and Leroy. Reiter thought he saw a spirochete which he called Treponema forans, related to but distinct from Treponema pallidum, the causative agent of syphilis, and erroneously thought it was the cause, calling the disease Spirochaetosis Arthritica. The error probably was influenced by his previous discovery of Leptospira icterohaemorrhagica, and by his work on Treponema pallidum that later enabled others to develop the “Reiter Complement Fixation Test” for syphilis. Nevertheless, the eponym Reiter’s syndrome was used for the disease he described, and the syndrome became widely known by that name.

- Good, Armin E. (1970). “Obituary – Hans Reiter, 1881–1969”. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 13 (3): 296–297. doi:10.1002/art.1780130313. hdl:2027.42/37714. PMID 4912634. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- Bailey, Hamilton; Bishop, W.J. (1959). “Reiter’s Disease”. British Journal of Venereal Diseases. 35 (2): 101–110. doi:10.1136/sti.35.2.101. PMC 1047253. PMID 13795839.

- Feissinger, Noel; Leroy, Edgar (1916). “Contribution à l’étude d’une épidémie dedysenterie dans la Somme”. Bulletins et Mémoires de la Société Médicale des Hôpitaux de Paris. 40: 2030–2069.

- Reiter, Hans (1916). “Über eine bisher unerkannte Spirochaeten infektion (Spirochaetosis Arthritica)”. Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift. 42 (50): 1535–1536. doi:10.1055/s-0028-1135542.

- Reiter, Hans (1917). “Über die Spirochaete forans”. Zentralblatt für Bakteriologie. 79: 176.

- Sommer, A. (1918). “Drei als wahrscheinlich Spirochaetosis Reiter arthritica anzusprechende Krankheitsfalle”. Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift. 44: 403. doi:10.1055/s-0028-1134378.

- Bauer, Walter; Engleman, Ephraim P. (1942). “A Syndrome of Unknown Etiology Characterized by Urethritis, Conjunctivitis and Arthritis (so-called Reiter’s Disease)”. Trans Assn Am Phys. 57: 307–313.

1918–1939

After the end of World War I, Reiter became chief of the hygiene department at Rostock. He was a political man, and an enthusiastic supporter of the Nazi regime. His career was further boosted when, in 1932, he signed an oath of allegiance to Adolf Hitler. In 1933, he was made department director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Experimental Therapy. In 1936, his meteoric rise continued when he was made director of the health department of Mecklenburg-Schwerin and received an honorary professorship in Berlin. With Johann Breger, he wrote a book on racial hygiene called Deutsches Gold, Gesundes Leben — Frohes Schaffen (“German Gold, Healthy Life — Glad Work”). He was also a strong supporter of Hitler’s anti-smoking campaign, considered medically progressive at the time. Reiter was a talented teacher who was popular with his students.

- Good, Armin E. (1970). “Obituary – Hans Reiter, 1881–1969”. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 13 (3): 296–297. doi:10.1002/art.1780130313. hdl:2027.42/37714. PMID 4912634. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

Second World War

Reiter was a member of the Schutzstaffel (SS) during World War II and participated in medical experiments performed by the Nazis. After the Nazis were defeated, he was arrested by the Red Army in Soviet Union-occupied Germany and tried at Nuremberg. During his detention, he admitted to knowledge of involuntary sterilization, euthanasia, and the murder of mental hospital patients in his function as the gatherer of statistics and acting as “quality control” officer, and to helping design and implement an explicitly criminal undertaking at Buchenwald concentration camp, in which internees were inoculated with an experimental typhus vaccine, resulting in over 200 deaths. He gained an early release from his internment, possibly because he assisted the Allies with his knowledge of germ warfare. After his release, Reiter went back to work in the field of medicine and research in rheumatology. He died at age 88, in 1969, at his country estate in Kassel-Wilhelmshöhe.

- Wallace, DJ; Weisman, M (February 2000). “Should a war criminal be rewarded with eponymous distinction?: the double life of hans reiter (1881–1969)”. Journal of Clinical Rheumatology. 6 (1): 49–54. doi:10.1097/00124743-200002000-00009. PMID 19078450.

- Deutsches gold, gesundes leben, frohes schaffen. OCLC 14742395.

- Good, Armin E. (1970). “Obituary – Hans Reiter, 1881–1969”. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 13 (3): 296–297. doi:10.1002/art.1780130313. hdl:2027.42/37714. PMID 4912634. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- Bailey, Hamilton; Bishop, W.J. (1959). “Reiter’s Disease”. British Journal of Venereal Diseases. 35 (2): 101–110. doi:10.1136/sti.35.2.101. PMC 1047253. PMID 13795839.

- Sampaio-Barros PD, Bortoluzzo AB, Conde RA, Costallat LT, Samara AM, Bértolo MB (June 2010). “Undifferentiated spondyloarthritis: a longterm followup”. The Journal of Rheumatology. 37 (6): 1195–1199. doi:10.3899/jrheum.090625. PMID 20436080. S2CID 45438826.

Reiter’s syndrome

In 1977, a group of doctors began a campaign to replace the term “Reiter’s syndrome” with “reactive arthritis“. In addition to Reiter’s war crimes, they pointed out that he was not the first to describe the syndrome, nor were his conclusions correct regarding its pathogenesis. Reiter incorrectly concluded that the triad of conjunctivitis, urethritis, and non-gonococcal arthritis was the result of a spirochetal infection and proposed the name “Spirochaetosis arthrosis”. The group of doctors was joined by Dr. Ephraim Engleman, one of the authors on the first English-language journal article that used the term “Reiter’s syndrome”, who was still practising 65 years later and had been unaware of Reiter’s Nazi connections at the time he suggested the eponym. The campaign gradually gained momentum, and the term “Reiter’s syndrome” has become increasingly anachronistic and has fallen out of favor.

- Altman, Lawrence (7 March 2000). “THE DOCTOR’S WORLD; Experts Re-examine Dr. Reiter, His Syndrome and His Nazi Past”. The New York Times. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

- Keynan, Y; Rimar, D (April 2008). “Reactive arthritis–the appropriate name”. The Israel Medical Association Journal (Review). 10 (4): 256–8. PMID 18548976.

- Panush, R.S.; Paraschiv, D.; Dorff, R.E. (February 2003). “The tainted legacy of Hans Reiter”. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 32 (4): 231–236. doi:10.1053/sarh.2003.49997. PMID 12621586.

- Panush, R.S.; Wallace, D.J.; Dorff, R.E.; Engleman, E.P. (2007). “Retraction of the suggestion to use the term “Reiter’s syndrome” sixty-five years later: the legacy of Reiter, a war criminal, should not be eponymic honor but rather condemnation”. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 56 (2): 693–694. doi:10.1002/art.22374. PMID 17265506.

- Wallace, D. J.; Weisman, M. (2000). “Should a war criminal be rewarded with eponymous distinction? The double life of Hans Reiter (1881–1969)”. JCR: Journal of Clinical Rheumatology. 6 (1): 49–54. doi:10.1097/00124743-200002000-00009. PMID 19078450.

A spirochaete or spirochete is a member of the phylum Spirochaetota (/-ˈkiːtiːz/), (synonym Spirochaetes) which contains distinctive diderm (double-membrane) gram-negative bacteria, most of which have long, helically coiled (corkscrew-shaped or spiraled, hence the name) cells. Spirochaetes are chemoheterotrophic in nature, with lengths between 3 and 500 μm and diameters around 0.09 to at least 3 μm. Spirochaetes are distinguished from other bacterial phyla by the location of their flagella, called endoflagella, or periplasmic flagella, which are sometimes called axial filaments. Endoflagella are anchored at each end (pole) of the bacterium within the periplasmic space (between the inner and outer membranes) where they project backwards to extend the length of the cell. These cause a twisting motion which allows the spirochaete to move about. When reproducing, a spirochaete will undergo asexual transverse binary fission. Most spirochaetes are free-living and anaerobic, but there are numerous exceptions. Spirochaete bacteria are diverse in their pathogenic capacity and the ecological niches that they inhabit, as well as molecular characteristics including guanine-cytosine content and genome size.

- “SPIROCHAETE | Meaning & Definition for UK English | Lexico.com”. Lexico Dictionaries | English. Archived from the original on 27 January 2021.

- Dorland’s Illustrated Medical Dictionary. Elsevier.

- Ryan KJ, Ray CG, eds. (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0-8385-8529-0.

- Margulis L, Ashen JB, Solé M, Guerrero R (August 1993). “Composite, large spirochetes from microbial mats: spirochete structure review”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 90 (15): 6966–6970. Bibcode:1993PNAS…90.6966M. doi:10.1073/pnas.90.15.6966. PMC 47056. PMID 8346204.

- Nakamura S (April 2020). “Spirochete Flagella and Motility”. Biomolecules. 10 (4): 550. doi:10.3390/biom10040550. PMC 7225975. PMID 32260454.

- Carroll KC, Hobden JA, Miller S (2019). “Spirochetes and Other Spiral Microorganisms”. Jawetz, Melnick, & Adelberg’s Medical Microbiology. McGraw-Hill Education. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- Madigan MT (2019). Brock biology of microorganisms (Fifteenth, Global ed.). NY, NY: Pearson. p. 519. ISBN 9781292235103.

- Paster BJ (2011). “Phylum XV. Spirochaetes Garrity and Holt.”. In Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Garrity GM, Staley JT (eds.). Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology. New York: Springer. p. 471.

Notable cases

- It has been postulated that Italian-born explorer Christopher Columbus had reactive arthritis, dying from a heart attack caused by the condition.

- “Cause of the death of Columbus (in Spanish)”. Eluniversal.com.mx. Archived from the original on 24 September 2014. Retrieved 29 July 2009.

- Pat Buchanan, American conservative political commentator, author, syndicated columnist, politician and broadcaster

- P. J. Gallagher

- Kelly, Fiach (4 January 2008). “Comedian reveals how he tracked birth parents to solve family health mystery”. Irish Independent. Retrieved 4 January 2008.

- Ian Murray, Scottish football player

- Lisa Gray (29 November 2006). “Murray targets Christmas as date for Rangers return”. The Independent.

- Mark St. John, one-time guitarist for Kiss

- Kirk Brandon, lead singer for Spear of Destiny

- Daniel Johns, Australian musician, lead singer for Silverchair

- “Silverchair frontman’s dramatic fight-back from crippling illness”. The Sydney Morning Herald. 1 December 2002. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- Steve Walters, football player and survivor of sexual abuse by football trainer Barry Bennell

- Daniel Taylor (22 November 2016). “Second footballer reveals abuse by serial paedophile Barry Bennell”. The Guardian.

See also

- List of medical eponyms with Nazi associations

- Dimples of Venus – Depressions over the gluteal fold

- Sacroiliac joint dysfunction – medical condition

- Surgery for the dysfunctional sacroiliac joint

- Piriformis syndrome – human medical condition affecting the sciatic nerve

- Ankylosing spondylitis – Type of arthritis in which there is long-term inflammation of the joints of the spine

- Human leukocyte antigen

References

- American College of Rheumatology. “Reactive Arthritis”. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- Mayo Staff (5 March 2011). “Reactive Arthritis (Reiter’s Syndrome)”. Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 16 May 2011.

- H. Hunter Handsfield (2001). Color atlas and synopsis of sexually transmitted diseases, Volume 236. McGraw-Hill Professional. p. 148. ISBN 978-0-07-026033-7.

- Primer on the Rheumatic Diseases, By John H. Klippel, page 218

- Rheumatology in Practice, By J. A. Pereira da Silva, Anthony D. Woolf page 5.9

- Ruddy, Shaun (2001). Kelley’s Textbook of Rheumatology, 6th Ed. W. B. Saunders. pp. 1055–1064. ISBN 978-0-7216-9033-9.

- Siala, Mariam; et al. (2008). “Analysis of bacterial DNA in synovial tissue of Tunisian patients with reactive and undifferentiated arthritis by broad-range PCR, cloning and sequencing”. Arthritis Research & Therapy. BioMed Central. 10 (2): R40. doi:10.1186/ar2398. PMC 2453759. PMID 18412942.

- Infectious Diseases Immunization Committee (1995). “Poststreptococcal arthritis”. The Canadian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 6 (3): 133–135. doi:10.1155/1995/470341. PMC 3327910. PMID 22514384.

- “Reactive Arthritis”. www.rheumatology.org. Retrieved 18 September 2019.

- Sampaio-Barros PD, Bortoluzzo AB, Conde RA, Costallat LT, Samara AM, Bértolo MB (June 2010). “Undifferentiated spondyloarthritis: a longterm followup”. The Journal of Rheumatology. 37 (6): 1195–1199. doi:10.3899/jrheum.090625. PMID 20436080. S2CID 45438826.

- Geirsson AJ, Eyjolfsdottir H, Bjornsdottir G, Kristjansson K, Gudbjornsson B (May 2010). “Prevalence and clinical characteristics of ankylosing spondylitis in Iceland – a nationwide study”. Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology. 28 (3): 333–40. PMID 20406616.

- Harrison’s Rheumatology, Second Edition [Anthony Fauci, Carol Langford], Ch.9 THE SPONDYLOARTHRITIDES, Reactive Arthritis, page.134

- Mark A. Marinella (1 September 2001). Recognizing Clinical Patterns: Clues to a Timely Diagnosis. Hanley & Belfus. p. 44. ISBN 978-1-56053-485-3.

- Zadik Y, Drucker S, Pallmon S (August 2011). “Migratory stomatitis (ectopic geographic tongue) on the floor of the mouth”. J Am Acad Dermatol. 65 (2): 459–60. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.04.016. PMID 21763590.

- Kataria, RK; Brent LH (June 2004). “Spondyloarthropathies”. American Family Physician. 69 (12): 2853–2860. PMID 15222650. Archived from the original on 9 July 2008. Retrieved 16 June 2013.

- Hill Gaston JS, Lillicrap MS (2003). “Arthritis associated with enteric infection”. Best Pract Ice & Research. Clinical Rheumatology. 17 (2): 219–239. doi:10.1016/S1521-6942(02)00104-3. PMID 12787523.

- Paget, Stephen (2000). Manual of Rheumatology and Outpatient Orthopedic Disorders: Diagnosis and Therapy (4th ed.). Lippincott, Williams, & Wilkins. pp. chapter 36. ISBN 978-0-7817-1576-8.

- American College of Rheumatology. “Arthritis and Rheumatism”. Retrieved 16 May 2011.

- eMedicine/Medscape (5 January 2010). “Reactive Arthritis”. Retrieved 16 May 2011.

- Kvien, T.; Glennas, A.; Melby, K.; Granfors, K; et al. (1994). “Reactive arthritis: Incidence, triggering agents and clinical presentation”. Journal of Rheumatology. 21 (1): 115–22. PMID 8151565.

- Isomäki, H.; Raunio, J.; von Essen, R.; Hämeenkorpi, R. (1979). “Incidence of rheumatic diseases in Finland”. Scandinavian Journal of Rheumatology. 7 (3): 188–192. doi:10.3109/03009747809095652. PMID 310157.

- Wallace, D. J.; Weisman, M. (2000). “Should a war criminal be rewarded with eponymous distinction? The double life of Hans Reiter (1881–1969)”. JCR: Journal of Clinical Rheumatology. 6 (1): 49–54. doi:10.1097/00124743-200002000-00009. PMID 19078450.

- “Cause of the death of Columbus (in Spanish)”. Eluniversal.com.mx. Archived from the original on 24 September 2014. Retrieved 29 July 2009.

- Kelly, Fiach (4 January 2008). “Comedian reveals how he tracked birth parents to solve family health mystery”. Irish Independent. Retrieved 4 January 2008.

- Lisa Gray (29 November 2006). “Murray targets Christmas as date for Rangers return”. The Independent.

- “Silverchair frontman’s dramatic fight-back from crippling illness”. The Sydney Morning Herald. 1 December 2002. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- Daniel Taylor (22 November 2016). “Second footballer reveals abuse by serial paedophile Barry Bennell”. The Guardian.

- M. A. Khan (2010). “HLA and spondyloarthropathies”. In Narinder K. Mehra (ed.). The HLA Complex in Biology and Medicine. New Delhi, India: Jayppee Brothers Medical Publishers. pp. 259–275. ISBN 978-81-8448-870-8.

- Johnsen, K.; Gran, J. T.; Dale, K.; Husby, G. (October 1992). “The prevalence of ankylosing spondylitis among Norwegian Samis (Lapps)”. The Journal of Rheumatology. 19 (10): 1591–1594. ISSN 0315-162X. PMID 1464873.

- Gran, J. T.; Mellby, A. S.; Husby, G. (January 1984). “The Prevalence of HLA-B27 in Northern Norway”. Scandinavian Journal of Rheumatology. 13 (2): 173–176. doi:10.3109/03009748409100382. ISSN 0300-9742.

- Bjelle, Anders; Cedergren, Bertil; Rantapää Dahlqvist, Solbritt (January 1982). “HLA B 27 in the Population of Northern Sweden”. Scandinavian Journal of Rheumatology. 11 (1): 23–26. doi:10.3109/03009748209098109. ISSN 0300-9742.

- “Vaasa, laboratorio-ohjekirja Ly-Kudosantigeeni B27 (Vaasa, laboratory manual Ly-Tissue antigen B27)” (in Finnish). 2014-07-21. Retrieved 2023-04-13.

- Feldtkeller, Ernst; Khan, Muhammad; van der Heijde, Désirée; van der Linden, Sjef; Braun, Jürgen (March 2003). “Age at disease onset and diagnosis delay in HLA-B27 negative vs. positive patients with ankylosing spondylitis”. Rheumatology International. 23 (2): 61–66. doi:10.1007/s00296-002-0237-4. PMID 12634937. S2CID 6020403.

- Thomas, Gethin P.; Brown, Matthew A. (January 2010). “Genetics and genomics of ankylosing spondylitis”. Immunological Reviews. 233 (1): 162–180. doi:10.1111/j.0105-2896.2009.00852.x. PMID 20192999. S2CID 205223192.

- Elizabeth D Agabegi; Agabegi, Steven S. (2008). Step-Up to Medicine (Step-Up Series). Hagerstwon, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0-7817-7153-5.

- Kataria, RK; Brent LH (June 2004). “Spondyloarthropathies”. American Family Physician. 69 (12): 2853–2860. PMID 15222650. Archived from the original on 2008-07-09. Retrieved 2009-06-29.

- Torres, Anthony; Jonna Westover (February 2012). “HLA Immune Function Genes in Autism”. Autism Research and Treatment. 2012 (12): 2853–2860. doi:10.1155/2012/959073. PMC 3420779. PMID 22928105.

- Hacquard-Bouder, Cécile; Ittah, Marc; Breban, Maxime (March 2006). “Animal models of HLA-B27-associated diseases: new outcomes”. Joint Bone Spine. 73 (2): 132–138. doi:10.1016/j.jbspin.2005.03.016. PMID 16377230.

- Bowness, Paul (21 March 2015). “HLA-B27”. Annual Review of Immunology. 33 (1): 29–48. doi:10.1146/annurev-immunol-032414-112110. PMID 25861975.

- Luthra-Guptasarma, Manni; Singh, Balvinder (24 September 2004). “HLA-B27 lacking associated β2-microglobulin rearranges to auto-display or cross-display residues 169-181: a novel molecular mechanism for spondyloarthropathies”. FEBS Letters. 575 (1–3): 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2004.08.037. PMID 15388324.

- “HIV+ Long-Term Non-Progressor Study”. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. June 23, 2010. Archived from the original on July 19, 2011. Retrieved July 5, 2011.

- Deeks, Steven G.; Walker, Bruce D. (September 2007). “Human Immunodeficiency Virus Controllers: Mechanisms of Durable Virus Control in the Absence of Antiretroviral Therapy”. Immunity. 27 (3): 406–416. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2007.08.010. PMID 17892849.

- Fiani B, Sekhon M, Doan T, Bowers B, Covarrubias C, Barthelmass M, De Stefano F, Kondilis A. Sacroiliac Joint and Pelvic Dysfunction Due to Symphysiolysis in Postpartum Women. Cureus. 2021 Oct 9;13(10):e18619. doi: 10.7759/cureus.18619. PMID: 34786225; PMCID: PMC8580107.

- Aldabe D, Ribeiro DC, Milosavljevic S, Dawn Bussey M. Pregnancy-related pelvic girdle pain and its relationship with relaxin levels during pregnancy: a systematic review. Eur Spine J. 2012 Sep;21(9):1769-76. doi: 10.1007/s00586-012-2162-x. Epub 2012 Feb 4. PMID: 22310881; PMCID: PMC3459115.

- Solonen, K. A. (1957). “The sacroiliac joint in the light of anatomical, roentgenological and clinical studies”. Acta Orthopaedica Scandinavica Supplementum. 27: 1–127. PMID 13478452.

- Vleeming, A.; Schuenke, M. D.; Masi, A. T.; Carreiro, J. E.; Danneels, L.; Willard, F. H. (2012). “The sacroiliac joint: An overview of its anatomy, function and potential clinical implications”. Journal of Anatomy. 221 (6): 537–67. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2012.01564.x. PMC 3512279. PMID 22994881.

- Bogduk, Nicolai “Clinical and Radiological Anatomy of the Lumbar Spine” Elsevier Health Sciences, 2022, p. 172.

- Kiapour, Ali (February 11, 2020). “Biomechanics of the Sacroiliac Joint: Anatomy, Function, Biomechanics, Sexual Dimorphism, and Causes of Pain”. International Journal of Spine Surgery. 14 (Suppl 1): S3–S13. doi:10.14444/6077. PMC 7041664. PMID 32123652.

- Schunke, Gustave Bernard (1938). “The anatomy and development of the sacro-iliac joint in man”. The Anatomical Record. 72 (3): 313–31. doi:10.1002/ar.1090720306. S2CID 84682320.

- Chapter 13: Sacroiliac Joint Injection, page 235 in: Blake A. Johnson, Peter S. Staats, F. Todd Wetzel and John M. Mathis (2004). Image-Guided Spine Interventions. Springer. ISBN 9780387403205. doi: 10.1007/b97485

- Walker, Joan M. (1986). “Age-Related Differences in the Human Sacroiliac Joint: A Histological Study; Implications for Therapy”. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 7 (6): 325–34. doi:10.2519/jospt.1986.7.6.325. PMID 18802258.

- Alderink, Gordon J. (1991). “The Sacroiliac Joint: Review of Anatomy, Mechanics, and Function”. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 13 (2): 71–84. doi:10.2519/jospt.1991.13.2.71. PMID 18796854.

- Weisl, H. (1954). “The Ligaments of the Sacro-Iliac Joint Examined with Particular Reference to Their Function”. Cells Tissues Organs. 20 (3): 201–13. doi:10.1159/000140900. PMID 13137770.

- Dontigny, R. L. (1985). “Function and pathomechanics of the sacroiliac joint. A review”. Physical Therapy. 65 (1): 35–44. doi:10.1093/ptj/65.1.35. PMID 3155567. S2CID 40558712.

- Cibulka MT; Delitto A & Erhard RE (1992). “Pain patterns in patients with and without sacroiliac joint dysfunction”. In Vleeming A; Mooney V; Snijders CJ & Dorman T (eds.). First Interdisciplinary World Conference on Low Back Pain and its Relation to the Sacroiliac Joint. pp. 363–70. OCLC 28057865.

- Fortin, J. D.; Falco, F. J. (1997). “The Fortin finger test: An indicator of sacroiliac pain”. American Journal of Orthopedics. 26 (7): 477–80. PMID 9247654.

- Sturesson, B; Selvik, G; Udén, A (1989). “Movements of the sacroiliac joints. A roentgen stereophotogrammetric analysis”. Spine. 14 (2): 162–5. doi:10.1097/00007632-198902000-00004. PMID 2922636. S2CID 10520615.

- Sturesson, B; Uden, A; Vleeming, A (2000). “A radiostereometric analysis of movements of the sacroiliac joints during the standing hip flexion test”. Spine. 25 (3): 364–8. doi:10.1097/00007632-200002010-00018. PMID 10703111. S2CID 33228238.

- Schwarzer, A. C.; Aprill, C. N.; Bogduk, N (1995). “The sacroiliac joint in chronic low back pain”. Spine. 20 (1): 31–7. doi:10.1097/00007632-199501000-00007. PMID 7709277. S2CID 45511167.

- Maigne, J. Y.; Boulahdour, H.; Chatellier, G. (1998). “Value of quantitative radionuclide bone scanning in the diagnosis of sacroiliac joint syndrome in 32 patients with low back pain”. European Spine Journal. 7 (4): 328–31. doi:10.1007/s005860050083. PMC 3611275. PMID 9765042.

- Maigne, J. Y.; Aivaliklis, A; Pfefer, F (1996). “Results of sacroiliac joint double block and value of sacroiliac pain provocation tests in 54 patients with low back pain”. Spine. 21 (16): 1889–92. doi:10.1097/00007632-199608150-00012. PMID 8875721. S2CID 25382636.

- Wallace, DJ; Weisman, M (February 2000). “Should a war criminal be rewarded with eponymous distinction?: the double life of hans reiter (1881–1969)”. Journal of Clinical Rheumatology. 6 (1): 49–54. doi:10.1097/00124743-200002000-00009. PMID 19078450.

- Deutsches gold, gesundes leben, frohes schaffen. OCLC 14742395.

- Good, Armin E. (1970). “Obituary – Hans Reiter, 1881–1969”. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 13 (3): 296–297. doi:10.1002/art.1780130313. hdl:2027.42/37714. PMID 4912634. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- Bailey, Hamilton; Bishop, W.J. (1959). “Reiter’s Disease”. British Journal of Venereal Diseases. 35 (2): 101–110. doi:10.1136/sti.35.2.101. PMC 1047253. PMID 13795839.

- Feissinger, Noel; Leroy, Edgar (1916). “Contribution à l’étude d’une épidémie dedysenterie dans la Somme”. Bulletins et Mémoires de la Société Médicale des Hôpitaux de Paris. 40: 2030–2069.

- Reiter, Hans (1916). “Über eine bisher unerkannte Spirochaeten infektion (Spirochaetosis Arthritica)”. Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift. 42 (50): 1535–1536. doi:10.1055/s-0028-1135542.

- Reiter, Hans (1917). “Über die Spirochaete forans”. Zentralblatt für Bakteriologie. 79: 176.

- Sommer, A. (1918). “Drei als wahrscheinlich Spirochaetosis Reiter arthritica anzusprechende Krankheitsfalle”. Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift. 44: 403. doi:10.1055/s-0028-1134378.

- Bauer, Walter; Engleman, Ephraim P. (1942). “A Syndrome of Unknown Etiology Characterized by Urethritis, Conjunctivitis and Arthritis (so-called Reiter’s Disease)”. Trans Assn Am Phys. 57: 307–313.

- Wallace, Daniel J.; Weisman, Michael (2003). “The physician Hans Reiter as prisoner of war in Nuremberg: a contextual review of his interrogation (1945–1947)”. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 32 (4): 208–230. doi:10.1053/sarh.2003.49995. PMID 12621585.

- Altman, Lawrence (7 March 2000). “THE DOCTOR’S WORLD; Experts Re-examine Dr. Reiter, His Syndrome and His Nazi Past”. The New York Times. Retrieved 28 July 2018.

- Keynan, Y; Rimar, D (April 2008). “Reactive arthritis–the appropriate name”. The Israel Medical Association Journal (Review). 10 (4): 256–8. PMID 18548976.

- Panush, R.S.; Paraschiv, D.; Dorff, R.E. (February 2003). “The tainted legacy of Hans Reiter”. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 32 (4): 231–236. doi:10.1053/sarh.2003.49997. PMID 12621586.

- Panush, R.S.; Wallace, D.J.; Dorff, R.E.; Engleman, E.P. (2007). “Retraction of the suggestion to use the term “Reiter’s syndrome” sixty-five years later: the legacy of Reiter, a war criminal, should not be eponymic honor but rather condemnation”. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 56 (2): 693–694. doi:10.1002/art.22374. PMID 17265506.

- “SPIROCHAETE | Meaning & Definition for UK English | Lexico.com”. Lexico Dictionaries | English. Archived from the original on 27 January 2021.

- Dorland’s Illustrated Medical Dictionary. Elsevier.

- Ryan KJ, Ray CG, eds. (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0-8385-8529-0.

- Margulis L, Ashen JB, Solé M, Guerrero R (August 1993). “Composite, large spirochetes from microbial mats: spirochete structure review”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 90 (15): 6966–6970. Bibcode:1993PNAS…90.6966M. doi:10.1073/pnas.90.15.6966. PMC 47056. PMID 8346204.

- Nakamura S (April 2020). “Spirochete Flagella and Motility”. Biomolecules. 10 (4): 550. doi:10.3390/biom10040550. PMC 7225975. PMID 32260454.

- Carroll KC, Hobden JA, Miller S (2019). “Spirochetes and Other Spiral Microorganisms”. Jawetz, Melnick, & Adelberg’s Medical Microbiology. McGraw-Hill Education. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- Madigan MT (2019). Brock biology of microorganisms (Fifteenth, Global ed.). NY, NY: Pearson. p. 519. ISBN 9781292235103.

- Paster BJ (2011). “Phylum XV. Spirochaetes Garrity and Holt.”. In Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Garrity GM, Staley JT (eds.). Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology. New York: Springer. p. 471.

- Paster BJ (2011). “Family I. Sprochaetes Swellengrebel 1907, 581AL.”. In Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Garrity GM, Staley JT (eds.). Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology. New York: Springer. pp. 473–531.

External links

| Classification | DICD–10: M02ICD–9-CM: 099.3MeSH: D016918DiseasesDB: 29524 |

|---|---|

| External resources | MedlinePlus: 000440eMedicine: med/1998Patient UK: Reactive arthritis |

- eMedicine

- Overview of Reactive Arthritis – US National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases

- HLA-B27 Syndromes at eMedicine by A. Luisa Di Lorenzo, MBBCh

- Bowness, P. (1 August 2002). “HLA B27 in health and disease: a double-edged sword?”. Rheumatology. 41 (8): 857–868. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/41.8.857. PMID 12154202.

- Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): 142830

- HLA-B27 at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- BASDAI and Ankylosing Spondylitis

- National Library of Medicine – Papers on HLA B-27

| Prokaryotes: Bacteria classification |

|---|

| Extant life phyla/divisions by domain |

|---|

Leave a Reply