The theca folliculi comprise a layer of the ovarian follicles. They appear as the follicles become secondary follicles.

The theca are divided into two layers, the theca interna and the theca externa.[1]

Theca cells are a group of endocrine cells in the ovary made up of connective tissue surrounding the follicle. They have many diverse functions, including promoting folliculogenesis and recruitment of a single follicle during ovulation.[2] Theca cells and granulosa cells together form the stroma of the ovary.

Androgen synthesis

Theca cells are responsible for synthesizing androgens, providing signal transduction between granulosa cells and oocytes during development by the establishment of a vascular system, providing nutrients, and providing structure and support to the follicle as it matures.[2]

Theca cells are responsible for the production of androstenedione, and indirectly the production of 17β estradiol, also called E2, by supplying the neighboring granulosa cells with androstenedione that with the help of the enzyme aromatase can be used as a substrate for this type of estradiol.[3] FSH induces the granulosa cells to synthesize aromatase, an enzyme that converts the androgens made by the theca interna into estradiol.[4]

Signaling cascade

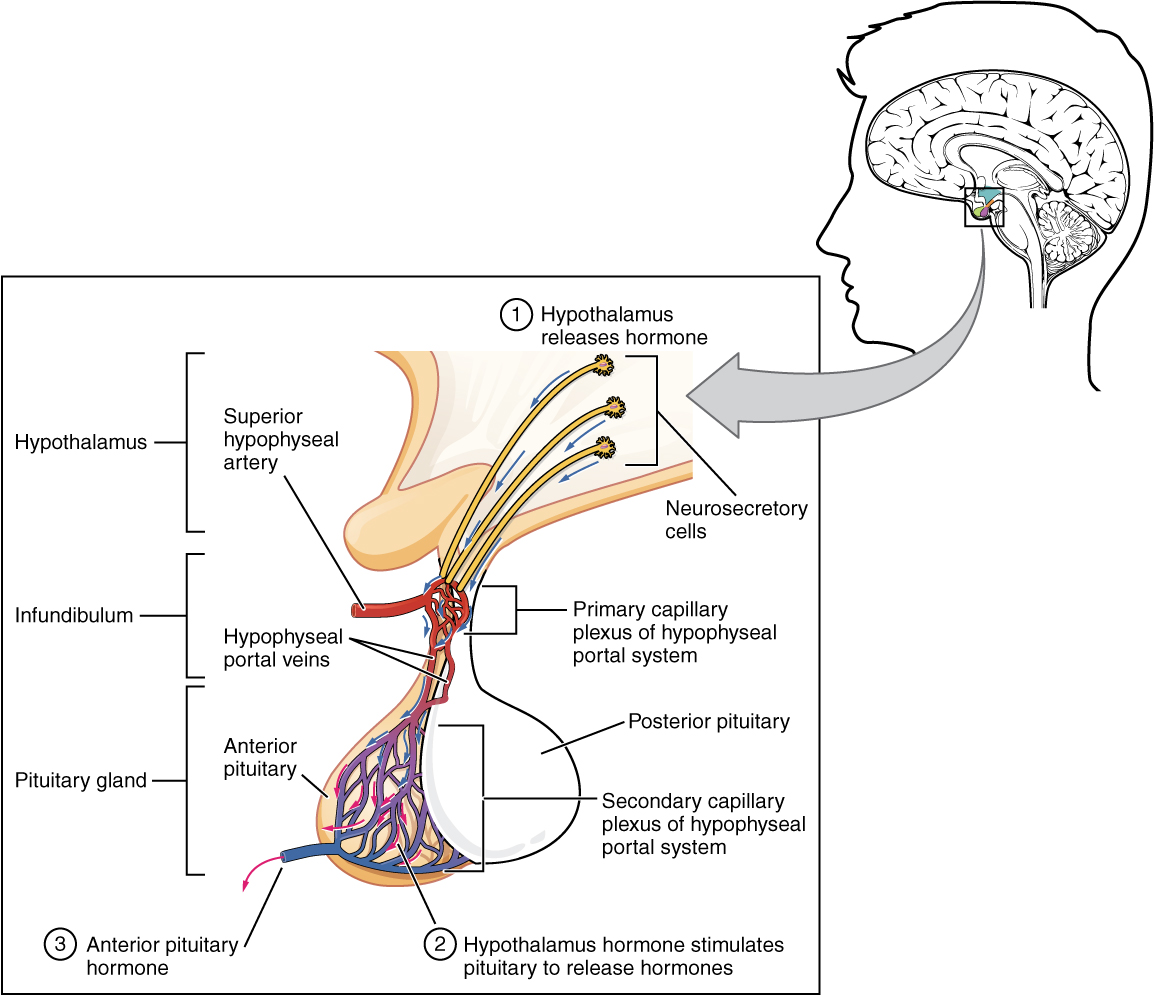

Gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) is released by projections of the hypothalamus into the anterior pituitary gland. Gonadotrophs are stimulated to produce follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH), which are released into the bloodstream to act upon the ovaries. Luteinizing hormone serves to directly stimulate theca cells. Together, these organs comprise the HPG axis.

Within the ovaries, transmembrane G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) bind to LH in the bloodstream, and the signal is transduced to the interior of theca cells through the action of the second messenger cAMP and third messenger protein kinase A (PKA). Theca cells are then stimulated to produce testosterone, which is sent in a paracrine fashion to neighboring granulosa cells for conversion to estradiol.[5]

Disorders

Hyperactivity of theca cells causes hyperandrogenism, and hypoactivity leads to a lack of estrogen.[6] Granulosa cell tumors, while rare (less than 5% of ovarian cancers), may both granulosa cells and theca cells.[7] Thecomas are benign proliferations of theca cells that may present with hormonal dysfunction.[8]

Theca cells (along with granulosa cells) form the corpus luteum during oocyte maturation. Theca cells are only correlated with developing ovarian follicles.[6] They are the leading cause of endocrine-based infertility, as either hyperactivity or hypoactivity of the theca cells can lead to fertility problems.

Folliculogenesis

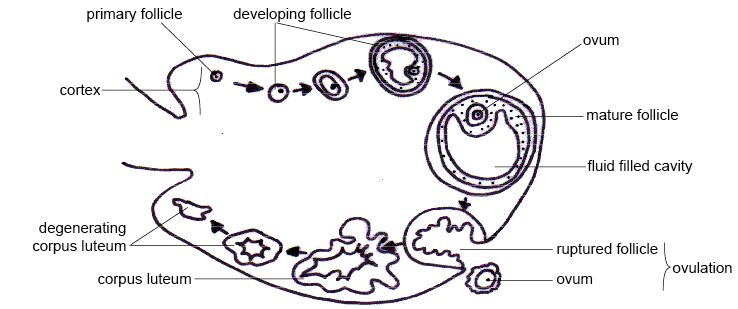

In human adult females, the primordial follicle is composed of a single oocyte surrounded by a layer of closely associated granulosa cells. In early stages of the ovarian cycle, the developing follicle acquires a layer of connective tissue and associated blood vessels. This covering is called the theca.

As development of the secondary follicle progresses, granulosa cells proliferate to form the multilayered membrana granulosum. Over a period of months, the granulosa cells and thecal cells secrete antral fluid (a mixture of hormones, enzymes, and anticoagulants) to nourish the maturing ovum.

In tertiary follicles, the single-layered theca differentiates into a theca interna and theca externa. The theca interna contains glandular cells and many small blood vessels, while the theca externa is composed of dense connective tissue and larger blood vessels.[9]

THECA EXTERNA

The theca externa is the outer layer of the theca folliculi. It is derived from connective tissue, the cells resembling fibroblasts, and contains abundant collagen.[10] During ovulation, the surge in luteinizing hormone increases cAMP which increases progesterone and PGF2α production. The PGF2α induces the contraction of the smooth muscle cells of the theca externa, increasing intrafollicular pressure. This aids in rupture of the mature oocyte, or immature oocyte at the germinal vesicle stage in the canine, along with plasmin and collagenase degradation of the follicle wall.

THECA INTERNA

Theca interna cells express receptors for luteinizing hormone (LH) to produce androstenedione, which via a few steps, gives the granulosa the precursor for estrogen manufacturing.[11]

After rupture of the mature ovarian follicle, the theca interna cells differentiate into the theca lutein cells of the corpus luteum. Theca lutein cells secrete androgens[12] and progesterone. Theca lutein cells are also known as small luteal cells.[12]

See also

- ovary

- theca

- thecoma

- polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS)

- dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS)

- luteinizing hormone (LH)

- follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH)

References

- Melmed, Shlomo; Koenig, Ronald; Rosen, Clifford; Auchus, Richard; Goldfine, Allison (2020). “17:Physiology and Pathology of the female reproductive axis”. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. Vol. 1: Section V:Sexual Development and Function (14th. ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 586–587. ISBN 978-8131262160.

- Young, J. M.; McNeilly, A. S. (2010). “Theca: the forgotten cell of the ovarian follicle”. Reproduction. 140 (4): 489–504. doi:10.1530/REP-10-0094. PMID 20628033.

- Hall, John E. (John Edward), 1946- (2015-05-20). Guyton and Hall textbook of medical physiology (13th ed.). Philadelphia, PA. p. 1042. ISBN 9781455770052. OCLC 900869748.

- Hall, John E. (John Edward), 1946- (2015-05-20). Guyton and Hall textbook of medical physiology (13th ed.). Philadelphia, PA. p. 1044. ISBN 9781455770052. OCLC 900869748.

- Medical physiology. Boron, Walter F.,, Boulpaep, Emile L. (Third ed.). Philadelphia, PA. 2016-03-29. ISBN 978-1-4557-3328-6. OCLC 951680737.

- Magoffin, Denis A. (2005). “Ovarian theca cell”. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology. 37 (7): 1344–9. doi:10.1016/j.biocel.2005.01.016. PMID 15833266.

- Kottarathil, Vijaykumar Dehannathparambil; Antony, Michelle Aline; Nair, Indu R.; Pavithran, Keechilat (2013). “Recent Advances in Granulosa Cell Tumor Ovary: A Review”. Indian Journal of Surgical Oncology. 4 (1): 37–47. doi:10.1007/s13193-012-0201-z. PMC 3578540. PMID 24426698.

- Burandt, Eike; Young, Robert H. (August 2014). “Thecoma of the ovary: a report of 70 cases emphasizing aspects of its histopathology different from those often portrayed and its differential diagnosis”. The American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 38 (8): 1023–1032. doi:10.1097/PAS.0000000000000252. ISSN 1532-0979. PMID 25025365. S2CID 10739300.

- Jones, Richard E. (Richard Evan), 1940- (2006). Human reproductive biology. Lopez, Kristin H. (3rd ed.). Amsterdam: Elsevier Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-088465-0. OCLC 61351645.

- Sadler, T. W. (2008). Langmans embryologi (2. ed.). Copenhagen: Munksgaard Danmark. p. 33. ISBN 9788762805088.

- Takei, Yoshio; Ando, Hironori; Tsutsui, Kazuyoshi (2016). “Subchapter 94G – Estradiol-17β”. Handbook of hormones: comparative endocrinology for basic and clinical research. Nihon Hikaku Naibunpi Gakkai (1st ed.). Oxford: Elsevier, Academic Press. pp. 520–522. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-801028-0.00226-9. ISBN 978-0-12-801028-0.

- The IUPS Physiome Project –> Female Reproductive System – Cells Archived December 10, 2009, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on Nov 9, 2009

External links

- Histology image: 14805loa – Histology Learning System at Boston University

- Anatomy photo: Reproductive/mammal/ovary2/ovary5 – Comparative Organology at University of California, Davis – “Mammal, canine ovary (LM, High)”

- Anatomy photo: Reproductive/mammal/ovary5/ovary6 – Comparative Organology at University of California, Davis – “Mammal, bovine ovary (LM, Medium)”

- UIUC Histology Subject 372 – interna

- UIUC Histology Subject 373 – externa

- Anatomy Atlases – Microscopic Anatomy, plate 13.249

- Slide at trinity.edu