In the ancient Levant, doves were used as symbols for the Canaanite mother goddess Asherah.

- Botterweck, G. Johannes; Ringgren, Helmer (1990). Theological Dictionary of the Old Testament. Vol. VI. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. pp. 35–36. ISBN 0-8028-2330-0.

- Lewis, Sian; Llewellyn-Jones, Lloyd (2018). The Culture of Animals in Antiquity: A Sourcebook with Commentaries. New York City, New York and London, England: Routledge. p. 335. ISBN 978-1-315-20160-3.

- The Enduring Symbolism of Doves, From Ancient Icon to Biblical Mainstay by Dorothy D. Resig BAR Magazine Archived 31 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Bib-arch.org (9 February 2013). Retrieved on 5 March 2013.

The Canaanite religion was the group of ancient Semitic religions practiced by the Canaanites living in the ancient Levant from at least the early Bronze Age through the first centuries AD. Canaanite religion was polytheistic and, in some cases, monolatristic. Some gods and goddesses were absorbed into the Yahwist religion of the ancient Israelites, notably El (who later became synonymous with Yahweh), Baal and Asherah, until the Babylonian captivity where they worshipped Yahweh alone.

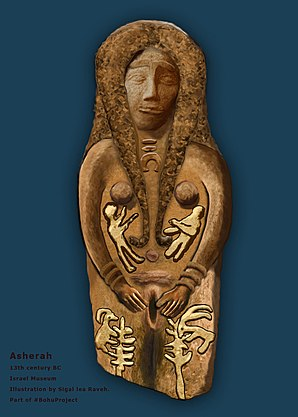

Asherah (Hebrew: אֲשֵׁרָה, romanized: Ăšērā; Ugaritic: 𐎀𐎘𐎗𐎚, romanized: ʾAṯiratu; Akkadian: 𒀀𒅆𒋥, romanized: Aširat; Qatabanian: 𐩱𐩻𐩧𐩩 ʾṯrt) in ancient Semitic religion, is a fertility goddess who appears in a number of ancient sources. She also appears in Hittite writings as Ašerdu(s) or Ašertu(s) (Hittite: 𒀀𒊺𒅕𒌈, romanized: a-še-ir-tu4). Her name is sometimes rendered Athirat in the context of her cult at Ugarit.

- “Asherah”. The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia. Columbia University Press. 2022. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- Day, John. “Asherah in the Hebrew Bible and Northwest Semitic Literature.” Journal of Biblical Literature, vol. 105, no. 3, 1986, pp. 385–408. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3260509. Accessed 5 Aug. 2021.

- “DASI: Digital Archive for the Study of pre-islamic arabian Inscriptions: Word list occurrences”. dasi.cnr.it. Archived from the original on 6 August 2021. Retrieved 6 August 2021.

- ‘Asertu, tablet concordance KUB XXXVI 35 – CTH 342 Archived 5 August 2021 at the Wayback Machine‘, Hittite Collection, Hatice Gonnet-Bağana; Koç University.

Significance and roles

Asherah is identified as the consort of the Sumerian god Anu, and Ugaritic ʾEl, the oldest deities of their respective pantheons. This role gave her a similarly high rank in the Ugaritic pantheon. Deuteronomy 12 has Yahweh commanding the destruction of her shrines so as to maintain purity of his worship. The name Dione, which like ʾElat means “goddess”, is clearly associated with Asherah in the Phoenician History of Sanchuniathon, because the same common epithet (ʾElat) of “the Goddess par excellence” was used to describe her at Ugarit. The Book of Jeremiah, written circa 628 BC, possibly refers to Asherah when it uses the title “queen of heaven“[a] in Jeremiah 7:16–18 and Jeremiah 44:17–19, 25.

- [a] Hebrew: מְלֶכֶת הַשָּׁמַיִם

- “Asherah” in The New Encyclopædia Britannica. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 15th edn., 1992, Vol. 1, pp. 623–624.

- Leeming, David (17 November 2005). The Oxford Companion to World Mythology. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-19-515669-0. Archived from the original on 26 February 2022. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- Binger, Tilde (1997). Asherah: Goddesses in Ugarit, Israel and the Old Testament (1st ed.). Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press. pp. 74. ISBN 9780567119766.

- Deuteronomy 12: 3–4

- Olyan, Saul M. (1988), Asherah and the cult of Yahweh in Israel, Scholars Press, p. 79, ISBN 9781555402549

- “…pray thou not for this people… The children gather wood, and the fathers kindle the fire, and the women knead [their] dough, to make cakes to the queen of heaven, and to pour out drink offerings to other gods, that they may provoke me to anger.” (King James Version)

- Rainer, Albertz (2010), “Personal piety”, in Stavrakopoulou, Francesca; Barton, John (eds.), Religious Diversity in Ancient Israel and Judah (reprint ed.), Continuum International Publishing Group, pp. 135–146 (at 143), ISBN 9780567032164

In Eastern Semitic texts

In Ugaritic texts, Asherah appears as ʾAṯirat (Ugaritic: 𐎀𐎘𐎗𐎚), anglicised Athirat. Sources from before 1200 BC almost always credit Athirat with her full title rbt ʾṯrt ym (or rbt ʾṯrt).[b] The phrase occurs 12 times in the Baʿal Epic alone.

- Gibson, J. C. L.; Driver, G. R. (1978), Canaanite Myths and Legends, T. & T. Clark, ISBN 9780567023513

- [b] Ugaritic 𐎗𐎁𐎚 𐎀𐎘𐎗𐎚 𐎊𐎎, rbt ʾṯrt ym

The title rbt is most often vocalised as rabītu, although rabat and rabīti are sometimes used by scholars. Apparently of Akkadian origin, rabītu means “lady” (literally “female great one”). She appears to champion her son, Yam, god of the sea, in his struggle against Baʾal. Yam’s ascription as god of the sea in the English translation is somewhat misleading, however, as yām (Hebrew: יָם) is a common western Semitic root that literally means “sea”. Consequently, one should understand Yam to be the deified sea itself rather than a deity who holds dominion over it. Athirat’s title can therefore been translated as “Lady ʾAṯirat of the Sea”, alternatively, “she who walks on the sea”, or even “the Great Lady-who-tramples-Yam”. A suggestion in 2010 by a scholar is that the name Athirat might be derived from a passive participle form, referring to the “one followed by (the gods)”, that is, “pro-genitress or originatress”, which would correspond to Asherah’s image as the “mother of the gods” in Ugaritic literature.

- Wiggins, Steve A. (2007). Wyatt, N. (ed.). A Reassessment of Asherah: With Further Considerations of the Goddess. Gorgias Ugaritic Studies 2. NJ, USA: Gorgias Press. p. 77.

- Ahlström, Gösta W. (1963). Engnell, Ivan; Furumark, Arne; Nordström, Carl-Otto (eds.). Aspects of Syncretism in Israelite Religion. Horae Soederblominae 5. Translated by Sharpe, Eric J. Lund, SE: C.W.K. Gleerup. p. 68.

- Rahmouni, Aicha (2008). “Epithet 94: rbt ʾaṯrt ym”. Divine Epithets in the Ugaritic Alphabetic Texts. Translated by Ford, J. N. Leiden, NE: Brill. pp. 278. ISBN 9789004157699.

- Rahmouni, Aicha (2008). “Epithet 94: rbt ʾaṯrt ym”. Divine Epithets in the Ugaritic Alphabetic Texts. Translated by Ford, J. N. Leiden, NE: Brill. pp. 281. ISBN 9789004157699.

- Binger, Tilde (1997). Asherah: Goddesses in Ugarit, Israel and the Old Testament (1st ed.). Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press. pp. 44. ISBN 9780567119766.

- Wyatt, N. (2003). Religious Texts from Ugarit (2nd ed.). London: Sheffield Academic Press. pp. 131 et al.

- Sung Jin Park, “Short Notes on the Etymology of Asherah”, Ugarit Forschungen 42 (2010): 527–534.

Certain translators and commentators theorise that Athirat’s name is from the Ugaritic root ʾaṯr, “to stride”, a cognate of the Hebrew root ʾšr, of the same meaning. Alternative translations of her title have been tendered that follow this suggested etymology, such as “she who treads on the sea dragon”, or “she who treads on Tyre“—the former of which appears to be an attempt to grant the Ugaritic texts a type of Chaoskampf (struggle against Chaos). A more recent analysis of this epithet has resulted in the proposition of a radically different translation, namely “Lady Asherah of the day”, or, more simply, “Lady Day”. The common Semitic root ywm (for reconstructed Proto-Semitic *yawm-), from which derives (Hebrew: יוֹם), meaning “day”, appears in several instances in the Masoretic Texts with the second-root letter (–w–) having been dropped, and in a select few cases, replaced with an A-class vowel of the Niqqud, resulting in the word becoming y(a)m. Such occurrences, as well as the fact that the plural, “days”, can be read as both yōmîm and yāmîm (Hebrew: יָמִים), gives credence to this alternate translation.

- Albright, W. F. (1968). Yahweh and the gods of Canaan: a historical analysis of two contrasting faiths. London: University of London, Athlone Press. pp. 105–106. ISBN 9780931464010.

- Emerton, J. A. (1982). “New Light on Israelite Religion: The Implications of the Inscriptions from Kuntillet ʿAjrud”, Zeitschrift für die Alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 94. Brill. p. 8. doi:10.1515/zatw.1982.94.1.2. S2CID 170614720.

- Binger, Tilde (1997). Asherah: Goddesses in Ugarit, Israel and the Old Testament (1st ed.). Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press. pp. 42–93. ISBN 9780567119766.

- Kogan, Leonid (2012). “Proto-Semitic Lexicon”. In Weninger, Stefan (ed.). The Semitic Languages: An International Handbook. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 179–258.

- Numbers 6:5, Job 7:6

Another primary epithet of Athirat was qnyt ʾilm,[c] which may be translated as “the creatrix of the deities“. In those texts, Athirat is the consort of the god ʾEl; there is one reference to the 70 sons of Athirat, presumably the same as the 70 sons of ʾEl. Among the Hittites this goddess appears as Ašerdu(s) or Ašertu(s), the consort of Elkunirsa (“El, the Creator of Earth“) and mother of either 77 or 88 sons. Within the Amarna letters is found reference to a king of the Amorites by the name of Abdi-Ashirta, “servant of Asherah”.

- [c] Ugaritic 𐎖𐎐𐎊𐎚 𐎛𐎍𐎎, qnyt ʾlm

- see KTU 1.4 I 23.

- Noted by Raphael Patai, “The Goddess Asherah”, Journal of Near Eastern Studies 24.1/2 (1965: 37–52), p. 39.

- Gibson, J. C. L.; Driver, G. R. (1978), Canaanite Myths and Legends, T. & T. Clark, ISBN 9780567023513

In the Ugaritic sources she is also called ʾElat,[d] “goddess“, the feminine form of ʾEl (compare Allāt); she is also called Qodeš, “holiness”,[e] in these sources.

- [d] Ugaritic 𐎛𐎍𐎚, ʾilt

- [e] Ugaritic 𐎖𐎄𐎌, qdš

In Akkadian texts, Asherah appears as Aširatu; though her exact role in the pantheon is unclear; as a separate goddess, Antu, was considered the wife of Anu, the god of Heaven. In contrast, ʿAshtart is believed to be linked to the Mesopotamian goddess Ishtar who is sometimes portrayed as the daughter of Anu while in Ugaritic myth, ʿAshtart is one of the daughters of ʾEl, the West Semitic counterpart of Anu. Several Akkadian sources also preserve what are considered to be Amorite theophoric names which use Asherah—usually appearing as Aširatu or Ašratu.

- Hess, Richard S. “Asherah or Asherata?” Orientalia, vol. 65, no. 3, 1996, pp. 209–219. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/43078131. Accessed 6 Aug. 2021.

In Egyptian sources

A digital collage showing an image of Qetesh together with hieroglyphs taken from a separate Egyptian relief (the “Triple Goddess stone”)

Beginning during the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt, a Semitic goddess named Qetesh (“holiness”, sometimes reconstructed as Qudshu) appears prominently. That dynasty follows expulsion of occupying foreigners from an intermediary period. Some think this deity is Athirat/Ashratu under her Ugaritic name. This Qetesh seems not to be either ʿAshtart or ʿAnat as both those goddesses appear under their own names and with quite different iconography, yet is called “Qudshu-Astarte-Anat” in at least one pictorial representation, aptly named the “Triple Goddess Stone”.

In the Persian, Hellenistic, and Roman periods in Egypt, however, there was a strong tendency of syncretism toward goddesses, and Athirat/Ashratum then seems to have disappeared, at least as a prominent goddess under a recognizable name.

Religious scholar Saul M. Olyan (author of Asherah and the Cult of Yahweh in Israel) calls the representation on the Qudshu-Astarte-Anat plaque “a triple-fusion hypostasis”, and considers Qudshu to be an epithet of Athirat by a process of elimination, for Astarte and Anat appear after Qudshu in the inscription.

- The Ugaritic Baal cycle: Volume 2 by Mark S. Smith, page 295

- The Origins of Biblical Monotheism: Israel’s Polytheistic Background and the Ugaritic Texts by Mark S. Smith – Page 237

In Israel and Judah

Between the tenth century BC and the beginning of their Babylonian exile in 586 BC, polytheism was normal throughout Israel. Worship solely of Yahweh became established only after the exile, and possibly, only as late as the time of the Maccabees (2nd century BC). That is when monotheism became universal among the Jews. Some biblical scholars believe that Asherah at one time was worshipped as the consort of Yahweh, the national god of Israel.

- Finkelstein, Israel, and Silberman, Neil Asher, The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology’s New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts, Simon & Schuster, 2002, pp. 241–242.

- “BBC Two – Bible’s Buried Secrets, Did God Have a Wife?”. BBC. 21 December 2011. Archived from the original on 15 January 2012. Retrieved 4 July 2012.

- Quote from the BBC documentary (prof. Herbert Niehr): “Between the 10th century and the beginning of their exile in 586 there was polytheism as normal religion all throughout Israel; only afterwards things begin to change and very slowly they begin to change. I would say it [the sentence “Jews were monotheists” – n.n.] is only correct for the last centuries, maybe only from the period of the Maccabees, that means the second century BC, so in the time of Jesus of Nazareth it is true, but for the time before it, it is not true.”

- Wesler, Kit W. (2012). An Archaeology of Religion. University Press of America. p. 193. ISBN 978-0761858454. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 3 September 2014.

- Mills, Watson, ed. (31 December 1999). Mercer Dictionary of the Bible (Reprint ed.). Mercer University Press. p. 494. ISBN 978-0865543737. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 5 November 2020.

There are references to the worship of numerous deities throughout the Books of Kings: Solomon builds temples to many deities and Josiah is reported as cutting down the statues of Asherah in the temple Solomon built for Yahweh (2 Kings 23:14). Josiah’s grandfather Manasseh had erected one such statue (2 Kings 21:7).

- “Genesis Chapter 1 (NKJV)”. Blue Letter Bible. Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

Further evidence for Asherah-worship includes, for example, an eighth-century BC combination of iconography and inscriptions discovered at Kuntillet Ajrud in the northern Sinai desert where a storage jar shows three anthropomorphic figures and several inscriptions. The inscriptions found refer not only to Yahweh but to ʾEl and Baʿal, and two include the phrases “Yahweh of Samaria and his Asherah” and “Yahweh of Teman and his Asherah.” The references to Samaria (capital of the kingdom of Israel) and Teman (in Edom) suggest that Yahweh had a temple in Samaria, while raising questions about the relationship between Yahweh and Kaus, the national god of Edom. The “asherah” in question is most likely a cultic object, although the relationship of this object (a stylised tree perhaps) to Yahweh and to the goddess Asherah, consort of ʾEl, is unclear. It has been suggested that the Israelites may have considered Asherah as the consort of Baʿal, due to the anti-Asherah ideology that was influenced by the Deuteronomistic Historians, at the later period of the kingdom. Also, it has been suggested by several scholars that there is a relationship between the position of the gəḇīrā in the royal court and the worship (orthodox or not) of Asherah. In a potsherd inscription of blessings from “Yahweh and his Asherah”, there appears a cow feeding its calf. Numerous Canaanite amulets depict a woman wearing a bouffant wig similar to the Egyptian Hathor. If Asherah is then to be associated with Hathor/Qudshu, it can then be assumed that the cow is being referred to as Asherah.

- Ze’ev Meshel, Kuntillet ‘Ajrud: An Israelite Religious Center in Northern Sinai Archived 29 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Expedition 20 (Summer 1978), pp. 50–55

- Dever 2005

- Hadley 2000, pp. 122–136

- Bonanno, Anthony (1986). Archaeology and Fertility Cult in the Ancient Mediterranean: Papers Presented at the First International Conference on Archaeology of the Ancient Mediterranean, University of Malta, 2–5 September 1985. John Benjamins Publishing. p. 238. ISBN 9789060322888. Archived from the original on 18 January 2022. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Keel, Othmar; Uehlinger, Christoph (1998). Gods, Goddesses, And Images of God. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 228. ISBN 9780567085917. Archived from the original on 15 June 2021. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Keel, Othmar; Uehlinger, Christoph (1998). Gods, Goddesses, And Images of God. Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 232–233. ISBN 9780567085917. Archived from the original on 15 June 2021. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Sung Jin Park, “The Cultic Identity of Asherah in Deuteronomistic Ideology of Israel,” Zeitschrift für die Alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 123/4 (2011): 553–564.

- Ackerman, Susan (1993). “The Queen Mother and the Cult in Ancient Israel”. Journal of Biblical Literature. 112 (3): 385–401. doi:10.2307/3267740. JSTOR 3267740.

- Bowen, Nancy (2001). “The Quest for the Historical Gĕbîrâ”. Catholic Biblical Quarterly. 64: 597–618.

- 1 Kings 15:13; 18:19, 2 Kings 10:13

- Dever 2005, p. 163.

William Dever’s book Did God Have a Wife? adduces further archaeological evidence—for instance, the many female figurines unearthed in ancient Israel, (known as pillar-base figurines)—as supporting the view that during Israelite folk religion of the monarchical period, Asherah functioned as a goddess and a consort of Yahweh and was worshiped as the queen of heaven, for whose festival the Hebrews baked small cakes. Dever also points to the discovery of multiple shrines and temples within ancient Israel and Judah. The temple site at Arad is particularly interesting for the presence of two (possibly three) massebot, standing stones representing the presence of deities. Although the identity of the deities associated with the massebot is uncertain, Yahweh and Asherah or Asherah and Baal remain strong candidates, as Dever notes: “The only goddess whose name is well attested in the Hebrew Bible (or in ancient Israel generally) is Asherah.”

The name Asherah appears forty times in the Hebrew Bible, but it is much reduced in English translations. The word ʾăšērâ is translated in Greek as Greek: ἄλσος (grove; plural: ἄλση) in every instance apart from Isaiah 17:8; 27:9 and 2 Chronicles 15:16; 24:18, with Greek: δένδρα (trees) being used for the former, and, peculiarly, Ἀστάρτη (Astarte) for the latter. The Vulgate in Latin provided lucus or nemus, a grove or a wood. From the Vulgate, the King James translation of the Bible uses grove or groves instead of Asherah’s name. Non-scholarly English language readers of the Bible would not have read her name for more than 400 years afterward.

- “Asherah”. www.asphodel-long.com. Archived from the original on 5 January 2006. Retrieved 14 February 2016.

The association of Asherah with trees in the Hebrew Bible is very strong. For example, she is found under trees (1 Kings 14:23; 2 Kings 17:10) and is made of wood by human beings (1 Kings 14:15, 2 Kings 16:3–4). Trees described as being an asherah or part of an asherah include grapevines, pomegranates, walnuts, myrtles, and willows.

- Danby, Herbert (1933). The Mishnah: Translated from the Hebrew With Introduction and Brief Explanatory Notes. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 90, 176. ISBN 9780198154020.

Worship and suppression

Episodes in the Hebrew Bible show a gender imbalance in Hebrew religion. Asherah was patronized by female royals such as the Queen Mother Maacah (1 Kings 15:13). But more commonly, perhaps, Asherah was worshiped within the household and her offerings were performed by family matriarchs. As the women of Jerusalem attested, “When we burned incense to the Queen of Heaven and poured out drink offerings to her, did not our husbands know that we were making cakes impressed with her image and pouring out drink offerings to her?” (Jeremiah 44:19). This passage corroborates a number of archaeological excavations showing altar spaces in Hebrew homes. The “household idols” variously referred to in the Bible may also be linked to the hundreds of female pillar-base figurines that have been discovered.

Jezebel brought hundreds of prophets for Baal and Asherah with her into the Israelite court.

- Coogan, Michael (2010). God and Sex. Twelve. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-446-54525-9.

Popular culture defines Canaanite religion and Hebrew idolatry as sexual “fertility cults,” products of primitive superstition rather than spiritual philosophy. This position is buttressed by the Hebrew Bible, which frequently and graphically associates goddess religions with prostitution. As Jeremiah wrote, “On every high hill and under every spreading tree you lay down as a prostitute” (Jeremiah 2:20). Hosea, Jeremiah, and Ezekiel in particular blame the goddess religions for making Yahweh “jealous”, and cite his jealousy as the reason Yahweh allowed the destruction of Jerusalem. As for sexual and fertility rites, it is likely that once they were held in honor in Israel, as they were throughout the ancient world. Although their nature remains uncertain, sexual rites typically revolved around women of power and influence, such as Maacah. The Hebrew term qadishtu, usually translated as “temple prostitutes” or “shrine prostitutes”, literally means “priestesses” or “priests”. However, there is a growing consensus that sacred prostitution never existed.

- Stone, Merlin (1976). When God Was A Woman: The landmark exploration of the ancient worship of the Great Goddess and the eventual suppression of women’s rites. ISBN 015696158X.

- Coogan 2010, p. 133.

Iconography

Some scholars have found an early link between Asherah and Eve, based upon the coincidence of their common title as “the mother of all living” in the Book of Genesis 3:20 through the identification with the Hurrian mother goddess Hebat. There is further speculation that the Shekhinah as a feminine aspect of Yahweh, may be a cultural memory or devolution of Asherah.

- Jenny Kein, (2000)”Reinstating the Divine Woman in Judaism” (Universal Publishers; 1 edition (January 15, 2000)

- Bach, Alice Women in the Hebrew Bible Routledge; 1 edition (3 Nov 1998) ISBN 978-0-415-91561-8 p.171

- Donald B. Redford, Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times, Princeton University Press, 1992 p.270.

In Christian scripture, the Holy Spirit is represented by a dove—a ubiquitous symbol of goddess religions, also found on Hebrew naos shrines. This speculation is not widely accepted. Goddess symbology nevertheless persists in Christian iconography; Israel Morrow notes that while Christian art typically displays female angels with avian wings, the only biblical reference to such figures comes through Zechariah‘s vision of pagan goddesses.

- Dever 2005

- Morrow, Israel (2019). Gods of the Flesh: A Skeptic’s Journey Through Sex, Politics and Religion. ISBN 9780578438290

Ugaritic amulets show a miniature “tree of life” growing out of Asherah’s belly. Accordingly, Asherah poles, which were sacred trees or poles, are mentioned many times in the Hebrew Bible, rendered as palus sacer (sacred poles) in the Latin Vulgate. Asherah poles were prohibited by the Deuteronomic Code that commanded “You shall not plant any tree as an Asherah beside the altar of the Lord your God”.

The prohibition, as Dever notes, is also a testament to the practice of putting up Asherah poles beside Yahweh’s altars (cf. 2 Kings 21:7) amongst Israelites. Another significant biblical reference occurs in the legend of Deborah, a female ruler of Israel who held court under a sacred tree (Book of Judges 4:5), which was preserved for many generations. Morrow further notes that the “funeral pillars of the kings” described by the Book of Ezekiel (43:9, variously translated as “funeral offerings” or even “carcasses of the kings”) were likely constructed of sacred wood, since the prophet connects them with “prostitution.”

- Dever 2005

- Morrow, Israel (2019). Gods of the Flesh: A Skeptic’s Journey Through Sex, Politics and Religion. ISBN 9780578438290

The lioness made a ubiquitous symbol for goddesses of the ancient Middle East that was similar to the dove and the tree. Lionesses figure prominently in Asherah’s iconography, including the tenth century BC Ta’anach cult stand, which also includes the tree motif. A Hebrew arrowhead from eleventh century BC bears the inscription “Servant of the Lion Lady”.

In Arabia

As ʾAṯirat (Qatabanian: 𐩱𐩻𐩧𐩩 ʾṯrt) she was attested in pre-Islamic south Arabia as the consort of the moon-god ʿAmm.

- Jordan, Michael (14 May 2014). Dictionary of Gods and Goddesses. Infobase Publishing. p. 37. ISBN 9781438109855.

One of the Tema stones (CIS II 113) discovered by Charles Huber in 1883 in the ancient oasis of Tema, northwestern Arabia, and now located at the Louvre, believed to date to the time of Nabonidus‘s retirement there in 549 BC, bears an inscription in Aramaic that mentions Ṣelem of Maḥram (צלם זי מחרמ), Šingalāʾ (שנגלא), and ʾAšîrāʾ (אשירא) as the deities of Tema. This ʾAšîrāʾ may be Asherah. It is unclear whether the name would be an Aramaic vocalisation of the Ugaritic ʾAṯirat or a later borrowing of the Hebrew ʾĂšērāh or similar form. In any event, the root of both names is a Proto-Semitic *ʾṯrt.

- Watkins, Justin (2007). “Athirat: As Found at Ras Shamra”. Studia Antiqua. 5 (1): 45–55. Archived from the original on 1 July 2019. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

The Arabic root ʾṯr (as in أثر ʾaṯar’,’ “trace”) is similar in meaning to the Hebrew ʾāšar, indicating “to tread”, used as a basis to explain Asherah’s epithet “of the sea” as “she who treads the sea” (especially as the Arabic root يم yamm also means “sea”).

Lucy Goodison and Christine E. Morris, Ancient Goddesses: Myths and Evidence (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1998), 79.

Recently, it has been suggested that the goddess name Athirat might be derived from the passive participle form, referring to “one followed by (the gods)”, that is, “pro-genitress or originatress”, corresponding with Asherah’s image as the “mother of the gods” in Ugaritic literature.

- Sung Jin Park, “Short Notes on the Etymology of Asherah”, Ugarit Forschungen 42 (2010): 527–534.

Asherah pole

An Asherah pole is a sacred tree or pole that stood near Canaanite religious locations to honor the Ugaritic mother goddess Asherah, consort of Ba’al. The relation of the literary references to an asherah and archaeological finds of Judaean pillar-figurines has engendered a literature of debate.

- Sarah Iles Johnston, ed. Religions of the Ancient World, (Belnap Press, Harvard) 2004, p. 418; a book-length scholarly treatment is W.L. Reed, The Asherah in the Old Testament (Fort Worth: Texas Christian University Press) 1949; the connection of the pillar figurines with Asherah was made by Raphael Patai in The Hebrew Goddess (1967)

- Summarized and sharply criticized in Raz Kletter’s The Judean Pillar-Figurines and the Archaeology of Asherah (Oxford: Tempus Reparatum), 1996; Kletter gives a catalogue of material remains.

The asherim were also cult objects related to the worship of Asherah, the consort of either Ba’al or, as inscriptions from Kuntillet ‘Ajrud and Khirbet el-Qom attest, Yahweh, and thus objects of contention among competing cults. In translations of the Hebrew Bible that render the Hebrew asherim (אֲשֵׁרִים ’ăšērīm) or asheroth (אֲשֵׁרוֹת ’ăšērōṯ) into English as “Asherah poles”, the insertion of “pole” begs the question by setting up unwarranted expectations for such a wooden object: “we are never told exactly what it was”, observes John Day. The traditional interpretation of the Biblical text is that the Israelites imported pagan elements such as the Asherah poles from the surrounding Canaanites. In light of archeological finds, however, some modern scholars now theorize that the Israelite folk religion was Canaanite in its inception and always polytheistic; this theory holds that the innovators were the prophets and priests who denounced the Asherah poles. Such theories inspire ongoing debate.

- W.G. Dever, “Asherah, Consort of Yahweh? New Evidence from Kuntillet ʿAjrûd” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research,1984; D.N. Freedman, “Yahweh of Samaria and his Asherah”, The Biblical Archaeologist, 1987; Morton Smith, “God Male and Female in the Old Testament: Yahweh and his Asherah” Theological Studies, 1987; J.M. Hadley “The Khirbet el-Qom Inscription”, Vetus Testamentum, 1987

- Day 1986, pp. 401–04.

- William G. Dever, Did God have a Wife?: Archaeology and Folk Religion in Ancient Israel, 2005

- Shmuel Ahituv (2006), Did God have a Wife?, Biblical Archaeology Review, Book Review

References from the Hebrew Bible

Asherim are mentioned in the Hebrew Bible in the books of Exodus, Deuteronomy, Judges, the Books of Kings, the second Book of Chronicles, and the books of Isaiah, Jeremiah, and Micah. The term often appears as merely אשרה, (Asherah) referred to as “groves” in the King James Version, which follows the Septuagint rendering as ἄλσος, pl. ἄλση and the Vulgate lucus, and “poles” in the New Revised Standard Version; no word that may be translated as “poles” appears in the text. Scholars have indicated, however, that the plural use of the term (English “Asherahs”, translating Hebrew Asherim or Asherot) provides ample evidence that reference is being made to objects of worship rather than a transcendent figure.

- Day 1986, p. 401.

- van der Toorn, Becking, van der Horst (1999), Dictionary of Deities and Demons in The Bible, Second Extensively Revised Edition, pp. 99-105, William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, ISBN 0-8028-2491-9

The Hebrew Bible suggests that the poles were made of wood. In the sixth chapter of the Book of Judges, God is recorded as instructing the Israelite judge Gideon to cut down an Asherah pole that was next to an altar to Baal. The wood was to be used for a burnt offering.

Deuteronomy 16:21 states that YHWH (rendered as “the Lord”) hated Asherim whether rendered as poles: “Do not set up any [wooden] Asherah [pole] beside the altar you build to the Lord your God” or as living trees: “You shall not plant any tree as an Asherah beside the altar of the Lord your God which you shall make”. That Asherahs were not always living trees is shown in 1 Kings 14:23: “their asherim, beside every luxuriant tree”. However, the record indicates that the Jewish people often departed from this ideal. For example, King Manasseh placed an Asherah pole in the Holy Temple (2 Kings 21:7). King Josiah’s reforms in the late 7th century BC included the destruction of many Asherah poles (2 Kings 23:14).

- Wooden and pole are translators’ interpolations in the text, which makes no such characterization of Asherah.

- Various translations of Deuteronomy 16.21 compared.

- Day 1986, p. 402 – “Which would be odd if the Asherim were themselves trees”, noting that there is general agreement that the asherim were man-made objects

Exodus 34:13 states: “Break down their altars, smash their sacred stones and cut down their Asherim [Asherah poles].”

Asherah poles in biblical archaeology

Some biblical archaeologists have suggested that until the 6th century BC the Israelite peoples had household shrines, or at least figurines, of Asherah, which are strikingly common in the archaeological remains.

- Finkelstein, Israel; Silberman, Neil Asher (2002). The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology’s New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Sacred Texts. Simon and Schuster. pp. 242, 288. ISBN 978-0-7432-2338-6.

Raphael Patai identified the pillar figurines with Asherah in The Hebrew Goddess.

- Thompson, Thomas L.; Jayyusi, Salma Khadra, eds. (2003). Jerusalem in ancient history and tradition: Conference in Jordan on 12 – 14 October 2001 (Volume 381 of Journal for the Study of the Old Testament: Supplement Series, Illustrated). London: T & T Clark. p. 139. ISBN 978-0-567-08360-9.

See also

- Baetylus, type of sacred standing stone

- High place, raised place of worship

- Ceremonial pole

- Sacred trees and groves in Germanic paganism and mythology

- Matzevah, sacred pillar (Hebrew Bible) or Jewish headstone

- Menhir, orthostat, or standing stone: upright stone, typically from the Bronze Age

- Stele, stone or wooden slab erected as a monument

- Trees in mythology

- Maqam

- Boaz and Jachin

- 214 Aschera

- Al-Lat

- Anat

- Khirbet el-Qom

- Kuntillet ʿAjrud

- List of fertility deities

- List of Canaanite deities

- Nehushtan

- Queen of Heaven (antiquity)

- Semitic neopaganism

- Shekhinah

- Ugarit

Explanatory notes

- [a] Hebrew: מְלֶכֶת הַשָּׁמַיִם

- [b] Ugaritic 𐎗𐎁𐎚 𐎀𐎘𐎗𐎚 𐎊𐎎, rbt ʾṯrt ym

- [c] Ugaritic 𐎖𐎐𐎊𐎚 𐎛𐎍𐎎, qnyt ʾlm

- [d] Ugaritic 𐎛𐎍𐎚, ʾilt

- [e] Ugaritic 𐎖𐎄𐎌, qdš

Citations

- Rahmouni, Aïcha (2008). Divine Epithets in the Ugaritic Alphabetic Texts. Translated by Ford, J. N. Leiden: Brill. p. 285. ISBN 978-9004157699.

Margalit (1980) […] consistently translates rbt ʾaṯrt ym as ‘Lady-Asherah of the Sea’, similar to the translation proposed in the present study, but his reference to ‘Asherah, Great-Lady-of the-Sea’ […] is surely incorrect. An epithet *ʾaṯrt rbt ym is unattested and there is no basis for translating rbt ʾaṯrt ym in such a manner.

- Miller, Patrick D. (1967). “El the Warrior”. The Harvard Theological Review. 60 (4): 411–431. doi:10.1017/S0017816000003886. JSTOR 1509250. S2CID 162038758.

- “Asherah”. The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia. Columbia University Press. 2022. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- Day, John. “Asherah in the Hebrew Bible and Northwest Semitic Literature.” Journal of Biblical Literature, vol. 105, no. 3, 1986, pp. 385–408. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3260509. Accessed 5 Aug. 2021.

- “DASI: Digital Archive for the Study of pre-islamic arabian Inscriptions: Word list occurrences”. dasi.cnr.it. Archived from the original on 6 August 2021. Retrieved 6 August 2021.

- ‘Asertu, tablet concordance KUB XXXVI 35 – CTH 342 Archived 5 August 2021 at the Wayback Machine‘, Hittite Collection, Hatice Gonnet-Bağana; Koç University.

- “Asherah” in The New Encyclopædia Britannica. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 15th edn., 1992, Vol. 1, pp. 623–624.

- Leeming, David (17 November 2005). The Oxford Companion to World Mythology. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-19-515669-0. Archived from the original on 26 February 2022. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- Binger, Tilde (1997). Asherah: Goddesses in Ugarit, Israel and the Old Testament (1st ed.). Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press. pp. 74. ISBN 9780567119766.

- Deuteronomy 12: 3–4

- Olyan, Saul M. (1988), Asherah and the cult of Yahweh in Israel, Scholars Press, p. 79, ISBN 9781555402549

- “…pray thou not for this people… The children gather wood, and the fathers kindle the fire, and the women knead [their] dough, to make cakes to the queen of heaven, and to pour out drink offerings to other gods, that they may provoke me to anger.” (King James Version)

- Rainer, Albertz (2010), “Personal piety”, in Stavrakopoulou, Francesca; Barton, John (eds.), Religious Diversity in Ancient Israel and Judah (reprint ed.), Continuum International Publishing Group, pp. 135–146 (at 143), ISBN 9780567032164

- Gibson, J. C. L.; Driver, G. R. (1978), Canaanite Myths and Legends, T. & T. Clark, ISBN 9780567023513

- Wiggins, Steve A. (2007). Wyatt, N. (ed.). A Reassessment of Asherah: With Further Considerations of the Goddess. Gorgias Ugaritic Studies 2. NJ, USA: Gorgias Press. p. 77.

- Ahlström, Gösta W. (1963). Engnell, Ivan; Furumark, Arne; Nordström, Carl-Otto (eds.). Aspects of Syncretism in Israelite Religion. Horae Soederblominae 5. Translated by Sharpe, Eric J. Lund, SE: C.W.K. Gleerup. p. 68.

- Rahmouni, Aicha (2008). “Epithet 94: rbt ʾaṯrt ym”. Divine Epithets in the Ugaritic Alphabetic Texts. Translated by Ford, J. N. Leiden, NE: Brill. pp. 278. ISBN 9789004157699.

- Rahmouni, Aicha (2008). “Epithet 94: rbt ʾaṯrt ym”. Divine Epithets in the Ugaritic Alphabetic Texts. Translated by Ford, J. N. Leiden, NE: Brill. pp. 281. ISBN 9789004157699.

- Binger, Tilde (1997). Asherah: Goddesses in Ugarit, Israel and the Old Testament (1st ed.). Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press. pp. 44. ISBN 9780567119766.

- Wyatt, N. (2003). Religious Texts from Ugarit (2nd ed.). London: Sheffield Academic Press. pp. 131 et al.

- Sung Jin Park, “Short Notes on the Etymology of Asherah”, Ugarit Forschungen 42 (2010): 527–534.

- Albright, W. F. (1968). Yahweh and the gods of Canaan: a historical analysis of two contrasting faiths. London: University of London, Athlone Press. pp. 105–106. ISBN 9780931464010.

- Emerton, J. A. (1982). “New Light on Israelite Religion: The Implications of the Inscriptions from Kuntillet ʿAjrud”, Zeitschrift für die Alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 94. Brill. p. 8. doi:10.1515/zatw.1982.94.1.2. S2CID 170614720.

- Binger, Tilde (1997). Asherah: Goddesses in Ugarit, Israel and the Old Testament (1st ed.). Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press. pp. 42–93. ISBN 9780567119766.

- Kogan, Leonid (2012). “Proto-Semitic Lexicon”. In Weninger, Stefan (ed.). The Semitic Languages: An International Handbook. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 179–258.

- Numbers 6:5, Job 7:6

- see KTU 1.4 I 23.

- Noted by Raphael Patai, “The Goddess Asherah”, Journal of Near Eastern Studies 24.1/2 (1965: 37–52), p. 39.

- Hess, Richard S. “Asherah or Asherata?” Orientalia, vol. 65, no. 3, 1996, pp. 209–219. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/43078131. Accessed 6 Aug. 2021.

- The Ugaritic Baal cycle: Volume 2 by Mark S. Smith, page 295

- The Origins of Biblical Monotheism: Israel’s Polytheistic Background and the Ugaritic Texts by Mark S. Smith – Page 237

- Finkelstein, Israel, and Silberman, Neil Asher, The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology’s New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts, Simon & Schuster, 2002, pp. 241–242.

- “BBC Two – Bible’s Buried Secrets, Did God Have a Wife?”. BBC. 21 December 2011. Archived from the original on 15 January 2012. Retrieved 4 July 2012.

- Quote from the BBC documentary (prof. Herbert Niehr): “Between the 10th century and the beginning of their exile in 586 there was polytheism as normal religion all throughout Israel; only afterwards things begin to change and very slowly they begin to change. I would say it [the sentence “Jews were monotheists” – n.n.] is only correct for the last centuries, maybe only from the period of the Maccabees, that means the second century BC, so in the time of Jesus of Nazareth it is true, but for the time before it, it is not true.”

- Wesler, Kit W. (2012). An Archaeology of Religion. University Press of America. p. 193. ISBN 978-0761858454. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 3 September 2014.

- Mills, Watson, ed. (31 December 1999). Mercer Dictionary of the Bible (Reprint ed.). Mercer University Press. p. 494. ISBN 978-0865543737. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 5 November 2020.

- “Genesis Chapter 1 (NKJV)”. Blue Letter Bible. Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- Ze’ev Meshel, Kuntillet ‘Ajrud: An Israelite Religious Center in Northern Sinai Archived 29 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Expedition 20 (Summer 1978), pp. 50–55

- Dever 2005

- Hadley 2000, pp. 122–136

- Bonanno, Anthony (1986). Archaeology and Fertility Cult in the Ancient Mediterranean: Papers Presented at the First International Conference on Archaeology of the Ancient Mediterranean, University of Malta, 2–5 September 1985. John Benjamins Publishing. p. 238. ISBN 9789060322888. Archived from the original on 18 January 2022. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Keel, Othmar; Uehlinger, Christoph (1998). Gods, Goddesses, And Images of God. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 228. ISBN 9780567085917. Archived from the original on 15 June 2021. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Keel, Othmar; Uehlinger, Christoph (1998). Gods, Goddesses, And Images of God. Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 232–233. ISBN 9780567085917. Archived from the original on 15 June 2021. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Sung Jin Park, “The Cultic Identity of Asherah in Deuteronomistic Ideology of Israel,” Zeitschrift für die Alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 123/4 (2011): 553–564.

- Ackerman, Susan (1993). “The Queen Mother and the Cult in Ancient Israel”. Journal of Biblical Literature. 112 (3): 385–401. doi:10.2307/3267740. JSTOR 3267740.

- Bowen, Nancy (2001). “The Quest for the Historical Gĕbîrâ”. Catholic Biblical Quarterly. 64: 597–618.

- 1 Kings 15:13; 18:19, 2 Kings 10:13

- Dever 2005, p. 163.

- “Asherah”. www.asphodel-long.com. Archived from the original on 5 January 2006. Retrieved 14 February 2016.

- Danby, Herbert (1933). The Mishnah: Translated from the Hebrew With Introduction and Brief Explanatory Notes. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 90, 176. ISBN 9780198154020.

- Coogan, Michael (2010). God and Sex. Twelve. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-446-54525-9.

- Stone, Merlin (1976). When God Was A Woman: The landmark exploration of the ancient worship of the Great Goddess and the eventual suppression of women’s rites. ISBN 015696158X.

- Coogan 2010, p. 133.

- Jenny Kein, (2000)”Reinstating the Divine Woman in Judaism” (Universal Publishers; 1 edition (January 15, 2000)

- Bach, Alice Women in the Hebrew Bible Routledge; 1 edition (3 Nov 1998) ISBN 978-0-415-91561-8 p.171

- Donald B. Redford, Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times, Princeton University Press, 1992 p.270.

- Morrow, Israel (2019). Gods of the Flesh: A Skeptic’s Journey Through Sex, Politics and Religion. ISBN 9780578438290.

- Deut 16:21

- Jordan, Michael (14 May 2014). Dictionary of Gods and Goddesses. Infobase Publishing. p. 37. ISBN 9781438109855.

- Watkins, Justin (2007). “Athirat: As Found at Ras Shamra”. Studia Antiqua. 5 (1): 45–55. Archived from the original on 1 July 2019. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- Lucy Goodison and Christine E. Morris, Ancient Goddesses: Myths and Evidence (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1998), 79.

- Sarah Iles Johnston, ed. Religions of the Ancient World, (Belnap Press, Harvard) 2004, p. 418; a book-length scholarly treatment is W.L. Reed, The Asherah in the Old Testament (Fort Worth: Texas Christian University Press) 1949; the connection of the pillar figurines with Asherah was made by Raphael Patai in The Hebrew Goddess (1967)

- Summarized and sharply criticized in Raz Kletter’s The Judean Pillar-Figurines and the Archaeology of Asherah (Oxford: Tempus Reparatum), 1996; Kletter gives a catalogue of material remains.

- W.G. Dever, “Asherah, Consort of Yahweh? New Evidence from Kuntillet ʿAjrûd” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research,1984; D.N. Freedman, “Yahweh of Samaria and his Asherah”, The Biblical Archaeologist, 1987; Morton Smith, “God Male and Female in the Old Testament: Yahweh and his Asherah” Theological Studies, 1987; J.M. Hadley “The Khirbet el-Qom Inscription”, Vetus Testamentum, 1987

- Day 1986, pp. 401–04.

- William G. Dever, Did God have a Wife?: Archaeology and Folk Religion in Ancient Israel, 2005

- Shmuel Ahituv (2006), Did God have a Wife?, Biblical Archaeology Review, Book Review

- Day 1986, p. 401.

- van der Toorn, Becking, van der Horst (1999), Dictionary of Deities and Demons in The Bible, Second Extensively Revised Edition, pp. 99-105, William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, ISBN 0-8028-2491-9

- Wooden and pole are translators’ interpolations in the text, which makes no such characterization of Asherah.

- Various translations of Deuteronomy 16.21 compared.

- Day 1986, p. 402 – “Which would be odd if the Asherim were themselves trees”, noting that there is general agreement that the asherim were man-made objects

- Finkelstein, Israel; Silberman, Neil Asher (2002). The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology’s New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Sacred Texts. Simon and Schuster. pp. 242, 288. ISBN 978-0-7432-2338-6.

- Thompson, Thomas L.; Jayyusi, Salma Khadra, eds. (2003). Jerusalem in ancient history and tradition: Conference in Jordan on 12 – 14 October 2001 (Volume 381 of Journal for the Study of the Old Testament: Supplement Series, Illustrated). London: T & T Clark. p. 139. ISBN 978-0-567-08360-9.

General sources

- Ahlström, Gösta W. (1963), Engnell, Ivan; Furumark, Arne; Nordström, Carl-Otto (eds.), Aspects of Syncretism in Israelite Religion, Horae Soederblominae 5, translated by Sharpe, Eric J., Lund, SE: C.W.K. Gleerup, p. 68

- Albright, W. F. (1968), Yahweh and the gods of Canaan: a historical analysis of two contrasting faiths, London: University of London, Athlone Press, pp. 105–106, ISBN 9780931464010

- Barker, Margaret (2012), The Mother of the Lord Volume 1: The Lady in the Temple, T & T Clark, ISBN 9780567528155

- Binger, Tilde (1997), Asherah: Goddesses in Ugarit, Israel and the Old Testament (1st ed.), Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, pp. 42–93, ISBN 9780567119766

- Day, John (September 1986). “Asherah in the Hebrew Bible and Northwest Semitic Literature”. Journal of Biblical Literature. 105 (3): 385–408. doi:10.2307/3260509. JSTOR 3260509.

- Dever, William G. (2005), Did God Have A Wife?: Archaeology And Folk Religion In Ancient Israel, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, ISBN 9780802828521

- Emerton, J. A. (1982). “New Light on Israelite Religion: The Implications of the Inscriptions from Kuntillet ʿAjrud”. Zeitschrift für die Alttestamentliche Wissenschaft. 94: 2–20. doi:10.1515/zatw.1982.94.1.2. S2CID 170614720.

- Hadley, Judith M. (2000), The Cult of Asherah in Ancient Israel and Judah: The Evidence for a Hebrew Goddess, University of Cambridge Oriental publications, 57, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9780521662352

- Kien, Jenny (2000), Reinstating the Divine Woman in Judaism, Universal Publishers, ISBN 9781581127638, OCLC 45500083

- Long, Asphodel P. (1993), In a Chariot Drawn by Lions: The Search for the Female in Deity, Crossing Press, ISBN 9780895945754.

- Myer, Allen C. (2000), “Asherah”, Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible, Amsterdam University Press

- Park, Sung Jin (2010). “Short Notes on the Etymology of Asherah”. Ugarit Forschungen. 42: 527–534.

- Park, Sung Jin (2011). “The Cultic Identity of Asherah in Deuteronomistic Ideology of Israel”. Zeitschrift für die Alttestamentliche Wissenschaft. 123 (4): 553–564. doi:10.1515/zaw.2011.036. S2CID 170589596.

- Patai, Raphael (1990), The Hebrew Goddess, Jewish folklore and anthropology, Wayne State University Press, ISBN 9780814322710, OCLC 20692501.

- Rahmouni, Aicha (2008), Divine Epithets in the Ugaritic Alphabetic Texts, translated by Ford, J. N., Leiden, NE: Brill

- Reed, William Laforest (1949), The Asherah in the Old Testament, Texas Christian University Press, OCLC 491761457.

- Taylor, Joan E. (1995), “The Asherah, the Menorah and the Sacred Tree”, Journal for the Study of the Old Testament, University of Sheffield, Dept. of Biblical Studies, 20 (66): 29–54, doi:10.1177/030908929502006602, ISSN 0309-0892, OCLC 88542166, S2CID 170422840

- Wiggins, Steve A. (1993), A Reassessment of ‘Asherah’: A Study according to the Textual Sources of the First Two Millennia B.C.E, Alter Orient und Altes Testament, Bd. 235., Verlag Butzon & Bercker, ISBN 9783788714796

- Wiggins, Steve A. (2007), Wyatt, N. (ed.), A Reassessment of Asherah: With Further Considerations of the Goddess, Gorgias Ugaritic Studies 2 (2nd ed.), New Jersey: Gorgias Press

- Wyatt, N. (2003), Religious Texts from Ugarit (2nd ed.), London: Sheffield Academic Press

External links

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Asherah.

Asherah

- Asphodel P. Long, The Goddess in Judaism – An Historical Perspective

- Asherah, the Tree of Life and the Menorah

- Jewish Encyclopedia: Asherah

- Rabbi Jill Hammer, An Altar of Earth: Reflections on Jews, Goddesses and the Zohar

- University of Birmingham: Deryn Guest: Asherah at Archive.org

- Lilinah biti-Anat, Qadash Kinahnu Deity Temple “Room One, Major Canaanite Deities”

Kuntillet ʿAjrud inscriptions

- Jacques Berlinerblau, “Official religion and popular religion in pre-Exilic ancient Israel” (Commentary on Yahweh’s Asherah.)

- ANE: Kuntillet bibliography

- Jeffrey H. Tigay, “A Second Temple Parallel to the Blessings from Kuntillet Ajrud” (University of Pennsylvania) (This equates Asherah with an asherah.)

Israelite

- Ancient Israel and Judah

- Hebrew Bible objects

- Levantine mythology

- Religious objects

- Trees in religion

- Book of Exodus

- Book of Deuteronomy

- Book of Judges

- Books of Kings

- Books of Chronicles

- Book of Isaiah

- Book of Jeremiah

- Book of Micah

- Asherah

- Deities in the Hebrew Bible

- Fertility goddesses

- Mother goddesses

- Phoenician mythology

- West Semitic goddesses

- South Arabia

- Arabian goddesses

- Queens of Heaven (antiquity)

- Ugaritic deities

Leave a Reply